MIERS, Sir (Henry)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

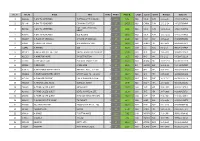

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

NCV Issue 7 2018.Indd

Locally Owned and Operated Est. 2000 FREE! Vol. 18 - Issue 7 • July 11, 2018 - August 8, 2018 INSIDE: Winery Guide Vintage Ohio August, 3rd & 4th Great Lakes Medieval Faire! July 14 – Aug. 19th Painesville Party in the Park, July 13th – 15th Interviews - Colin Dussault, Marion Ross & Allen Ravenstine The Amphicar Celina Swim-In Entertainment, Dining & Leisure Connection Read online at www.northcoastvoice.com North Coast Voice OLD FIREHOUSE 5499 Lake RoadWINERY East • Geneva-on-the Lake, Ohio Restaurant & Tasting Room Live Entertainment 7 Days! (See inside back cover for listings) Hours: Sun- urs Noon to 7pm, Entertainment Fri & Sat Noon to 11pm Tasting Rooms 1-800-Uncork-1 all weekend. (see ad on pg. 5) FOR ENTERTAINMENT AND Kitchen Open! EVENTS, SEE OUR AD ON PG. 7 Summer Hours: Mon. - Closed Hours: Mon 12-4 wine sales Tue., Wed. & ur. Noon – 7 Tues. Closed Fri. & Sat. Noon - 11 HUNDLEY Wed 12-7 • Thurs 12-8 • Fri 12 - 9 Sun. Noon - 7 CELLARS Sat 12-10 • Sun 12-5 834 South County Line Road 6451 N. RIVER RD., HARPERSIELD, OHIO 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfi eld, Oh Harpersfi eld, Ohio 44041 WED. 12 - 7, THURS. 12-8 216.973.2711 SAT. 12- 9, SUN. 12-6 440.415.0661 www.laurellovineyards.com www.bennyvinourbanwinery.com WWW.HUNDLEY CELLARS.COM [email protected] [email protected] If you’re in the mood for a palate pleasing wine tasting accompanied by a delectable entree from our restaurant, Ferrante Winery and Ristorante is the place for you! Summer Hours Tasting Room: Mon. - Tues. 10-5 pm One of the newest Wed & Thurs. -

Big Country Rarities Free Downloads Sound & Vision Thing

big country rarities free downloads Sound & Vision Thing. Out of print, underrated, forgotten music, movies, etc. Check comments for links. full discography, rar, etc. Thursday, December 13, 2018. Big Country. Big Country never got the recognition they deserved in the US but still remained a big band in the UK and Europe until the end of their career in the late '90s. Their first 2 albums were produced by Steve Lillywhite, who also worked with U2 and Simple Minds. Thus, they got lumped in with those two bands, as well as The Alarm, as a new wave of anthemic rock of Gaelic origins. They were actually the most seasoned and musically proficient band of that group, right out of the gate as heard on their debut, "The Crossing." They went on to make great albums (except No Place Like Home) for the rest of their career until lead singer Stuart Adamson's tragic suicide in 2000. 3 comments: As an American fan of Big Country, I would disagree that they *never* got the recognition they deserved here. "In A Big Country" was frequently played on the radio and MTV, and I saw them headline at The Fox, one of Atlanta's premier venues, during their first US tour. Enthusiasm didn't carry over to the albums that followed, and in that sense they deserved better in this country. 1983 - The Crossing [Deluxe Edition] 1984 - Steeltown [Deluxe Edition 2014] 1986 - The Seer [Deluxe Edition 2014] 1988 - Peace in Our Time [Deluxe Edition 2014] 1990 - Through A Big Country [Remastered 1996] 1991 - No Place Like Home 1993 - The Buffalo Skinners [Complete Sessions 2019] 1994 - Without The Aid Of A Safety Net [2019] 1995 - Why the Long Face [Deluxe Expanded 2018] 1998 - Restless Natives & rarities 1998 - The Nashville Sessions 1999 - Driving to Damascus [Bonus Tracks] 2001 - Under Cover 2005 - Rarities 2013 - The Journey (w/ Mike Peters) 2017 - Wonderland: The Essential. -

