Changes in Open Defecation in Rural North India: 2014-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bacterial Contamination of Drinking Water Sources in Rural Villages Of

Gwimbi et al. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2019) 24:33 Environmental Health and https://doi.org/10.1186/s12199-019-0790-z Preventive Medicine RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Bacterial contamination of drinking water sources in rural villages of Mohale Basin, Lesotho: exposures through neighbourhood sanitation and hygiene practices Patrick Gwimbi* , Maeti George and Motena Ramphalile Abstract Background: Bacterial contamination of drinking water is a major public health problem in rural areas of sub- Saharan Africa. Unimproved water sources are a major reservoir of Escherichia coli (E. coli) causing severe diarrhoea in humans. This study assessed E. coli counts in drinking water from different sources and their relationship with water source protection status and neighbourhood sanitation and hygiene practices in rural villages of Mohale Basin in Lesotho. Methods: Thirty drinking water sources were purposively sampled and their water analysed for E. coli counts. The types of water sources, their protection status and neighbourhood sanitation and hygiene practices in their proximity were also assessed. E. coli counts in water samples were compared to water source protection status, neighbourhood sanitation, hygiene practices, livestock faeces and latrine proximity to water sources. Results: E. coli counts were found in all water samples and ranged from less than 30 colony-forming units (cfu)/100 ml to 4800 cfu/100 ml in protected sources to 43,500,000 cfu/100 ml in unprotected sources. A significant association between E. coli counts in drinking water samples and lack of water source protection, high prevalence of open defecation (59%, n = 100), unhygienic practices, livestock faeces and latrine detections in proximity to water sources was found in the study (P <0.05). -

As Rich in Beauty As in Historic Sites, North India and Rajasthan Is a Much Visited Region

India P88-135 18/9/06 14:35 Page 92 Rajasthan & The North Introduction As rich in beauty as in historic sites, North India and Rajasthan is a much visited region. Delhi, the entry point for the North can SHOPPING HORSE AND CAMEL SAFARIS take you back with its vibrancy and Specialities include marble inlay work, precious Please contact our reservations team for details. and semi-precious gemstones, embroidered and growth from its Mughal past and British block-printed fabrics, miniature Mughal-style FAIRS & FESTIVALS painting, famous blue pottery, exquisitely carved Get caught up in the excitement of flamboyant rule. The famous Golden Triangle route furniture, costume jewellery, tribal artefacts, and religious festivals celebrated with a special local starts here and takes in Jaipur and then don't forget to get some clothes tailor-made! farvour. onwards to the Taj Mahal at Agra. There’s SHOPPING AREAS Feb - Jaisalmer Desert Festival, Jaisalmer Agra, marble and stoneware inlay work Taj so much to see in the region with Mughal complex, Fatehbad Raod and Sabdar Bazaar. Feb - Taj Mahotsav, Agra influence spreading from Rajasthan in Delhi, Janpath, Lajpat Nagar, Chandini Chowk, Mar - Holi, North India the west to the ornate Hindu temples of Sarojini Nagar and Ajmal Khan Market. Mar - Elephant Festival, Jaipur Khajuraho and Orcha in the east, which Jaipur, Hawa Mahal area, Chowpars for printed Apr - Ganghur Festival, Rajasthan fabrics, Johari Bazaar for jewellery and gems, leads to the holy city of Varanasi where silverware etc. Aug - Sri Krishna Janmasthami, Mathura - Vrindavan pilgrims gather to bathe in the crowded Jodhpur, Sojati Gate and Station area, Tripolia Bazaar, Nai Sarak and Sardar Market. -

ANAL CLEANSING: Lack of Materials Contributes to Disease, Shame, Confusion Questions

ANAL CLEANSING: Lack of materials contributes to disease, shame, confusion Questions Without proper materials for anal cleansing, students desires to wipe and to wash their hands after wiping. and their classmates are at increased risk of acquiring “Sometimes there is feces left on you and your hands diarrheal diseases through hand contamination. The and, say, you have bought doughnuts and shared lack of such materials at schools is a concern. Further- them with someone and then he will eat your dirt… more, latrines can be quickly filled if inadequate mate- and then he is sick and then you feel bad,” said a rials (such as rocks or corncobs) are used by students. grade 7 male from Kamunda. To better understand how anal cleansing can be ef- fectively communicated, SWASH+ researchers wanted Perceived personal risk of disease or illness was men- to know three things: tioned near the end of discussions as a reason to • How do students feel about anal cleansing? clean properly. Cholera was the illness mentioned first, • What materials are best for anal cleansing? and, followed by dysentery, typhoid and nyach (a term for • How much do students know about this area? any STI excluding HIV/AIDS). Emotional factors that motivate students to wipe in- Research clude a desire to avoid shame due to soiled clothing or smelliness. Students also mentioned that ineffective Since 2007, the SWASH+ program has been conduct- cleansing inhibits concentration. “When you smell, you ing research in rural Nyanza Province, Kenya, to assess cannot focus in class,” said a grade 7 female from the impact, sustainability, and scalability of a school- Bunde. -

