Chapter Five Social-Property Relations, Class-Conflict And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncertainty and Civil War Onset

Uncertainty and Civil War Onset Iris Malone∗ Abstract Why do some armed groups escalate their campaigns to civil war, while others do not? Only 25% of the 960 armed groups formed between 1970 and 2012 became violent enough to surpass the 25-battle death threshold, often used to demarcate \civil conflict.” I develop a new theory that argues this variation occurs because of an information problem. States decide how much counterinsurgency effort to allocate for repression on the basis of observable characteristics about an armed group's initial capabilities, but two scenarios make it harder to get this decision right, increasing the risk of civil war. I use fieldwork interviews with intelligence and defense officials to identify important group characteristics for civil war and apply machine learning methods to test the predictive ability of these indicators. The results show that less visible armed groups in strong states and strong armed groups in weak states are most likely to lead to civil war onset. These findings advance scholarly understanding about why civil wars begin and the effect of uncertainty on conflict. ∗Department of Political Science, 100 Encina Hall West, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. ([email protected], web.stanford.edu/~imalone). 1 Introduction Why do some armed groups escalate their campaigns to civil war, while most do not? Using an original dataset, I show that only 25% of the 960 armed groups formed between 1970 and 2012 became violent enough to surpass the 25-battle death threshold, often used to demarcate \civil conflict.”1 Only 8% of armed groups surpassed the higher \civil war" threshold of 1000 fatalities per year. -

Social-Property Relations, Class-Conflict and The

Historical Materialism 19.4 (2011) 129–168 brill.nl/hima Social-Property Relations, Class-Conflict and the Origins of the US Civil War: Towards a New Social Interpretation* Charles Post City University of New York [email protected] Abstract The origins of the US Civil War have long been a central topic of debate among historians, both Marxist and non-Marxist. John Ashworth’s Slavery, Capitalism, and Politics in the Antebellum Republic is a major Marxian contribution to a social interpretation of the US Civil War. However, Ashworth’s claim that the War was the result of sharpening political and ideological – but not social and economic – contradictions and conflicts between slavery and capitalism rests on problematic claims about the rôle of slave-resistance in the dynamics of plantation-slavery, the attitude of Northern manufacturers, artisans, professionals and farmers toward wage-labour, and economic restructuring in the 1840s and 1850s. An alternative social explanation of the US Civil War, rooted in an analysis of the specific path to capitalist social-property relations in the US, locates the War in the growing contradiction between the social requirements of the expanded reproduction of slavery and capitalism in the two decades before the War. Keywords origins of capitalism, US Civil War, bourgeois revolutions, plantation-slavery, agrarian petty- commodity production, independent-household production, merchant-capital, industrial capital The Civil War in the United States has been a major topic of historical debate for almost over 150 years. Three factors have fuelled scholarly fascination with the causes and consequences of the War. First, the Civil War ‘cuts a bloody gash across the whole record’ of ‘the American . -

Race, Class, and Slavery During the American Civil

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Marx’s Intertwining of Race and Class During the Civil War in the U.S. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6238s7h2 Journal Journal of Classical Sociology, 17(1) Author Anderson, Kevin Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Marx’s Intertwining of Race and Class During the Civil War in the U.S. Kevin B. Anderson, University of California, Santa Barbara [author’s last version of article published in Journal of Classical Sociology 17:1 (2017), pp. 24-36] As the U.S. marked the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, some attention was given to African-American resistance to slavery and to the northern radical abolitionists. Increasingly, it was admitted, even in the South, that the Confederacy’s supposedly “noble cause” was based upon the defense of slavery. Yet to this day U.S. public opinion continues to deny the race and class dimensions of the war. There is also a denial, sometimes even among critical sociologists, of the war’s revolutionary implications, not only for African-Americans, but also for white labor and for the U.S. economic and political system as a whole. And there is still greater ignorance of the fact that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote extensively on the dialectics of race and class in the American Civil War, something I have tried to remedy in my recent book, Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies. Marx on Ireland: Class, Ethnicity, and National Liberation Sometimes, as I have tried to show in Marx at the Margins, Marx conceptualized the pathway to class-consciousness and to socialist revolution as direct rather than indirect. -

Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain During the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2012 Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 Annalise Policicchio Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Policicchio, A. (2012). Propaganda Use by the Union and Confederacy in Great Britain during the American Civil War, 1861-1862 (Master's thesis, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1053 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 A Thesis Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Degree of Masters of History By Annalise L. Policicchio August 2012 Copyright by Annalise L. Policicchio 2012 PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. Policicchio Approved May 2012 ____________________________ ______________________________ Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Perry Blatz, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History Associate Professor of History Thesis Director Thesis Reader ____________________________ ______________________________ James C. Swindal, Ph.D. Holly Mayer, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College & Graduate Chair, Department of History School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT PROPAGANDA USE BY THE UNION AND CONFEDERACY IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1862 By Annalise L. -

