Crisis and Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 34159 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS AVIATION SAFETY and NOISE Millions of People Around Major Airports

November 29, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 34159 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS AVIATION SAFETY AND NOISE millions of people around major airports. It On October 22 the Senate passed H.R 2440, would also weaken the incentives for replace striking the provisions of the House ini REDUCTION ACT ment of aircraft with new technology air tiated b111 and substituting for them the planes that could offer even more noise relief provisions of S. 413, the Senate "noise bill". to the millions of Americans who are ex I am advised the Senate has already ap HON. NORMAN Y. M!NETA posed daily to unacceptable levels of aircraft pointed conferees in anticipation of a con OF CALIFORNLA noise. ference on H.R. 2440. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 3. By authorizing some $300 mi111on in In expressing the Administration's opposi excess of the President's budget for FY 1980, tion to H.R. 3942, I outlined a number of Thursday, November 29, 1979 an increase which ls unwarranted, the bill objectionable features of the b1ll. The pro e Mr. MINETA. Mr. Speaker, I ha;ve would be infiationary. In any event, as you visions of H.R. 2440, as passed by the Senate, asked the White House for a clear sig know, the House already acted to establish a.ire comparable in many respects to those an obligations limit on the airport devel undesirable fiseal and environmental provi nal that legislation rolling back the fieet opment program for 1980 at a level which is sions of H.R. 3942 to which we are opposed; noise rule would be vetoed. -

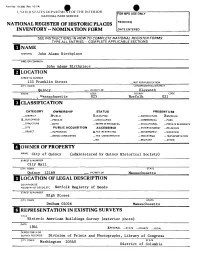

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form | Name (Owner of Property Location of Legal Description 1 Repr

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) ^M U NITbD STATES DEPARTMEm OF THE INTERIOR FOR «PS USE OHtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED. INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC John Adams Birthplace AND/OR COMMON John Adams Birthplace Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 133 Franklin Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Quincy —. VICINITY OF Eleventh STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Norfolk 021 Q CLASSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM X_BUILOING(S) _PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL _ PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL _ PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED _ INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME city of Quincy (administered by Quincy Historical Society) STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Quincy 12169 VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Norfolk Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER High Street CITY, TOWN STATE Dedham 02026 Massachusetts 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (exterior photo) DATE 1941 XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress __- CITY. TOWN Washington 20540 District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE — EXCELLENT _ DETERIORATED __UNALTERED JWRIGINALSITE XGOOD XALTERED __FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Adams Birthplace stands on the west side of Franklin Street (number 133) approximately 150 feet from its intersection with Presidents Avenue. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Redefining Interpretation at America's Eighteenth-Century Heritage Sites Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67b4c877 Author Lindsay, Anne Marie Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Redefining America‘s Eighteenth-Century Heritage Sites A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Marie Lindsay August 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Catherine Allgor, Chairperson Dr. Sharon Salinger Dr. Christine Gailey Copyright by Anne Marie Lindsay 2010 The Dissertation of Anne Marie Lindsay is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements As this dissertation argues, history does not exist in a vacuum and no man stands alone. I have accomplished this work through the support of many friends, family members, and colleagues. I thank my dissertation committee for their support and advice over several years. Christine Gailey, Sharon Salinger, and Catherine Allgor have provided me with valuable insight that I could not have done without. I particularly thank Catherine Allgor, my chair, for allowing me the freedom to explore when necessary and also the structure to rein me in. Without her encouragement, unwavering belief in my work, and colorful note cards, I could not have reached this goal. Thank you to Cliff Trafzer, for bringing me to UCR as a public history MA student, and encouraging me no matter what I was doing. I have had the privilege to work with a number of public historians who have guided me in my scholarly and professional endeavors. -

Adams National Historical Park Foundation Document Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Adams National Historical Park Massachusetts Contact Information For more information about the Adams National Historical Park Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 617-773-1177 or write to: Superintendent, Adams National Historical Park, 135 Adams Street, Quincy, MA 02169 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Adams National Historical Park resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • Adams National Historical Park encompasses the birthplaces, burial place, and the Old House at Peace field and Stone Library of the first father-son Presidents John and John Quincy Adams, and provides opportunities to connect with the places that shaped the lives and ideas of the statesmen who, through lengthy domestic and international public service, had a profound and lasting influence on United States nation building, constitutional theory, and international diplomacy. • With Peace field as a touchstone, Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, first ladies Abigail Adams and Louisa Catherine Adams, Ambassador Charles Francis Adams, historians Henry Adams, Brooks Adams, Charles The purpose of ADAMS NATIOnaL Francis Adams, Jr., and Clover Adams made distinguished HISTORICAL PARK is to preserve, protect, contributions in public and private service and in American maintain, and interpret the homes, literature, arts, and intellectual life. -

