Revisiting Cataloging in Medieval Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations Jean-Pierre V

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Faculty and Staff choS larship and Research Purdue Libraries 2016 To Honor Our Past: Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations Jean-Pierre V. M. Hérubel Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Hérubel, Jean-Pierre V. M., "To Honor Our Past: Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations" (2016). Libraries Faculty and Staff Scholarship and Research. Paper 140. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs/140 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. To Honor Our Past: Historical Research, Library History and the Historiographical Imperative: Conceptual Reflections and Exploratory Observations Jean-Pierre V. M. Hérubel HSSE, University Libraries, Purdue University Abstract: This exploratory discussion considers history of libraries, in its broadest context; moreover, it frames the entire enterprise of pursuing history as it relates to LIS in the context of doing history and of doing history vis-à-vis LIS. Is it valuable intellectually for LIS professionals to consider their own history, writing historically oriented research, and what is the nature of this research within the professionalization of LIS itself as both practice and discipline? Necessarily conceptual and offering theoretical insight, this discussion perforce tenders the idea that historiographical innovations and other disciplinary approaches and perspectives can invigorate library history beyond its current condition. -

On the Value of Archival History in the United States Author(S): Richard J

University of Texas Press On the Value of Archival History in the United States Author(s): Richard J. Cox Source: Libraries & Culture, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Spring, 1988), pp. 135-151 Published by: University of Texas Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25542039 Accessed: 14/12/2010 11:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=texas. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Texas Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Libraries & Culture. http://www.jstor.org On the Value of Archival History in the United States Richard J, Cox Although there is increasing interest in American archival history, there no an has been precise definition of its value. -

College and Research Libraries

Destruction of Knowledge: A Study of Journal Mutilation at a Large University Library Constantia Constantinou Book and journal mutilation is a problem for libraries. The rising cost of replacing mutilated books and journals and the availability of out-of-print materials concerns many librarians. This paper examines one type of mutilation-the removal of pages from journal titles at the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library of New York University. The study reviews the related lit erature; it discusses the methodology of the descriptive study on journal mutilation at Bobst Library; it analyzes and interprets the results of the study, makes suggestions that could help reduce the problem, and pro poses other topics for additional research. ot long ago, an e-mail mes new publications, the cost of replac sage circulated among library ing older, heavily used material is a collection staff which dis real concern. As well, several of the cussed the increasing prob items are no longer in print and we lem of book and journal mutilation. The are unable to replace them. I message outlining these issues read as fol would appreciate hearing any ideas lows: for preventing, minimizing or cop ing.with the situation.1 This past term our library staff no ticed an increase in the number of Review of Related Literature books and journal issues that are Libraries realize that book and journal being damaged, e.g., pictures ra mutilation is a growing problem that sim zor[ed] or torn out [and] entire con ply does not go away. It is costly and dis tents removed with only the covers ruptive for both libraries and library us left on the shelves or in nearby gar ers. -

The Modern History of the Library Movement and Reading Campaign in Korea

Date : 27/06/2006 The modern history of the library movement and reading campaign in Korea Yong-jae Lee Assistant Professor Department of Library, Archive and Information Studies Pusan National University, 30 Janjeon-dong, Geumjeong-gu, Pusan, 609-735 Republic of Korea And Jae-soon Jo, Librarian The Korean National University of Arts Library San 1-5, Seokgwang-dong, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, 136-716 Republic of Korea Meeting: 119 Library History Simultaneous Interpretation: No WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 72ND IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 20-24 August 2006, Seoul, Korea http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla72/index.htm ABSTRACT This paper explores the history of library movement and reading campaign in Korea since 1900. Korean people tried in many ways to establish their own libraries in 20th century. Many library thinkers, intellectuals, and librarians have struggled to build 1 modern libraries in communities or nationwide. Although Korea has a brilliant history of record and print, it has been so hard to establish libraries for the Korean people during last century. The Korean libraries have endured hardships such as Japanese colonialism, Korean War, and military dictatorship. This paper examines the Korean people’s efforts to establish libraries, and it looks into the history of library movement in Korea. And also this paper introduces the recent reading campaigns such as ‘Bookstart’, ‘One Book One City’. With historical lessons suggested in this paper, people may have some insight to make and develop libraries in Korea. 2 1. Introduction Korean public libraries in the 20th Century grew by undergoing history of formidable obstacles. -

