Cop Confidential 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sing out Loud Music Festival Schedule

SING OUT LOUD FESTIVAL, THE FREE, MULTI-DAY, MULTI-VENUE MUSIC FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FESTIVAL SCHEDULE FEATURING OVER 200 ARTISTS PLAYING 50 SHOWCASES AT 15 VENUES AROUND ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA PRESENTED BY COMMUNITY FIRST CREDIT UNION St. Augustine, Fla. (August 14, 2017) – Nine days, 15 venues, 50 showcases, over 200 performing artists. All free and open to the public. This is the Sing Out Loud Festival, the largest free music festival ever held in North Florida. The official Sing Out Loud schedule is now available, detailing the epic celebration of live entertainment that will take place throughout St. Augustine, Florida for three weekends this September. The schedule with full performance lineups, show times and locations is available online at www.singoutloudfestival.com/schedule. The Sing Out Loud Festival is presented by Community First Credit Union and produced by the St. Johns County Cultural Events Division with support from St. Johns County Tourist Development Council, the St. Johns Cultural Council and the St. Augustine, Ponte Vedra, & The Beaches Visitors and Convention Bureau. In a convergence of musical genres as wide ranging as Texas Outlaw Country, New Orleans Brass and Funk, Alternative Indie Rock, Americana, Bluegrass, Neo-Soul, Folk, Punk, Hip Hop, Spoken Word, Comedy, Electronic and more, the Sing Out Loud Music Festival, now in its second year, has expanded to include over 200 national, local and regional acts playing 50 showcases at 15 St. Augustine venues during September 8 – 10, 15 -17 and 22 - 24. The free, multi-day, multi-venue festival features national acts including Steve Earle & the Dukes, Lake Street Dive, Wolf Parade, Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Los Lobos and more in addition to a massive regional and local lineup. -

Heroes (TV Series) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Pagina 1 Di 20

Heroes (TV series) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pagina 1 di 20 Heroes (TV series) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Heroes was an American science fiction Heroes television drama series created by Tim Kring that appeared on NBC for four seasons from September 25, 2006 through February 8, 2010. The series tells the stories of ordinary people who discover superhuman abilities, and how these abilities take effect in the characters' lives. The The logo for the series featuring a solar eclipse series emulates the aesthetic style and storytelling Genre Serial drama of American comic books, using short, multi- Science fiction episode story arcs that build upon a larger, more encompassing arc. [1] The series is produced by Created by Tim Kring Tailwind Productions in association with Starring David Anders Universal Media Studios,[2] and was filmed Kristen Bell primarily in Los Angeles, California. [3] Santiago Cabrera Four complete seasons aired, ending on February Jack Coleman 8, 2010. The critically acclaimed first season had Tawny Cypress a run of 23 episodes and garnered an average of Dana Davis 14.3 million viewers in the United States, Noah Gray-Cabey receiving the highest rating for an NBC drama Greg Grunberg premiere in five years. [4] The second season of Robert Knepper Heroes attracted an average of 13.1 million Ali Larter viewers in the U.S., [5] and marked NBC's sole series among the top 20 ranked programs in total James Kyson Lee viewership for the 2007–2008 season. [6] Heroes Masi Oka has garnered a number of awards and Hayden Panettiere nominations, including Primetime Emmy awards, Adrian Pasdar Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards and Zachary Quinto [2] British Academy Television Awards. -

WINNIE VERLOC and HEROISM in the SECRET AGENT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Parti

7w WINNIE VERLOC AND HEROISM IN THE SECRET AGENT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Cynthia Joy Henderson, B.A. Denton, TX May, 1993 Henderson, Cynthia Joy. Winnie Verloc and Heroism in The Secret Agent. Master of Arts (English), May 1993, 77 pp., bibliography, 65 titles. Winnie Verloc's role in The Secret Agent has received little initial critical attention. However, this character emerges as Conrad's hero in this novel because she is an exception to what afflicts the other characters: institutionalism. In the first chapter, I discuss the effect of institutions on the characters in the novel as well as on London, and how both the characters and the city lack hope and humanity. Chapter II is an analysis of Winnie's character, concentrating on her philosophy that "life doesn't stand much looking into," and how this view, coupled with her disturbing experience of having looked into the "abyss," makes Winnie heroic in her affirmative existentialism. Chapters III and IV broaden the focus, comparing Winnie to Conrad's other protagonists and to his other female characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . - - - - - - - 1 CHAPTER I THE PLAYERS AND THEIR SETTING . 5 CHAPTER II WINNIE . .......... 32 CHAPTER III WINNIE AMONG CONRAD'S MEN AND WOMEN . 60 CHAPTER IV MADNESS AND DESPAIR . 71 WORKS CITED . ... 76 WORKS CONSULTED . ...... 79 iii INTRODUCTION The Secret Agent, although primarily approached by the critics as a political novel, is also a social and a domestic drama played out in the back parlour of a secret agent's pornography shop, and on the dreary streets of London. -

