Chapter V the Monetary System and Taxation in Adil Shahi Sultanate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cover 1 the Enron Story

Cover 1 The Enron Story: Controversial Issues and People s Struggle Contents Preface I. The Project and the First Power Purchase Agreement II. Techno-economic and Environmental Objections III. Local People“s Concerns and Objections IV. Grassroots Resistance, Cancellation of the Project and It“s Revival V. The Renegotiated Enron Deal and Resurgence of Grassroots Resistance VI. Battle in the Court VII. Alternatives to Enron Project Conclusions Appendices I Debate on Techno-economic objections II The Merits of the Renegotiated Project III Excerpts from the Reports of Amnesty International IV Chronology of Events Glossary The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 Cover 3 Cover 4 The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 (PRAYAS Monograph Series) The Enron Story: Controversial Issues and People s Struggle Dr. Subodh Wagle PRAYAS Amrita Clinic, Athavale Corner Karve Road Corner, Deccan Gymkhana Pune, 411-004, India. Phone: (91) (212) 341230 Fax: (91) (212) 331250 (Attn: # 341230) PRAYAS Printed At: The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 For Private Circulation Only Requested Contribution: Rs. 15/- The Enron Story, Prayas, Sept. 1997 Preface cite every source on every occasion in such a brief monograph. But I am indebted for the direct and indirect help from many The Enron controversy has at least four major categories individuals (and their works) including, Sulbha Brahme, Winin of issues: techno-economic, environmental, social, and legal or Pereira and his INDRANET group, Samaj Vidnyan Academy, procedural. In the past, the Prayas Energy Group has concentrated Abhay Mehta, and many activists especially, Yeshwant Bait, its efforts mainly on the techno-economic issues. Many Ashok Kadam, and Arun and Vijay Joglekar. -

Konkan LNG Private Limited (KLPL), Dabhol ------RFQ/ Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 Dated 01.08.2019

Konkan LNG Private Limited (KLPL), Dabhol ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RFQ/ Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 dated 01.08.2019 BIDDING DOCUMENT FOR Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of 24 months. TENDERING UNDER “DOMESTIC COMPETITIVE BIDDING” Prepared and Issued by Konkan LNG Private Limited At & Post Anjanwel, Tal-Guhagar Dist.: Ratnagiri Maharashtra-415634 Ph. No. : 02359-241015 BID/OFFER/TENDER IS TO BE SUBMITTED AT BELOW ADDRESS THROUGH REGD.POST / COURIER:- HOD (C&P), Konkan LNG Private Limited At & Post Anjanwel, Tal-Guhagar Dist.: Ratnagiri Maharashtra-415634 Ph. No. : 02359-241015 Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 for Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of Two years Page 1 of 162 SECTION-I INVITATION FOR BID (IFB) Tender No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 for Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of Two years. Page 2 of 162 SECTION-I "INVITATION FOR BID (IFB)” Ref No: KLPL/C&P/INST/SFL011/33000011/2019-20 Date: 01.08.2019 To, PROSPECTIVE BIDDERS SUB: TENDER DOCUMENT FOR Hiring of AMC for Testing and Calibration of IR Gas Detectors in LNG terminal at KLPL for contract period of 24 months. Dear Sir/Madam, 1.0 Konkan LNG Pvt. Limited, promoted by M/s GAIL (India) Limited & M/s NTPC Limited, having registered office at 16, Bhikaji Cama Place, New Delhi 110066 & CIN No. -

2020052639.Pdf

'-• DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT RATNAGIRI DISTRICT FOR SAND MINING OR RIVER BED SAND MINING: .. Prepared under " A) Appendix -X of MOEFCC, GOI Notification S.O 141(E) dated 15/0112016 •_, B) Sustaniable Sand Mining Guideliness C) MOEFCC, GOI,Notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25/07/2018 (2019-2020) Prepared By District Mining Officer, Collector Officer, Ratnagiri Declaration In compliance to the notification, guidelines issued by Ministry if Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, New Delhi, District Survey Re'port for Ratnagiri district is prepared and published. Place : Ratnagiri Date: 29/03/2019 • •.. • .. • • • • MAP OF RATNAGIRI DISTRICT: • • MAr (,f • RAINAGIRI tR" 1 nrs AOMINISTRAllli1 ">n UP • "l" • • '" • • 17" • 30' • ~ .. • 17' is' A • N • • .. • • 16" • S' • INOEX DISTlI'ICl BOUHCAIh' • ,. DISTRICT ...,.;.oQUAAT&:N TAi..I..IKA BOtl"O~Y • ... ',"-UK'" HlAO~- • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • OBJECTIVE:- • The main objective of the preparation of District Survey Report (as per the • 'Sustainable Sand Mining Guideline) is to ensure the following: • Identification of the areas of aggradations or deposition where mining can be • allowed and identification of areas of erosion and proximity to infrastructural structures and installation where mining should be prohibited and calculation of annual rate of replenishment • and allowing time for replenishment after mining in the area. • • 1.0 Introduction: • Whereas by notification of the Government of India in erstwhile Ministry of Environment, • Forest issued vide number S.O. 1533 (E),dated the 14 th September,2006 published in the • Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II ,Section 3, Subsection (ii)(hereafter referred to as the • said notification) directions have been given regarding the prior environment clearance; and whereas, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has amended the said • notification vide S.O. -

