A Negotiation Analysis of the Dabhol Power Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cover 1 the Enron Story

Cover 1 The Enron Story: Controversial Issues and People s Struggle Contents Preface I. The Project and the First Power Purchase Agreement II. Techno-economic and Environmental Objections III. Local People“s Concerns and Objections IV. Grassroots Resistance, Cancellation of the Project and It“s Revival V. The Renegotiated Enron Deal and Resurgence of Grassroots Resistance VI. Battle in the Court VII. Alternatives to Enron Project Conclusions Appendices I Debate on Techno-economic objections II The Merits of the Renegotiated Project III Excerpts from the Reports of Amnesty International IV Chronology of Events Glossary The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 Cover 3 Cover 4 The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 (PRAYAS Monograph Series) The Enron Story: Controversial Issues and People s Struggle Dr. Subodh Wagle PRAYAS Amrita Clinic, Athavale Corner Karve Road Corner, Deccan Gymkhana Pune, 411-004, India. Phone: (91) (212) 341230 Fax: (91) (212) 331250 (Attn: # 341230) PRAYAS Printed At: The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 For Private Circulation Only Requested Contribution: Rs. 15/- The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 Preface cite every source on every occasion in such a brief monograph. But I am indebted for the direct and indirect help from many The Enron controversy has at least four major categories individuals (and their works) including, Sulbha Brahme, Winin of issues: techno-economic, environmental, social, and legal or Pereira and his INDRANET group, Samaj Vidnyan Academy, procedural. In the past, the Prayas Energy Group has concentrated Abhay Mehta, and many activists especially, Yeshwant Bait, its efforts mainly on the techno-economic issues. Many Ashok Kadam, and Arun and Vijay Joglekar. -

Request for Arbitration

REQUEST FOR ARBITRATION UNDER THE INVESTMENT INCENTIVE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 19 NOVEMBER 1997 - BETWEEN - THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (Claimant) THE GOVER1NMENT OF INDIA 0~espondent) November 4, 2004 UNDER THE INVESTMENT INCENTIVE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND TIRE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ) Govermnent of tile ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) c/o Office of the Legal Adviser ) U.S. Department of State ) Washington, D.C. 20520 ) United States of America ) ) Claimant, ) ) and ) ) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ) Honorable Mamnohan Singh ) Prime Minister ) c/o Ministry of External Affairs ) South Block ) New Delhi 110001 ) Republic of India ) ) Respondent. ) ) REQUEST FOR ARBITRATION 1. Pursuant to Article 6 of the Investment Incentive Agreement ("Bilateral Agreement" or "Agreement")t between the Govenwaent of tbe United States of America and the Government ~ Signed on November 19, 1997 and entered into force on April 16, 1998. A copy of the Bilateral Agreement is atlached hereto as Exhibit 1. Article 7(a) of the Bilateral Agreement provides that the Bilateral Agreement shall "replace and supersede the agreement between the United States of America and India on the Guaranty of Private Investments effected by exchange of notes signed at Washington on September 19, 1957 as supplemented by exchanges of notes signed at Washington on December 7, 1959 and at New Delhi on February 2, 1966 (the ’Prior Agreement’)." Article 7(a) further provides that any matter related to Investment Support provided under the Prior Agreement shall be resolved under the Bilateral Agreement, unless raised prior to entry into force of the Bilateral Agreement. -

Exploring Corruption in Public Financial Management 267 William Dorotinsky and Shilpa Pradhan

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 39985 The Many Faces of Corruption The Many Faces of Corruption Tracking Vulnerabilities at the Sector Level EDITED BY J. Edgardo Campos Sanjay Pradhan Washington, D.C. © 2007 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 2 3 4 5 10 09 08 07 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Konkan LNG Private Limited (KLPL), Dabhol ------RFQ/ Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 Dated 01.08.2019

