2011 Colleen Bevin Kennedy-Karpat ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti

From Page to Screen: the Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti Lucia Di Rosa A thesis submitted in confomity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) Graduate Department of ltalian Studies University of Toronto @ Copyright by Lucia Di Rosa 2001 National Library Biblioth ue nationale du Cana2 a AcquisitTons and Acquisitions ef Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeOingtOn Street 305, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Otiawa ON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive ~~mnettantà la Natiofliil Library of Canarla to Bibliothèque nation& du Canada de reprcduce, loan, disûi'bute or seil reproduire, prêter, dishibuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format é1ectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, From Page to Screen: the Role of Literatuce in the Films af Luchino Vionti By Lucia Di Rosa Ph.D., 2001 Department of Mian Studies University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation focuses on the role that literature plays in the cinema of Luchino Visconti. The Milanese director baseci nine of his fourteen feature films on literary works. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

43E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle Du 26 Juin Au 5 Juillet 2015 Le Puzzle Des Cinémas Du Monde

43e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle du 26 juin au 5 juillet 2015 LE PUZZLE DES CINÉMAS DU MONDE Une fois de plus nous revient l’impossible tâche de synthétiser une édition multiforme, tant par le nombre de films présentés que par les contextes dans lesquels ils ont été conçus. Nous ne pouvons nous résoudre à en sélectionner beaucoup moins, ce n’est pas faute d’essayer, et de toutes manières, un contexte économique plutôt inquiétant nous y contraint ; mais qu’une ou plusieurs pièces essentielles viennent à manquer au puzzle mental dont nous tentons, à l’année, de joindre les pièces irrégulières, et le Festival nous paraîtrait bancal. Finalement, ce qui rassemble tous ces films, qu’ils soient encore matériels ou virtuels (50/50), c’est nous, sélectionneuses au long cours. Nous souhaitons proposer aux spectateurs un panorama généreux de la chose filmique, cohérent, harmonieux, digne, sincère, quoique, la sincérité… Ambitieux aussi car nous aimons plus que tout les cinéastes qui prennent des risques et notre devise secrète pourrait bien être : mieux vaut un bon film raté qu’un mauvais film réussi. Et enfin, il nous plaît que les films se parlent, se rencontrent, s’éclairent les uns les autres et entrent en résonance dans l’esprit du festivalier. En 2015, nous avons procédé à un rééquilibrage géographique vers l’Asie, absente depuis plusieurs éditions de la programmation. Tout d’abord, avec le grand Hou Hsiao-hsien qui en est un digne représentant puisqu’il a tourné non seulement à Taïwan, son île natale mais aussi au Japon, à Hongkong et en Chine. -

Max-Ophuls.Pdf

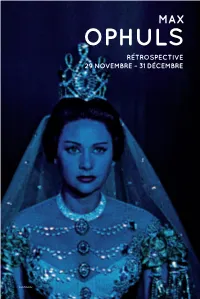

MAX OPHULS RÉTROSPECTIVE 29 NOVEMBRE – 31 DÉCEMBRE Lola Montès Divine GRAND STYLE Né en Allemagne, auteur de plusieurs mélodrames stylés en Allemagne, en Italie et en France dans les années 1930 (Liebelei, La signora di tutti, De Mayerling à Sarajevo), Max Ophuls tourne ensuite aux États-Unis des films qui tranchent par leur secrète inspiration « mitteleuropa » avec la tradition hollywoodienne (Lettre d’une inconnue). Il rentre en France et signe coup sur coup La Ronde, Le Plaisir, Madame de… et Lola Montès. Max Ophuls concevait le cinéma comme un art du spectacle. Un art de l’espace et du mouvement, susceptible de s’allier à la littérature et de s’inspirer des arts plastiques, mais un art qu’il pratiquait aussi comme un art du temps, apparen- té en cela à la musique, car il était de ceux – les artistes selon Nietzsche – qui sentent « comme un contenu, comme « la chose elle-même », ce que les non- artistes appellent la forme. » Né Max Oppenheimer en 1902, il est d’abord acteur, puis passe à la mise en scène de théâtre, avant de réaliser ses premiers films entre 1930 et 1932, l’année où, après l’incendie du Reichstag, il quitte l’Allemagne pour la France. Naturalisé fran- çais, il doit de nouveau s’exiler après la défaite de 1940, travaille quelques années aux États-Unis puis regagne la France. LES QUATRE PÉRIODES DE L’ŒUVRE CINEMATHEQUE.FR Dès 1932, Liebelei donne le ton. Une pièce d’Arthur Schnitzler, l’euphémisme de Max Ophuls, mode d’emploi : son titre, « amourette », qui désigne la passion d’une midinette s’achevant en retrouvez une sélection tragédie, et la Vienne de 1900 où la frivolité contraste avec la rigidité des codes subjective de 5 films dans la sociaux. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

"To Rely on Verdi's Harmonies and Not on Wagnerian Force." the Reception of Ltalian Cinema in Switzerland, 1 939-45

GIANNI HAVER "To Rely on Verdi's Harmonies and not on Wagnerian Force." The Reception of ltalian Cinema in Switzerland, 1 939-45 Adopting an approach that appeals to the study of reception means em- phasising an analysis of the discourses called forth by films rather than an analysis of the films themselves. To be analysed, these discourses must have left certain traces, although it is of course difficult to know what two spectators actually said to one another on leaving a cinema in L939. The most obvious, visible, and regular source of information are film reviews in the daily press. Reception studies have, moreover, often privileged such sources, even if some scholars have drawn attention to the lack of com- pliance between the expression of a cultured minority - the critics - and the consumption of mass entertainment (see Daniel 1972, 19; Lindeperg 1997, L4). L. *y view, the press inevitably ranks among those discourses that have to be taken into consideratiorL but it is indispensable to confront it with others. Two of these discourses merit particular attentiory namely that of the authorities, as communicated through the medium of censor- ship, and that of programming, which responds to rules that are chiefly commercial. To be sure, both are the mouthpieces of cultural, political, and economic elites. Accordingly, their discourses are govemed by the ruling classes, especially with regard to the topic and period under investiga- tion here: the reception of Italian cinema in Switzerland between 1939 and 1945. The possibilities of expressing opposition were practically ruled out, or at least muted and kept under control. -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