People's Republic of Bangladesh Country Overview

People's Republic of Bangladesh Country Overview Summary Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in advancing access to water and sanitation services by increasing access to drinking water to 98%1 and reducing open defecation practices to almost zero in 2019 (1.5%2). In 2018 74.8% of the population had a handwashing station with water and soap on their premises3. The major WASH challenge Bangladesh is now facing is to improve practices and quality of WASH services i.e., predominantly water quality and safe disposal of human excreta to fully realize health and wellbeing outcomes for the poorest. In achieving this, the sector also has to overcome climate change impacts affecting the sustainability and continuity and quality of WASH services. According to the SDG Financing Strategy 2017 of General Economic Division, Bangladesh will require additional 11.80 billion dollars to achieve SDG-6 (constant 2015-16 prices) out of which 9.34 billion dollars is required for SDG 6.1 and SDG 6.24. The financial requirement for fiscal year 2017-2018 for SDG 6.1 & SDG 6.2 was 1.31 billion US dollars. Allocation was US$ 0.80 billion dollar and the gap was 0.51 billion US$5. About half of the WASH sector budget allocation for SDG-6 is from the public-sector funds, with private sector contributing 30% and development assistance making up the balance (20%). Government has also expanded the Annual Development Programme (ADP)6 Budget allocations to the sector from US$ 563 million in fiscal year 2017-18 to US$ 1.44 billion in 20018-19. -

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Practices and Challenges During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Odisha, India

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 104(6), 2021, pp. 2264–2274 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.21-0087 Copyright © 2021 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Practices and Challenges during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Odisha, India Valerie Bauza,1* Gloria D. Sclar,1,2 Alokananda Bisoyi,3 Fiona Majorin,4 Apurva Ghugey,5 and Thomas Clasen1 1Gangarosa Department of Environmental Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; 2Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, ¨ Zurich, ¨ Switzerland; 3Independent Consultant, Berhampur, Odisha, India; 4London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom; 5Gram Vikas, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India Abstract. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices emerged as a critical component to controlling and preventing the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. We conducted 131 semistructured phone interviews with households in rural Odisha, India, to understand behavior changes made in WASH practices as a result of the pandemic and challenges that would prevent best practices. Interviews were conducted from May through July 2020 with 73 heads of household, 37 caregivers of children < 5 years old, and 21 members of village water and sanitation committees in villages with community-level piped water and high levels of latrine ownership. The majority of respondents (86%, N = 104) reported a change in their handwashing practice due to COVID-19, typically describing an increase in handwashing frequency, more thorough washing method, and/or use of soap. These improved handwashing practices remained in place a few months after the pandemic began and were often described as a new consistent practice after additional daily actions (such as returning home), suggesting new habit formation. -

World Bank Document

WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM: RESEARCH BRIEF Public Disclosure Authorized Scaling Up Rural Sanitation Investing in the Next Generation: Growing Tall and Smart with Toilets Stopping Open Defecation Improves Children’s Height in Cambodia November 2013 Key Messages Public Disclosure Authorized • The period between 2005 and 2010 witnessed a significant reduction in the number of households openly defecating and an increase in average child height. The improvement in sanitation access likely played a substantial role in increasing average child height over these five years. • Good toilets make good neighbors. The research in Cambodia found that open defecation not only affects one’s own health, but it also affects the health of one’s neighbors. The extent of open defecation in a community is more important for a child’s development than whether the Public Disclosure Authorized child’s household itself openly defecates. INTRODUCTION • Given the importance of the extent of open defecation in Open defecation within a community harms the physical a community, sanitation policies would best prioritize and cognitive development of children, even children living in collective community-wide behavior change to stop households that use toilets themselves. Frequently digesting open defecation; incentives, policies, and targets that feces due to poor sanitation can cause diarrhea, malnutrition, encourage collective behavior change are needed. and stunted growth-and thus impact negatively on a child’s cognitive development (Box 1). Experiencing these health haz- • Poor households with severe cash constraints are ards at young ages can ultimately limit one’s earning potential best supported through programs that focus on later in life. collective outcomes, complemented by targeted household support. -