Heroes and Philosophy

ftoc.indd viii 6/23/09 10:11:32 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/23/09 10:11:11 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Family Guy and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by Jason Holt Lost and Philosophy Edited by Sharon Kaye 24 and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Hart Week, and Ronald Weed Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy Edited by Jason T. Eberl The Offi ce and Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Batman and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Robert Arp House and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Watchmen and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Kevin Decker ffirs.indd ii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM HEROES AND PHILOSOPHY BUY THE BOOK, SAVE THE WORLD Edited by David Kyle Johnson John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/23/09 10:11:12 AM This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or autho- rization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750–8400, fax (978) 646–8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. -

GV ABST Reflections

!1 Saturday Devo: None EG: Hi/Lo; “6-Day Visit To Rural African Village” & “The Cost of Short-Term Missions”; Expectations Sunday Devo: A Prayer for Spiritual Freedom EG: Hi/Lo; Seeing God in All Things; God Moment; A Personal Prayer of Pedro Arrupe Monday Devo: Answering the Call EG: Hi/Lo/God; Hat Questions; Closing Prayer; Dedicated Journaling Time Tuesday Devo: When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer EG: (Filler Night, Can Use Four Corners); Hi/Lo/God Wednesday Devo: Welcoming Prayer EG: Capture today in…; Expectations Met?; Why Are Things This Way? Thursday Devo: Unfinished Symphonies EG: Reflection Questions; Thank You Cards; Hi/Lo/God; Dedicated Journaling Time Friday Devo: First Noble Truth EG: Noble Truths Discussion; Meditation on Loving-kindness; Hi/Lo/God Saturday Devo: Prayer of Archbishop Oscar Romero EG: What, So What, Now What? Sunday Monday Tuesday Affirmations !2 Saturday Morning Devotional: None Evening Gathering: Hi/Lo “6-Day Visit To Rural African Village” & “The Cost of Short Term Missions” Starter Questions: What were your first reactions? Do you think there’s some truth to The Onion article? Do you think it’s bad to share your trip like that on social media? Do you think we should have just sent out our money over? Critical about coming back an talking about how it changed us, do you think that’s a bad thing? “Short-term groups are also unable to do effective evangelism” because of cultural and language barriers, is this true? Should we be evangelizing? “Third-world people do not need more rich Christians coming to paint their church and make them feel inadequate.” How does that make you feel? “They do need more humble people willing to share in their lives and sacrifices.” How can we be humble? How can we enter into this solidarity of their lives and sacrifices? “…stop thinking about short-term missions as a service to perform and start thinking of them as a responsibility to learn.” How can we do this? Lets save the discussion about the changes after we’re done for later this week. -

Storytelling in Northern Zambia: Theory, Method, Practice and Other Necessary Fictions

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/137 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Man playing the banjo, Kaputa (northern Zambia), 1976. Photo by Robert Cancel World Oral Literature Series: Volume 3 Storytelling in Northern Zambia: Theory, Method, Practice and Other Necessary Fictions Robert Cancel http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Robert Cancel. Foreword © 2013 Mark Turin. This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license (CC-BY 3.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made the respective authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Further details available at http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Attribution should include the following information: Cancel, Robert. Storytelling in Northern Zambia: Theory, Method, Practice and Other Necessary Fictions. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2013. This is the third volume in the World Oral Literature Series, published in association with the World Oral Literature Project. World Oral Literature Series: ISSN: 2050-7933 Digital material and resources associated with this volume are hosted by the World Oral Literature Project (http://www.oralliterature.org/collections/rcancel001.html) and Open Book Publishers (http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254596). ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-60-2 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-59-6 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-61-9 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-62-6 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-63-3 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0033 Cover image: Mr. -