The Extremist's Advantage in Civil Wars

The Extremist’s Advantage in Civil Wars The Extremist’s Barbara F. Walter Advantage in Civil Wars One of the puzzles of the current wave of civil wars is that rebel groups espousing extremist ideologies—especially Salaª jihadism—have thrived in ways that moderate rebels have not.1 Groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State (also known by the acronym ISIS) have attracted more recruits, foreign soldiers, and ªnancing than corresponding moderate groups such as the Free Syrian Army, Ahlu Sunna Waljamaa, or Jaysh Rijaal al-Tariqa al-Naqshbandia (JRTN).2 The proliferation and success of extremist groups is particularly surprising given that their goals are far more radical than those of the populations they seek to represent.3 Salaª jihadists aim to establish a transnational caliphate using military force, an objective the vast majority of Muslims do not support.4 Why have so many extremist groups emerged in countries experiencing civil wars since 2003, and why have they thrived in ways that moderate groups have not? Barbara F. Walter is Professor of Political Science at the School of Global Policy and Strategy at the Univer- sity of California, San Diego. The author thanks Jesse Driscoll, Isaac Gendel, Dotan Haim, Ron Hassner, Allison Hodgkins, Joshua Kertzer, Aila Matanock, William McCants, Assaf Moghadam, Richard Nielsen, Emily Ritter, Michael Stohl, and Keren Yarhi-Milo for their willingness to read the manuscript and offer helpful feedback. She is especially grateful to Gregoire Phillips for answering an endless series of questions with enormous good cheer. Finally, she thanks the participants of the International Rela- tions Faculty Colloquium at Princeton University for inviting her to present this work and follow- ing up with thoughtful suggestions. -

The Civil War

Soldiers HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY The Civil War Reader Ulysses S. Grant Robert E. Lee Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad Abraham Lincoln THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. The Civil War Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

War and Media: Constancy and Convulsion

Volume 87 Number 860 December 2005 War and media: Constancy and convulsion Arnaud Mercier* Arnaud Mercier is professor at the university Paul Verlaine, Metz (France) and director of the Laboratory “Communication and Politics” at the French National Center for Scientifi c Research (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifi que, CNRS). Abstract To consider the relationship between war and the media is to look at the way in which the media are involved in conflict, either as targets (war on the media) or as an auxiliary (war thanks to the media). On the basis of this distinction, four major developments may be cited that today combine to make war above all a media spectacle: photography, which opened the door to manipulation through stage-management; live technologies, which raise the question of journalists’ critical distance vis-à-vis the material they broadcast and which can facilitate the process of using them; pressure on the media and media globalization, which have led to a change in the way the political and military authorities go about making propaganda; and, finally, the fact that censorship has increasingly come into disrepute, which has prompted the authorities to think of novel ways of controlling journalists. : : : : : : : The military has long integrated into its operational planning the principles of the information society and of a world wrapped into a tight network of infor- mation media. Controlling the way war is represented has acquired the same strategic importance as the ability to disrupt the enemies’ communications.1 The “rescue” of Private Jessica Lynch, which was filmed by the US Army on 1 April 2003, is a textbook example, even if the lies surrounding Private Lynch’s * This contribution is an adapted version of the article “Guerre et médias: permanences et mutations”, Raisons politiques, N° 13, février 2004, pp. -

Confederate Military Records

Confederate Military Records Tracing your ancestor's service in the Confederate army during the Civil War can be a very rewarding part of genealogical research. As the first state to secede from the Union, South Carolina has had an abiding interest in preserving a record of the Palmetto State's service to the Confederate States of America. Today, the South Carolina Department of Archives and History continues that tradition with its collection of Confederate military records. The records listed below, consisting of National Archives' microfilm and original documents from various state agencies, are the primary tools for tracing your ancestor's Confederate service. A Guide to Civil War Records, a more in depth description of our Civil War collection is available from our publications branch. All the records listed below are available to the public in the SC Archives' Reference Room. For your ease, we have broken the list into two groups: military service records and veteran benefit records. Military service records • National Archives, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Serving from South Carolina, 1861-1865, microfilm: M267. The compiled service records microfilm is the Department's most comprehensive and widely used set of Confederate records. These service records are based on the original muster rolls, and other documents captured or collected by the Union Army and the War Department during and after the war. They were created by the War Department in 1903 because of the deteriorating condition of the original documents. The service records include information related to unit, rank, enlistment, dates of service, wounds, capture, and death in service. -