Sustainable Environmental Protection Using Modified Pit-Latrines

Sustainable Environmental Protection Using Modified Pit-Latrines Esnati James Chaggu Promotor: Prof. dr.ir. G. Lettinga Hoogleraar in de anaërobe zuiveringstechnologie en hergebruik van afvalstoffen Co-promotoren: Dr. W. T. M. Sanders Post-doc onderzoeker bij de sectie Milieutechnologie, Wageningen Universiteit, Nederland Prof. A. Mashauri Dar-es-Salaam Universiteit, Tanzania Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Prof. G. Spaargaren Wageningen Universiteit Prof. dr. H. J. Gijzen UNESCO-IHE, Delft, Nederland Dr. G. J. Medema KIWA Water Research, Nieuwegein, Nederland Prof. Dr. H. Folmer Wageningen Universiteit Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoekschool Wimek Sustainable Environmental Protection Using Modified Pit-Latrines Esnati James Chaggu Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. Ir. L. Speelman, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 23 maart 2003 des namiddags te half twee in de aula CIP-DATA KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG. Chaggu, E. J. Sustainable Environmental Protection Using Modified Pit-Latrines ISBN: 90-5808-989-4 Subject headings: excreta disposal/blackwater/nightsoil/anaerobic digestion/improved pit latrines Abstract - Chaggu, E. J. (2004). Sustainable Environmental Protection Using Modified Pit-Latrines. Ph.D Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Pit-latrines are on-site excreta disposal facilities widely used as anaerobic accumulation system for stabilizing human wastes like excreta, both in rural and urban settlements of developing countries. Flooding of pit-latrines is often a common phenomenon, especially in situations of high water table (HWT) conditions and during the rainy season, causing a health jeopardy to residents. The pits are not water-tight, the (ground)water can freely flow in and out of the pit, especially in HWT areas. -

Chapter 9: Outline Notes “Ancient India” Lesson 9.1 – Early Civilizations

Name: ______________________________________ Date: _____________ Period: __________ #: _____ Chapter 9: Outline Notes “Ancient India” Lesson 9.1 – Early Civilizations The Geography of India: India and several other countries make up the _______________________ of India. o A subcontinent is a large _______________ that is smaller than a continent. The Indian subcontinent is part of the ____________. 1. Mountains, Plains, and Rivers: a. To the north, India is separated from the rest of Asia by rugged mountain system. One of these mountains systems in the __________________ that has the tallest mountain in the world ____________ ______________. b. Wide fertile plains lie at the foot of India’s extensive mountain ranges. The plains owe their rich soil to the three great rivers that flow through the region. These are the _________, Ganges, and ________________________ rivers. c. The landforms in central and southern India are much different from the landforms in the north. d. Along the west and east coasts are lush ______________ ________. Further inland there are eroded mountains that left areas of rugged _________. e. Between the mountains is a dry highland known as the ____________________ ______________. f. Seasonal winds called ____________________ have a large influence on India’s climate. The summer rains bring farmers ___________ that they need for their ____________. People _________ the arrival of the monsoon rains. However, they sometimes cause ______________ that destroy crops and can even kill _______________ and ________________. If the rain comes too late, there may be a long dry period called a _________________. The Indus Valley Civilization: India’s first civilization began in the valley around the _____________ River. -

HEALTH ASPECTS of DRY SANITATION with WASTE REUSE Anne Peasey

HEALTH ASPECTS OF DRY SANITATION WITH WASTE REUSE Anne Peasey Task No. 324 WELL STUDIES IN WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse Anne Peasey WELL Water and Environmental Health at London and Loughborough Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse ii London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Keppel Street London WC1E 7HT © LSHTM/WEDC Peasey, A. (2000) Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse WELL Designed and Produced at LSHTM Health Aspects of Dry Sanitation with Waste Reuse EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND Dry sanitation is defined in this report as the on-site disposal of human urine and faeces without the use of water as a carrier. This definition includes many of the most popular options for low- cost sanitation including pit latrines, Ventilated Improved Pits, SanPlats, etc. There has always been an interest in the reuse of human waste as a fertiliser, and there has been much recent work on the development of composting and other processes to permit human waste reuse. This report examines the practice of dry sanitation with reuse in Mexico, with a particular focus on health issues and the lessons to be learned from case studies and experience. DRY SANITATION WITH REUSE There are two distinct technical approaches to dry sanitation with reuse; · Dehydration. Urine and faeces are managed separately. The deposited faecal matter may be dried by the addition of lime, ash, or earth, and the contents are simply isolated from human contact for a specified period of time to reduce the presence of pathogens. · Decomposition (composting) In this process, bacteria, worms, or other organisms are used to break organic matter down to produce compost. -

