161 A.D. Renting & J.T.C. Renting-Cuijpers, Catalogus Van De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College and Research Libraries

Destruction of Knowledge: A Study of Journal Mutilation at a Large University Library Constantia Constantinou Book and journal mutilation is a problem for libraries. The rising cost of replacing mutilated books and journals and the availability of out-of-print materials concerns many librarians. This paper examines one type of mutilation-the removal of pages from journal titles at the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library of New York University. The study reviews the related lit erature; it discusses the methodology of the descriptive study on journal mutilation at Bobst Library; it analyzes and interprets the results of the study, makes suggestions that could help reduce the problem, and pro poses other topics for additional research. ot long ago, an e-mail mes new publications, the cost of replac sage circulated among library ing older, heavily used material is a collection staff which dis real concern. As well, several of the cussed the increasing prob items are no longer in print and we lem of book and journal mutilation. The are unable to replace them. I message outlining these issues read as fol would appreciate hearing any ideas lows: for preventing, minimizing or cop ing.with the situation.1 This past term our library staff no ticed an increase in the number of Review of Related Literature books and journal issues that are Libraries realize that book and journal being damaged, e.g., pictures ra mutilation is a growing problem that sim zor[ed] or torn out [and] entire con ply does not go away. It is costly and dis tents removed with only the covers ruptive for both libraries and library us left on the shelves or in nearby gar ers. -

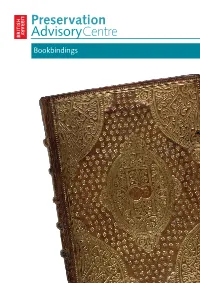

Understanding and Caring for Bookbindings

Preservation AdvisoryCentre Bookbindings The Preservation Advisory Centre has been awarded the CILIP Seal of Recognition based on an independent review of the content of its training courses and its engagement with the CILIP Body of Professional Knowledge. The production of this booklet has been supported by Collections Link www.collectionslink.org.uk The Preservation Advisory Centre is supported by: Authors David Pearson, John Mumford, Alison Walker David Pearson is Director of Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London ISBN 0 7123 4982 0 Design The British Library Design Office Cover The Booke of Common Prayer with the Psalter (bound with Bible and psalmes), London 1626. Upper cover, brown calf, tooled in gold. First published November 2006 Revised November 2010 Understanding and caring for bookbindings Developing expertise in recognising and dating bindings is largely a matter of experience, of looking and handling, and many people with responsibility for historic book collections will readily admit that bindings is an area in which they feel they would like to have more detailed knowledge. The key message is that all bindings, however unspectacular they may look, are potentially of interest to historians of the book and cultural historians. Vast quantities of evidence about the ways in which books were sold and circulated in the past has been lost or compromised through the entirely well-intentioned repair work of previous generations, and some of the cheapest and simplest kinds of early bookbindings are now the hardest to find. Provincial collections may contain the work of local bookbinders which will survive nowhere else. Bookbindings are worth preserving not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their value as an intrinsic part of our documentary cultural heritage. -

Puritan Bride Ebook

PURITAN BRIDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne O'Brien | 464 pages | 19 Aug 2011 | Mira Books | 9780778304036 | English | Don Mills, Canada Puritan Bride PDF Book The Puritans, if you remember, broke away from the Church of England. Inspired by the true love story of John and Elizabeth Bunyan Gummies But the marriage ways of Massachusetts in their totality were a unique amalgam of Puritan ideas and East Anglian practices. Once the marriage occurred, women, on average, gave birth to between six and eight children Stuart. Trivia About Puritan Bride. Not Bad Not too bad a read, a bit repetitive in places with regards to the emotions of the main characters but as a whole the book is an easy, pleasant read and it helped pass some of the time during the Coronovirus lock down. Roe, Sue. It is a historical romance with a ghost thrown in. C11 Shop By Category. Unflavored 3. From the start, things were different in the Puritan colonies. In the other, that the book was the most disappointing from the author since there were high expectations due to accolades for her other books. The higher classes generally did not favor the education of any peasants to prevent them from aspiring above their station. Offers for Purtian products. We use it to diagnose problems with the site, and understand how people use our website. On the wedding night, the bride dressed in a special gown, and was put to bed by friends who accompanied the couple into the chamber, and then gave them a joyous charivari with much banging and bell-ringing outside the chamber. -