Konkan LNG Private Limited (KLPL), Dabhol ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RFQ/ Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 dated 01.08.2019 BIDDING DOCUMENT FOR Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of 24 months. TENDERING UNDER “DOMESTIC COMPETITIVE BIDDING” Prepared and Issued by Konkan LNG Private Limited At & Post Anjanwel, Tal-Guhagar Dist.: Ratnagiri Maharashtra-415634 Ph. No. : 02359-241015 BID/OFFER/TENDER IS TO BE SUBMITTED AT BELOW ADDRESS THROUGH REGD.POST / COURIER:- HOD (C&P), Konkan LNG Private Limited At & Post Anjanwel, Tal-Guhagar Dist.: Ratnagiri Maharashtra-415634 Ph. No. : 02359-241015 Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 for Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of Two years Page 1 of 162 SECTION-I INVITATION FOR BID (IFB) Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 for Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of Two years. Page 2 of 162 SECTION-I "INVITATION FOR BID (IFB)” Ref No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 Date: 01.08.2019 To, PROSPECTIVE BIDDERS SUB: TENDER DOCUMENT FOR Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of 24 months. Dear Sir/Madam, 1.0 Konkan LNG Pvt. Limited, promoted by M/s GAIL (India) Limited & M/s NTPC Limited, having registered office at 16, Bhikaji Cama Place, New Delhi 110066 & CIN No. -

Electricity in India

prepa india 21/02/02 12:14 Page 1 INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY ELECTRICITY IN INDIA Providing Power for the Millions INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY ELECTRICITY IN INDIA Providing Power for the Millions INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION FOR ENERGY AGENCY ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION 9, rue de la Fédération, AND DEVELOPMENT 75739 Paris, cedex 15, France The International Energy Agency (IEA) is an Pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention signed in autonomous body which was established in Paris on 14th December 1960, and which came November 1974 within the framework of the into force on 30th September 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to implement an Development (OECD) shall promote policies international energy programme. designed: It carries out a comprehensive programme of • To achieve the highest sustainable economic energy co-operation among twenty-six* of the growth and employment and a rising standard OECD’s thirty Member countries. The of living in Member countries, while maintaining basic aims of the IEA are: financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy; • To maintain and improve systems for coping • To contribute to sound economic expansion in with oil supply disruptions; Member as well as non-member countries in • To promote rational energy policies in a global the process of economic development; and context through co-operative relations with • To contribute to the expansion of world trade non-member countries, industry and on -

2020052639.Pdf

'-• DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT RATNAGIRI DISTRICT FOR SAND MINING OR RIVER BED SAND MINING: .. Prepared under " A) Appendix -X of MOEFCC, GOI Notification S.O 141(E) dated 15/0112016 •_, B) Sustaniable Sand Mining Guideliness C) MOEFCC, GOI,Notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25/07/2018 (2019-2020) Prepared By District Mining Officer, Collector Officer, Ratnagiri Declaration In compliance to the notification, guidelines issued by Ministry if Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, New Delhi, District Survey Re'port for Ratnagiri district is prepared and published. Place : Ratnagiri Date: 29/03/2019 • •.. • .. • • • • MAP OF RATNAGIRI DISTRICT: • • MAr (,f • RAINAGIRI tR" 1 nrs AOMINISTRAllli1 ">n UP • "l" • • '" • • 17" • 30' • ~ .. • 17' is' A • N • • .. • • 16" • S' • INOEX DISTlI'ICl BOUHCAIh' • ,. DISTRICT ...,.;.oQUAAT&:N TAi..I..IKA BOtl"O~Y • ... ',"-UK'" HlAO~- • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • OBJECTIVE:- • The main objective of the preparation of District Survey Report (as per the • 'Sustainable Sand Mining Guideline) is to ensure the following: • Identification of the areas of aggradations or deposition where mining can be • allowed and identification of areas of erosion and proximity to infrastructural structures and installation where mining should be prohibited and calculation of annual rate of replenishment • and allowing time for replenishment after mining in the area. • • 1.0 Introduction: • Whereas by notification of the Government of India in erstwhile Ministry of Environment, • Forest issued vide number S.O. 1533 (E),dated the 14 th September,2006 published in the • Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II ,Section 3, Subsection (ii)(hereafter referred to as the • said notification) directions have been given regarding the prior environment clearance; and whereas, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has amended the said • notification vide S.O. -

