Cognitive Processes of Discourse Comprehension in Children and Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scouting Games. 61 Horse and Rider 54 1

The MacScouter's Big Book of Games Volume 2: Games for Older Scouts Compiled by Gary Hendra and Gary Yerkes www.macscouter.com/Games Table of Contents Title Page Title Page Introduction 1 Radio Isotope 11 Introduction to Camp Games for Older Rat Trap Race 12 Scouts 1 Reactor Transporter 12 Tripod Lashing 12 Camp Games for Older Scouts 2 Map Symbol Relay 12 Flying Saucer Kim's 2 Height Measuring 12 Pack Relay 2 Nature Kim's Game 12 Sloppy Camp 2 Bombing The Camp 13 Tent Pitching 2 Invisible Kim's 13 Tent Strik'n Contest 2 Kim's Game 13 Remote Clove Hitch 3 Candle Relay 13 Compass Course 3 Lifeline Relay 13 Compass Facing 3 Spoon Race 14 Map Orienteering 3 Wet T-Shirt Relay 14 Flapjack Flipping 3 Capture The Flag 14 Bow Saw Relay 3 Crossing The Gap 14 Match Lighting 4 Scavenger Hunt Games 15 String Burning Race 4 Scouting Scavenger Hunt 15 Water Boiling Race 4 Demonstrations 15 Bandage Relay 4 Space Age Technology 16 Firemans Drag Relay 4 Machines 16 Stretcher Race 4 Camera 16 Two-Man Carry Race 5 One is One 16 British Bulldog 5 Sensational 16 Catch Ten 5 One Square 16 Caterpillar Race 5 Tape Recorder 17 Crows And Cranes 5 Elephant Roll 6 Water Games 18 Granny's Footsteps 6 A Little Inconvenience 18 Guard The Fort 6 Slash hike 18 Hit The Can 6 Monster Relay 18 Island Hopping 6 Save the Insulin 19 Jack's Alive 7 Marathon Obstacle Race 19 Jump The Shot 7 Punctured Drum 19 Lassoing The Steer 7 Floating Fire Bombardment 19 Luck Relay 7 Mystery Meal 19 Pocket Rope 7 Operation Neptune 19 Ring On A String 8 Pyjama Relay 20 Shoot The Gap 8 Candle -

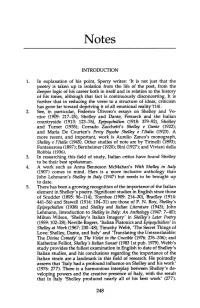

INTRODUCTION 1. in Explanation of His Point, Sperry Writes: 'It Is Not Just

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. In explanation of his point, Sperry writes: 'It is not just that the poetry is taken up in isolation from the life of the poet, from the deeper logic of his career both in itself and in relation to the history of his times, although that fact is continuously disconcerting. It is further that in reducing the verse to a structure of ideas, criticism has gone far toward depriving it of all emotional reality'(14). 2. See, in particular, Federico Olivero's essays on Shelley and Ve nice (1909: 217-25), Shelley and Dante, Petrarch and the Italian countryside (1913: 123-76), Epipsychidion (1918: 379-92), Shelley and Turner (1935); Corrado Zacchetti's Shelley e Dante (1922); and Maria De Courten's Percy Bysshe Shelley e l'Italia (1923). A more recent, and important, work is Aurelio Zanco's monograph, Shelley e l'Italia (1945). Other studies of note are by Tirinelli (1893); Fontanarosa (1897); Bernheimer (1920); Bini (1927); and Viviani della Robbia (1936). 3. In researching this field of study, Italian critics have found Shelley to be their best spokesman. 4. A work such as Anna Benneson McMahan's With Shelley in Italy (1907) comes to mind. Hers is a more inclusive anthology than John Lehmann's Shelley in Italy (1947) but needs to be brought up to date. 5. There has been a growing recognition of the importance of the Italian element in Shelley's poetry. Significant studies in English since those of Scudder (1895: 96-114), Toynbee (1909: 214-30), Bradley (1914: 441-56) and Stawell (1914: 104-31) are those of P. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Food Security in Ancestral Tewa Coalescent Communities: the Zooarchaeology of Sapa'owingeh in the Northern Rio Grande, New Mexico

