CITY UNIVERSITY LONDON Henry, Matthew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macintoshed Libraries 2.0. INSTITUTION Apple Library Users Group, Cupertino, CA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 947 IR 054 450 AUTHOR Vaccaro, Bill, Ed.; Valauskas, Edward J., Ed. TITLE Macintoshed Libraries 2.0. INSTITUTION Apple Library Users Group, Cupertino, CA. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 96p.; For the 1991 volume, see IR 054 451. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Libraries; *Computer Software; Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; *Hypermedia; *Library Automation; Library Instruction; Library Services; *Microcomputers; Public Libraries; Reference Services; School Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Apple Macintosh; HyperCard; Screen Format; Vendors ABSTRACT This annual collection contains 18 papers about the use of Macintosh computers in libraries. Papers include: "The Macintosh as a Wayfinding Tool for Professional Conferences: The LITA '88 HyperCard Stack" (Ann F. Bevilacqua); "Enhancing Library Services with the Macintosh" (Naomi C. Broering); "Scanning Technologies in Libraries" (Steve Cisler); "The Macintosh at the University of Illinois at Chicago Library: Flexibility in a Dynamic Environment" (Kerry L. Cochrane); "How a School Librarian Looked at a Gnawing Problem (and Saw How the Mac and Hypercard Might Solve It)" (Stephen J. D'Elia); "The Macintoshed Media Catalog: Helping People Find What They Need in Spite of LC" (Virginia Gilmore and Layne Nordgren); "The Mac and Power Days at Milne" (Richard D. Johnson); "The USC College Library--A Macintoshed System" (Anne Lynch and Hazel Lord); "Macintosh in the Apple Library: An Update" (Rosanne Macek); "The Macs-imized High School Library Instructional Program" (Carole Martinez and Ruth Windmiller); "The Power To Be Our Best: The Macintosh at the Niles Public Library" (Duncan J. McKenzie); "Taking the Plunge...or, How to Launch a 'Mac-Attack' on a Public Library" (Vickie L. -

Collection Preservation in Library Building Design

Collection Preservation in Library Building Design Collection Preservation in Library Building Design. This material was originally created by Barclay Ogden, Library Preservation Department, University of California, Berkeley. Valuable review and contributions were provided by Edward Dean AIA of SMWM Architecture, San Francisco, and Steven Guttmann of Guttmann + Blaevoet Mechanical Engineers, San Francisco. Illustrations were done by Michael Bulander, Architect, Los Angeles. The publication is provided through the Libris Design Project [http://www.librisdesign.org], supported by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered in California by the State Librarian. Any use of this material should credit the authors and funding source. CONTENTS Page 1. COSTS AND BENEFITS OF COLLECTION PRESERVATION 1 2. COLLECTION PROTECTION 2 2.1 Fire Protection 2 2.2 Water Protection 7 2.3 Theft and Vandalism Protection 9 2.4 Disaster Response and Collection Salvage 9 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL 12 3.1 Relative Humidity Specifications 13 3.2 Temperature Specifications 15 3.3 Stabilizing Relative Humidity and Temperature 15 3.4 Air Pollutants 16 3.5 Light Specifications 17 3.6 Monitoring the Storage Environment 19 4. STACK SHELVING 20 4.1 Shelving 20 4.2 Bookends 21 4.3 Exterior Walls and Placement of Supply Air Ducts 22 4.4 Stack Carpeting 23 5. COMMON PRESERVATION CHALLENGES IN LIBRARY BUILDING PROJECTS 23 5.1 Aesthetics Trump Preservation 23 5.2 Preservation Priorities Get Scrambled 23 5.3 Preservation Costs Energy 23 5.4 Some HVAC Engineers Don't Understand Collection Needs 24 5.5 High-Tech Systems Are Too Smart for Their Own Good 24 5.6 Disasters Happen During Construction 24 5.7 Buildings Below the Water Table Get Wet 25 5.8 Collections Are Moved before the Building Is Ready 25 6. -

