The Growth of Beaus! in the Treatment of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiricahuas Present a Verdant, Forested Island in a Sea of Desert

Rising steeply from the dry grasslands of southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, the Chiricahuas present a verdant, forested island in a sea of desert. Many species of trees, shrubs, and flowering herbs clothe steep canyon walls. Shady glens, alive with birds, are sheltered by rows of strange massive spires, turrets, and battlements in this fascinating wonderland of rocks. Story of the rocks-What geological forces created these striking and peculiar pinnacles and balanced rocks? Geolo- gists explain that millions of years ago volcanic activity was extensive throughout this region. A series of explosive eruptions, alternating with periods of inactivity, covered the area with layers of white-hot volcanic ash that welded into rock. Because the eruptions varied in magnitude, the deposits were of different thicknesses. Finally, the eruptions ceased, followed by movements in the earth's crust which slowly lifted and tilted great rock masses to form mountains. The stresses responsible for the movements caused a definite pattern of cracks. Along the vertical cracks and planes of horizontal weakness, ero- sion by weathering and running water began its persistent work. Cracks were widened to form fissures; and fissures grew to breaches. At the same time, under-cutting slowly took place. Gradually the lava masses were cut by millions of ero- sional channels into blocks of myriad sizes and shapes, to be further sculptured by the elements. Shallow canyons became deeper and more rugged as time passed. Weathered rock formed soil, which collected in pockets; and plants thus gained a foothold. Erosion is still going on slowly and persistently among the great pillared cliffs of the monument. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Fort Bowie U.S

National Park Service Fort Bowie U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Bowie National Historic Site The Chiricahua Apaches Introduction The origin of the name "Apache" probably stems from the Zuni "apachu". Apaches in fact referred to themselves with variants of "nde", simply meaning "the people". By 1850, Apache culture was a blend of influences from the peoples of the Great Plains, Great Basin, and the Southwest, particularly the Pueblos, and as time progressed—Spanish, Mexican, and the recently arriving American settler. The Apache Tribes Chiricahua speak an Athabaskan language, relating Geronimo was a member of the Bedonkohe, who them to tribes of western Canada. Migration from were closely related to the Chihenne (sometimes this region brought them to the southern plains by referred to as the Mimbres); famous leaders of the 1300, and into areas of the present-day American band included Mangas Coloradas and Victorio. Southwest and northwestern Mexico by 1500. This The Nehdni primarily dwelled in northern migration coincided with a northward thrust of Mexico under the leadership of Tuh. the Spanish into the Rio Grande and San Pedro Valleys. Cochise was a Chokonen Chiricahua leader who rose to leadership around 1856. The Chockonen Chiricahuas of southern Arizona and New primarily resided in the area of Apache Pass and Mexico were further subdivided into four bands: the Dragoon Mountains to the west. Bedonkohe, Chokonen, Chihenne, and Nehdni. Their total population ranged from 1,000 to 1,500 people. Organization and Apache population was thinly spread, scattered of Apache government and was the position that Family Life into small groups across large territories, tribal chiefs such as Cochise held. -

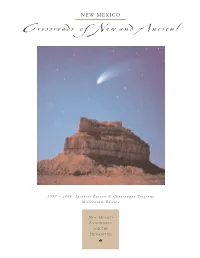

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Journal of Arizona History Index, M

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) M McAdams, Cliff, book by, reviewed 26:242 McAdoo, Ellen W. 43:225 McAdoo, W. C. 18:194 McAdoo, William 36:52; 39:225; 43:225 McAhren, Ben 19:353 McAlister, M. J. 26:430 McAllester, David E., book coedited by, reviewed 20:144-46 McAllester, David P., book coedited by, reviewed 45:120 McAllister, James P. 49:4-6 McAllister, R. Burnell 43:51 McAllister, R. S. 43:47 McAllister, S. W. 8:171 n. 2 McAlpine, Tom 10:190 McAndrew, John “Boots”, photo of 36:288 McAnich, Fred, book reviewed by 49:74-75 books reviewed by 43:95-97 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 McArtan, Neill, develops Pastime Park 31:20-22 death of 31:36-37 photo of 31:21 McArthur, Arthur 10:20 McArthur, Charles H. 21:171-72, 178; 33:277 photos 21:177, 180 McArthur, Douglas 38:278 McArthur, Lorraine (daughter), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Lorraine (mother), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Louise, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Perry 43:349 McArthur, Warren, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Warren, Jr. 33:276 article by and about 21:171-88 photos 21:174-75, 177, 180, 187 McAuley, (Mother Superior) Mary Catherine 39:264, 265, 285 McAuley, Skeet, book by, reviewed 31:438 McAuliffe, Helen W. -

Commencement1991.Pdf (8.927Mb)

