Faculty Research Working Papers Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Mmar26 Match

The NAB Convention: Caught up in the currents of change BroadcastingThe newsweekly of broadcasting and allied arts mMar26Our 48th Year 1979 The Peifect Match. KSTP -TV Minneapolis /St. Paul pñ 0.) Oc Op p X -4/3 ó On Monday, March 5, KSTP -TV became an ABC mz rH Television Network affiliate. More than 45 of the most popular m m° ca network shows have now joined the nation's leading p N news station. m vl co A division of Hubbard Broadcasting, Inc. For more information, call KSTP -TVs Jim Blake, General Sales Manager, at 612/645 -2724. or your nearest Petry office. 1-1 C Source: Prbitron Nov. 78 bp 50 ADIs. Audience ratings are estimates only and subject to the D A limitations of said report. ASCAP, FROM LEGENDS TO SUPERSTARS Since ASCAP was founded in 1914, over those changes are all reflected in the di- 22,000 songwriters and composers have versity and depth of ASCAP's repertory. joined. From Standards, to Rock, to Country, to The list reads like a Who's Who of the Jazz, to MOR, to Disco, to R &B, to Soul, songwriting business. (It's only a lack of to Gospel, to Symphonic, ASCAP has pro- space that limits us to mentioning but a vided the outstanding songwriting talent tiny portion of ASCAP's membership.) of each era not only to the broadcasters In the past 65 years music has gone of America but to the people who tune in. through some very radical changes, but At ASCAP, we've always had the greats. -

A New Magazine Prospectus Informed by a Historical Review and Qualitative Study on the Media Uses of Mormon Women

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-03-17 Time Out for Women Magazine: A New Magazine Prospectus Informed by a Historical Review and Qualitative Study on the Media Uses of Mormon Women Maurianne Dunn Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Dunn, Maurianne, "Time Out for Women Magazine: A New Magazine Prospectus Informed by a Historical Review and Qualitative Study on the Media Uses of Mormon Women" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2962. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2962 This Selected Project is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Time Out for Women Magazine: A New Magazine Prospectus Informed by a Historical Review and Qualitative Study on the Media Uses of Mormon Women Maurianne Dunn A selected project submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Quint Randle, chair Sherry Baker Tom Robinson Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2011 Copyright © 2011 Maurianne Dunn All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Time Out for Women Magazine: A New Magazine Prospectus Informed by a Historical Review and Qualitative Study on the Media Uses of Mormon Women Maurianne Dunn Department of Communications, BYU Master of Arts This project uses a qualitative research approach to understanding Mormon women‘s uses and gratifications of magazines. -

Chicago Sun‐Times, 1994

Soothsay What? Sure Things for '95 Chicago Sun‐Times December 30, 1994 Some things everyone knows. The Oscars are March 27. "Kiss of 8. In an effort to attract a younger audience, WGN‐AM (720) the Spider Woman" is May 18. Taste of Chicago starts June 24. tries to hire Jonathon Brandmeier, Kevin Matthews or Danny And "M.A.N.T.I.S." can't last much longer. Bonaduce from WLUP‐FM (97.9). Instead, WGN settles for bringing back Eddie Schwartz. But the obvious isn't good enough for WeekendPlus. It's impossible to keep up on this town's activities and 9. No‐Zima Zones. entertainment without doing a little extrapolating. So we've gazed into the future to make some educated guesses about 10. Lili Taylor stars as a hip jazz club operator, Brad Pitt is a what to expect in the year ahead. And you ‐ lucky you ‐ get to yuppie entrepreneur out to get her evicted so he can install a read them: computer emporium, and Ethan Hawke is a community activist planting smoke bombs in "Wicker Park." The romantic comedy‐ 1. Despite an elaborate nationwide talent hunt in urban drama boasts shared music tracks by Veruca Salt and Red Red playgrounds, producers of the "Hoop Dreams" dramatic remake Meat. end up recruiting actors from Hollywood's home turf. Jaleel White will play the mercurial Arthur Agee, with Sean Nelson 11. Chamber orchestras call a one‐year moratorium on Vivaldi's ("Fresh") as hype victim William Gates. Also cast: Danny Aiello as "Four Seasons." Coach Gene Pingatore, Tommy Lee Jones as Bobby Knight, Richard Pryor as Arthur's dad, Natalie Cole and Marsha Warfield 12. -