The Shared Cataloging System of the Ohio College Library Center

THE SHARED CATALOGING SYSTEM OF THE OHIO COLLEGE LIBRARY CENTER Frederick G. KILGOUR, Philip L. LONG, Alan L. LANDGRAF, and John A. WYCKOFF: Ohio College Library Center, Columbus, Ohio Development and implementation of an off-line catalog card production system and an on-line shared cataloging system are described. In off-line production, average cost per card for 529,893 catalog cards in finished form and alphabetized for filing was 6.57 (·. An account is given of system design and equipment selection for the on-line system. File organization and pro grams are described, and the on-line cataloging system is discussed. The system is easy to use, efficient, 1'eliable, and cost beneficial. The Ohio College Library Center ( OCLC) is a not-for-profit corporation chartered by the State of Ohio on 6 July 1967. Ohio colleges and universi ties may become members of the center; forty-nine institutions are partici pating in 1971/ 72. The center may also work with other regional centers that may "become a part of any national electronic network for bibliographic communication." The objectives of OCLC are to increase the availability to individual students and faculty of resources in Ohio's academic libraries, and at the same time to decrease the rate of rise of library costs per student. The OCLC system complies with national and international standards and has been designed to operate as a node in a future national network as well as to attain the more immediate target of providing computer support to Ohio academic libraries. The system is based on a central computer with a large, random access, secondary memory, and cathode ray tube terminals which are connected to the central computer by a network of telephone circuits. -

Wells Cathedral Chained Library Catalogue by Author - A

CATALOGUE Wells Cathedral has added the catalogue of its approximately 4,000 books in the Chained Library to its website for illustrative purposes in response to enquiries about the scope of the collection. The part-time nature of the library staffing is such that we can respond to genuine enquiries from scholars who can verify their research qualifications and needs, but more general enquiries may wait some time for a response. The books of the Chained Library can be viewed during our special Library Tours. These can be booked via [email protected] or call 01749 674483 and ask to speak to Visits. Research enquiries from scholars should be addressed to the Cathedral Librarian, Kevin Spears [email protected] EXCEL NOTES Column headings A = Author B = Title C= Date of publication D = Place of Publication E = Donor F = Bibliographical reference KEY TO BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES STC = POLLARD, A W and REDGRAVE, G R Short-Title catalogue of books printed in England, Scotland, Ireland, etc 1475-1640 London, 1986 WA-WZ = WING, D. Short-Title catalogue of books printed in England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, etc 1641-1700 New York, 1994 CLCA-CLCZ = Cathedral Libraries Catalogue of books printed before 1701 in the Anglican Cathedrals of England and Wales London, 1984 Ker = KER, N R and PIPER, A J Medieval manuscripts in British Libraries Oxford, 1992 Wells Cathedral Chained Library Catalogue by Author - A ABCDEF BIBLIO- DATE OF PLACE OF GRAPHICAL 1 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLICATION PUBLICATION DONOR REFERENCE 2 ABENDANA,Isaac Discourses -

Book Club Guide

Book Club Guide Inlcuding a letter from author Charlie Lovett, a Q&A with Charlie Lovett, suggested questions for discussion, and additional resources for your book club meeting or personal reflection. www.charlielovett.com @CharlieLovett42 @charlielovett.author ear Readers, On January 23, 1980 I had my first experience of a British medieval cathedral when I went with a school group to Ely. I was seventeen years old and I have loved English cathedrals ever since. In 2000, I made a six week pilgrimage tracing the roots of British Christianity from Iona, Scotland to Canterbury. Along the way I visited sixteen medieval cathedrals, often spending the entire day exploring the precincts, taking tours, and attending services. Often, somewhere within the cathedral complex, I would come across a wooden door, firm- ly shut, bearing a small sign that read “Library: Closed to the Public.” Years later, when I sat down to begin my third novel, I considered the two I had already written and noticed a common thread (other than rare books). The Bookman’s Tale was partially set in a university rare book library. First Impressions included two English country house libraries in two different centuries. What other kinds of libraries are there, I thought? Then I remembered those closed doors at all those cathedrals. I wanted to discover what was behind those doors—so I wrote The Lost Book of the Grail. Having found the setting for the book, I needed to populate it with characters. What sort of person, I thought, would want to spend all his time in a cathedral library? If you want to know how I answered that question, look no further than Arthur Prescott. -