TheJohns Hopkins University Conferring of Degrees At the Close of the 1 1 5th Academic Year MAY 23, 1991 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/commencement1991 Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Johns Hopkins Society of Scholars 10 Honorary Degree Citations 12 Academic Regalia 15 Awards 17 Honor Societies 21 Student Honors 23 Degree Candidates 25 As final action cannot always be taken by the time the program is printed, the lists of candidates, recipients of awards and prizes, and designees for honors are tentative only. The University reserves the right to withdraw or add names. Order ofProcession MARSHALS Sara Castro-Klaren Peter B. Petersen Eliot A. Cohen Martin R. Ramirez Bernard Guyer Trina Schroer Lynn Taylor Hebden Stella M. Shiber Franklin H. Herlong Dianne H. Tobin Jean Eichelberger Ivey James W. Wagner Joseph L. Katz Steven Yantis THE GRADUATES * MARSHALS Grace S. Brush Warner E. Love THE FACULTIES **- MARSHALS Lucien M. Brush, Jr. Stewart Hulse, Jr. THE DEANS MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY THE TRUSTEES CHDZF MARSHAL Noel R. Rose THE VICE PRESIDENT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNDTERSLTY ALUMNI ASSOCIATION THE CHAPLAINS THE PRESENTERS OF THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE INTERIM PROVOST OF THE UNIVERSITY THE CHADIMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNDTERSLTY 1 Order ofEvents William (.. Richardson President of the University, presiding * * « PRELUDE Suite from the American Brass Band Journal G.W.E. Friederich (1821-1885) Suite from Funff— stimmigte blasenda Music JohannPezel (1639-1694) » PROCESSIONAL The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing after the Invocation. -

The Cretaceous System in Central Sierra County, New Mexico

The Cretaceous System in central Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Albuquerque, NM 87104, [email protected] W. John Nelson, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, [email protected] Karl Krainer, Institute of Geology, Innsbruck University, Innsbruck, A-6020 Austria, [email protected] Scott D. Elrick, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, [email protected] Abstract (part of the Dakota Formation, Campana (Fig. 1). This is the most extensive outcrop Member of the Tres Hermanos Formation, area of Cretaceous rocks in southern New Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks are Flying Eagle Canyon Formation, Ash Canyon Mexico, and the exposed Cretaceous sec- Formation, and the entire McRae Group). A exposed in central Sierra County, southern tion is very thick, at about 2.5 km. First comprehensive understanding of the Cretaceous New Mexico, in the Fra Cristobal Mountains, recognized in 1860, these Cretaceous Caballo Mountains and in the topographically strata in Sierra County allows a more detailed inter- pretation of local geologic events in the context strata have been the subject of diverse, but low Cutter sag between the two ranges. The ~2.5 generally restricted, studies for more than km thick Cretaceous section is assigned to the of broad, transgressive-regressive (T-R) cycles of 150 years. (ascending order) Dakota Formation (locally deposition in the Western Interior Seaway, and includes the Oak Canyon [?] and Paguate also in terms of Laramide orogenic -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

1457054074479.Pdf

Dead/ands'" Dime Novel'" #4 lXDER;A- ++-~O/ED f'..'ool (P,4-1<f O tE): .slK:.P!~ BEDFFI I Oil5=- Written by: Matt Forbeck Production: Barry Doyle & Hal Mangold Cover Art and Logo: Ron Spencer Interior Art: Kevin Sharpe Maps: Jeff Lahren Special Thanks to: Justin /\chilli. Kelley Foote, Shane & Michelle Hensley. John Hopler, Ann Kolinsky. Ashe Marler. Dave seay. Ethan Skemp. Richard Thomas, Matt Tice. Mike TInney. Stephen Wieck, John Zinser. Dead/ands created by Shane Lacy Hensley werewo!f:The Wild West created by Justin Achilli &Ethan Skemp PINNACLE ENTERTAINMENT GROUP, Inc. elM! STUDIO .. ~." "Iito-" "t< • 'lito'''' ~-. lito-.· Pinnade Entertainment Group, Inc. P.O. Box 10908 Blacksburg. VA 24062-()908 www.peginc.comordeadlandSiiaol.com (BOO) 214-5645 (orders only) DeadIandJ. Dime -.. WciId WesI..he DaclIIrIds Iogo..r>d the P"",ack SUrtlunl If\! Tl"IIdema,'u <If Plnnaele Enteruolnmenl Gmup. In<. ~ The WlId west is. Trademarl< d WMc WOlf. Inc. The White 'M;>If GP'Ie S1udoo lot<> is. R"IIkSI~ Tr.aoern.rt 0( Whole WOlf. inc. C 1997 Pinnae" Enlt!flllnlMrll Group. Inc.. Ind While WOlf. InC. ~!I Rights R<'5tfW:d. _Icd In ,he USA .?~ t;EDt-E.LONS There was something different about this camp, though. The larger tents bore the brassy emblems of Wasatch, the company controlled by Dr. Darius Hellstromme, the most notorious master of steam technology the West had to offer. That wasn't why Ronan was here though-at least not directly. Wasatch was laying dozens of spurs off of their main line on their way toward the coast. -

In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile Among the Apaches of the American Southwest

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 10 Issue 1 Article 6 6-3-2016 In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile among the Apaches of the American Southwest M. Grace Hunt Watkinson Arizona State University at the Tempe Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation Hunt Watkinson, M. Grace (2016) "In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile among the Apaches of the American Southwest," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 10: Iss. 1: 30-43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.10.1.1279 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol10/iss1/6 This Symposium: Genocide Studies, Colonization, and Indigenous Peoples is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In the Land of the Mountain Gods: Ethnotrauma and Exile Among the Apaches of the American Southwest M. Grace Hunt Watkinson Arizona State University Tempe, AZ, USA Abstract: In the mid to late nineteenth century, two Indigenous groups of New Mexico territory, the Mescalero and the Chiricahua Apaches, faced violence, imprisonment, and exile. During a century of settler influx, territorial changeovers, vigilante violence, and Indian removal, these two cousin tribes withstood an experience beyond individual pain best described as ethnotrauma. Rooted in racial persecution and mass violence, this ethnotrauma possessed layers of traumatic reaction that not only revolved around their ethnicity, but around their relationship with their home lands as well.