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Anthropology Theses and Dissertations Anthropology Spring 5-15-2021 Food Security in Ancestral Tewa Coalescent Communities: The Zooarchaeology of Sapa'owingeh in the Northern Rio Grande, New Mexico Rachel Burger [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Burger, Rachel, "Food Security in Ancestral Tewa Coalescent Communities: The Zooarchaeology of Sapa'owingeh in the Northern Rio Grande, New Mexico" (2021). Anthropology Theses and Dissertations. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_anthropology_etds/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. FOOD SECURITY IN ANCESTRAL TEWA COALESCENT COMMUNITIES: THE ZOOARCHAEOLOGY OF SAPA’OWINGEH IN THE NORTHERN RIO GRANDE, NEW MEXICO Approved by: ___________________________________ B. Sunday Eiselt, Associate Professor Southern Methodist University ___________________________________ Samuel G. Duwe, Assistant Professor University of Oklahoma ___________________________________ Karen D. Lupo, Professor Southern Methodist University ___________________________________ Christopher I. Roos, Professor Southern Methodist University FOOD SECURITY IN ANCESTRAL TEWA COALESCENT COMMUNITIES: THE ZOOARCHAEOLOGY OF SAPA’OWINGEH IN THE NORTHERN RIO GRANDE, NEW MEXICO A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a Major in Anthropology by Rachel M. Burger B.A. Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville M.A., Anthropology, Southern Methodist University May 15, 2021 Copyright (2021) Rachel M. -

\0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 X 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3

... \0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 x 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3 ... \0-9\1,000,000 ... \0-9\10 Pin ... \0-9\10... Knockout! ... \0-9\100 Meter Dash ... \0-9\100 Mile Race ... \0-9\100,000 Pyramid, The ... \0-9\1000 Miglia Volume I - 1927-1933 ... \0-9\1000 Miler ... \0-9\1000 Miler v2.0 ... \0-9\1000 Miles ... \0-9\10000 Meters ... \0-9\10-Pin Bowling ... \0-9\10th Frame_001 ... \0-9\10th Frame_002 ... \0-9\1-3-5-7 ... \0-9\14-15 Puzzle, The ... \0-9\15 Pietnastka ... \0-9\15 Solitaire ... \0-9\15-Puzzle, The ... \0-9\17 und 04 ... \0-9\17 und 4 ... \0-9\17+4_001 ... \0-9\17+4_002 ... \0-9\17+4_003 ... \0-9\17+4_004 ... \0-9\1789 ... \0-9\18 Uhren ... \0-9\180 ... \0-9\19 Part One - Boot Camp ... \0-9\1942_001 ... \0-9\1942_002 ... \0-9\1942_003 ... \0-9\1943 - One Year After ... \0-9\1943 - The Battle of Midway ... \0-9\1944 ... \0-9\1948 ... \0-9\1985 ... \0-9\1985 - The Day After ... \0-9\1991 World Cup Knockout, The ... \0-9\1994 - Ten Years After ... \0-9\1st Division Manager ... \0-9\2 Worms War ... \0-9\20 Tons ... \0-9\20.000 Meilen unter dem Meer ... \0-9\2001 ... \0-9\2010 ... \0-9\21 ... \0-9\2112 - The Battle for Planet Earth ... \0-9\221B Baker Street ... \0-9\23 Matches .. -

Eagle Imagery in Jewish Relief Sculpture of Late Ancient Palestine: Survey and Interpretation

