Constantine, the Tetrarchy, and the Emperor Augustus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Exam Sample Question

Latin II St. Charles Preparatory School Sample Second Semester Examination Questions PART I Background and History (Questions 1-35) Directions: On the answer sheet cover the letter of the response which correctly completes each statement about Caesar or his armies. 1. The commander-in-chief of a Roman army who had won a significant victory was known as a. dux b. imperator c. signifer d. sagittarius e. legatus 2. Caesar was consul for the first time in the year a. 65 B.C. b. 70 B.C. c. 59 B.C. d. 44 B.C. e. 51 B.C. PART II Vocabulary (Questions 36-85) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the correct meaning for the boldfaced Latin word in the left band column. 36. doctus a. edge b. entrance c. learned d. record e. friendly 37. incipio a. stop b. speaker c. rest d. happen e. begin PART III Prepared Translation, Passage A (Questions 86-95) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 86. Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres. a. The Gauls divided themselves into three parts b. All of Gaul was divided into three parts c. Three parts of Gaul have been divided d. Everyone in Gaul was divided into three parts PART IV Prepared Translation, Passage B (Questions 96-105) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 96. Galli se Celtas appellant. Romani autem eos Gallos appellant. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

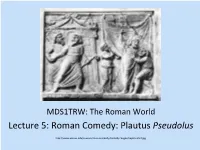

Lecture 5: Roman Comedy: Plautus Pseudolus

MDS1TRW: The Roman World Lecture 5: Roman Comedy: Plautus Pseudolus h"p://www.utexas.edu/courses/moorecomedy/comedyimages/naplesrelief.jpg ROMAN COMEDY fabula palliata – story in Greek dress • Plautus (c. 254 to 184 BCE) – 20 comedies including Pseudolus • Terence (195-160 BCE) - 6 comedies Italian influences on the fabula palliata • Fescennine Jesng – obscene abuse, verbal duelling [e.g. Pseudolus and Simia (Pseud. 913-20 – pp. 251-2)] • Saturnalia 17 December - overturning of social norms [e.g. slave in charge mo\f] • Atellan Farce: innuendo, obscenity, visual comedy [everywhere! – see Ballio and slaves scene] Plautus vs. Terence • Terence: v Athenian New Comedy v family drama • Plautus: v Roman elements • e.g. Aulularia (Pot of Gold 107): Euclio visits the Roman magistrate v Farce v Metatheatrics Performing Plautus’ Pseudolus • 191 BCE • Ludi Megalenses • Plautus = 63 years old Mosaic of two actors with masks Sousse Museum, Tunisia http://www.vroma.org/images/mcmanus_images/paula_chabot/theater/pctheater40.jpg Plautus: use of stock characters • Young man (adulescens) • Slave (servus, ancilla) • Old man (senex) • Pros\tute (meretrix) • Pimp, bawd (leno) • Soldier (miles) • Parasite (parasitus) Mosaic of comic masks: flute girl and • Nurse (nutrix) slave, Conservatori Museum, Rome http://www.vroma.org/images/mcmanus_images/paula_chabot/theater/pctheater.30.jpg Plautus: stock characters in Pseudolus • Young man (adulescens) - Calidorus • Slave (servus) – Pseudolus [and Simia] • Old man (senex) – Simo • Pimp, bawd (leno) – Ballio • Cook (coquus) –unnamed • Pros\tute (meretrix) - Phoenicium Mosaic of comic masks: flute girl and slave, Conservatori Museum, Rome http://www.vroma.org/images/mcmanus_images/paula_chabot/theater/pctheater.30.jpg Names with meaning • Slaves: Pseudolus; Harpax; Simia • Soldier: Polymachaeroplagides = lit. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Roman Republic to Roman Empire

