Microfilms International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Para Descargar En Formato

Fabio G. Nigra Secretaria de Redacción Valeria L. Carbone Comité Editorial Comité Académico Aimé Olguín (UBA) Bárbara Gudaitis (UBA) Argentina Darío Martini (UBA) Graciela Iuorno, Universidad Nacional del Comahue. Florencia Dadamo (UBA) Margara Averbach. Facultad Filosofía y Letras. Gabriel Matelo (UNLP) Universidad de Buenos Aires Leandro Della Mora (UBA) María Graciela Abarca, Universidad de Buenos Aires / Leandro Morgenfeld (UBA) Universidad del Salvador Leonardo Pataccini (Univ of Tartu) Pablo Pozzi, Facultad Filosofía y Letras. Universidad de Malena López Palmero (UBA) Buenos Aires Mariana Mastrángelo (UndeC) Mariana Piccinelli (UBA) Martha de Cunto (UBA) Brasil Valeria L. Carbone (UBA) Alexandre Busko Valim, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Francisco César Alvez Ferraz, Universidade Estadual do Colaboradores Secretaría de Londrina Redacción Marcos Fábio Freire Montysuma, Universidade Federal Federico Sena de Santa Catarina Robson Laverdi, Universidade Estadual do Ponta Grossa Joaquina De Donato Sidnei J. Munhoz, Universidade Estadual do Maringá Sebastián Diz Cuba Jorge Hernández Martínez, Universidad de La Habana Estados Unidos de América Marc Stern, Bentley University Michael Hannahan, University of Massachusetts “Una nueva hegemonía” España #15 / Oct 2018 Carmen Manuel, Universidad de Valencia huellasdeeua.com.ar ISSN 1853-6506 Perú Norberto Barreto, Universidad del Pacífico en Lima TABLA DE CONTENIDOS 10. Andrés Sebastián Diz Religión y política en los Estados Unidos de América.............................. 129 11. Atiba Rogers Después de dos décadas, autor Editorial Fabio G. Nigra | “A diez años de la jamaiquino finalmente desvela libro dedicado a crisis de los créditos subprime” .............................. 2 Marcus Garvey ............................................................ 136 1. Alexandre Guilherme da Cruz Alves Junior American Freedom on Trial: The First Amendment Battle Between the Pornography Industry and Christian Fundamentalism ............ -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

David S. Ware in Profile

Steve Coleman: The Most Influential Figure Since Coltrane? AMERICA’s JAZZ MAGAZINE Win a Trip for Two on The Jazz Cruise! TBetweenia Fuller Bop&Beyoncé David S. Ware Fred Ho in Profile His Harrowing BY DAVID R. ADLER Fight Against Cancer Before & After Lee Konitz Nate Chinen on Kirk Whalum John Ellis A $250,000 Turntable? Audiophile Gear to Die For Stan Getz & Kenny Barron Reviewed 40 JAZZTIMES >> JUNE 2010 A f te r the here were torrential rains, and gusts up to 60 miles per hour, on the night in mid- March when saxophone icon David S. Ware played solo before an intimate crowd in Brooklyn. Seated in the cozy home office of host Garrett Shelton, a music industry con- sultant, Ware began with an assertive, envel- Still coping with the oping improvisation on sopranino—a new Thorn in his arsenal—and followed it with an S toaftermath of a rkidney m extended tenor display, rigorously developed, with mounting sonic power. transplant, David S. Ware After he finished, Ware played up the salon-like atmosphere by inviting questions forges ahead with solo from listeners. Multi-instrumentalist Cooper- Moore, Ware’s good friend and one-time saxophone, a new trio roommate, who (like me) nearly missed the show on account of a subway power outage, and a return to the Vision was among the first to speak. He noted that the weather was also perfectly miserable on Festival this summer Oct. 15, 2009, the night of Ware’s previous solo concert. So one had to wonder, “What’s goin’ on with you, man?” Laughing, Ware By David R. -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

