Mb 1525 Will Be Closed Thursday, September 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2007 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol

september 2007 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVIII, No. 4 XLVIII, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published Edition Moeck 2825 Celle · Germany Tel. +49-5141-8853-0 www.moeck.com NEW FROM MAGNAMUSIC American Songs Full of Songs Spirit & Delight Fifteen pieces For TTB/SST freely arranged for The twenty lovely recorder trio, SAT, pieces in this by Andrew aptly named set Charlton. Classics demonstrate why like America, Michael East in Battle Hymn of the his time was Republic, America arguably one of the Beautiful, The the most popular Caisson Song, of the Elizabethan Columbia, the Gem composers. of the Ocean, The Marines Hymn, Chester, Complete edition from the original score, with Battle Cry of Freedom, All Quiet along the intermediate difficulty. 3 volumes. $8.95 each Potomac, I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy, Vol. 1 ~ TTB Vol. 2 ~ TTB Vol. 3 ~ SST Marching through Georgia, and more! TR00059 TR00069 TR00061 Item No. JR00025 ~ $13.95 IN STOCK NOW! An inspiring and instructive guide for everyone who plays the recorder (beginner, intermediate, experienced) and wants to play more beautifully. The Recorder Book is written with warmth and humor while leading you in a natural, methodical way through all the finer points of recorder playing. From selecting a recorder to making it sing, from practicing effectively to playing ensemble, here is everything you need. This is a most enjoyable read, whether you are an amateur or an expert. The repertoire lists have been updated, out-of-print editions have been removed, and edition numbers have been changed to reflect the most recent edition numbering. -

Early Music Instruments on Permanent Loan to EMSQ from QUT Enquiries

Early Music Instruments on permanent loan to EMSQ from QUT Enquiries about hiring instruments should be directed to Michael Yelland - email [email protected], mobile 0404 072 209 Monthly Item Maker's marks EMSQ Code Comments rental Deposit Viols Bass viol Inside label "Geoff Wills Lota 1973" BV1 $30 $120 Bass viol Inside label "Geoff Wills 1979" BV2 $30 $120 Tenor viol Inside label "Geoff Wills 1980" TeV1 $30 $120 Treble viol Inside label "Geoff Wills 1983" TrV1 $30 $120 Treble viol Geoff Wills 1976 TrV2 $30 $120 Bass viol Geoff Wills BV3 $30 $120 Tenor viol Geoff Wills - no label TeV2 $30 $120 Bass viol Geoff Wills BV4 $30 $120 Sopranino recorders Sopranino recorder Aulos Snino1 $10 $40 Not available Sopranino recorder Aulos Snino2 $10 $40 Not available Descant recorders Descant recorder Moeck SR1 Renaissance style, three joints $20 $80 Not available Descant recorder Hohner SR2 Baroque style, plastic rings, three joints $20 $80 Descant recorder Hohner SR3 Baroque style, plastic rings, three joints $20 $80 Descant recorder Moeck SR4 Baroque style, ivory rings, three joints $20 $80 Descant recorder Dolmetsch SR5 Baroque style. TJ16572, MJ16572, TJBJ16577 $10 $40 Not available Treble recorders Treble recorder Dolmetsch AR1 Baroque style, ivory mouthpiece $20 $80 Treble recorder Hohner AR2 Plastic rings, has been recorked $20 $80 Treble recorder AR3 Plastic rings, has been recorked, chips off bottom Hohner joint $20 $80 Treble recorder Moeck AR4 Ivory rings $20 $80 Treble recordeer Moeck AR5 Renaissance style, brass rings, flared -