Roman Republic to Roman Empire Start of the Roman Revolution By the second century B.C., the Senate had become the real governing body of the Roman state. Members of the Senate were usually wealthy landowners, and they remained Senators for life. Rome’s government had started out as a Republic in which citizens elected people to represent them. But the Senate was filled with wealthy aristocrats who were not elected. Rome was slowly turning into an aristocracy, and the majority of middle and lower class citizens began to resent it. Land was usually at the center of class struggles in Rome. The wealthy owned most of the land while the farmers had found themselves unable to compete financially with the wealthy landowners and had lost most of their lands. As a result, many of these small farmers drifted to the cities, especially Rome, forming a large class of landless poor. Changes in the Roman army soon brought even worse problems. Starting around 100 B.C. the Roman Republic was struggling in several areas. The first was the area of expansion. The territory of Rome was expanding quickly and the republic form of government could not make decisions and create stability for the new territories. The second major struggle was that due to expansion, the Republic was also experiencing problems with collecting taxes from its citizens. The larger area of the growing Roman territory created difficulties with collecting taxes from a larger population. Government officials had to go to each town, this would take several months to reach the whole extent of Roman territory. -

The Extension of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 285-305Ce

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 The Extension Of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian And The Tetrarchy, 285-305ce Joshua Petitt University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Petitt, Joshua, "The Extension Of Imperial Authority Under Diocletian And The Tetrarchy, 285-305ce" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2412. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2412 THE EXTENSION OF IMPERIAL AUTHORITY UNDER DIOCLETIAN AND THE TETRARCHY, 285-305CE. by JOSHUA EDWARD PETITT B.A. History, University of Central Florida 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 © 2012 Joshua Petitt ii ABSTRACT Despite a vast amount of research on Late Antiquity, little attention has been paid to certain figures that prove to be influential during this time. The focus of historians on Constantine I, the first Roman Emperor to allegedly convert to Christianity, has often come at the cost of ignoring Constantine's predecessor, Diocletian, sometimes known as the "Second Father of the Roman Empire". The success of Constantine's empire has often been attributed to the work and reforms of Diocletian, but there have been very few studies of the man beyond simple biography. -

From Republic to Empire

FROM REPUBLIC TO EMPIRE A PRESENTATION BY: JACKSON WILKENS,ANDREW DE GALA, AND CHRISTIAN KOPPANG ESTABLISHMENT OF THE PRINCIPATE 1. Augustus Caesar (30BCE-14CE) 2. Augustus as imperator 3. Further conquests AUGUSTUS CAESAR,THE FIRST CAESAR • Augustus (63BCE-14AD) was the first emperor of Rome after his adoptive father, Julius Caesar, was assassinated by the Roman senate. • His rise to power was because of tactfully combining the Roman military might with the Roman government and its lawmaking. • He lay the foundation for the 200 years of peace, Pax Romana. • Finally he set up an empire that would last for in one form or another for 1500 years. AUGUSTUS` ASCENSION TO POWER • Augustus` ascension to power began with having to battle with Mark Antony, a powerful rival. • Augustus` troops beat Mark Antony and set up an uneasy alliance with the rival leader in the form of a triumvirate government with himself, Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus, a minor leader. • Mark Antony was forming a political alliance with Cleopatra of Egypt forcing Augustus to declare war against Cleopatra. • In 32BCE a naval battle occurred between Mark Antony and Cleopatra against Augustus. Augustus defeated the enemy fleet and his enemies committed suicide leaving Augustus the undisputed leader of Rome. AUGUSTUS` RULE AND GOLDEN AGE • During Augustus` rule he set up: -Alliances where Rome had influence over lands in India and the British Isles. -Doubled the size of the Empire with territories in Europe and Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). -Instituted many censuses and a system for even the furthest of provinces of Rome -Founded a body-guard organization for protecting himself and future emperors of Rome, the Praetorian Guard -The Roman postal service -Established Roman police force and firefighters -Beautified and improved the capital city, Rome AUGUSTUS AS IMPERATOR • The title Imperator is bestowed upon a commander when they have won a major victory. -

