Lecture 5: Roman Comedy: Plautus Pseudolus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Exam Sample Question

Latin II St. Charles Preparatory School Sample Second Semester Examination Questions PART I Background and History (Questions 1-35) Directions: On the answer sheet cover the letter of the response which correctly completes each statement about Caesar or his armies. 1. The commander-in-chief of a Roman army who had won a significant victory was known as a. dux b. imperator c. signifer d. sagittarius e. legatus 2. Caesar was consul for the first time in the year a. 65 B.C. b. 70 B.C. c. 59 B.C. d. 44 B.C. e. 51 B.C. PART II Vocabulary (Questions 36-85) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the correct meaning for the boldfaced Latin word in the left band column. 36. doctus a. edge b. entrance c. learned d. record e. friendly 37. incipio a. stop b. speaker c. rest d. happen e. begin PART III Prepared Translation, Passage A (Questions 86-95) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 86. Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres. a. The Gauls divided themselves into three parts b. All of Gaul was divided into three parts c. Three parts of Gaul have been divided d. Everyone in Gaul was divided into three parts PART IV Prepared Translation, Passage B (Questions 96-105) Directions: On the answer sheet provided cover the letter of the best translation for each Latin sentence or fragment. 96. Galli se Celtas appellant. Romani autem eos Gallos appellant. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Ius Militare – Military Courts in the Roman Law (I)

International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) ISSN 2307-4531 (Print & Online) http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ius Militare – Military Courts in the Roman Law (I) PhD Dimitar Apasieva*, PhD Olga Koshevaliskab a,bGoce Delcev University – Shtip, Shtip 2000, Republic of Macedonia aEmail: [email protected] bEmail: [email protected] Abstract Military courts in ancient Rome belonged to the so-called inconstant coercions (coercitio), they were respectively treated as “special circumstances courts” excluded from the regular Roman judicial system and performed criminal justice implementation, strictly in conditions of war. To repress the war torts, as well as to overcome the soldiers’ resistance, which at moments was violent, the king (rex) himself at first and the highest new established magistrates i.e. consuls (consules) afterwards, have been using various constrained acts. The authority of such enforcement against Roman soldiers sprang from their “military imperium” (imperium militiae). As most important criminal and judicial organs in conditions of war, responsible for maintenance of the military courtesy, were introduced the military commander (dux) and the array and their subsidiary organs were the cavalry commander, military legates, military tribunals, centurions and regents. In this paper, due to limited available space, we will only stick to the main military courts in ancient Rome. Keywords: military camp; tribunal; dux; recruiting; praetor. 1. Introduction “[The Romans...] strictly cared about punishments and awards of those who deserved praise or lecture… The military courtesy was grounded at the fear of laws, and god – for people, weapon, brad and money are the power of war! …It was nothing more than an army, that is well trained during muster; it was no possible for one to be defeated, who knows how to apply it!” [23]. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Emperors and Generals in the Fourth Century Doug Lee Roman

Emperors and Generals in the Fourth Century Doug Lee Roman emperors had always been conscious of the political power of the military establishment. In his well-known assessment of the secrets of Augustus’ success, Tacitus observed that he had “won over the soldiers with gifts”,1 while Septimius Severus is famously reported to have advised his sons to “be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and despise the rest”.2 Since both men had gained power after fiercely contested periods of civil war, it is hardly surprising that they were mindful of the importance of conciliating this particular constituency. Emperors’ awareness of this can only have been intensified by the prolonged and repeated incidence of civil war during the mid third century, as well as by emperors themselves increasingly coming from military backgrounds during this period. At the same time, the sheer frequency with which armies were able to make and unmake emperors in the mid third century must have served to reinforce soldiers’ sense of their potential to influence the empire’s affairs and extract concessions from emperors. The stage was thus set for a fourth century in which the stakes were high in relations between emperors and the military, with a distinct risk that, if those relations were not handled judiciously, the empire might fragment, as it almost did in the 260s and 270s. 1 Tac. Ann. 1.2. 2 Cass. Dio 76.15.2. Just as emperors of earlier centuries had taken care to conciliate the rank and file by various means,3 so too fourth-century emperors deployed a range of measures designed to win and retain the loyalties of the soldiery. -

LUCAN's CHARACTERIZATION of CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH By

LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY (Under the Direction of Thomas Biggs) ABSTRACT This thesis examines Caesar’s three extended battle exhortations in Lucan’s Bellum Civile (1.299-351, 5.319-364, 7.250-329) and the speeches that accompany them in an effort to discover patterns in the character’s speech. Lucan did not seem to develop a specific Caesarian style of speech, but he does make an effort to show the changing relationship between the General and his soldiers in the three scenes analyzed. The troops, initially under the spell of madness that pervades the poem, rebel. Caesar, through speech, is able to bring them into line. Caesar caters to the soldiers’ interests and egos and crafts his speeches in order to keep his army working together. INDEX WORDS: Lucan, Caesar, Bellum Civile, Pharsalia, Cohortatio, Battle Exhortation, Latin Literature LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY B.A., The College of Wooster, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth Talbot Neely All Rights Reserved LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY Major Professor: Thomas Biggs Committee: Christine Albright John Nicholson Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