Public Law 95-625 95Th Congress an Act to Authorize Additional Appropriations for the Acquisition of Lands and Interests Nov

PUBLIC LAW 95-625—NOV. 10, 1978 92 STAT. 3467 Public Law 95-625 95th Congress An Act To authorize additional appropriations for the acquisition of lands and interests Nov. 10. 1978 in lands within the Sawtooth National Recreation Area in Idaho. [S. 791] Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the^ United States of America in Congress asserribled^ National Parks and Recreation SHORT TITLE AND TABLE OF CONTENTS Act of 1978. SECTION 1. This Act may be cited as the "National Parks and 16 USC 1 note. Recreation Act of 1978". TABLE OF CONTENTS Sec. 1. Short title and table of contents. Sec. 2. Definition. Sec. 3. Authorization of appropriations. TITLE I—DEVELOPMENT CEILING INCREASES Sec. 101. Specific increases. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. Andersonville National Historic Site. Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. Biscayne National Monument. Capitol Reef National Park. Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. Cowpens National Battlefield Site. De Soto National Memorial. Fort Bowie National Historic Site. Frederick Douglass Home, District of Clolumbia. Grant Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site. Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Gulf Islands National Seashore. Harper's Ferry National Historical Park. Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. John Muir National Historic Site. Lands in Prince Georges and Charles Counties, Maryland. Longfellow National Historic Site. Ptecos National Monument. Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial. San Juan Island National Historical Park. Sitka National Historical Park. Statue of Liberty National Monument. Thaddeus Kosciuszko Home National Historic Site. Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site. Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area. William Howard Taf t National Historic Site. -

The Historic Interpretation of Slavery at the Homes of Five Founding Fathers

Pride and Prejudice: The Historic Interpretation of Slavery at the Homes of Five Founding Fathers by Amanda G. Seymour B.A. in Anthropology & Italian Studies, The University of Virginia A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 19, 2013 Thesis directed by Jeffrey P. Blomster Associate Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs To Evy ii Acknowledgements I am grateful to my thesis director, Dr. Jeffrey Blomster and my second reader, Max van Balgooy for their patience and guidance throughout this process. I would also like to thank my co-workers in the Office of the Provost at The George Washington University, who have shown an extraordinary level of compassion and understanding for my situation as both a graduate student and university employee. The friendships that I have made in the Anthropology Department are the kind that will last forever, and the support system we have created has been essential to the completion of my master's degree. And thanks goes to my in-town uncle and aunt, Gene and Marie, whose dinner invitations and dog-sitting needs provided some much needed solace. Special thanks go to my immediate family: Mom, Dad, and Tori, who have been a source of comfort (and escape) when I have been in need. iii Table of Contents Dedication............................................................................................................................ ii Acknowledgements............................................................................................................ -

John Quincy Adams Birthplace

Form NO. io^3oo (Rev. io-74) NATIONAL ^STORIC LANDMARK THEME: P^TTICAL $ MILITARY AFFAIRS UNIThD STATES DLPARTMUvf OF THli INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEEINSTRUCTIONSINWOW7O COMPLETE NA TIONA L REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC John Quincy Adams Birthplace AND/OR COMMON John Quincy Adams Birthplace I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 141 Franklin Street _JSIOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Quincy _ VICINITY OF Eleventh STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mfl « fl ^iic.-H-c ° 25 N °rfolk ° 21 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X_PUBLIC XOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM X^BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK tN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS 1LYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _8EING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. QOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Quincy (administered by Quincy Historical Society) STREETS* NUMBER City Hall CITY. TOWN STATE Quincy 02169 _ VICINITY OF Massachusetts HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Norfolk Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER High Street CITY, TOWN STATE Dedham . 02026 Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey [exterior photo) DATE 1941 ^.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Prints and Photographs , Library of Congress CITY, TOWN STATE Washington 20540 District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .^EXCELLENT ^.DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^—ORIGINAL SITE _RUtNS X—ALTERED __MOVED DATE _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Quincy Adams Birthplace is located near the west curbline of Franklin Street (number 141) just north of its intersection with Presidents Avenue. -