EAGLE IMAGERY IN JEWISH RELIEF SCULPTURE OF LATE ANCIENT PALESTINE: SURVEY AND INTERPRETATION Steven H. Werlin A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Religious Studies Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Jodi Magness Reader: Eric M. Meyers Reader: Zlatko Plese © 2006 Steven H. Werlin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT STEVEN H. WERLIN: Eagle Imagery in Jewish Relief Sculpture of Late Ancient Palestine: Survey and Interpretation (Under the direction of Jodi Magness) The following study examines the image of the eagle in the architectural relief sculpture of Palestinian synagogues as well as on Jewish sarcophagi. The buildings and sarcophagi on which these objects were displayed are dated between the third and sixth century C.E. Chapter one introduces the topic by presenting some general background to the state of research and by defining relevant terms for the study. Chapter two presents the primary evidence in the form of a rudimentary catalogue. Chapter three examines the so-called “Eagle Incident” described by the ancient historian, Josephus, in War 1.648-55 and Antiq. 17.151-63. Chapter four seeks to understand the meaning of the eagle-symbol within the literature familiar to Jews of late ancient Palestine. Chapter five presents the author’s interpretation of the eagle-symbol in both the sculptural remains and literary references. It considers the relationship of the image and meaning to Near Eastern and Byzantine art in light of the religious trends in late ancient Jewish society. -

LETTER from the PRESIDENT Merlin

winter 2008 - 2009 Adopt a Wild Raptor! CONTRIBUTE TO RVRI THROUGH OUR ‘ADOPT A RAPTOR PROGRAM’ When you adopt a raptor, you will receive a packet which includes an adoption certificate specific to your individual bird with band number, wing tag (Golden Eagle only), age, sex, size and when and where it was banded. You will also be notified of any follow-up information regarding re-sightings, re-capture and recoveries. Furthermore, you will get a 4 x 6 color photo of your adopted bird and an informative Natural History fact sheet. P. O. BOX 4323 MISSOULA, MT 59806 (406) 258-6813 AVAILABLE RAPTORS [email protected] www.raptorview.org Sharp-shinned Hawk........................................................... $25 American Kestrel ................................................................ $25 Cooper’s Hawk ................................................................... $35 Northern Harrier .................................................................. $35 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT Merlin ................................................................................... $45 Prairie Falcon ....................................................................... $45 Red-tailed Hawk ................................................................. $50 ello everyone and welcome to our fourth annual of Missoula, Mont. A big thanks to friends and colleagues, newsletter. We had a productive year in 2008, Dr. Erick Greene, with the University of Montana, and Kate Rough-legged Hawk ......................................................... -

The American Legion Monthly Is the Official Publication of the American Legion and the American Legion Auxiliary and Is Owned Exclusively by the American Legion

25 Cents October -1926 M E RI CAN EGION Beginning HOW RED IS AMERICA ? — By WILL IRWIN . "MAKE" THE BAND - share the highest honors f . ZHE winning kick sails between ress, make practice real fun. World- m the goal posts ... thefinalwhis- famous professionals choose Conns ^/ tie sounds ... surging down the for their superior quality. In 50 years field comes the frenzied victory dance building fine instruments Conn has won highest honors at world exposi- ... at the head of it marches the band! tions. With all their exclusive features In the LegionPost, just as in the school Conns cost no more ! and college, Bandsmen share the high- Every Legion Post should have a band, est honors. the winning band at When orchestra or both. We'll help you or- thePhiladelphia convention heads the ganize, with definite, detai led plans, in- parade Broad Street, the down mem- cluding easy financing. Commanders, bers will have the spotlight in the con- Adjutants, interested members should vention's headline home, as event. At write to our Band Service Department well as at state and national conven- for details; no obligation is involved. tions, the Band is an important feature of Post and civic functions. Free Trial, Easy Payments. Choose any Conn for trial in your own home. With a Conn instrument you can join Send coupon now for details. The a band in a very short time. Exclusive, Conn dealer in your community can easy-playing features enable rapid prog- help you get started; see him. C. G. CONN, LTD., 1003 Conn Dldg., Elkhart, Ind. -