PDF File with Dabhol Case Write-Up from Indian Perspective Including

Dabhol Power Company11 Introduction In April 2003, power cuts and rolling blackouts were becoming regular occurrences in western India, and yet the ~$3 billion 2184 MW Dabhol Power Project in India’s western coast lay idle; after having been shut down for close to two years (~ 22 months). The impasse related to the project is amply reflected in the headlines of two Indian financial dailies, Business Standard &The Economic Times on April 4th, 2003. Foreign Lenders Want to End Dabhol PactPact (Business(Business StandardStandard – AprilApril 44thth)) Slow progress in project restructuring forces lenders to take decision In a major blow to efforts by the domestic lenders to restart the first phase of the Dabhol power project, overseas lenders to the project have expressed their intention to terminate the power purchase agreement (PPA) with the Maharashtra State Electricity Board (MSEB). FII Lenders to Terminate Dabhol PPA (The Economic Times – AprilApril 44thth)) A face-off between the offshore lenders and domestic lenders of Dabhol Power Company is now imminent. Even as discussions were on to restart phase-I of DPC, the foreign lenders have decided to terminate the power purchase agreement with MSEB. The Dabhol Power Project was originally conceptualised in 1992 as a show case project for India & for Enron (the main project sponsor). The project, which was identified as a fast-track project by the Government of India (GoI), was the largest gas based independent power project in the world and was also the largest foreign direct investment into India. It was also Enron’s largest power venture. Yet more than a decade later, the project, which is almost fully constructed and was partially operational, has run into numerous disputes among the various counter- parties and is on the verge of being junked. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Ratnagiri District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Ratnagiri District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute, Mumbai (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) Kurla Andheri Road, Saki Naka, Mumbai – 400 072. Phone: 022-28576090/28573091 Fax: 022-28578092 E-mail: [email protected] Web: msmedimumbai.gov.in Contents S. Topic Page No. No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals 3 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2.0 District at a glance 5 2.1 Existing status of Industrial Area in the District Ratnagiri 7 3.0 Industrial Scenario of Ratnagiri 7 3.1 Industry at Glance 7 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 8 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units in the 8 District 3.4 Large scale industries/Public sector undertakings 9 3.5 Major exportable items 9 3.6 Growth trend 9 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 9 3.8 Medium scale enterprises 10 3.8.1 List of the units in Ratnagiri & nearby areas 10 3.8.2 Major exportable items 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potential areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 12-13 4.0 Existing clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing sector 13 4.1.2 Service sector 13 4.2 Details of identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Mango Processing Cluster 14 5.0 General issues raised by Industries Association during the course of 14 meeting 6.0 Steps to set up MSMEs 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Ratnagiri District 1. -