J a N U a R Y 2 0

January 2010 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. LI, No. 1 • www.americanrecorder.org NEW! Enjoy the recorder Denner great bass Mollenhauer & Friedrich von Huene “The Canta great bass is very intuitive to play, making it ideal for use in recorder “The new Mollenhauer Denner orchestras and can be great bass is captivating with recommended .” its round, solid sound, stable in every register. Its key mechanism Dietrich Schnabel is comfortable and especially (conductor of recor- well designed for small hands. An der orchestras) instrument highly recommended for both ensemble and orchestral playing.” Daniel Koschitzky Canta knick great bass (member of the ensemble Spark) Mollenhauer & Friedrich von Huene G# and Eb keys enable larger finger holes and thus an especially stable sound. The recorder case with many extras With adjustable support spike … saves an incredible amount of space with the two-part middle joint … place for music … integrated recorder stand Order-No. 2646K Order-No. 5606 www.mollenhauer.com A Care and Maintenance Manual Chapter 1 - Where It All For the Recorder Started • A Brief History Your Recorder, like a pet, can "purr like a well fed pussycat, or an uncontrollable • How It Works and unpredictable beast…" • The Birth of a Recorder "This book, like the late Barbara Woodhouse, will show you how to take your recorder on walkies in respectable society and still stand proud!" Chapter 2 - Basic Training • Keeping its coat shiny • Maintaining the inner pet – cleaning the bore. • Block Cleaning • Windway Cleaning • Block Replacement Chapter 3 - Advanced Training • Recorder Voicing • Looking and Seeing Chapter 4 - Really Major Surgery • The Windway • The Labium Chapter 5 - Tuning the bore and finger holes • DYI Tuning • Diagrams for note, finger and pitch influence, bore diameter and pitch. -

Recorders & More

Enjoy the recorder New Models Denner Alto Denner-Edition Alto 442/415 Denner-Line Alto 415 Denner Bass Cap Dream-Edition Recorders & more for beginners to professional players Recorders Accessories Recorder Clinic Recorder-World Museum, Seminars www.mollenhauer.com Useful information / Maintenance / Oiling Editorial Enjoy the Recorder Come on in … “Mollenhauer Recorders” is more than just a workshop. It is a lively meeting point for performers of every age, from hobby- ists to pros, from all around the world. Over the years, many thousands of recorder players have visited our workshops, our Recorder-World Museum and our seminars! Our journal, “Windkanal”, is a well-known and respected forum presenting the colourful world of the recorder in all its diversity. Our website is a valuable resource for information about the recor- der and is used by friends of the recorder the world over. Ours is an open workshop. We strive to bring you the fascinat- ing world of recorder making while at the same time entering into a dialogue with you – about our instruments, about ideas, about visions … Communication at a personal level is important to us. Part- nership and cooperation are central to how we operate ... not only within our own team: we welcome your questions! Since we see cooperation and innovation as being very closely related, we seek out and form partnerships with especially cre- ative people such as recorder makers Maarten Helder, Friedrich von Huene, Adriana Breukink, Nik Tarasov and Joachim Paetzold. Furthermore, we consider each and every recorder player, teacher and music dealer that shares with us their experiences and ideas – thus sharing in the further development of our instruments as well – to be our partners. -

Sound Sets in Sibelius 2

Sound sets in Sibelius 2 For advanced users only! Before attempting to create your own sound set, it is worth checking if one is already available: see the online Help Center at http://www.sibelius.com/helpcenter/resources/ for the latest additions. Disclaimer Sound sets are complex files and are not designed to be user-editable. Using a sound set with incorrect syntax may cause your copy of Sibelius to behave unpredictably or even crash. Sibelius Software accepts no responsibility for any loss of data or other problems experienced as a result of editing the supplied sound sets or creating new ones. This document is provided ‘as is’, and no warranty, implied or otherwise, covers the information contained within. Please also note that we do not offer technical support on the editing or creation of sound set files. Filenames The filename of a sound set file is insignificant (i.e. it is not shown in the Play Z Devices dialog), but we recommend that it should be fairly descriptive. It should also be 31 characters or less (including the .txt file extension) to ensure compatibility with all file systems. Sound set syntax Please refer to the General MIDI.txt file inside C:\Program Files\Sibelius Software\Sibelius 2\Sounds for an example of correct sound set syntax. In fact, you may wish to copy this file and use it as the basis of your own sound set. The sound set starts with an open brace { and ends with a closing brace }. The body of the sound set contains the following fields within the opening and closing braces as a series of ‘tree nodes’, in this order: MIDIDevice Syntax: MIDIDevice "GM (General MIDI)" The name of the device, e.g. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Recorder Syllabus Message from the President 3 Preface