The Barbados Stud Book Containing Pedigrees Of

THE BARBADOS STUD BOOK CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES etc., etc. From the earliest accounts to the year 2019 inclusive in THIRTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THIRTEEN Published by the Barbados Turf Club Garrison St. Michael Barbados 2021 (All rights reserved) Page No Table of Contents ELIGIBILITY ............................................................................................................................................. iii STATISTICAL ANALYSIS ....................................................................................................................... iii COAT COLOURS ...................................................................................................................................... iv ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................... iv INDEX TO WHOLE.................................................................................................................................... v BROODMARES AND THEIR PRODUCE .............................................................................................. 1 SIRES .......................................................................................................................................................... 24 ERRATA AND ADDENDA ...................................................................................................................... 28 ERRATA ................................................................................................................................................ -

Hoyle Solitaire Rulebook

SIERRA Tutorial Introduction The following information provides an overview of how to use Hoyle Solitaire. Main Menu Screen The Main Menu screen will allow you to select from “PLAY GAME”, “GAME CREDITS”, “ABOUT HOYLE”, “TUTORIAL”, “GLOSSARY”, and “QUIT.” The Glossary defines standard terms used in solitaire. Game Selection Screen The “PLAY GAME” button places you into the Game Selection screen which lists the 28 solitaire games available. To choose a game, left mouse click on the title of the game you want to play. You can also use the “Tab” and “shift- Tab” keys to cycle forward and backward through the titles; use “Enter” to select the game. The game selection screen will also display a diamond symbol next to any game that has been won. You can hone your card flicking skills by clicking on the “CARD FLICK” icon. Card Flick Whenever you win a game, you will have the opportunity to “Take a Shot” – flicking a card into a “hat”. Successfully flicking a card from a moving hand into a “hat” rewards you with an animation. Left mouse click when you want “your” hand to flick the card. You can hone your card flicking skills by clicking on the “CARD FLICK” button in the Game Selection screen. Watch out! It is quite addicting! Note: If Card Flick performance is slow, turning the background music off may help speed up animations. Solitaire Gameplay Overview In general, a solitaire game begins with cards laid out in a Tableau (original layout). Gameplay begins by clicking on a Stock pile (undealt cards), to turn up new cards as you try to build up Columns of cards which match in rank, color, suit, etc.. -

Vol. 13, No. 6 November 2004

Chantant • Reminiscences • Harmony Music • Promena Evesham Andante • Rosemary (That's for Remembran Pastourelle • Virelai • Sevillana • Une Idylle • Griffinesque • Ga Salut d'Amour • Mot d'AmourElgar • Bizarrerie Society • O Happy Eyes • My Dwelt in a Northern Land • Froissart • Spanish Serenad Capricieuse • Serenade • The Black Knight • Sursum Corda Snow • Fly, Singing ournalBird • From the Bavarian Highlands • The L Life • King Olaf • Imperial March • The Banner of St George • Te and Benedictus • Caractacus • Variations on an Original T (Enigma) • Sea Pictures • Chanson de Nuit • Chanson de Matin • Characteristic Pieces • The Dream of Gerontius • Serenade Ly Pomp and Circumstance • Cockaigne (In London Town) • C Allegro • Grania and Diarmid • May Song • Dream Chil Coronation Ode • Weary Wind of the West • Skizze • Offertoire Apostles • In The South (Alassio) • Introduction and Allegro • Ev Scene • In Smyrna • The Kingdom • Wand of Youth • How Calm Evening • Pleading • Go, Song of Mine • Elegy • Violin Concer minor • Romance • Symphony No 2 • O Hearken Thou • Coro March • Crown of India • Great is the Lord • Cantique • The Makers • Falstaff • Carissima • Sospiri • The Birthright • The Win • Death on the Hills • Give Unto the Lord • Carillon • Polonia • Un dans le Desert • The Starlight Express • Le Drapeau Belge • The of England • The Fringes of the Fleet • The Sanguine Fan • Sonata in E minorNOVEMBER • String Quartet 2004 in E Vol.13,minor •No Piano.6 Quint minor • Cello Concerto in E minor • King Arthur • The Wand E i M h Th H ld B