DOCTORAL THESIS Carrying Queerness Queerness, Performance

DOCTORAL THESIS Carrying Queerness Queerness, Performance and the Archive Hunt, Raymond Justin Award date: 2013 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Carrying Queerness: Queerness, Performance and the Archive by Raymond Justin Hunt, BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Drama, Theatre and Performance University of Roehampton 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation responds to the archival turn in critical theory by examining a relation between queerness, performance and the archive. In it I explore institutional archives and the metaphors of the archive as it operates in the academy, while focusing particularly on the way in which queerness may come to be archived. Throughout I use the analytic of performance. This work builds on and extends from crucial work in Queer studies, Performance Studies and Archival Studies. -

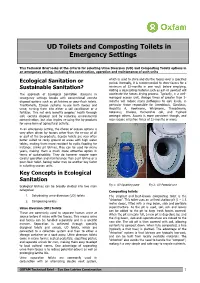

UD & Composting Toilets (Ecosan)

UD Toilets and Composting Toilets in Emergency Settings This Technical Brief looks at the criteria for selecting Urine Diversion (UD) and Composting Toilets options in an emergency setting, including the construction, operation and maintenance of such units which is used to store and dry the faeces over a specified Ecological Sanitation or period. Normally, it is recommended to store faeces for a Sustainable Sanitation? minimum of 12-months in one vault before emptying. Adding a desiccating material such as ash or sawdust will The approach of Ecological Sanitation (Ecosan) in accelerate the faeces drying process. Typically, in a well- emergency settings breaks with conventional excreta managed ecosan unit, storage times of greater than 3- disposal options such as pit latrines or pour-flush toilets. months will reduce many pathogens to safe levels, in Traditionally, Ecosan systems re-use both faeces and particular those responsible for Ameobiasis, Giardiasis, urine, turning them into either a soil conditioner or a Hepatitis A, Hookworm, Whipworm, Threadworm, fertilizer. This not only benefits peoples’ health through Rotavirus, Cholera, Escherichia coli, and Typhoid safe excreta disposal and by reducing environmental amongst others. Ascaris is more persistent though, and contamination, but also implies re-using the by-products may require retention times of 12-months or more. for some form of agricultural activity. In an emergency setting, the choice of ecosan options is very often driven by factors other than the re-use of all or part of the by-products. Ecosan toilets are very often better suited to rocky ground or areas with high water tables, making them more resistant to cyclic flooding for instance. -

Ano-Vesical Reflex: Role in Inducing Micturition in Paraplegic Patients

Paraplegia 32 (1994) 104-107 © 1994 International Medical Society of Paraplegia Ano-vesical reflex: role in inducing micturition in paraplegic patients A Shafik MD Professor and Chairman, Department of Surgery and Research, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt. The reflex relationship between the anal canal and the urinary bladder was investigated in 14 normal volunteers and in seven patients with spinal cord injury of more than 2 years duration. The latter induced urination by dilating the anal canal with the finger. The vesical pressure was measured by a balloon-tipped catheter introduced into the urinary bladder which was filled with 100 ml saline. The anal canal was inflated with a balloon catheter filled with 2 ml air; inflation was increased in increments of 2 ml up to 10 ml. The vesical pressure in response to both slow and rapid anal distension was recorded. The external and internal anal sphincters were blocked separately and the test was repeated. Rapid anal inflation elevated the vesical pressure. The greater the anal inflation, the higher the vesical pressure. Slow anal distension induced insignificant vesical pressure changes (p > 0.05). Rapid anal distension with internal sphincter block induced insignificant vesical pressure changes (p > 0.05) while the vesical pressure showed a significant increase with external sphincter block. In paraplegic subjects, the vesical pressure increased on rapid anal distension with 6 ml air but did not further increase with greater distension. Vesical pressure increase was recorded after external sphincter block but there was an insignificant change after internal sphincter paralysis. The aforementioned results were reproducible.