Republic of Palau

REPUBLIC OF PALAU Palau Public Library Five-Year State Plan 2020-2022 For submission to the Institute of Museum and Library Services Submitted by: Palau Public Library Ministry of Education Republic of Palau 96940 April 22, 2019 Palau Five-Year Plan 1 2020-2022 MISSION The Palau Public Library is to serve as a gateway for lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources and to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate and resourceful in the Palauan society and the world. PALAU PUBLIC LIBRARY BACKGROUND The Palau Public Library (PPL), was established in 1964, comes under the Ministry of Education. It is the only public library in the Republic of Palau, with collections totaling more than 20,000. The library has three full-time staff, the Librarian, the Library Assistant, and the Library Aide/Bookmobile Operator. The mission of the PPL is to serve as a gateway to lifelong learning and easy access to a wide range of information resources to ensure the residents of Palau will be successful, literate, and resourceful in the Palauan society and world. The PPL strives to provide access to materials, information resources, and services for community residents of all ages for professional and personal development, enjoyment, and educational needs. In addition, the library provides access to EBSCOHost databases and links to open access sources of scholarly information. It seeks to promote easy access to a wide range of resources and information and to create activities and programs for all residents of Palau. The PPL serves as the library for Palau High School, the only public high school in the Republic of Palau. -

The Literature of American Library History, 2003–2005 Edward A

Collections and Technical Services Publications and Collections and Technical Services Papers 2008 The Literature of American Library History, 2003–2005 Edward A. Goedeken Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/libcat_pubs Part of the Library and Information Science Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ libcat_pubs/12. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Collections and Technical Services at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collections and Technical Services Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Literature of American Library History, 2003–2005 Abstract A number of years have elapsed since publication of the last essay of this sort, so this one will cover three years of historical writings on American librarianship, 2003–5, instead of the usual two. We will have to see whether this new method becomes the norm or will ultimately be considered an aberration from the traditional approach. I do know that several years ago Donald G. Davis, Jr., and Michael Harris covered three years (1971–73) in their essay, and we all survived the experience. In preparing this essay I discovered that when another year of coverage is added the volume of writings to cover also grows impressively. A conservative estimate places the number of books and articles published in the years under review at more than two hundred items. -

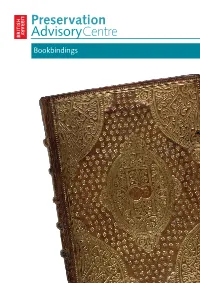

Understanding and Caring for Bookbindings

Preservation AdvisoryCentre Bookbindings The Preservation Advisory Centre has been awarded the CILIP Seal of Recognition based on an independent review of the content of its training courses and its engagement with the CILIP Body of Professional Knowledge. The production of this booklet has been supported by Collections Link www.collectionslink.org.uk The Preservation Advisory Centre is supported by: Authors David Pearson, John Mumford, Alison Walker David Pearson is Director of Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London ISBN 0 7123 4982 0 Design The British Library Design Office Cover The Booke of Common Prayer with the Psalter (bound with Bible and psalmes), London 1626. Upper cover, brown calf, tooled in gold. First published November 2006 Revised November 2010 Understanding and caring for bookbindings Developing expertise in recognising and dating bindings is largely a matter of experience, of looking and handling, and many people with responsibility for historic book collections will readily admit that bindings is an area in which they feel they would like to have more detailed knowledge. The key message is that all bindings, however unspectacular they may look, are potentially of interest to historians of the book and cultural historians. Vast quantities of evidence about the ways in which books were sold and circulated in the past has been lost or compromised through the entirely well-intentioned repair work of previous generations, and some of the cheapest and simplest kinds of early bookbindings are now the hardest to find. Provincial collections may contain the work of local bookbinders which will survive nowhere else. Bookbindings are worth preserving not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their value as an intrinsic part of our documentary cultural heritage. -