recorder The Royal Conservatory of Music Official Examination Syllabus © Copyright 2008 The Frederick Harris Music Co., Limited All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-55440-224-3 Contents Message from the President ................. 3 www.rcmexaminations.org ................. 4 Preface................................. 4 REGISTER FOR AN EXAMINATION Examination Sessions and Registration Deadlines 5 Examination Centers ...................... 5 Online Registration . 5 Examination Scheduling ................... 6 Examination Fees ........................ 5 EXAMINATION REGULATIONS Examination Procedures ................... 7 Practical Examination Certificates ............ 13 Credits and Refunds for Missed Examinations... 7 School Credits........................... 14 Candidates with Special Needs .............. 8 Medals................................. 14 Examination Results ...................... 8 RESPs ................................. 15 Table of Marks......................... 9 Examination Repertoire.................... 15 Theory Examinations ..................... 10 Substitutions ............................ 17 ARCT Examinations ...................... 12 Abbreviations ........................... 18 Supplemental Examinations ................ 12 Thematic Catalogs........................ 19 Musicianship Examinations................. 13 GRADE-BY-GRADE REQUIREMENTS Technical Requirements.................... 20 Grade 8 ................................ 43 Grade 1 ................................ 23 Grade 9 ................................ 49 Grade 2 -

Fipple Flutes Fipple Flutes Are End-Blown Flutes That Produce Sound Through the Use of a Constricted Mouthpiece

Fipple Flutes Fipple flutes are end-blown flutes that produce sound through the use of a constricted mouthpiece. Contained within the mouthpiece is a device, known as a fipple, that splits the air stream and produces the sound. Fipple flutes are generally played in a vertical position and include such instruments as the tin whistle, the recorder and the slide whistle. Recorder A popular instrument from the Middle Ages through the Baroque period, the recorder family has enjoyed renewed interest during recent times. The timbre of the recorder is wonderfully pure, clear, and somewhat more innocent sounding than the flute. The instrument has a limited dynamic range and is not capable of producing loud dynamic levels. As such, it is best used in a chamber music or soloistic setting. It is manufactured in a variety of sizes/registers ranging from the sopranino recorder, down to the double contrabass recorder. In addition to its usage in the concert environment, recorders can be quite effective when used in film and television documentary scores, evoking either a genre-specific timbre, or a sense of childhood. For small recorder ensembles, individual parts are not required, as players are comfortable reading from a score. For larger ensembles (a quintet or larger) involving lower bass clef instruments, individual (transposed) parts are required. Sopranino Recorder The smallest and highest register member of the recorder family, the sopranino recorder is the piccolo of the recorder family. It does not blend as well as the rest of the recorder family and is best used for accentuating selected melodic lines, obbligato figures, and for “splashes” of color. -

N O V E M B E R 2 0

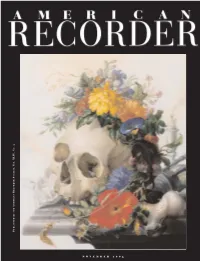

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLIV, No. 5 november 2003 A Flanders Recorder Quartet Guide for Recorder Players and Teachers BART SPANHOVE With a historical Chapter by DAVID LASOCKI The purpose of this book is to help recorder players become better ensemble members. Bart Spanhove has written the book in response to numerous requests from both amateurs and professionals to set down some practical suggestions based on his own experience and thereby fill a long-felt gap in the literature Alamire Music Publishers about the recorder. Toekomstlaan 5B, BE-3910 Neerpelt Price: 22,06 Euro T. +32 11 610 510 Orders can be placed at F. +32 11 610 511 www.alamire.com [email protected] EDITOR’S ______NOTE ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume XLIV, Number 5 November 2003 Death and music are no strangers. FEATURES Death is often found in operatic context— A Recorder Icon Interviewed . 8 the tragic ending in Giacomo Puccini’s A Talk with Anthony Rowland-Jones, Tosca when the title figure leaps to her by Sue Groskreutz death, and the stirring music composed by The Recorder in the Nineteenth Century. 16 Richard Wagner for Siegfried’s funeral near by Douglas MacMillan the end of the four-part epic Ring cycle, af- 4 Arranging an Orchestral Work for Recorder Quintet . 22 ter which Brunhilde flings herself on the The eleventh in a series of articles by composers and arrangers hero’s funeral pyre and sings for another discussing how they write and arrange music for recorder, 10 minutes or so. by Carolyn Peskin Death’s knock shows up in Tchaikovsky’s symphonies and, under- scoring the underlying sorrow of war, in DEPARTMENTS the theme song from M*A*S*H—titled Advertiser Index . -