Harrod's Librarians' Glossary and Reference Book

TENTH EDITION HARROD’S LIBRARIANS’ GLOSSARY AND REFERENCE BOOK A Directory of Over 10,200 Terms, Organizations, Projects and Acronyms in the Areas of Information Management, Library Science, Publishing and Archive Management Compiled by Ray Prytherch HARROD’S LIBRARIANS’ GLOSSARY AND REFERENCE BOOK A Directory of Over 10,200 Terms, Organizations, Projects and Acronyms in the Areas of Information Management, Library Science, Publishing and Archive Management This page has been left blank intentionally HARROD’S LIBRARIANS’ GLOSSARY AND REFERENCE BOOK A Directory of Over 10,200 Terms, Organizations, Projects and Acronyms in the Areas of Information Management, Library Science, Publishing and Archive Management Tenth Edition Compiled by RAY PRYTHERCH © Ray Prytherch 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. The author name has asserted his/her moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Gower House Suite 420 Croft Road 101 Cherry Street Aldershot Burlington, VT 05401-4405 Hampshire GU11 3HR USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Harrod’s librarians’ glossary and reference book: a directory of over 10,200 terms, organizations, projects and acronyms in the areas of information management, library science, publishing and archive management. - 10th ed 1. Library science - Dictionaries 2. Information science - Dictionaries 3. Publishers and publishing - Dictionaries 4. Book industries and trade - Dictionaries 5.Archives - Administration - Dictionaries I.Prytherch, Raymond John II.Harrod, Leonard Montague III.Librarians’ glossary and reference book 020.3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prytherch, Raymond John. -

Sandra Hindman Ariane Bergeron-Foote

SANDRA HINDMAN ARIANE BERGERON-FOOTE LES ENLUMINURES LE LOUVRE DES ANTIQUAIRES 2 PLACE DU PALAIS-ROYAL - 75001 PARIS TEL (33) (0)1 42 60 15 58 - FAX (33) (0)1 40 15 00 25 [email protected] LES ENLUMINURES LTD. 2970 NORTH LAKE SHORE DRIVE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60657 TEL: (773) 929 5986 - FAX: (773) 528 3976 [email protected] BINDING catalogue intérieur SIMONE:2010 12/11/10 17.24 Pagina 1 Binding and the Archeology of the Medieval and Renaissance Book sandra hindman ariane bergeron-foote BINDING catalogue intérieur SIMONE:2010 12/11/10 17.24 Pagina 2 LES ENLUMINURES LTD . 2970 NORTH LAKE SHORE DRIVE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60657 TEL: (773) 929 5986 FAX: (773) 528 3976 [email protected] LES ENLUMINURES LE LOUVRE DES ANTIQUAIRES 2 PLACE DU PALAIS-ROYAL 75001 PARIS TEL (33) (0)1 42 60 15 58 FAX (33) (0)1 40 15 00 25 [email protected] WWW.LESENLUMINURES.COM WWW.TEXTMANUSCRIPTS.COM WWW.MEDIEVALBOOKSOFHOURS.COM FULL DESCRIPTIONS AVAILABLE ON WWW.TEXTMANUSCRIPTS.COM AND WWW.MEDIEVALBOOKSOFHOURS.COM © SANDRA HINDMAN AND ARIANE BERGERON-FOOTE ISBN 0-9679663-9-6 BINDING catalogue intérieur SIMONE:2010 12/11/10 17.24 Pagina 3 Binding and the Archeology of the Medieval and Renaissance Book sandra hindman ariane bergeron-foote BINDING catalogue intérieur SIMONE:2010 12/11/10 17.24 Pagina 4 BINDING catalogue intérieur SIMONE:2010 12/11/10 17.24 Pagina 5 INTRODUCTION The publication of Binding and the Archeology of the Medieval and the Renaissance Book celebrates the 10-year anniversary of www.textmanuscripts.com, the website of Les Enluminures devoted exclusively to manuscripts interesting for their texts. -

Bookshelf by Lydia Pyne

“The Object Lessons series achieves something very close to magic: the books take ordinary— even banal—objects and animate them with a rich history of invention, political struggle, science, and popular mythology. Filled with fascinating details and conveyed in sharp, accessible prose, the books make the everyday world come to life. Be warned: once you’ve read a few of these, you’ll start walking around your house, picking up random objects, and musing aloud: ‘I wonder what the story is behind this thing?’ Steven Johnson, author of Where Good Ideas Come From and How We Got to Now “In 1957 the French critic and semiotician Roland Barthes published Mythologies, a groundbreaking series of essays in which he analysed the popular culture of his day, from laundry detergent to the face of Greta Garbo, professional wrestling to the Citroën DS. This series of short books, Object Lessons, continues the tradition. Melissa Harrison, Financial Times PRAISE FOR HOTEL BY JOANNA WALSH: “A slim, sharp meditation on hotels and desire. ... Walsh invokes everyone from Freud to Forster to Mae West to the Marx Brothers. She’s funny throughout, even as she documents the dissolution of her marriage and the peculiar brand of alienation on offer in lavish places. Dan Piepenbring, The Paris Review “Evocative ... Walsh’s strange, probing book is all the more affecting for eschewing easy resolution. Publishers Weekly “Walsh’s writing has intellectual rigour and bags of formal bravery ... Hotel is a boldly intellectual work that repays careful reading. Its semiotic wordplay, circling prose and experimental form may prove a refined taste, but in its deft delineation of a complex modern phenomenon—and, perhaps, a modern malaise—it’s a great success. -