Sno Name Shareholder's Address Unpaid Dividend Amount 1 Chetan

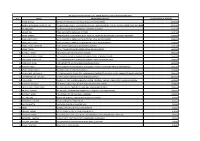

Dil_Unpaid dividend details as on 25 Feb,2021 For Interim Dividend 2020-2021 Sno Name Shareholder's Address Unpaid Dividend Amount 1 Chetan Burman 4th Floor, Punjabi Bhawan10, Rouse Avenue New Delhi110002 48562.00 2 WORTH WHILE PORTFOLIOS PVT LTD C/O BAIDYANATH B-6/5 , SAFDURJUNG ENCLAVE , LOCAL SHOPPING CENTRE, OPP DEER PARK NEAR HDFC BANK BUILDING, NEW DELHII110029 19425.00 3 RAHIMUDDIN . RAZAPUR GHAZIABAD GHAZIABAD UTTAR PRADESH201002 19425.00 4 JAI RAM DAS TERHI GALI CHOWK FAIZABAD UP224001 16187.00 5 SINGH SHARAD PRABHA DENTAL CLINIC BEHIND GOVT HOSPITAL KALAPURA RD SHEOGANJ DIST SIROHI RAJ307027 21000.00 6 SUSHILABEN J SHAH 503-A DALAMAL CHAMBERS,17,NEW MARINE LINES, MUMBAI400020 16800.00 7 SUSHILABEN J SHAH 503-A DALAMAL CHAMBERS,17,NEW MARINE LINES, MUMBAI400020 21000.00 8 CEDRIC SOUZA CORDEIRO H NO 1096NIGUADDO SALIGAO BARDEZ GOA403511 11331.00 9 VEENA TIWARI C/O V K TIWARI 202 GANGA SAGAR GARHA JABALPUR482003 16800.00 10 GURMEET SINGH P O KANCHILI DIST SRI KAKULAM A P532290 28000.00 11 CHAURASIA DHRU CHAND C/O. PRAKASH TRADERS, MAIN ROAD, BARHALGANJ, GORAKHPUR (UP)0 17500.00 12 CHAURASIA CHANDI LAL C/O. PRAKASH TRADERS, MAIN ROAD, BARHAL GANJ, GORAKHPUR (UP)0 17500.00 13 NARENDRA SINGH H NO 167 SECTOR 11 VASUNDHARAGHAZIABAD201010 16800.00 14 AJAY PAL SINGH SHRI PARSWANATH EYE HOSPITAL BEHIND GOVT HOSPITAL KALAPURA ROAD SHEOGANJ307027 16187.00 15 SINGH SUNIL KUMAR KALAPURA ROAD SHEOGANJ RAJ307027 12600.00 16 MURLI DHAR DHYAWALA C/O PARSHWANATH FINANCEE-4 PARASMANI APPARTMENT JAWAHAR CHOWK SABARMATI AHMEDABAD380005 16800.00 17 JAYSHREE DENISH KANJARIA 11 KIRTI COLONY USHMANPURA AHMEDABAD380013 42000.00 18 HIREN RADIA ANANTA A-3, 3RD FLOORRAJABALIPATEL ROAD , OPPOSITE . -