CALIFORNIA's RIGHT of REMOVAL: Recall Politics in the Modern

CALIFORNIA’S RIGHT OF REMOVAL: Recall Politics in the Modern Era DAVID L. SCHECTER, PHD Department of Political Science California State University, Fresno ABSTRACT This article compares the first gubernatorial recall of 1921 with the second such recall of 2003. North Dakota Governor Lynn J. Frazier had always been a footnote in history with his removal from office over 80 years ago, but much can be learned by systematically comparing the first recall campaign with the whirlwind campaign sur- rounding the demise of California Governor Gray Davis and the rise of political neo- phyte Arnold Schwarzenegger. An initial review of the Progressive period is given, followed by an in-depth analysis of America’s first recall, which occurred in the City of Los Angeles in 1903. The article then moves through a detailed discussion of the 1921 campaign to oust Frazier. This first recall is then compared and contrasted with the 2003 California governor’s race. The article concludes with a theoretical discussion of the power of the recall provision and how it may be applied to senior executives in California and elsewhere in the future. This “right of removal” has been both a threat to gubernatorial power and a tool for citizen activism. Imagine a political race where a recently reelected governor faces a tremendous state- wide budget crisis, a well-organized and financially strong opposition, and plunging sup- port from a cynical and frustrated electorate. Adding to this incumbent’s problems, the state is one of only a handful with a rarely used recall provision in its Constitution that some opponents, still bitter from the last race the previous November, plan to exploit. -

Gary Coleman

The Fayetteville Press Newspaper June 2010 Edition Page 11 OBITUARY PAGE Bryan Keith Farr Gary Coleman Gary Coleman, the adorable, pint-sized child star of the smash 1970s TV sitcom “Diff’rent Bryan Keith Farr was the third of four children born to James and Laurie Oliver on the 22nd of Strokes” who spent the rest of his life struggling on Hollywood’s D-list, died Friday after suffering a November, 1988 in Fort Benning, Georgia. He departed this life on May 19th ,2010 . brain hemorrhage. He was 42. Services were held at the R.L. Douglas Cape Fear Conference “B” Headquarters United Ameri- Mr. Coleman was taken off life support and died with family and friends at his side, Utah Valley can Free Will Baptist Church, Raeford N.C. Reverend George Campbell officiating. Regional Medical Center spokeswoman Janet Frank said. Bryan spent most of his life in Fayetteville, North Carolina. He went to school in Fayetteville Mr. Coleman suffered the brain hemorrhage Wednesday at his Santaquin home, 55 miles south graduating from Seventy First High School in the class of 2007. He attended Sanford Community of Salt Lake City. College, in Sanford, North Carolina where he studied telecommunications. A statement from the family said he was conscious and lucid until midday Thursday, when his Bryan joint First Baptist Church of Catron, Missouri at an early age but would move his member- condition worsened and he slipped into unconsciousness. Mr. Coleman was then placed on life ship to Rock Hill Missionary Baptist Church where he would remain throughout the rest of his life. -