Objective and Subjective Genitives

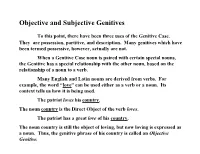

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Flavius Athanasius, Dux Et Augustalis Thebaidis – a Case Study on Landholding and Power in Late Antique Egypt

Imperium and Officium Working Papers (IOWP) Flavius Athanasius, dux et Augustalis Thebaidis – A case study on landholding and power in Late Antique Egypt Version 01 March 2013 Anna Maria Kaiser (University of Vienna, Department of Ancient History, Papyrology and Epigraphy) Abstract: From 565 to 567/568 CE Flavius Triadius Marianus Michaelius Gabrielius Constantinus Theodorus Martyrius Iulianus Athanasius was dux et Augustalis Thebaidis. Papyri mention him explicitly in this function, as the highest civil and military authority in the Thebaid, the southernmost province of the Eastern Roman Empire. Flavius Athanasius might be not the most typical dux et Augustalis Thebaidis concerning his career, but most typical concerning his powerful standing in society. And he has the benefit of being one of the better- known duces et Augustales Thebaidis in the second half of the 6th century. This article will focus first on his official competence as dux et Augustalis: The geographic area(s) of responsibility, the civil and military branches of power will be treated. Second will be his civil branch of power; documents show his own domus gloriosa and prove his involvement with the domus divina, the estates of members of the imperial family itself. We will end with a look at his integration in the network of power – both in the Egyptian provinces and beyond. © Anna Maria Kaiser 2013 [email protected] Anna Kaiser 1 Flavius Athanasius, dux et Augustalis Thebaidis – A case study on landholding and power in Late Antique Egypt* Anna Maria Kaiser From 565 to 567/568 CE Flavius Triadius Marianus Michaelius Gabrielius Constantinus Theodorus Martyrius Iulianus Athanasius was dux et Augustalis Thebaidis. -

Bowling Green Alumni Association Announces

THE AREA’S ONLY LOCALLY-OWNED & OPERATED NEWSPAPER | EST. OCTOBER 1, 1996 HE EOPLE S RIBUNE TNEWS FOR PIKEP, EASTERN AUDRAIN’& NORTHERNT LINCOLN COUNTIES FREE Published Every Tuesday • Vol. 26 - No. 42 • Tuesday, Aug. 3, 2021 • Online at www.thepeoplestribune.com Bowling Green Alumni Association Announces BanquetBY BRICE Speaker,CHANDLER EntertainmentLynyrd Skynyrd, The Allman Broth- STAFF WRITER ers, The Dave Matthews Band, and First held in 1985, the Bowling more. Green Alumni Association hosts its According to his bio, “Powell's annual alumni banquet each fall to work has been included on multiple honor graduating classes of the past gold and platinum records with nine and celebrate the education and different Grammy winning proj- memories of those important years ects.” at Bowling Green High School. Not only has he worked on such The organization also updates notable projects, but Powell has also members on one of its founding pur- cut vinyl records for the last 13- poses – the status of scholarships years with the Sam Phillips Record- awarded each year to graduating ing Service and his own company, seniors. Take Out “To date, Vinyl. the association Powell met has awarded his wife of 28- more than years, Susan, $411,050 in during a scholarships,” recording ses- the group sion at Ardent stated in its re- Studios for a cent banquet new band registration called The form. “Includ- Mother Sta- ing eighteen tion. $1,000 schol- When not Hot Weather arships to in the studio, 2020 gradu- “he remains a ates and six- diehard Saint teen $1,000 Louis Cardi- Did Not Deter scholarships to nals fan.” 2021 gradu- Attendees ates.” of this year's To celebrate banquet will Pike County Fair the accom- also be treated plishment and camaraderie, the as- to entertainment from an alumni sociation invites special guest choir under the direction of retired speakers and entertainers for a night vocal music instructor, Jack Bibb. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Roman Republic to Roman Empire

Roman Republic to Roman Empire Start of the Roman Revolution By the second century B.C., the Senate had become the real governing body of the Roman state. Members of the Senate were usually wealthy landowners, and they remained Senators for life. Rome’s government had started out as a Republic in which citizens elected people to represent them. But the Senate was filled with wealthy aristocrats who were not elected. Rome was slowly turning into an aristocracy, and the majority of middle and lower class citizens began to resent it. Land was usually at the center of class struggles in Rome. The wealthy owned most of the land while the farmers had found themselves unable to compete financially with the wealthy landowners and had lost most of their lands. As a result, many of these small farmers drifted to the cities, especially Rome, forming a large class of landless poor. Changes in the Roman army soon brought even worse problems. Starting around 100 B.C. the Roman Republic was struggling in several areas. The first was the area of expansion. The territory of Rome was expanding quickly and the republic form of government could not make decisions and create stability for the new territories. The second major struggle was that due to expansion, the Republic was also experiencing problems with collecting taxes from its citizens. The larger area of the growing Roman territory created difficulties with collecting taxes from a larger population. Government officials had to go to each town, this would take several months to reach the whole extent of Roman territory.