The Science Library Catalog: a Springboard for Information Literacy

The Science Library Catalog: A Springboard for Information Literacy SLMQ Volume 24, Number 2, Winter 1996 Virginia A. Walter, Christine L. Borgman, and Sandra G. Hirsh, Department of Library and Information Science, Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, University of California, Los Angeles. The world of electronic information is increasingly important, and opening that world to children is a critical part of the library media specialist’s job. That task would be much easier, of course, if electronic information resources were more “child-friendly.” A number of researchers in our field are tackling design issues related to children’s use of these resources, and the creators of the Science Library Catalog (SLC) are pioneers in this effort. Led by Christine Borgman, this research team has been designing successive versions of the SLC and using them as a platform for longitudinal research for almost a decade. In this column, the team summarizes its experiences to date. The column outlines the cognitive theories that have informed the SLC’s ongoing design; describes the catalog itself; explains the continuing research effort based on the SLC; and discusses the research results-emphasizing the findings that are most relevant to school library media specialists as they seek to develop children’s information skills. References to others’ work-including Paul Solomon’s fall 1994 “Current Research” column-suggest the expanding research base that is beginning to establish design criteria for electronic information resources for children. -

INTRODUCTION Traditionally, the Bookmobile Has Played An

INTRODUCTION tomer base; public libraries are constantly striving to gain new patronage. Ideally we would like all those Traditionally, the bookmobile has played an taxpayers who financially support the library to use the important role in meeting the needs of the reading library and benefit from its services. Reaching out to d1e public and in providing information to a broad segment far corners of the library district is a priority goal for all of society. But in the past few years, bookmobiles have public libraries. Of course libraries approach outreach fallen on hard times, and their demise has long been in many different ways depending on the size and predicted. They have fallen victim to such things as the population of the library district. The traditional library gas crisis, construction of branch libraries, and automa outreach mechanisms provides books and other tion. materials to those who are unlikely or unable to reach Bookmobiles, or traveling libraries, are an exten the physical library. According to recent studies, sion of the services offered by the conventional library. bookmobiles and branches have bee n d1e two main Usually, a bookmobile is operated by a public library service outlets used nationwide by public libraries. Of system and it travels on a scheduled, repetitive route to the 8,981 public libraries in the United States in 1995, schools, small towns, crossroads, and shopping centers. I466 or 16% had branches and 819 or 9% had bookmo Its driver is often also the librarian. The inventory of biles. The number of libraries, branches, and bookmo materials it carries varies, as the librarian tries to meet biles that each state has varies greatly. -

Medical Library Association MLA '18 Poster Abstracts

Medical Library Association MLA ’18 Poster Abstracts Abstracts for the poster sessions are reviewed by members of the Medical Library Association National Program Committee (NPC), and designated NPC members make the final selection of posters to be presented at the annual meeting. 1 Poster Number: 1 Time: Tuesday, May 22, 1:00 PM – 1:55 PM Bringing Each Other into the FOLD: Shared Experiences in Start-up Osteopathic Medical School Libraries Darell Schmick, AHIP, Director of Library Services, University of the Incarnate Word, School of Osteopathic Medicine Library, San Antonio, TX; Elizabeth Wright, Director of Library Services, Arkansas College of Osteopathic Medicine, Arkansas Colleges of Health Education, Library, Fort Smith, AR; Erin Palazzolo, Library Director and Professor of Medical Informatics, Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine at New Mexico State University, BCOM Library, Las Cruces, NM; Norice Lee, Assoc. Library Director & Assoc. Prof. / Medical Informatics, Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine Health Sciences Library, Las Cruces, NM; Molly Montgomery, Director of Library Services, Proposed Idaho College of Osteopathic Medicine, Library, Meridian, ID; Anna Yang, AHIP, Health Sciences Librarian, California Health Sciences University, Library, Clovis, CA Objectives: To establish a communication channel for founding library administrators of new medical schools. Methods: Library directors in founding osteopathic medical schools are faced with a unique set of challenges in this role. Depending on the establishing medical school’s structure, these can be librarians in a solo capacity. Librarians in this role share experiences and best practices over a monthly meeting for their inaugural and second academic school years, respectively. Results: Meetings enjoyed robust discussion and comparison of resources. -