Childrenls Diabetes Foundation at Denver

children’s diabetes foundaTION At denver — WINTER 2012 All Carousel of Hope photos: © Berliner Studio All Carousel he elegant room at the beautiful Beverly Hilton T was crowded with nearly one thousand guests for The 26th Carousel of Hope Ball in Beverly Hills, California on October 20. As always The Carousel of Hope was chaired by Barbara Davis. George Clooney, the Brass Ring Award honoree for his humanitarian work and his incomparable talent as an actor and filmmaker, was presented the award by Shirley MacLaine. (Continued on Page 10) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. George Clooney, Honoree The Carousel of Hope 2. Barbara Davis, Clive Davis 3. Shane Hendryson, Dana Davis 4. Jackie Collins, Barbara Davis, Joan Collins 5. Richard Perry, Barbara Davis, Jane Fonda ON THE COVER 1. Shirley MacLaine, George Clooney 2. David Foster 3. Neil Diamond, George Clooney 4. Neil Diamond 5. Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds, David Foster, Barbara Davis, George Clooney 2 The Carousel of Hope 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Nancy Davis, Ken Rickel, Mariella & Isabella Rickel 2. Neil Diamond, Quincy Jones, Clive Davis, Berry Gordy 3. Brad & Cassandra Grey, Carole & Bob Daly 4. Barbara Davis, George Clooney, Stacy Keibler 5. Joanna & Sidney Poitier, George Clooney 3 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Gayle King, Jay & Mavis Leno 6. 2. Corinna Fields, Ryan O’Neal 3. Neil Diamond, George Clooney 4. Jim Gianopulos 5. Jerry & Linda Bruckheimer The Carousel of Hope 6. Nicole “Nikki” Pantenburg, Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds, Terry & Jane Semel 4 The Carousel of Hope 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 1. Jolene & George Schlatter, George Clooney 2. -

STATEWIDE SPECIAL ELECTION OCTOBER 7, 2003 Results As of 10/13/2003 at 4:03 PM Official Certified Results

STATEWIDE SPECIAL ELECTION OCTOBER 7, 2003 Results as of 10/13/2003 at 4:03 PM Official Certified Results PRECINCTS COUNTED - TOTAL Completed Precincts: 48 of 48 Reg/Turnout Percentage REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL 46,600 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL 23,490 50.41% Shall Gray Davis Be Recalled? Vote For: 1 Completed Precincts: 48 of 48 Candidate Name Vote Count Percentage YES 15,573 71.58% NO 6,184 28.42% Candidates To Succeed Gray Davis Vote For: 1 Completed Precincts: 48 of 48 Candidate Name Vote Count Percentage REP ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER 12,539 56.55% DEM CRUZ M. BUSTAMANTE 5,174 23.33% REP TOM MCCLINTOCK 3,835 17.30% GRN PETER MIGUEL CAMEJO 155 0.70% IND ARIANNA HUFFINGTON 40 0.18% REP PETER V. UEBERROTH 31 0.14% IND GARY COLEMAN 28 0.13% REP BILL SIMON 24 0.11% IND GEORGE B. SCHWARTZMAN 19 0.09% IND MARY "MARY CAREY" COOK 18 0.08% DEM PAUL "CHIP" MAILANDER 17 0.08% DEM LAWRENCE STEVEN STRAUSS 15 0.07% DEM LARRY FLYNT 13 0.06% IND BOB MCCLAIN 12 0.05% IND JOHN CHRISTOPHER BURTON 10 0.05% IND LEO GALLAGHER 10 0.05% DEM DAVID LAUGHING HORSE ROBINSON 9 0.04% REP DENNIS DUGGAN MCMAHON 8 0.04% DEM JONATHAN MILLER 8 0.04% IND BADI BADIOZAMANI 8 0.04% DEM EDWARD "ED" KENNEDY 8 0.04% DEM BRUCE MARGOLIN 8 0.04% DEM FRANK A. MACALUSO, JR. 8 0.04% REP MIKE MCNEILLY 7 0.03% REP CHERYL BLY-CHESTER 7 0.03% DEM GARRETT GRUENER 7 0.03% IND MIKE P. -