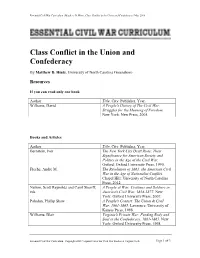

Class Conflict in the Union and Confederacy | May 2018

Essential Civil War Curriculum | Matthew D. Hintz, Class Conflict in the Union and Confederacy | May 2018 Class Conflict in the Union and Confederacy By Matthew D. Hintz, University of North Carolina Greensboro Resources If you can read only one book Author Title. City: Publisher, Year. Williams, David A People's History of The Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom. New York: New Press, 2005. Books and Articles Author Title. City: Publisher, Year. Bernstein, Iver The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990. Fleche, Andre M. The Revolution of 1861: the American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. Nelson, Scott Reynolds and Carol Sheriff, A People at War: Civilians and Soldiers in eds. America's Civil War, 1854-1877. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. Paludan, Phillip Shaw A People's Contest: The Union & Civil War, 1861-1865. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1988. Williams, Blair Virginia's Private War: Feeding Body and Soul in the Confederacy, 1861-1865. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. Essential Civil War Curriculum | Copyright 2018 Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech Page 1 of 3 Essential Civil War Curriculum | Matthew D. Hintz, Class Conflict in the Union and Confederacy | May 2018 Williams, David Bitterly Divided: The South's Inner Civil War. New York: New Press, 2008. Organizations Web Resources URL Name and description http://zinnedproject.org/materials/civil- This is a teaching aid and essay covering war-and-class-conflict/ Chapter 10 of David Williams’ A People's History of The Civil War. -

Introduction: Cyber and the Changing Face of War

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 4-2015 Introduction: Cyber and the Changing Face of War Claire Oakes Finkelstein University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Kevin H. Govern Ave Maria School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Computer Law Commons, International Law Commons, International Relations Commons, Internet Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Studies Commons Repository Citation Finkelstein, Claire Oakes and Govern, Kevin H., "Introduction: Cyber and the Changing Face of War" (2015). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 1566. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1566 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction Cyber and the Changing Face of War Claire Finkelstein and Kevin Govern I. War and Technological Change In 2012, journalist David Sanger reported that the United States, in conjunction with Israel, had unleashed a massive virus into the computer system of the Iranian nuclear reactor at Natanz, where the Iranians were engaged in enriching uranium for use in nuclear weaponry.1 Operation "Olympic Games" was conceived as an alternative to a kinetic attack on Iran's nuclear facilities. It was the firstma jor offensive use of America's cyberwar capacity, but it was seen as justified because of the importance of preempt ing Iran's development of nuclear weapons. -

Civil War 150 Action Plan

Midwest Regional Office Civil War Sesquicentennial National Park Service 2011-2015 U.S. Department of the Interior Civil War to Civil Rights An Action Plan for the Midwest Region of the National Park Service to Commemorate the Sesquicentennial of America’s Civil War May 2009 Abraham Lincoln, 1860. Library of Congress. Old Courthouse in St. Louis. NPS Photo Front cover: On the Battery by Andy Thomas. The painting depicts the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas. 1 National Park Service Table of Contents Preface 3 Introduction 5 Who Is Included? 7 Why a Plan for this Area? 9 Recommendations 12 Proposed Events and Activities: 13 Interpretation/Education 14 Resource Preservation and Enhancement 15 Appendices Appendix A - Planning Meeting Participants 17 Appendix B - Proposed Events and Activities 19 Appendix C - Current Events/Activities/Projects in Planning Stages 25 Appendix D - List of Midwest Region Park Units by Theme 29 U.S. Colored Troop soldiers mustering out at Little Rock, Arkansas. Library of Congress. National Park Service 2 I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Abraham Lincoln1 The struggle for freedom…of which the Civil War was but a bloody chapter, continues throughout our land today. The courage and heroism of Negro citizens at Montgomery, Little Rock, New Orleans, Prince Edward County, and Jackson, Mississippi is only a further effort to affirm that democratic heritage so painfully won, in part, upon the grassy battlefields of Antietam, Lookout Mountain, and Gettysburg. -

Introduction to Western Philosophy the Ethics of War and Peace—1

Introduction to Western Philosophy The Ethics of War and Peace—1 Here a couple of summaries of just war theory. The first is from An Encyclopedia of War and Ethics and the second is an online source from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. I. From An Encyclopedia of War and Ethics: account of war in which grounds for moral restraint in JUST WAR. The concept of just war has been a part war are presented. of Western culture from its beginnings. Written The fiercely independent city-states of the accounts of war invariably include efforts to explain, ancient Greeks were consolidated in the conquest of defend, condone, or otherwise justify making war. Alexander the Great, but the widest military Groups seem virtually incapable of mass armed domination of the Mediterranean world and Europe violence in the absence of reasons for seeing their came as the Roman Empire swallowed the Greek cause to be in the right. Throughout history, nations world. From the end of the 2nd century until the fall and leaders assert their righteousness as participants of Imperial Rome at the close of the 5th century, the in war while questioning that of their enemies. empire was constantly at war. While the early The long tradition of expecting and providing Christian church embraced pacifism to the point of moral justifications for war and acts of war has nonresistence despite Roman persecution of continued, despite the absence of clearly universal Christians, church and state united in embracing a value standards by which such judgments are made. notion of just war after Emperor Constantine's In fact there is no consensus about value standards to conversion in 313.