School Wise Result Statistics Report

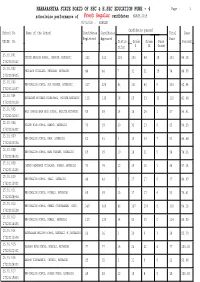

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 25.01.001 UNITED ENGLISH SCHOOL, CHIPLUN, RATNAGIRI 313 313 115 103 68 15 301 96.16 27320100143 25.01.002 SHIRGAON VIDYALAYA, SHIRGAON, RATNAGIRI 84 84 7 31 21 15 74 88.09 27320108405 25.01.003 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, A/P SAWARDE, RATNAGIRI 327 326 83 131 83 6 303 92.94 27320111507 25.01.004 PARANJAPE MOTIWALE HIGHSCHOOL, CHIPLUN,RATNAGIRI 135 135 16 29 33 32 110 81.48 27320100124 25.01.005 HAJI DAWOOD AMIN HIGH SCHOOL, KALUSTA,RATNAGIRI 59 59 14 18 24 1 57 96.61 27320100203 25.01.006 MILIND HIGH SCHOOL, RAMPUR, RATNAGIRI 70 69 20 32 13 0 65 94.20 27320106802 25.01.007 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, BHOM, RATNAGIRI 62 61 3 10 33 7 53 86.88 27320103004 25.01.008 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, MARG TAMHANE, RATNAGIRI 69 69 10 18 21 5 54 78.26 27320104602 25.01.009 JANATA MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KOKARE, RATNAGIRI 70 70 12 39 16 1 68 97.14 27320112406 25.01.010 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, OMALI, RATNAGIRI 44 44 3 17 17 0 37 84.09 27320113002 25.01.011 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, POPHALI, RATNAGIRI 69 69 15 17 17 4 53 76.81 27320108904 25.01.012 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KHERDI-CHINCHAGHARI (SATI), 360 360 86 147 100 6 339 94.16 27320101508 25.01.013 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, NIWALI, RATNAGIRI 120 120 34 50 30 0 114 95.00 27320114405 25.01.014 RATNASAGAR ENGLISH SCHOOL, DAHIWALI (B),RATNAGIRI 26 26 3 14 4 3 24 92.30 27320112604 25.01.015 DALAWAI HIGH SCHOOL, MIRJOLI, RATNAGIRI 77 77 14 26 31 6 77 100.00 27320102302 25.01.016 ADARSH VIDYAMANDIR, CHIVELI, RATNAGIRI 25 25 3 11 9 0 23 92.00 27320104303 25.01.017 NEW ENGLISH SCHOOL, KOSABI-FURUS, RATNAGIRI 39 39 12 19 8 0 39 100.00 27320115803 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 2 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2019 Division : KONKAN Candidates passed School No. -

JEPPESEN MARINE (Formerly C-MAP), UKHO and Norwegian

INDIAN NOTICES TO MARINERS EDITION NO. 04 DATED 16 FEB 2010 (CONTAINS NOTICES 065 TO 074) REACH US 24 x 7 [email protected] +91-135-2748373 [email protected] National Hydrographic Office Joint Director of Hydrography 107-A, Rajpur Road Maritime Safety Services Dehradun – 248001 +91- 135 - 2747360-65 INDIA www.hydrobharat.nic.in CONTENTS Section No. Title I List of Charts Affected II Permanent Notices III Temporary and Preliminary Notices IV Marine Information V Radio Navigational Warnings inforce VI Corrections to Sailing Directions VII Corrections to List of Lights VIII Corrections to List of Radio Signals IX Reporting of Navigational Dangers ST TH (PUBLISHED ON NHO WEBSITE ON 1 & 16 OF EVERY MONTH) FEEDBACK: [email protected] For Indian Ocean Area INSIST ON INDIAN CHARTS AND PUBLICATIONS Original, Authentic and Up-to-Date © Govt. of India Copyright No permission is required to make copies of these Notices. However, such copies are not to be commercially sold. MARINER’S OBLIGATION AND A CHART MAKER’S PLEA. Observing changes at sea proactively and reporting them promptly to the concerned charting agency, is an obligation that all mariners owe to the entire maritime community towards SOLAS. Mariners are requested to notify the Chief Hydrographer to the Government of India at the above mentioned address/fax number/ E mail address immediately on discovering new or suspected dangers to navigation, changes/defects pertaining to navigational aids, and short comings in Indian charts/publications. The Hydrographic Note [Form IH – 102] is a convenient form to notify such changes. Specimen form is attached at Section IX with this notice. -

Konkan LNG Private Limited (KLPL), Dabhol RFQ/ Tender No: KLPL/C&P/ELE/PFL-20/800000020/2019-20 DT 02.08.2019 BIDDING DOCUMENT FOR