Fame Attack : the Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences

Rojek, Chris. "Celebrity and Sickness." Fame Attack: The Inflation of Celebrity and Its Consequences. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 35–57. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 3 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849661386.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 3 October 2021, 06:08 UTC. Copyright © Chris Rojek 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 Celebrity and Sickness o speak of celebrity ‘craving’ implies both a compulsion to be famous on the part of would-be celebrities and an emotional dependence upon fame in the celebrity fl ock. Psychologists argue that, today, pronounced and seductive types of celebrity craving are unprecedented. The risks that they pose to ordinary men and women are unparalleled. TThe Internet, satellite television and show-business magazines make public news and private details of celebrity lives ubiquitous and offer round-the-clock access. Exposure to celebrity culture is instant and perpetual. With perpetual exposure, there are, of course, gains, but also appreciable risks and high costs. For example, Madonna’s humanitarian work in Malawi suffered a serious blow when an audit report (2011) revealed that $3.8 m (£2.4 m) had been spent on a prestigious academy for underprivileged girls that had never been built. The report alleged outlandish expenditures on salaries, cars, offi ce space, golf course membership and free housing. The controversy led to the resignation of the charity’s executive director, Philippe van den Bossche, the partner of Madonna’s personal trainer. -

The Coogan Law

The Coogan Law By Trevor Shor Writing 50 Professor Genova December 2, 2009 The Coogan Law 2 The Coogan Law I. Introduction to the Coogan Law On October 26, 1914, a child was born that would eventually become the most famous child actor of the 1920s—his name was John Leslie Coogan, Jr., or ‘Jackie’ Coogan. His rise to stardom came as no surprise, as both his mother and father were well-known vaudeville performers. During one of their performances, the Coogans brought young Jackie out onto the stage to perform a small dance number. The audience instantly fell in love with this child, particularly the famous comedian and actor, Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin immediately signed the child on for his film The Kid, in which Coogan played Chaplin’s son. The film had major success and was followed by several other projects, making nine-year-old Jackie Coogan “one of the biggest stars in Hollywood” (Grauer, 2000, p. 50). As his career continued to grow, his paychecks started to grow as well, and by 1924, Coogan’s wealth had accrued to almost $2 million from his film career alone (Goldman, 2001, p. 27). By the time his childhood fame started to decline, Jackie Coogan had made about $4 million; however, upon reaching adulthood, he would learn that his mother had squandered almost his entire fortune. After unsuccessfully fighting for his earnings, Coogan filed a lawsuit against his mother and new stepfather, Arthur Bernstein, to recoup his lost earnings in 1938. Unfortunately, Coogan’s fortune had shrunken to a mere $250,000 at the time of the lawsuit, and when the case was finally settled, he received less than half of that amount (Grauer, 2000, p. -

2020 Spotlight Acting Semifinal Panel

2020 Spotlight Acting Semifinal Panel Daniel Guzman has appeared on Broadway in Cyrano, The Musical and Les Miserables as well as having appeared in national and international tours including Camelot, Jesus Christ Superstar, Cats, Les Miserables, Guys and Dolls, Sweet Charity, Evita, West Side Story, Man of La Mancha, The King and I, and A Chorus Line, among others. Mr. Guzman has performed several shows at The Hollywood Bowl, highlights which include the honor of singing for Stephen Sondheim at his 75th birthday concert, as well as performing in Les Miserables as Grantaire. Mr. Guzman executive produced the feature film First Comes Like and can be seen in the new series the for his production company Laughing House Productions, The Secret Office, both which are available online at Amazon.com. His musical SAVE THE GIRL Is now being work shopped and hopefully will have a full production soon. Gai Jones is the Vice President of the Educational Theatre Association (EdTA) Governing Board which sets Policy for the two million members of the International Thespian Society as the honor society for middle and high school students; Educational Theatre Foundation (ETF) Board Member; Vice President of Membership for California Educational Theatre Association (CETA); Director of Advocacy for Drama Teachers Association of Southern California (DTASC). She has served as CETA President and CA State Thespian Chapter Director. She is the recipient of the EdTA President’s Award, inductee into the CA Thespian and EdTA’s Hall of Fame. She earned her MA in Theatre from CSUF and I’d the Founder of California Youth in Theatre. -