London Festival Reports Exploring the Wines of Virginia Fortnum and Mason’S Wine Collection Muscadet Revisited Eaz Food & Wine Magazine 2018

MAGAZINE FOR MEMBERS OF THE INTERNATIONAL WINE & FOOD SOCIETY EUROPE AFRICA Issue 133 October 2018 LONDON FESTIVAL REPORTS EXPLORING THE WINES OF VIRGINIA FORTNUM AND MASON’S WINE COLLECTION MUSCADET REVISITED EAZ FOOD & WINE MAGAZINE 2018 Chairman’s message October has agreed to continue for a further two year term until the Society been a significant AGM in 2020. Dave is a great Ambassador for the Society and month for many keen oenologist. After his retirement he has bought a vineyard events and in Mendoza, Argentina, and is keen for us to try his first formalities, not vintages. Those attending the next Triennial Festival in 2021 in only did we hold Argentina I am sure are in for a treat. our first Members’ Forum After Chairing the Council Meeting in Québec my two-year but also our term as Chair of the International Council of Management came Europe Africa to an end. It is nice to report that the Society remains in a sound AGM in Bristol financial position due to good all round management, and it and the Society has been a privilege to further the aims of the Society and seek AGM in Québec. consensus of the other Council Members whose views occasionally pull us in different directions. At the end of the The turnout for the Bristol Great Weekend, Members’ Forum meeting I was pleased to hand over the Chairman’s Chain of and EAZ AGM was very pleasing with many members Office to Andrew Jones of the Americas, who will be Chair for participating and it gave plenty of time for socialising, the next two years. -

The Role of Women in Peace Processes and Conflict Resolution a Comparative Case Study of Northern Ireland Roundtable Meeting

The Role of Women in Peace Processes and Conflict Resolution A Comparative Case Study of Northern Ireland Roundtable Meeting Report Barış Süreçlerinde ve Çatışma Çözümünde Kadınların Rolü Kuzey İrlanda Karşılaştırmalı İnceleme Çalışması Yuvarlak Masa Toplantı Raporu Ankara 29 July | Temmuz 2017 The Role of Women in Peace Processes and Conflict Resolution A Comparative Case Study of Northern Ireland Roundtable Meeting Report Ankara 29 July 2017 3 Published by / Yayınlayan Democratic Progress Institute – Demokratik Gelişim Enstitüsü 11 Guilford Street London WC1N 1DH www.democraticprogress.org [email protected] + 44 (0) 20 7405 3835 First published / İlk Baskı, 2017 ISBN: 978-1-911205-19-7 © DPI – Democratic Progress Institute / Demokratik Gelişim Enstitüsü DPI – Democratic Progress Institute is a charity registered in England and Wales. Registered Charity No. 1037236. Registered Company No. 2922108 DPI – Demokratik Gelişim Enstitüsü İngiltere ve galler’de kayıtlı bir vakıftır. Vakıf kayıt No. 1037236. Kayıtlı Şirket No. 2922108 This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable.be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable. Bu yayının telif hakları saklıdır, eğitim amacıyla telif ödenmeksizin yada önceden izin alınmaksızın çoğaltılabilir ancak yeniden satılamaz. Bu durumun dışındaki her tür kopyalama için yayıncıdan yazılı izin alınması gerekmektedir. Bu durumda yayıncılara bir ücret ödenmesi gerekebilir. 4 The Role of Women in Peace Processes and Conflict Resolution Contents Foreword ...................................................................................6 Opening Remarks Prof. Dr. Sevtap Yokuş ................................................................9 When Women are Up Against It: Looking for Opportunities to Make Progress Dr. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Dialogue in Difficult Times: the Cases of Northern Ireland and the Philippines