Daily Recorder Exercises

Daily Recorder Exercises by Peter Billam forBass Recorder ©Peter J Billam, 1995 This score is offered under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence; see creativecommons.org This printing 15 February 2014. www.pjb.com.au Daily Recorder Exercises The first twopages of these exercises date from 1995, when I was a tutor in the Recorder ’95 festivalinMelbourne. Whyshould recorder players practice in remote keys likeF#major ? Because in almost every piece in B minor,and hence eveninDmajor, there is some passage in the dominant, in this case F# major,and unless the player has practised in this key,that passage is always the one which spoils the whole movement. The third page, of minor arpeggios, was added recently because I noticed that while sight-reading I was playing the major arpeggios with greater fluencythan minor ones. Systematic technical exercises such as these are less used by recorder players than other instrumentalists, but theyare very effectice in generating a maximum of fluencyfrom a minimum of playing time. Theyshould be used regularly every day; ten minutes a day is farsuperior to one hour per week. The goal when practising should be to let each note sing strongly and sweetly right from its very first moment to its very last, and then to change cleanly into the next note, with the tongue and all the fingers moving simultaneously so that no ugly scrunching sounds mar the transition. As the transitions become flawless, the sweet singing line will begin to join up from note to note, and develops into a large thing which has its own identity and beauty. -

Recorders and Electronics

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright RECORDERS AND ELECTRONICS: An Introduction to the Performance of Electroacoustic Music Joanne Arnott A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2014 ii iii Abstract The development of the electroacoustic genre has presented modern recorder players with a myriad of new and exciting repertoire, but many acoustic musicians are reluctant to explore these new works due to the barriers of technology. -

Notes on "Three Bassoons" in the National Museum of Antiquitie Scotlandf So Lyndesay B

IV. NOTES ON "THREE BASSOONS" IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIE SCOTLANDF SO LYNDESAY B . LANGWILLYG , C.A. On inspection, these old instruments are found to be two Bassoons an d"a Bass Recorder " r " Baso s FKite Douce. followine Th " g description, considered in conjunction with the illustrations showing both the back and the front of the instruments, will enable us to form a fairly accurate thesf o e eestimat ag exhibits e th f eo . The Bassoon (Fr. Basson, Span. Bajon, German Fagott, Ital. Fagotto) is the modern survival of the German Bass-Pommer of the sixteenth cen- tury, having evolved throug intermediare hth y form know Dulziane th s na . distinguishine Th g feature modere th f so conica ne bassooth ) (1 l e tubnar e ofeet8 f , doubled bac U-fashion ki r conveniencnfo f handlingeo e th ) (2 , sound-producing medium—a large double-reed, and (3) the bent S-shaped metal " crook whic o "t reee firss haffixedth s d i wa t t introduceI . d into e orchestrth a circa f comparisono y 167 Lullyy wa 4 b y B a moder., n orchestral 20-keyed "Buffet" bassoon (French) is shown alongside the Museum exhibits (fig. 1 (a) and fig. 2 (a)). While it is unfortunate that we know nothing of the history of these bassoonso tw s possibli t ,i e they wer locan ei e Citl th f Edinus yo n i e - burgh. Sir John Dalyell in his scholarly Musical Memoirs of Scotland e "doublth f (1849)o e . 163p us ,curtle ,e refer th n "th i "o t se good toune's music Edinburgn i " 1696n hi , when John Munro Malcold ean m McGibbon were found "compleat masters of playing upon the French hautboyes and double curtle." (Edinburgh Town Council Register, vol.