Konkan LNG Private Limited (KLPL), Dabhol RFQ/ Tender No: KLPL/C&P/ELE/PFL-20/800000020/2019-20 DT 02.08.2019 BIDDING DOCUMENT FOR FOR DESIGN, SUPPLY, INSTALLATION, TESTING AND COMMISSIONING OF ONE NEW 1010 KVA, 3 PHASE, 6.6 KV,50 HZ DIESEL ENGINE GENERATOR SET AT KLPL LNG PLANT, DABHOL TENDERING UNDER “DOMESTIC COMPETITIVE BIDDING” Prepared and Issued by Konkan LNG Private Limited At & Post Anjanwel, Tal-Guhagar Dist.: Ratnagiri Maharashtra-415634 Ph. No. : 02359-241015 BID/ORINGINAL EMD /POWER OF ATTORNY IS TO BE SUBMITTED AT THE BELOW ADDRESS UNDER TWO BID SYSTEM HOD (C&P), Konkan LNG Private Limited At & Post Anjanwel, Tal-Guhagar Dist.: Ratnagiri Maharashtra-415634 Ph. No. : 02359-241015 Tender No. KLPL/C&P/ELE/PFL-20/800000020/2019-20 for Design, Supply, Installation, Testing and commissioning of one new 1010 KVA, 3 Phase, 6.6 KV,50 Hz DG set at KLPL LNG Plant, Dabhol. Page 1 of 147 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS PLEASE NOTE THAT THIS "REQUEST FOR QUOTATION [RFQ]" IS ON "ZERO-DEVIATION" BASIS. KLPL WILL ACCEPT OFFERS BASED ON TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF THIS "REQUEST FOR QUOTATION [RFQ] & TENDER DOCUMENT" ONLY. DEVIATION TO TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF "REQUEST FOR QUOTATION [RFQ] & TENDER DOCUMENT" MAY LEAD TO REJECTION OF OFFER. "INCOMPLETE BIDS SHALL NOT BE CONSIDERED" PRIOR TO DETAILED EVALUATION, PURSUANT TO "BID EVALUATION AND REJECTION CRITERIA", KLPL WILL DETERMINE THE SUBSTANTIAL RESPONSIVENESS OF EACH BID TO THE "RFQ & TENDER DOCUMENT". FOR THE PURPOSE OF THIS, A SUBSTANTIALLY RESPONSIVE BID IS ONE WHICH CONFORMS TO ALL THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF THE BIDDING DOCUMENTS WITHOUT 'DEVIATIONS' OR 'RESERVATIONS / EXCEPTIONS'. -

Ratnagiri District Maharashtra

1825/DBR/2014 भारत सरकार जल संसाधन मंत्रालय के न्द्रीय भूममजल बो셍 ड GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD महाराष्ट्र रा煍य के अंत셍डत र配नाग셍री जजले की भूजल विज्ञान जानकारी GROUND WATER INFORMATION RATNAGIRI DISTRICT MAHARASHTRA By 饍िारा S.S.P. MISHRA एस. एस. पी. ममश्रा Superintending Hydrogeologist अगधक्षण भजू ल बैज्ञाननक मध्य क्षेत्र, ना셍परु CENTRAL REGION NAGPUR 2014 RATNAGIRI DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical Area : 8326 sq. km. Administrative Divisions : Taluka-9; Ratnagiri, Sangameshwar, (As on 31/03/2007) Chiplun, Guhagar, Khed, Dapoli, Mandangad, Lanja and Rajapur. Villages : 1543 Population : 16,97,000 Normal Annual Rainfall : 2658 mm to 3973 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic unit : 5; Coastline, Estuarine plains, Lateritic plateaus, Residual hills, Scrap faces of Sahayadri. Major Drainage : 6; Savitri, Vasisthi, Shastri, Ratnagiri, Jaitapur, Wagothan. 3. LAND USE (2010-11) Forest Area : 60.0 sq. km. Net Area Sown : 2630 sq. km. Cultivable Area : 4010 sq. km. 4. SOIL TYPE Coarse shallow soil, medium deep soil, deep soil along river banks, coastal alluvium and coastal saline. 5. PRINCIPAL CROPS (2000-01) Paddy : 772 sq. km. Cereals : 1020 sq. km. Oil Seeds : 30 sq. km. Nachani : 173 sq. km. Cashewnut/Coconut/Supari : 928 Sq km 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (2010-11) - Dugwells/Tube wells : 2263 ha Canal Irrigation 6273 Ha Tanks/Ponds : 244/586 Net Irrigated Area : 14603 ha 7. GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS (As on 31/03/2007) Dugwells : 48 Piezometers : 4 8. -