1457054074479.Pdf

Dead/ands'" Dime Novel'" #4 lXDER;A- ++-~O/ED f'..'ool (P,4-1<f O tE): .slK:.P!~ BEDFFI I Oil5=- Written by: Matt Forbeck Production: Barry Doyle & Hal Mangold Cover Art and Logo: Ron Spencer Interior Art: Kevin Sharpe Maps: Jeff Lahren Special Thanks to: Justin /\chilli. Kelley Foote, Shane & Michelle Hensley. John Hopler, Ann Kolinsky. Ashe Marler. Dave seay. Ethan Skemp. Richard Thomas, Matt Tice. Mike TInney. Stephen Wieck, John Zinser. Dead/ands created by Shane Lacy Hensley werewo!f:The Wild West created by Justin Achilli &Ethan Skemp PINNACLE ENTERTAINMENT GROUP, Inc. elM! STUDIO .. ~." "Iito-" "t< • 'lito'''' ~-. lito-.· Pinnade Entertainment Group, Inc. P.O. Box 10908 Blacksburg. VA 24062-()908 www.peginc.comordeadlandSiiaol.com (BOO) 214-5645 (orders only) DeadIandJ. Dime -.. WciId WesI..he DaclIIrIds Iogo..r>d the P"",ack SUrtlunl If\! Tl"IIdema,'u <If Plnnaele Enteruolnmenl Gmup. In<. ~ The WlId west is. Trademarl< d WMc WOlf. Inc. The White 'M;>If GP'Ie S1udoo lot<> is. R"IIkSI~ Tr.aoern.rt 0( Whole WOlf. inc. C 1997 Pinnae" Enlt!flllnlMrll Group. Inc.. Ind While WOlf. InC. ~!I Rights R<'5tfW:d. _Icd In ,he USA .?~ t;EDt-E.LONS There was something different about this camp, though. The larger tents bore the brassy emblems of Wasatch, the company controlled by Dr. Darius Hellstromme, the most notorious master of steam technology the West had to offer. That wasn't why Ronan was here though-at least not directly. Wasatch was laying dozens of spurs off of their main line on their way toward the coast. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

DB Music Shop Must Arrive 2 Months Prior to DB Cover Date

05 5 $4.99 DownBeat.com 09281 01493 0 MAY 2010MAY U.K. £3.50 001_COVER.qxd 3/16/10 2:08 PM Page 1 DOWNBEAT MIGUEL ZENÓN // RAMSEY LEWIS & KIRK WHALUM // EVAN PARKER // SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE MAY 2010 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:28 AM Page 2 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 3 002-025_FRONT.qxd 3/17/10 10:29 AM Page 4 May 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

2008 OAH Annual Meeting • New York 1

Welcome ear colleagues in history, welcome to the one-hundred-fi rst annual meeting of the Organiza- tion of American Historians in New York. Last year we met in our founding site of Minneap- Dolis-St. Paul, before that in the national capital of Washington, DC. On the present occasion wew meet in the world’s media capital, but in a very special way: this is a bridge-and-tunnel aff air, not limitedli to just the island of Manhattan. Bridges and tunnels connect the island to the larger metropolitan region. For a long time, the peoplep in Manhattan looked down on people from New Jersey and the “outer boroughs”— Brooklyn, theth Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island—who came to the island via those bridges and tunnels. Bridge- and-tunnela people were supposed to lack the sophistication and style of Manhattan people. Bridge- and-tunnela people also did the work: hard work, essential work, beautifully creative work. You will sees this work in sessions and tours extending beyond midtown Manhattan. Be sure not to miss, for example,e “From Mambo to Hip-Hop: Th e South Bronx Latin Music Tour” and the bus tour to my own Photo by Steve Miller Steve by Photo cityc of Newark, New Jersey. Not that this meeting is bridge-and-tunnel only. Th anks to the excellent, hard working program committee, chaired by Debo- rah Gray White, and the local arrangements committee, chaired by Mark Naison and Irma Watkins-Owens, you can chose from an abundance of off erings in and on historic Manhattan: in Harlem, the Cooper Union, Chinatown, the Center for Jewish History, the Brooklyn Historical Society, the New-York Historical Society, the American Folk Art Museum, and many other sites of great interest. -