Dialogue in Difficult Times: The Cases of Northern Ireland and the Philippines Roundtable Meeting, Ankara, Turkey 4th March 2017 Table of Contents FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 OPENING SPEECH: KEZBAN HATEMI ....................................................................................................................... 6 SESSION ONE ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 DAVID GORMAN .......................................................................................................................................................... 11 LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE PHILIPPINES PROCESS: HOW TO GET THE PROCESS BACK ON TRACK AFTER EXPERIENCING SETBACKS ....... 11 Q&A ......................................................................................................................................................................... 22 SESSION TWO ...................................................................................................................................................... 29 SIR BILL JEFFREY ........................................................................................................................................................... 29 THE CHOREOGRAPHY OF THE PEACE PROCESS: CONFLICT RESOLUTION DURING DIFFICULT TIMES ................................................. -

Big Country Book of Lyrics Was Originally Offered Online As a PDF File on a Web Site That Later Grew Into the Current Steeltown Site

D e s i g n e d b y R o b e r t O l i v e r Introduction Project History The Big Country Book of Lyrics was originally offered online as a PDF file on a web site that later grew into the current Steeltown site. Since I had not been pleased with the formatting restrictions of HTML, I had decided to create a file in Adobe PageMaker and then convert it into a PDF (Portable Document Format) file. This format allows complete control over layout and typography, but can result in very large files. Although PDF files are relatively small compared to their original documents (all of the original PageMaker files for this book total over 18 megabytes), a project as large and comprehensive as the Big Country Book of Lyrics results in an appropriately hefty PDF file. Even though I have since converted all lyrics to HTML and incorporated them into the Steeltown web site, the PDF version is still a handy and useful resource, especially when printed and bound for reference. As ubiquitous as the world wide web has become, a printed version of the Book of Lyrics is easier on the eyes, quicker to thumb through, and does not require an internet connection. Document Navigation The following methods are available for finding your way around the Big Country Book of Lyrics while using the Adobe Acrobat Reader: 1. Scan down the bookmark list on the left and click on the item of interest. 2. Use the keyboard arrow keys or the PAGE UP and PAGE DOWN keys depending on which version of the Acrobat Reader you are using. -

Science & Innovation Annual Report

s&I - covers 22/07/2005 4:46 PM Page 2 Science & Innovation Annual Report 2004-2005 Science & Innovation Network s&I - covers 22/07/2005 4:46 PM Page d S&Tech text 22/07/2005 10:34 AM Page 1 Foreword By Dr Ian Pearson MP Science and innovation are The Science and Innovation Network works with government 1 moving up government departments, businesses and academia, all of whom share an agendas throughout the interest in international science.The Network promotes the world. Science underpins our response to international UK as partner of choice for research and development and Dr Ian Pearson MP concerns such as climate inward investment in science and technology. It helps facilitate change, energy security, international trade in the high technology sectors. It adds infectious diseases, economic governance and sustainable value to UK science policy, and uses science to underpin development. It is central to our foreign policy. international policy. This Government is committed to making UK science and innovation among the best in the world.The Foreign and The Network fosters international research by bringing UK Commonwealth Office (FCO) Science and Innovation scientists, students and funding bodies together with their Network, which is deployed in a wide range of leading science counterparts from other countries. Science officers work nations, takes forward our international plans for with their commercial colleagues overseas and Department strengthening UK science.As the Minister responsible for science within the FCO, I will be participating in a new of Trade and Industry to identify new and emerging Cabinet committee on Science, Innovation and the technologies and encourage collaboration between Knowledge Economy as part of this process. -