A Study of Illocutionary Acts in Heroes Series

A STUDY OF ILLOCUTIONARY ACTS IN HEROES SERIES Achmad Nurdiansyah English Department, Faculty of Languages and Arts, State University of Surabaya Email:[email protected] Abstrak Sewaktu menyaksikan sebuah film atau serial televisi, orang-orang secara tak sadar mengamati sebuah aktivitas sosial berupa komunikasi antar para pemeran. Dengan meneliti sebuah serial televisi Amerika berjudul Heroes, peneliti berusaha mengadakan studi tentang tipe-tipe tindak tutur ilokusi beserta fungsi sosial dalam komunikasi melalui dialog di serial tersebut. Untuk mengidentifikasi tipe-tipe dan subtipe tindak tutur ilokusi dalam dialog, beberapa teori yang dicetuskan oleh Searle dalam Yule (1996) dan Bach & Harnish (1982) digunakan untuk penelitian ini, sementara teori fungsi sosial dalam tindak tutur ilokusi yang digagas oleh Leech (1983) digunakan sebagai landasan untuk mengidentifikasi fungsi sosial dari tipe-tipe tindak tutur ilokusi. Penelitian ini juga berusaha membuktikan bahwa tindak tutur representatif merupakan tipe ilokusi paling dominan dalam sebuah serial sebagaimana dalam sebuah film, serta mencermati pengaruhnya terhadap cerita di serial ini. Hasil pertama dari penelitian ini mendapati bahwa kelima tipe tindak tutur ilokusi ditemukan dalam naskah serial Heroes dengan 6351 temuan yang teridentifikasi sebagai ungkapan tindak tutur ilokusi, dengan kelima tipe tersebut adalah komisif, deklarasi, direktif, ekspresif dan representatif. Kedua, peran tindak tutur ilokusi sebagai fungsi sosial dalam serial ini dipengaruhi oleh gaya -

Blood Music" Appeared in ANALOG

A Warner Communcahons Company Copyright © 1989 by Greg Bear All rights reserved. Warner Books, Inc., 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10103 OA Warner Communications Contpany Printed in the United States of America First Pnnting: August 1989 1098765432 I Library of Congress Cataloging-m-Publication Data Bear, Greg, 1951- Taugents / Greg Bear. p. crli. ISBN 0-446-51401-2 I. Title. 88-40597 PS3552.EI57T3 1989 CIP 813'.54--4c20 Book Design by Nick Mazzella ACKNOWLEDGMENTS "Blood Music" appeared in ANALOG. Copyright © 1983 by Oreg Bear. "Sleepside Story" was originally published by Cheap Street Press in a limited edition in 1988. Copyright © 1988 by Greg Bear. "Webster" appeared in ALTERNITIES, edited by David Gerrold. Copyright © 1973 by Greg Bear. "A Martian Ricorso" appeared in ANALOG. Copyright © 1976 by Greg Bear. "Dead Run" appeared in OMNI. Copyright © 1985 by Greg Bear. Schrodmger s Plague" appeared in ANALOG. Copyright 1982 by Greg Bear. "Through Road No Whither" appeared in FAR FRONTIERS, edited by Jerry Poumelle and Jim Baen. Copyright © 1985 by Greg Bear. "Tangents" appeared in OMNI. Copyright © 1986 by Greg Bear. "Sisters" appears in this anthology for the first time. Copyright © 1989 by Greg Bear. "The Machineries of Joy" was first published by the Nesfa Press in EARLY HARVEST Copyright © 1987 by Greg Bear. This book is for Erik More wonderful by far than anything contained herein. CONTENTS Introduction · 3 Blood Music · 11 Sleepside Story · 45 Webster · 101 A Martian Ricorso · 121 Dead Run · 145 Schr(Sdinger's Plague · 181 Through Road No Whither · 195 Tangents · 203 Sisters · 227 Introduction to "The Machineries of Ja The Machineries of Joy · 270 ,y" · 269 INTRODUCTION W at is so fascinating about science fiction? Why o so many feel an attraction to its subjects, and a persistent few continue to think of it as (on the whole) worthless garbage? The answer, I think, lies in a basic American dichotomy. -

On Becoming a Leader.Pdf

0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page i More praise for On Becoming a Leader “Warren Bennis—master practitioner, researcher, and theoretician all in one—has managed to create a practical primer for leaders without sacrificing an iota of necessary subtlety and complexity. No topic is more important; no more able and caring person has attacked it.” —Tom Peters “The lessons here are crisp and persuasive.” —Fortune “This is Warren Bennis’s most important book.” —Peter Drucker “A joy to read...studded with gems of insight.” —Dallas Times-Herald “Bennis identifies the key ingredients of leadership success and offers a game plan for cultivating those qualities.” —Success “Clearly Bennis’s best work in a long line of impressive, significant contributions.” —Business Forum “Totally intriguing, thought-stretching insights into the clockworks of leaders. Bennis has masterfully peeled the onion to reveal the heartseed of leadership. Read it and reap.” —Harvey B. McKay “Warren Bennis gets to the heart of leadership, to the essence of integrity, authenticity, and vision that can never be pinned down to a manipulative formula. This book can help any of us select the new leaders we so urgently need.” —Betty Friedan “Warren Bennis’s insight and his gift with words make these lessons, from some of America’s most interesting leaders, compelling reading for every executive.” —Charles Handy 0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page ii This page intentionally left blank 0465014088_fm.qxd:0738208175_fm.qxd 12/2/08 2:52 PM Page -