June,09,2016

Celebrating 125 years as Davis County’s news source Davis County high school grads The honored Davis Clipper ON C1 75 cents VOL. 124 NO. 67 THURSDAY, JUNE 9, 2016 Groundbreaking held for new Bountiful Museum BY JENNIFFER WARDELL throughout this summer and fall, held its for most of my adult life.” [email protected] official groundbreaking last week in the area Commission members have been working behind the historic home. for years to raise the funds for the new That area will serve as the space for a museum, testing out various properties along BOUNTIFUL—Old shovels planned 1,000 square foot expansion, which Main Street and throughout Bountiful before will be added to the original 1890s home to the city decided to purchase Smedley Manor. and fresh radishes helped mark a create a permanent space that the Bountiful Still, Bountiful Mayor Randy Lewis felt it was brand-new future for the Bountiful Historical Commission has been waiting worth the wait. decades to bring to life. “It’s been done the right way,” he said. “It’s Museum. “This has been a long struggle for a lot of the right place for the right price, and it’s The museum, which will officially move into us,” said Bountiful Historical Commission Smedley Manor on 300 North and Main Street Chair Tom Tolman. “I’ve been working on this n See “MUSEUM” p. A5 Free concerts now in Layton JENNIFFER WARDELL, D3 Raising hope for the future Goat project helps refugees find their footing in Utah. LOUISE R. SHAW, D1 Teams for Tour of Utah Sixteen teams are finalized for this year’s event. -

Master Summary Report

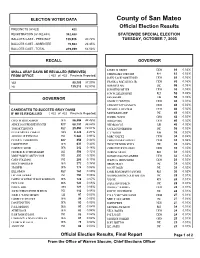

ELECTION VOTER DATA County of San Mateo Official Election Results PRECINCTS (of 422) 422 REGISTRATION (of 342,488) 342,488 STATEWIDE SPECIAL ELECTION BALLOTS CAST - PRECINCT 139,535 40.74% TUESDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2003 BALLOTS CAST - ABSENTEE 79,964 23.35% BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL 219,499 64.09% RECALL GOVERNOR JAMES H. GREEN DEM 65 0.03% SHALL GRAY DAVIS BE RECALLED (REMOVED) CHERYL BLY-CHESTER REP 62 0.03% FROM OFFICE ( 422 of 422 Precincts Reported) JOHN "JACK" MORTENSEN DEM 61 0.03% YES 80,109 37.20% FRANK A. MACALUSO, JR. DEM 60 0.03% NO 135,210 62.80% BOB MCCLAIN IND 56 0.03% JONATHAN MILLER DEM 53 0.03% JON W. ZELLHOEFER REP 52 0.03% GOVERNOR KEN HAMIDI LIB 50 0.03% LINGEL H. WINTERS DEM 48 0.02% EDWARD "ED" KENNEDY DEM 48 0.02% CANDIDATES TO SUCCEED GRAY DAVIS MICHAEL J. WOZNIAK DEM 46 0.02% IF HE IS RECALLED ( 422 of 422 Precincts Reported) MOHAMMAD ARIF IND 45 0.02% DANIEL WATTS GRN 42 0.02% CRUZ M. BUSTAMANTE DEM 86,854 44.49% DIANA FOSS DEM 40 0.02% ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER REP 68,191 34.93% NED ROSCOE LIB 40 0.02% TOM MCCLINTOCK REP 23,454 12.01% JACK LOYD GRISHAM IND 36 0.02% PETER MIGUEL CAMEJO GRN 8,224 4.21% C.T. WEBER P&F 35 0.02% ARIANNA HUFFINGTON IND 1,584 0.81% MARC VALDEZ DEM 34 0.02% PETER V. UEBERROTH REP 858 0.44% CHRISTOPHER SPROUL DEM 33 0.02% LARRY FLYNT DEM 635 0.33% TREK THUNDER KELLY IND 33 0.02% CALVIN Y.