Junior Ranger Program Activity Book for Ages 9 and Up

Junior Ranger Program Activity book for ages 9 and up Adams National Historical Park QUINCY, MASSACHUSETTS Welcome Welcome to Adams National Historical Park. It’s nice to meet you! Our names are Maggie and Jack. We will be your guides as you work toward becoming a Junior Ranger! Junior Rangers are very important to the National Park Service. Here at Adams National Historical Park, Junior Rangers help take care of some of our nation’s special places by learning the history this booklet belongs to of the Adams family and their role in the American Revolution and the birth of our nation. Becoming a Junior Ranger is easy! With the help of an adult and the Park Rangers, complete any 5 of the activities in this booklet during your visit and you’ll receive your very own Junior Ranger Badge. Wear it proudly! SE A U P E E S N A C E I L L P ! Thank you for your interest in the Junior Ranger program! This activity booklet is intended for children ages 9 and above. Some of the activities planned for today include: viewing the film “Enduring Legacy” prior to boarding the trolley, exploration of exhibits in the Visitor Center, conversations with a Park Ranger, guided tours of the Adams’ birthplaces and the “Old House at Peace field,” and exploration of the grounds and gardens. If you have any questions about today’s activities, please do not hesitate to ask one of the Park Rangers. Enjoy your visit! 1 Tour Map QUESTIONS The first member of the Adams family to arrive on DIRECTIONS 1. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form | Name

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) ^M U NITbD STATES DEPARTMEm OF THE INTERIOR FOR «PS USE OHtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED. INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC John Adams Birthplace AND/OR COMMON John Adams Birthplace Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 133 Franklin Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Quincy —. VICINITY OF Eleventh STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Norfolk 021 Q CLASSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM X_BUILOING(S) _PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL _ PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL _ PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED _ INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME city of Quincy (administered by Quincy Historical Society) STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Quincy 12169 VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Norfolk Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER High Street CITY, TOWN STATE Dedham 02026 Massachusetts 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (exterior photo) DATE 1941 XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress __- CITY. TOWN Washington 20540 District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE — EXCELLENT _ DETERIORATED __UNALTERED JWRIGINALSITE XGOOD XALTERED __FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Adams Birthplace stands on the west side of Franklin Street (number 133) approximately 150 feet from its intersection with Presidents Avenue. -

HR 12536, House Report 95-1165, May 15, 1978

95TH CONGRESS MOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES I REPORT 2d Session f No. 95-1165 PROVIDING FOR INCREASES IN APPROPRIATIONS CEILINGS, DE- VELOPMENT CEILINGS, LAND ACQUISITION AND BOUNDARY CHANGES IN CERTAIN FEDERAL PARK AND RECREATION AREAS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES MAY 15, 1978.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. UDALL, from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, submitted the following REPORT together with SUPPLEMENTAL VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 12536] [Including the cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, to whom was re- ferred the bill (H.R. 12536) to provide increases in appropriations ceilings, development ceilings, land acquisition, and boundary changes in certain Federal park and recreation areas, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon with an amend- ment and recommend that the bill as amended do pass. The amendment is as follows: Page 1, beginning on line 3, strike out all after the enacting clause and insert in lieu thereof the following: SHORT TITLE AND TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1. This Act may be cited as the "National Parks -and Recreation Act of 1978" TABLE OF CONTENTS Sec. 1. Short title and table of contents Sec. 2. Definition. Sec. 3. Authorization of appropriations. * 27-867 0 TITLE I-DEVELOPMENT OF CEILING INCREASES Sec. 101. Specific increases. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. Andersonville National Historic Site. Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. Biscayne National Monument. Canaveral National Seashore. Cape Lookout National Seashore. Capital Reef National Park. -

Public Law 95-625 95Th Congress an Act

PUBLIC LAW 95-625-NOV. 10, 1978 92 STAT. 3467 Public Law 95-625 95th Congress An Act To authorize additional appropriations for the acquisition of lands and interests Nov. lO, l978 in lands within the Sawtooth National Recreation Area in Idaho. [S. 791) Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the, United States of America in Congress assembled, National Parks and Recreation SHORT TITLE AND TABLE OF CONTENTS Act of 1978. SECTION 1. This Act may be cited as the "National Parks and 16 USC 1 note. Recreation Act of 1978". TABLE OF CONTENTS Sec. 1. Short title and table of contents. Sec. 2. Definition. Sec. 3. Authorization of appropriations. TITLE I-DEVELOPMENT CEILING INCREASES Sec. 101. Specificincreases. Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. Andersonville National Historic Site. Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. Biscayne National Monument. Capitol Reef National Park. Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. Cowpens National Battlefield Site. De Soto National Memorial. Fort Bowie National Historic Site. Frederick Douglass Home, District of Oolumbia. Grant Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site. Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Gulf Islauds National Seashore. Harper's Ferry National Historical Park. Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. John Muir National Historic Site. Lands in Prince Georges and Charles Counties, Maryland. Longfellow National Historic Site. Pecos National Monument. Perry'sVictory and lnternational Peace Memorial. San Juan Island National Historical Park. Sitka National Historical Park. Statue of Liberty National Monument. ThaddeusKosciuszko Home National Historic Site. Tuskegee Institute National HistoricSite. Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area. William Howard Taft National Historic Site.