Created by Prodigious Heroes Jumpchain Welcome to the World of Heroes

Created by Prodigious Heroes jumpchain Welcome to the world of heroes. Despite what the title may suggest, there's no running around in tights and capes. What they do have a lot of is powers. Besides these few powered families, the world functions more or less as normal. This can be attributed to 'The Company'. A department dedicated to making sure the existence of these people isn't discovered. Even if it requires a little memory wiping. Save the cheerleader, save the world. You are given +1000CP Location Roll a D8 for location or pay 100CP to choose 1. Odessa, Texas: Home of the Bennets and Primatech, your generic paper Company. 2. New York City: The big apple. Home to the Petrelli family. 3. Tokyo: The starting place of Hiro and Ando. Yamagato Industries is based here. 4. Santo Domingo: Home of Maya and Alejandro Herrera. 5. Madras, India: The former home of DrSuresh, and current home of Sanjog Lyer. 6. New Orleans: Home of the Dawsons, family to the Sanders. 7. Port-au-Prince, Haiti: Home of, you gussed it, the Haitian. 8. Free pick: Anywhere on earth. Background Age is 2D8+10 Gender is the same as before Pick both for 100CP Drop in - Free You find yourself taking a leisurely walk in whatever location you selected. You can't remember starting the walk, or where you were heading. You should probably look for somewhere to stay. + No memories besides your own - Nothing in this world to help you Citizen - 100 You're an average citizen of your starting area. -

Super Who? Super You! Week Two Day Five: Quick on the Draw!

Super Who? Super You! Week Two Day Five: Quick on the Draw! A great resource for kids and teachers for this section is: So, You Want to Be a Comic Book Artist?: The Ultimate Guide on How to Break ... By Philip Amara Think of the comics you enjoy. What is it you enjoy about them? Getting started with comics is just about finding something to draw with and something to draw on. Challenge students into telling a story in three to six panels. As they grow more comfortable with these single page strips they can start moving on to longer stories. One way to start is by trying to depict something that happened to you today in your own life. At home, at school, on the bus. Just keep it short. Jot down a few ideas, a few lines. Don’t get caught up thinking there are any right or wrong ways to making a comic because there aren’t. Simply tell a story, draw it in pictures, and place it in a sequence. Because much of the comic book story can be told through the characters’ expressions and body language, your characters’ conversations can be brief and to the point. Since you don’t need a lot of it, the dialogue should be interesting, tell you something about the characters, and move the plot forward. You can use sound effects (also called onomatopoeia) to help tell your story and what’s happening too. Think about how to use your characters to best tell the story. Using one of your completed scripts or story prompts, draw a rough, quick sketch to correspond with each panel in your script. -

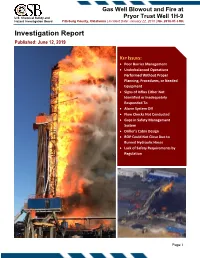

Pryor Trust Final Investigation Report

Gas Well Blowout and Fire at U.S. Chemical Safety and Pryor Trust Well 1H-9 Hazard Investigation Board Pittsburg County, Oklahoma | Incident Date: January 22, 2018 | No. 2018-01-I-OK Investigation Report Published: June 12, 2019 KEY ISSUES: • Poor Barrier Management • Underbalanced Operations Performed Without Proper Planning, Procedures, or Needed Equipment • Signs of Influx Either Not Identified or Inadequately Responded To • Alarm System Off • Flow Checks Not Conducted • Gaps in Safety Management System • Driller’s Cabin Design • BOP Could Not Close Due to Burned Hydraulic Hoses • Lack of Safety Requirements by Regulation Page 1 Gas Well Blowout and Fire at U.S. Chemical Safety and Pryor Trust Well 1H-9 Hazard Investigation Board Pittsburg County, Oklahoma | Incident Date: January 22, 2018 | No. 2018-01-I-OK The U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CSB) is an independent Federal agency whose mission is to drive chemical safety change through independent investigations to protect people and the environment. The CSB is a scientific investigative organization, not an enforcement or regulatory body. Established by the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, the CSB is responsible for determining accident causes, issuing safety recommendations, studying chemical safety issues, and evaluating the effectiveness of other government agencies involved in chemical safety. More information about the CSB is available at www.csb.gov. The CSB makes public its actions and decisions through investigative publications, all of which may include safety recommendations when appropriate. Types of publications include: Investigation Reports: formal, detailed reports on significant chemical incidents that include key findings, root causes, and safety recommendations.