PDF File with Dabhol Case Write-Up from Indian Perspective Including

Dabhol Power Company11 Introduction In April 2003, power cuts and rolling blackouts were becoming regular occurrences in western India, and yet the ~$3 billion 2184 MW Dabhol Power Project in India’s western coast lay idle; after having been shut down for close to two years (~ 22 months). The impasse related to the project is amply reflected in the headlines of two Indian financial dailies, Business Standard &The Economic Times on April 4th, 2003. Foreign Lenders Want to End Dabhol PactPact (Business(Business StandardStandard – AprilApril 44thth)) Slow progress in project restructuring forces lenders to take decision In a major blow to efforts by the domestic lenders to restart the first phase of the Dabhol power project, overseas lenders to the project have expressed their intention to terminate the power purchase agreement (PPA) with the Maharashtra State Electricity Board (MSEB). FII Lenders to Terminate Dabhol PPA (The Economic Times – AprilApril 44thth)) A face-off between the offshore lenders and domestic lenders of Dabhol Power Company is now imminent. Even as discussions were on to restart phase-I of DPC, the foreign lenders have decided to terminate the power purchase agreement with MSEB. The Dabhol Power Project was originally conceptualised in 1992 as a show case project for India & for Enron (the main project sponsor). The project, which was identified as a fast-track project by the Government of India (GoI), was the largest gas based independent power project in the world and was also the largest foreign direct investment into India. It was also Enron’s largest power venture. Yet more than a decade later, the project, which is almost fully constructed and was partially operational, has run into numerous disputes among the various counter- parties and is on the verge of being junked. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Ratnagiri District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Ratnagiri District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute, Mumbai (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) Kurla Andheri Road, Saki Naka, Mumbai – 400 072. Phone: 022-28576090/28573091 Fax: 022-28578092 E-mail: [email protected] Web: msmedimumbai.gov.in Contents S. Topic Page No. No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals 3 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2.0 District at a glance 5 2.1 Existing status of Industrial Area in the District Ratnagiri 7 3.0 Industrial Scenario of Ratnagiri 7 3.1 Industry at Glance 7 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 8 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units in the 8 District 3.4 Large scale industries/Public sector undertakings 9 3.5 Major exportable items 9 3.6 Growth trend 9 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 9 3.8 Medium scale enterprises 10 3.8.1 List of the units in Ratnagiri & nearby areas 10 3.8.2 Major exportable items 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potential areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 12-13 4.0 Existing clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing sector 13 4.1.2 Service sector 13 4.2 Details of identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Mango Processing Cluster 14 5.0 General issues raised by Industries Association during the course of 14 meeting 6.0 Steps to set up MSMEs 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Ratnagiri District 1. -

School Wise Result Statistics Report

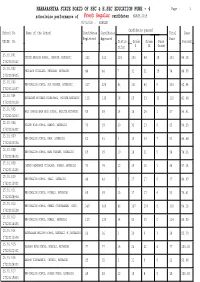

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 313 313 115 103 68 15 301 96.16 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 84 84 7 31 21 15 74 88.09 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 327 326 83 131 83 6 303 92.94 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 135 135 16 29 33 32 110 81.48 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 59 59 14 18 24 1 57 96.61 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 69 20 32 13 0 65 94.20 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 62 61 3 10 33 7 53 86.88 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 69 69 10 18 21 5 54 78.26 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 70 70 12 39 16 1 68 97.14 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 44 44 3 17 17 0 37 84.09 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 69 69 15 17 17 4 53 76.81 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 360 360 86 147 100 6 339 94.16 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 120 120 34 50 30 0 114 95.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 3 14 4 3 24 92.30 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 77 77 14 26 31 6 77 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 25 25 3 11 9 0 23 92.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 39 39 12 19 8 0 39 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

Chapter V the Monetary System and Taxation in Adil Shahi Sultanate

Chapter V The Monetary System and Taxation in Adil Shahi Sultanate The main focus of this chapter is particularly on the Monetary System and Taxation, however it also attemps to find out Prices of various commodities and the salaries and wages of various services during the period of the study. An attempt has been made here to study; how money was provided in the economy of the kingdom through the institutions like mints, money and coinage, and finance was made available for the expenditure of state by imposing agricultural and non-agricultural taxes and custom duties. An endeavor is also made here to study how the prices of the commodities, salary and wages of various services were determined by manufacturing cost, market place, competition, market condition, quality of product. 1. Monetary System 1.1 Coinage The discovery of coins associated with the remains of the early civilization is often cited as proof of the marketing systems. Coinage is viewed as the “consequence of the demand of market network that has evolved beyond previous localized commodity exchange. While earlier, localized exchange, was largely an extension of a reciprocity-based community, the use of coins implies less personalized marketplace, transactions and likely exchange with external economic agents. However, scholars have recently challenged this assertion by demonstrating that gold and silver coinage initially had prestige value in early societies, and might be used, especially in the case 207 of large-unit gold and silver coins in condition of reciprocity rather than market exchanges.”462 The coins belong to first four Adil Shahi rulers have not been found; hence it is believed that the Sultans preceding Ali Adil Shah I had not issued coins of their own.