District-Driven Growth a Pilot Study for Making India

FINAL DISTRICT-DRIVEN GROWTH A PILOT STUDY FOR MAKING INDIA A $5 TRILLION ECONOMY REPORT FOR RATNAGIRI DISTRICT SUBMITTED BY: NATIONAL COUNCIL OF APPLIED ECONOMIC RESEARCH JANUARY, 2019 NCAER DIPP District Driven Growth Pilot Study Ratnagiri ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The NCAER study team would like to thank the officials of DIPP and MoCI for their support and guidance through the course of the study. At DIPP, we are thankful to Mr. Anand S. Bhal, Senior Economic Adviser for his suggestions and cooperation. Our special thanks to his team members, particularly Mr. Sandip Kote, Ms. Kokila Jayaram and Ms. Supriya Malik for their support and for connecting us with the district officials. At MoCI, the team had a privilege to interact with the Hon. Minister, Mr. Suresh Prabhu and get his valuable insights on the scope of the study. His officials, particularly Mr. Digvijay Sujlana and Mr. Abheet Dwivedi, have been a wonderful support in all aspects of the study, especially in arranging meetings with the officials from the district and state capital departments. The team benefitted immensely from the insightful meetings with the district stakeholders. The team would like to express its gratitude to the District Collector and District Magistrate, Mr. Sunil Chavan, IAS, for having discussions with us on the district potential areas. We had rounds of extensive discussions – with Chief Executive Officer, Additional Chief Executive Officer, District Statistical Office, Maharashtra State Agricultural Marketing Board, Ratnagiri Zonal office: Bank of India (Lead Bank of the district), Associate Dean of College of Fisheries, Assistant Commissioner of Fisheries Department, District Industries Center, District Superintendent Agriculture Officer and District Planning Officer. -

Konkan LNG Limited (KLL)

TENDER NO.: KLL/HQ/C&P/16/2020 ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL AUDITORS FOR F. Y. 2020-21. Konkan LNG Limited (KLL) RFQ/Tender No: KLL/HQ/C&P/16/2020 BIDDING DOCUMENT FOR: TENDER FOR ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL AUDITORS FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2020-21. Prepared and Issued by Konkan LNG Limited Gail Jubilee Tower 13th Floor, B-35 & 36, Sector-1, Noida -201301 1 TENDER NO.: KLL/HQ/C&P/16/2020 ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL AUDITORS FOR F. Y. 2020-21. SECTION-I Ref No: KLL/HQ/C&P/16/2020 Date: 19.08.2020 To PROSPECTIVE BIDDERS SUB: TENDER FOR ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL AUDITORS FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2020-21. Dear Sir/Madam, 1.0 KLL invites bids from bidders for the subject work of “TENDER FOR ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL AUDITORS FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2020-21.” 2.0 The brief details of the tender are as under: TENDER FOR ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL Nature of Service (A) required AUDITORS FOR FINANCIAL YEAR 2020-21. TENDER NO. & KLL/HQ/C&P/16/2020 date: 19.08.2020 (B) DATE SINGLE BID SYSTEM TYPE OF BIDDING (C) SYSTEM TWO BID SYSTEM E-TENDER (D) TYPE OF TENDER MANUAL The bidders can raise the query, within 7 days from the (E) Pre-Bid Meeting date of issue of the tender. Physical pre bid meeting will not be held due to COVID-19 situation. As per the Scope of Work Attached in Section –VI of the (F) Completion Period tender document. APPLICABLE BID SECURITY / EARNEST MONEY NOT (G) DEPOSIT (EMD) APPLICABLE 2 TENDER NO.: KLL/HQ/C&P/16/2020 ENGAGEMENT OF INTERNAL AUDITORS FOR F. -

Mir Mohammad Momin Astarabadi's Contribution To

Shaikh Musak Rajjak 1 Mir Mohammad Momin Astarabadi’s Contribution to Qutb Shahi Deccan History Abstract Mir Mohammad Momin Astarabadi (1553-1626), was an immigrant who left a career at the Safavid court and came to the Qutb Shahi to serve as the top advisor at the Qutb Shahi’s court from c. 1581 to 1625. He worked as Peshwa (prime minister) under Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah and Muhammad Qutb Shah. He was second in power only to the Sultan, in addition to being a noted poet and a respected and devout member of the Ulama. He contributed the Qutb Shahi Deccan period with his scholarship and the literature. The Persian manuscript Insha-i Qasir-i Tabbasi, in the Salar Jung Museum (A.N. 31) gives the information about the history of Qutb Shahi Deccan and the relations with Safavid Empire of Iran. The relations between Qutb Shahi, Mughals and Safavid Empires were very deep and historical. The Central Asia, Iran, Northern Hindustan and Deccan had a vast world of shared linguistic (Persian) and cultural practices. As Muzaffar Alam noted that, the Iranian could arrive in a strange, immediately find their bearings, and function with a great deal of ease; at Mughal or Qutb Shahi courts. Indians and Iranians had very relevant interconnections from Ancient to Medieval times in history. T. N. Devare, Muhiuddin Qadri Zore, H.K. Sherwani, Muzaffar Alam, Sanjay Subrahmanyam and Laura Weinstein focused on the history and personality of Mir Mohammad Momin Astarabadi in their works and research articles. The proposed research paper focuses on the contribution of Mir Mohammad Momin Astarabadi in the field of Deccan heritage and the history of Qutb Shahi Deccan.