TEXAS Library JOURNAL

TexasLibraryJournal VOLUME 88, NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2012 INCLUDES THE BUYERS GUIDE to TLA 2012 Exhibitors TLA MOBILE APP Also in this issue: Conference Overview, D-I-Y Remodeling, and Branding Your Professional Image new from texas Welcome to Utopia Notes from a Small Town By Karen Valby Last Launch Originally published by Spiegel Discovery, Endeavour, Atlantis and Grau and now available in By Dan Winters paperback with a new afterword Powerfully evoking the and reading group guide, this unquenchable American spirit highly acclaimed book takes us of exploration, award-winning into the richly complex life of a photographer Dan Winters small Texas town. chronicles the $15.00 paperback final launches of Discovery, Endeavour, and Atlantis in this stunning photographic tribute to America’s space Displaced Life in the Katrina Diaspora shuttle program. Edited by Lynn Weber and Lori Peek 85 color photos This moving ethnographic ac- $50.00 hardcover count of Hurricane Katrina sur- vivors rebuilding their lives away from the Gulf Coast inaugurates The Katrina Bookshelf, a new series of books that will probe the long-term consequences of Inequity in the Friedrichsburg America’s worst disaster. A Novel The Katrina Bookshelf, Kai Technopolis By Friedrich Armand Strubberg Race, Class, Gender, and the Digital Erikson, Series Editor Translated, annotated, and $24.95 paperback Divide in Austin illustrated by James C. Kearney $55.00 hardcover Edited by Joseph Straubhaar, First published in Jeremiah Germany in 1867, Spence, this fascinating Zeynep autobiographical Tufekci, and novel of German Iranians in Texas Roberta G. immigrants on Migration, Politics, and Ethnic Identity Lentz the antebellum By Mohsen M. -

College and Research Libraries

Destruction of Knowledge: A Study of Journal Mutilation at a Large University Library Constantia Constantinou Book and journal mutilation is a problem for libraries. The rising cost of replacing mutilated books and journals and the availability of out-of-print materials concerns many librarians. This paper examines one type of mutilation-the removal of pages from journal titles at the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library of New York University. The study reviews the related lit erature; it discusses the methodology of the descriptive study on journal mutilation at Bobst Library; it analyzes and interprets the results of the study, makes suggestions that could help reduce the problem, and pro poses other topics for additional research. ot long ago, an e-mail mes new publications, the cost of replac sage circulated among library ing older, heavily used material is a collection staff which dis real concern. As well, several of the cussed the increasing prob items are no longer in print and we lem of book and journal mutilation. The are unable to replace them. I message outlining these issues read as fol would appreciate hearing any ideas lows: for preventing, minimizing or cop ing.with the situation.1 This past term our library staff no ticed an increase in the number of Review of Related Literature books and journal issues that are Libraries realize that book and journal being damaged, e.g., pictures ra mutilation is a growing problem that sim zor[ed] or torn out [and] entire con ply does not go away. It is costly and dis tents removed with only the covers ruptive for both libraries and library us left on the shelves or in nearby gar ers. -

The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service

Quidditas Volume 9 Article 9 1988 The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Platt, F. Jeffrey (1988) "The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service," Quidditas: Vol. 9 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol9/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JRMMRA 9 (1988) The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service by F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University The critical early years of Elizabeth's reign witnessed a watershed in European history. The 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, which ended the long Hapsburg-Valois conflict, resulted in a sudden shift in the focus of international politics from Italy to the uncomfortable proximity of the Low Countries. The arrival there, 30 miles from England's coast, in 1567, of thousands of seasoned Spanish troops presented a military and commer cial threat the English queen could not ignore. Moreover, French control of Calais and their growing interest in supplanting the Spanish presence in the Netherlands represented an even greater menace to England's security. Combined with these ominous developments, the Queen's excommunica tion in May 1570 further strengthened the growing anti-English and anti Protestant sentiment of Counter-Reformation Europe. These circumstances, plus the significantly greater resources of France and Spain, defined England, at best, as a middleweight in a world dominated by two heavyweights. -

1 in THIS CHAPTER We Examine the Early Records of the Bodleian

BUILDING A LIBRARY WITHOUT WALLS: THE EARLY YEARS OF THE BODLEIAN LIBRARY ROBYN ADAMS AND LOUISIANE FERLIER CENTRE FOR EDITING LIVES AND LETTERS BODLEY’S REFOUNDATION OF THE LIBRARY AT OXFORD IN THIS CHAPTER we examine the early records of the Bodleian Library in order to explore the protean administrative processes employed by Sir Thomas Bodley and Thomas James, his first Librarian. These early records yield a glimpse of how various aspects of the library were shaped, and of the attitudes towards books and donors demonstrated by Bodley and James. Our research data extracted from these records reveal bibliographical patterns and physical behaviours which allow us to interrogate the intellectual processes at work in populating the library shelves. Erected, famously, ‘for the publique use of students’, we aim to interrogate the tension of the Bodleian’s role as a public institution promoting and preserving for posterity the muniments of early English religion while at the same time serving an academic community, the principal constituency of which were students. We aim to confront to material evidence this idea of the library for the ‘publique use of students’, and dig deeper to find other sources of motivation for the resurrection of the bibliographical monument that was Bodley’s vision. Following his withdrawal from public service in his political role as diplomatic agent in the Netherlands during the conflict with Spain between 1588 and 1596, Bodley directed elsewhere the administrative energy that had defined his career as a legate.1 His decision to return to Oxford, to refurbish the structure and furnish his newly-constructed presses with books resulted in not only soliciting philanthropic gestures from politically powerful friends and contacts but also a new sort of activity; that of organising a brand new kind of institution. -