On This Date Daily Trivia Happy Birthday! Quote Of

THE SUNDAY, AUGUST 1, 2021 On This Date 1834 – The Emancipation Act was Quote of the Day enacted throughout the British “Study as if you were going to Dominions. Most enslaved people were live forever; live as if you re-designated as “apprentices,” and were going to die tomorrow.” their enslavement was ended in stages over the following six years. ~ Maria Mitchell 1941 – The first Jeep, the army’s little truck that could do anything, was produced. The American Bantam Happy Birthday! Car Company developed the working Maria Mitchell (1818–1889) was the prototype in just 49 days. General first professional female astronomer Dwight D. Eisenhower said that the in the United States. Born in Allies could not have won World Nantucket, Massachusetts, Mitchell War II without it. Because Bantam pursued her interest in astronomy couldn’t meet the army’s production with encouragement from her demands, other companies, including parents and the use of her father’s Ford, also started producing Jeeps. telescope. In October 1847, Mitchell discovered a comet, a feat that brought her international acclaim. The comet became known as “Miss Mitchell’s Comet.” The next year, the pioneering stargazer became the first woman admitted to the Daily Trivia American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Jeep was probably named after Mitchell went on to Eugene the Jeep, a Popeye comic become a professor strip character known for its of astronomy at magical abilities. Vassar College. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) UNDAY UGUST S , A 1, 2021 Today is Mahjong Day. While some folks think that this Chinese matching game was invented by Confucius, most historians believe that it was not created until the late 19th century, when a popular card game was converted to tiles. -

A Mode of Production and Distribution

Chapter Three A Mode of Production and Distribution An Economic Concept: “The Small Budget Film,” Was it Myth or Reality? t has often been assumed that the New Wave provoked a sudden Ibreak in the production practices of French cinema, by favoring small budget films. In an industry characterized by an inflationary spiral of ever-increasing production costs, this phenomenon is sufficiently original to warrant investigation. Did most of the films considered to be part of this movement correspond to this notion of a small budget? We would first have to ask: what, in 1959, was a “small budget” movie? The average cost of a film increased from roughly $218,000 in 1955 to $300,000 in 1959. That year, at the moment of the emergence of the New Wave, 133 French films were produced; of these, 33 cost more than $400,000 and 74 cost more than $200,000. That leaves 26 films with a budget of less than $200,000, or “low budget productions;” however, that can hardly be used as an adequate criterion for movies to qualify as “New Wave.”1 Even so, this budgetary trait has often been employed to establish a genealogy for the movement. It involves, primarily, “marginal” films produced outside the dominant commercial system. Two Small Budget Films, “Outside the System” From the point of view of their mode of production, two titles are often imposed as reference points: Jean-Pierre Melville’s self-produced Silence of 49 A Mode of Production and Distribution the Sea, 1947, and Agnes Varda’s La Pointe courte (Short Point), made seven years later, in 1954. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

ART HISTORY REVEALED Dr

ART HISTORY REVEALED Dr. Laurence Shafe This course is an eclectic wander through art history. It consists of twenty two-hour talks starting in September 2018 and the topics are largely taken from exhibitions held in London during 2018. The aim is not to provide a guide to the exhibition but to use it as a starting point to discuss the topics raised and to show the major art works. An exhibition often contains 100 to 200 art works but in each two-hour talk I will focus on the 20 to 30 major works and I will often add works not shown in the exhibition to illustrate a point. References and Copyright • The talks are given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • The notes are based on information found on the public websites of Wikipedia, Tate, National Gallery, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story. • If a talk uses information from specific books, websites or articles these are referenced at the beginning of each talk and in the ‘References’ section of the relevant page. The talks that are based on an exhibition use the booklets and book associated with the exhibition. • Where possible images and information are taken from Wikipedia under 1 an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 ART HISTORY REVEALED 1. Impressionism in London 1. -

Modigliani Large Print Guide Room 1–11

MODIGLIANI 23 November 2017 – 2 April 2018 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to exhibition entrance RO OM 1–11 CONTENTS Room 1 4 Room 2 7 Room 3 18 Room 4 28 Room 5 36 Room 6 43 Room 7 53 Room 8 68 Room 9 77 Room 10 85 Room 11 91 Find Out More 100 5 6 4 7 3 8 2 9 1 10 10 11 Let us know what you think #Modigliani 3 ROOM 1 4 Open To Change When Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) decided to leave Italy to develop his career as an artist, there was only one place to go. In 1906, at the age of 21, he moved to Paris. Many factors shaped his decision. Born in the port city of Livorno, he belonged to an educated family of Sephardic Jews (descended from Spain and Portugal), who encouraged his ambition and exposed him to languages and literature. He had seen great Renaissance art and had trained as a painter. But Paris offered excitement. Paris offered variety. There he would encounter ways of thinking, seeing and behaving that challenged and shaped his work. This exhibition opens with a self-portrait, painted around 1915, in which Modigliani presents himself as the tragic clown Pierrot. His contemporaries would have recognised the reference instantly as, at the time, the figure appeared in countless pictures, plays and films. A young person shaping their identity could relate to Pierrot, a stock character open to interpretation, linked to the past and looking towards the future. Pierrot could be comedic, melancholy or romantic, played by any actor or painted by any artist.