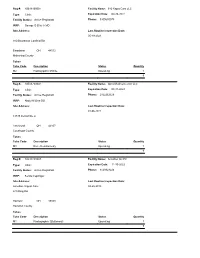

George G Ellis Jr MD IRRP: Site Address: 910 Boardman Canfield

Reg #: 10B18165001 Facility Name: 910 Rapid Care LLC Type: Clinic Expiration Date: 09-30-2022 Facility Status: Active Registrant Phone: 3309650075 IRRP: George G Ellis Jr MD Site Address: Last Routine Inspection Date: 05-19-2021 910 Boardman Canfield Rd Boardman OH 44512 Mahoning County Tubes Tube Code Description Status Quantity M2 Radiographic Mobile Operating 1 1 Reg #: 10E05750001 Facility Name: Abco Medical Center LLC Type: Clinic Expiration Date: 03-31-2023 Facility Status: Active Registrant Phone: 2162262626 IRRP: Abdul M Orra DO Site Address: Last Routine Inspection Date: 01-06-2021 13535 Detroit Ste 4 Lakewood OH 44107 Cuyahoga County Tubes Tube Code Description Status Quantity M3 Bone Densitometry Operating 1 1 Reg #: 10C18191001 Facility Name: AccuDoc Inc PC Type: Clinic Expiration Date: 11-30-2022 Facility Status: Active Registrant Phone: 8129323224 IRRP: Kenda Caplinger Site Address: Last Routine Inspection Date: AccuDoc Urgent Care 04-25-2018 620 Ring Rd Harrison OH 45030 Hamilton County Tubes Tube Code Description Status Quantity M1 Radiographic (Stationary) Operating 1 1 Reg #: 10G17042001 Facility Name: Action Spine and Pain Center PC Type: Clinic Expiration Date: 07-31-2023 Facility Status: Active Registrant Phone: 3306661400 IRRP: Dhruv J Shah MD Site Address: Last Routine Inspection Date: 06-06-2018 57 Baker Blvd Akron OH 44333 Summit County Tubes Tube Code Description Status Quantity M9 Fluoroscopic: C-Arm (Stationary) Operating 1 1 Reg #: 10B20325001 Facility Name: Active Life Health of Columbus LLC Type: Clinic Expiration -

The Fight Master, Spring/Summer 2003, Vol. 26 Issue 1

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Fight Master Magazine The Society of American Fight Directors Summer 2003 The Fight Master, Spring/Summer 2003, Vol. 26 Issue 1 The Society of American Fight Directors Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight Part of the Acting Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons MMARTIALARTIALAARTSRTS ONON TTOUROUR BBARAR FFIGHTSIGHTS In Voice of the Dragon, Miao Hin (Philip Silvera, left) battles with his nemesis Red Phoenix Manchu Warrior (Bilqis Benu). Martial arts choreography and photo provided by Jose Manuel Figueroa. The 24th Annual Society of American Fight Directors National Stage Combat Workshops July 7-25, 2003 SAFD and University of Nevada-Las Vegas College of Fine Arts, Department of Theatre ForFor moremore information:information: LindaLinda McCollumMcCollum atat (702)(702) 895-3662895-3662 oror www.safd.orgwww.safd.org www.safd.org Actor/Combatant Workshop (ACW) Train in the foundation skills of stage combat. World-class industry professionals teach tech- niques in Rapier and Dagger, Unarmed and Broadsword. Additionally, participants will receive an introduction to Quarterstaff, film fighting, and other weapon styles. Participants may opt to take an adjudicated Skills Proficiency Test at the end of the workshop. Intermediate Actor/Combatant Workshop (IACW) Move past the basics in this exciting workshop. Study many weapon styles and other issues of fight performance for stage and film. Build onto your existing knowledge of stage combat under the tutelage of a wide array of world-class industry professionals. Participants may opt to take a combination of adjudicated Skills Proficiency Tests or Renewal Tests in up to six weapon forms at the workshop. -

Writing Our Hope Supp 1.Indd

wwritingriting oourur hhopeope a ’zine of creative nonfi ction by teenagers on themes of hope, tolerance and equality Supplement One Point Loma High School Writing Our Hope is a publication of Booker T. Washington Magnet High School in Montgomery, Alabama. Issues are produced in the Fall and Spring. For submission guidelines, visit www.writingourhope.org Only high school students may submit. © 2008 by the authors No work in Writing Our Hope may be reproduced without express written consent of the author and/or editor. For more information, contact: Foster Dickson Booker T. Washington Magnet High School 632. S Union Street, Montgomery, AL 36104 334-269-3617 [email protected] The Staff Faculty Adviser and Supplements Editor: Foster Dickson Student Staff for 2007-2008 (Issues #1 and #2): Editor: Madison Clark Assistant Editors: Rhiannon Johns and Rachel Lewis Contents Foster Dickson • Introduction 4 Farah Martinez • Where I’m From 6 Kyle Darcey • Ego Tripping 8 Carlos Juarez • Ego Tripping 9 Jose de la Luz • Mexico 10 Alejandra Rivera • Epilogue: My Future 12 Joshua Pandza • Ego Tripping 14 Ashley Moreno • An Autobiographical Incident 16 Juan Carlos Lopez • Ego Tripping 18 Winnie Riley • Ego Tripping 19 Daisy Luchega • Taken Away but Found 20 Jessica Massey • Ego Tripping: England 22 Derek Anderson • The Punk Lifestyle 24 Dorey Ontiveros • November 8, 2008 26 Jaimee Hoff • April 9, 2008 28 Jesus Juarez • My Grandma, My Best Friend 29 Marlene Lira • Beautiful Image 31 Erika Solano • Ego Tripping 32 Mariela Cueva • Gothic Romance 34