Diane Cory's Early History of Berkeley Public

THE HISTORY AND ORIGINS OF THE BERKELEY PUBLIC LIBRARY Librarianship 225c May 25, 1962 Diane Cory INTRODUCTION This paper is limited in scope to the early years of the library in an attempt to have a complete and exhaustive account of this period. I would like to take this opportunity to say a word about my sources and their arrangement in the bibliography. For the most important part of the paper, I. e. the founding and early history of the library, relatively few sources were used. These included the Minutes of the Holmes Library Association and those of the Library Trustees, newspapers of the period, particularly 1894 for which year there were no minutes, and the letters, Constitution and Dedication program found in the Librarian’s Office. In some cases, where it seemed of value to know where these early sources are located, I have done so. Those things found at the Berkeley Public Library are not filed in any particular order. For the early history of Berkeley, there were several valuable books, in particular the ones by Mary Ruth Houston, J. Bowman and S. D. Waterman. The latter I have included as a primary source assuming that this author is the same Mr. Waterman so active on the Library Board. Although Mr. Ferrier’s book is referred to a number of times in footnotes, I tried to use it primarily for incidental information which was not readily available in other sources and which broadened the picture since it was not documented in any way. Finally, I have included a number of works under (d) which I consulted but did not use either because they had no information at all on the subject or very little, and which was easily duplicated in other sources. -

THE LIBRARY Coordinator of Library Services 276.964.7266 [email protected]

CONNECTIONS Dr. Teresa A. Yearout, Librarian THE LIBRARY Coordinator of Library Services 276.964.7266 www.sw.edu/library [email protected] Diane Phillips, Librarian IMPORTANT NUMBERS Reference and Instruction AT A GLANCE 276.964.7617 [email protected] Circulation / Renewals: 276.964.7265 Terri Kiser Cataloging & Acquisitions Reference / Instruction: 276.964.7738 276.964.7617 [email protected] Evening Services: Debbie Davis 276.964.7265 Circulation & Interlibrary Loan 276.964.7265 Interlibrary Loan: [email protected] 276.964.7265 Nancy Bonney Coordinator of Circulation Library Services: 276.964.7265 276.964.7266 [email protected] Acquisitions: David Butcher 276.964.7630 Circulation 276.964.7265 Cataloging: [email protected] 2017-2018 276.964.7738 Rev. 2/2017 Library Handbook for Students Southwest Virginia Community College P.O. Box SVCC Southwest Virginia Richlands, VA 24641 Community College (800) 822-7822 or (276) 964-7235 V/TDD P.O. Box SVCC http://www.sw.edu Richlands, VA 24641-1101 EOE/AA Pare información en español, Ilame Ud. (276) 964-7751. Pour des renseignements en français, appelez (276) 964–7751. My EMPL ID: APA STYLE (patterns and examples) HOW TO CITE ONLINE ARTICLES & E-BOOKS My SWCC email address: My SWCC username (for Library, Black- Warning: Citation style for online sources is continually evolving. Consult your instructor in choosing the appropriate style and for further guidance. board, SWCC email & Student Information ***************************************************************************** Magazine Article Pattern for APA style: System): [Author last name], [First initial]. [Middle initial]. ([Year], [Month and day]). [Title of article]. [Title of magazine], [Volume number]([Issue number]), [Inclusive page numbers].