(CUWS) Outreach Journal Issue 1300

Issue No. 1300 2 February 2018 // USAFCUWS Outreach Journal Issue 1300 // Feature Item “Iran Sanctions”. Written by Kenneth Katzman, published by the Congressional Research Service; January 17, 2018 https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/RS20871.pdf U.S. sanctions—and U.S. attempts to achieve imposition of multilateral and international sanctions on Iran—have been a significant component of U.S. Iran policy for several decades. In the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. sanctions were intended to try to compel Iran to cease supporting acts of terrorism and to limit Iran’s strategic power in the Middle East more generally. Since the mid2000s, U.S. sanctions have focused on ensuring that Iran’s nuclear program is for purely civilian uses and, since 2010, the international community has cooperated with a U.S.-led and U.N.- authorized sanctions regime in pursuit of that goal. Still, sanctions against Iran have multiple objectives and address multiple perceived threats from Iran simultaneously. This report analyzes U.S. and international sanctions against Iran and provides some examples, based on open sources, of companies and countries that conduct business with Iran. CRS has no way to independently corroborate any of the reporting on which these examples are based and no mandate to assess whether any firm or other entity is complying with U.S. or international sanctions against Iran. twitter.com/USAF_CUWS | cuws.au.af.mil // 2 // USAFCUWS Outreach Journal Issue 1300 // TABLE OF CONTENTS US NUCLEAR WEAPONS A Microscopic Fungus Could Mop Up Our Cold War-era Nuclear Waste Trump: We Must 'Modernize and Rebuild' Nuclear Arsenal USS Wyoming Arrives in Norfolk for Overhaul AEDC Stands Up ICBM Combined Test Force at Hill Air Force Base US COUNTER-WMD Another US Navy Ballistic Missile Intercept Reportedly Fails in Hawaii Army Taps Lockheed for 10 More THAAD Interceptors Is the Army Ready to Transform its Missile Defense Force? New Army Missile Defense Strategy Due Out This Summer Missile Defense Vs. -

Peace Proms 2011/2012 Invitation to Sing… SUPPORTED by Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht Affairs Department of Education and Skills

Peace Proms 2011/2012 Invitation to sing… SUPPORTED BY Department of Arts, Heritage and Gaeltacht Affairs Department of Education and Skills CBOI sells out Chicago Symphony Hall and Carnegie Hall, New York 2 ENDORSEMENTS Dear Sharon, It gives me great pleasure to send my warmest greetings to the Cross Border Orchestra of Ireland. In addition to providing a platform for some of the most talented young musicians across Ireland, the Cross Border Orchestra has made an immense contribution to peace and reconciliation on this island. I wish the musicians and members of the Cross Border Orchestra the very best as they bring their own unique blend of peace, hope and remarkable musical talent to audiences at home and abroad. MARY McALEESE PRESIDENT OF IRELAND Dear Friends: Since 1995, the members of the Cross Border Orchestra of Ireland have entertained and enlightened audiences across Europe and North America. Your commitment to musical excellence is only surpassed by the remarkable devotion you share for building bridges of understanding among communities of the border counties of Ireland. Together, you have transformed lives and, in the process, changed entire communities for the better. As you prepare to dazzle yet another audience, please accept my sincere congratulations for all your magnificent achievements. With friendship and best wishes, I remain Sincerely yours, HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON Dear Friends, I am delighted to endorse the excellent work of the Cross Border Orchestra of Ireland, which brings together young people from both sides of the border through the reconciling medium of music. The orchestra represents the best in the proud traditions of this island and seeks to promote peace and reconciliation and to offer the hope of a better future for the next generation. -

Annual Report 2018 Our Mission to Broaden Bases for Public Involvement in Promoting Peace and Democracy

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Our mission To broaden bases for public involvement in promoting peace and democracy. Our unique model combines expertise and research with practical inclusive platforms for dialogue. 11 Guilford Street, London WC1N 1DH United Kingdom democraticprogress.org +44 (0) 207 405 3835 @ [email protected] DemocraticProgressInstitute @DPI_UK Registered charity no. 1037236 Registered company no. 2922108 All photos © Democratic Progress Institute Design and layout: revangeldesigns.co.uk Contents Introduction by Kerim Yildiz, Chief Executive Officer 4 About DPI 6 Our values 6 Our aims and objectives 6 Our methods 7 Our key themes 8 Our impact in 2018 11 Our programme in 2018 14 Broadening bases of discussion 14 Women’s role in conflict resolution 14 Roundtable: Women’s role in dialogue and conflict resolution in challenging times: Working together to address issues of common interest 14 Roundtable: The role of women in conflict resolution: Reflecting on the Turkish experience 16 The role of the media in conflict resolution 17 Roundtable: The role of media in conflict resolution, hosted by the Norwegian Ministry of Public Affairs 17 Roundtable: The role of media in conflict resolution, hosted by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 18 Public Engagement in Conflict Resolution 19 Comparative Study Visit: Public engagement in conflict resolution processes, hosted by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 19 The role of youth in conflict resolution 22 Comparative Study Visit: Youth engagement in conflict resolution