The Roman Emperors

BIBLE LANDS NOTES: Emperors of Rome 1 Emperors of Rome 1. Augustus (Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus) • Born at Rome on September 23, 63 B.C. • Died at Nola in Campania on August 19, 14 A.D. at age 77 from an illness • Reigned 41 years, from 27 B.C. to 14 A.D. • Augustus was the first Roman emperor, a grand-nephew of Julius Caesar. He reigned at the time of the birth of Jesus Christ (Luke 2:1). 2. Tiberius (Tiberius Caesar Augustus) • Born at Rome on November 16, 42 B.C. • Died at Misenum on March 16, 37 A.D. at age 79 from being smothered with a pillow while on his death bed from a terminal illness (he wasn't dying fast enough for his successor's liking) • Reigned 23 years, from 14 to 37 A.D. • Tiberius was emperor at the time of the ministry and crucifixion of Jesus Christ (Luke 3:1) 3. Caligula (Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus) • Born at Antium (Anzio) on August 31, 12 A.D. • Died at Rome on January 24, 41 A.D. at age 19 from assassination • Reigned 4 years, from 37 to 41 A.D. 4. Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus) • Born at Lugdunum on August 1, 10 B.C. • Died at Rome on October 13, 54 A.D. at age 64 from eating deliberately poisoned mushrooms given to him by his wife Agrippina (Nero's mother). • Reigned 13 years, from 41 to 54 A.D. BIBLE LANDS NOTES: Emperors of Rome 2 5. Nero (Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus) • Born at Antium (Anzio) on December 15, 37 A.D. -

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500

Ancient Rome and Early Christianity, 500 B.C.-A.D. 500 Previewing Main Ideas POWER AND AUTHORITY Rome began as a republic, a government in which elected officials represent the people. Eventually, absolute rulers called emperors seized power and expanded the empire. Geography About how many miles did the Roman Empire stretch from east to west? EMPIRE BUILDING At its height, the Roman Empire touched three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa. For several centuries, Rome brought peace and prosperity to its empire before its eventual collapse. Geography Why was the Mediterranean Sea important to the Roman Empire? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Out of Judea rose a monotheistic, or single-god, religion known as Christianity. Based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, it soon spread throughout Rome and beyond. Geography What geographic features might have helped or hindered the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps Go to classzone.com for: • Interactive Visuals • Research Links • Maps • Interactive Primary Sources • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 152 153 What makes a successful leader? You are a member of the senate in ancient Rome. Soon you must decide whether to support or oppose a powerful leader who wants to become ruler. Many consider him a military genius for having gained vast territory and wealth for Rome. Others point out that he disobeyed orders and is both ruthless and devious. You wonder whether his ambition would lead to greater prosperity and order in the empire or to injustice and unrest. ▲ This 19th-century painting by Italian artist Cesare Maccari shows Cicero, one of ancient Rome’s greatest public speakers, addressing fellow members of the Roman Senate. -

Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus Divi Filius Augustus Samulus Maximus Source: Mrs

Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus Divi Filius Augustus Samulus Maximus Source: Mrs. Robinson’s notes and www.roman-emperors.org Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus Divi Filius Augustus passed away at the age of 76 on August 19, 14 A.D. in Nola, Italy The cause of death is unspecified. Augustus was the founder of the Roman Empire, its first Emperor. He ruled from 27 B.C. until his death in 14 A.D. His parents were Atia and Gaius Octavius. His sibling was Octavia Minor. He had three spouses; Clodia Pulchra (42 B.C. – 40 B.C.), Scribonia (40 B.C.-38 B.C.), and Livia (37 B.C. – 14 A.D.). His daughter is Julia and his adopted son is Tiberius. His two adopted grandchildren are Gaius and Lucius Agrippa. He lived simply and desired peace, order, and stability as emperor of Rome. Augustus had had many major accomplishments and achievements throughout his life. He paid the soldiers. He also paid good governors and removed corrupt ones. Augustus put soldiers on the borders of his empire to protect his people. He taxed fairly to pay for roads, bridges, aqueducts, monuments, temples, library, theatres, police and fire departments, postal system, and the civil service system. Augustus gave citizenship to people living in provinces and gave land to the veterans. He publicly gave power to the Senate because Caesar did not last long as a dictator. Augustus ended the civil wars. He improved sanitation, constructed new buildings, and streamlined the city’s civil administration. As many say, “Augustus found Rome in brick and left it in marble.” The funeral service will be held at Nola Cemetery on the 29 of August 14, A.D.