Locating Librarianship's Identity in Its Historical Roots Of

http://conference.ifla.org/ifla78 Date submitted: 27 June 2012 Locating Librarianship’s Identity in its Historical Roots of Professional Philosophies: Towards a Radical New Identity for Librarians of Today (and Tomorrow) Sara Wingate Gray Department of Information Studies University College London London, United Kingdom Meeting: 95 — Strategies for library associations: include new professionals now! — Management of Library Associations with the New Professionals Special Interest Group Abstract: ‘Librarian identity’ is a contested arena, seemingly caught up in a values-war between traditional principles of ‘citizenship’ and late twentieth century’s shift to a democracy of consumerists. New professionals may be wary of associating with established systems of their own professional hierarchies when such Associations may be perceived as not having paid enough attention to how this shift in values has been effected, yet this is the key question to address: how has this shift towards “information management/consumption”; the library member now as “customer”; and new models of library provision by private or social enterprises, impacted on the profession’s identity as a whole? What does it means to call yourself a Librarian in the 21st century? This paper will trace the roots of the philosophy of Librarianship, in its changing shapes, to establish how professional identities are formed, ranging from Edwards and Dewey’s originating ‘librarian’ as book keeper/cataloguer or library ‘economiser’; through to Otlet and Shera’s ‘Documentationalist’; Ranganathan’s librarian ‘helper’; and present day incarnations such as Lankes’s librarian as ‘community knowledge creation facilitator’. Incorporating historical analysis of the roots of librarianship’s philosophies, this paper develops a thesis relating to how modern day librarian professionals, practicing in non-traditional areas and ways, may be helpful in suggesting a route out of the LIS echo-chamber of identity crisis, alongside the evidence of librarianship’s historical trail. -

Introduction to Library and Information Science

Introduction to Library and Information Science en.wikibooks.org September 1, 2015 On the 28th of April 2012 the contents of the English as well as German Wikibooks and Wikipedia projects were licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license. A URI to this license is given in the list of figures on page 81. If this document is a derived work from the contents of one of these projects and the content was still licensed by the project under this license at the time of derivation this document has to be licensed under the same, a similar or a compatible license, as stated in section 4b of the license. The list of contributors is included in chapter Contributors on page 79. The licenses GPL, LGPL and GFDL are included in chapter Licenses on page 85, since this book and/or parts of it may or may not be licensed under one or more of these licenses, and thus require inclusion of these licenses. The licenses of the figures are given in the list of figures on page 81. This PDF was generated by the LATEX typesetting software. The LATEX source code is included as an attachment (source.7z.txt) in this PDF file. To extract the source from the PDF file, you can use the pdfdetach tool including in the poppler suite, or the http://www. pdflabs.com/tools/pdftk-the-pdf-toolkit/ utility. Some PDF viewers may also let you save the attachment to a file. After extracting it from the PDF file you have to rename it to source.7z. -

Revisiting Cataloging in Medieval Libraries

Cataloging and Classification Quarterly, 1998, vol. 26, no. 3, p.21-30. ISSN: (Print: 0163-9374) (Electronic: 1544-4554) DOI: 10.1300/J104v26n03_03 http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/titles/01639374.asp http://www.informaworld.com/10.1300/J104v26n03_03 © 1998 The Haworth Press Hidden Wisdom and Unseen Treasure: Revisiting Cataloging in Medieval Libraries Beth M. Russell Beth M. Russell, MA, MLIS, is Original Cataloging Librarian, Cushing Memorial Library, Texas A&M University. ABSTRACT. Scholars working in the fields of medieval history and cultural history have recognized that understanding the cataloging and accessioning of books is central to understanding the transmission of ideas. This view should come as no surprise to catalogers themselves, who daily struggle with the problem of providing intellectual, and sometimes physical, access to texts and information. Unfortunately, general histories of libraries and even the library literature seem content to sketch out a chronological development of cataloging in line with the nineteenth and twentieth century view of library development, from a simple list to complex intellectual systems. In truth, however, those individuals responsible for cataloging books in medieval libraries faced many of the same challenges as catalogers today: how to organize information, how to serve local needs, and how to provide access to individual works within larger bibliographic.formats. This article will summarize recent scholarship in the history of the book that relates to library cataloging, as well as providing