Foundations of Cataloging a Sourcebook

Foundations of Cataloging A Sourcebook Edited by Michael Carpenter and Elaine Svenonius 1985 Libraries Unlimited, Inc. • Littleton, Colorado xii- Preface 6. What criteria have been used for making fonn of name decisions in the past? Are they still relevant today? 7. What bibliographic relationships need to be built into a catalog to make it more than just a fmding list? Has thinking on this matter changed over the last 150 years? Criteria for Selection Rules for the Compilation An attempt was made to include in this sourcebook readings that provide intellectual depth and matter for thought. Most of the selected readings are well of the Catalogue known; a few, however, are little read but included as gems that deserve to be known. Panizzi's letter to Lord Ellesmere, for example, reflects in miniature the British Museum whole of the Anglo-American cataloging experience. Inevitably, the selections have an Anglo-American bias; particularly notable by their absence are representatives of the Indian and German schools. Some restriction was necessary to keep the volume to a manageable size, and, since it was felt that the literature written in English and about the Anglo-American tradition would be of most immediate Editor's Introduction interest, it is this writing that is represented. The vo lume includes relatively few recent contributions. This is a consequence of the fact that much recent writing Why should rules for a dead catalog be of interest today? is devo ted to the engineering of online catalogs and to the mechanics of interface, Because the history of cataloging shows that controversies rather than to the more philosophical issues of the purposes of the catalog and the recur, although why these controversies should be perennial means to achieve these. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Understanding and Caring for Bookbindings

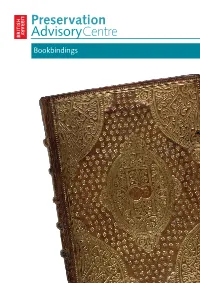

Preservation AdvisoryCentre Bookbindings The Preservation Advisory Centre has been awarded the CILIP Seal of Recognition based on an independent review of the content of its training courses and its engagement with the CILIP Body of Professional Knowledge. The production of this booklet has been supported by Collections Link www.collectionslink.org.uk The Preservation Advisory Centre is supported by: Authors David Pearson, John Mumford, Alison Walker David Pearson is Director of Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London ISBN 0 7123 4982 0 Design The British Library Design Office Cover The Booke of Common Prayer with the Psalter (bound with Bible and psalmes), London 1626. Upper cover, brown calf, tooled in gold. First published November 2006 Revised November 2010 Understanding and caring for bookbindings Developing expertise in recognising and dating bindings is largely a matter of experience, of looking and handling, and many people with responsibility for historic book collections will readily admit that bindings is an area in which they feel they would like to have more detailed knowledge. The key message is that all bindings, however unspectacular they may look, are potentially of interest to historians of the book and cultural historians. Vast quantities of evidence about the ways in which books were sold and circulated in the past has been lost or compromised through the entirely well-intentioned repair work of previous generations, and some of the cheapest and simplest kinds of early bookbindings are now the hardest to find. Provincial collections may contain the work of local bookbinders which will survive nowhere else. Bookbindings are worth preserving not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their value as an intrinsic part of our documentary cultural heritage. -

Antonio Panizzi Professor in London, 1828-1831*

JLIS.it 11, 1 (January 2020) ISSN: 2038-1026 online Open access article licensed under CC-BY DOI: 10.4403/jlis.it-12600 “You will be richer, but I very much doubt that you will be happier”. Antonio Panizzi professor in London, 1828-1831* Stefano Gambari(a), Mauro Guerrini(b) a) Biblioteche di Roma, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2910-9654 b) Università degli Studi di Firenze, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1941-4575 __________ Contact: Stefano Gambari, [email protected]; Mauro Guerrini, [email protected] Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 8 October 2019; First Published: 15 January 2020 __________ ABSTRACT The paper offers an overview of the complex, not easy period in which Antonio Panizzi was teaching at London University (1828-1831), innovatively suggesting that “a uniform program be adopted for the study of all modern languages and literatures” and nevertheless dedicating himself to research with care and passion. In the article, the teaching materials and custom tools he quickly provided to his students for learning italian language and culture are analyzed regarding concept, structure and target: The Elementary Italian Grammar 1828, and two anthologies of prose writings: Extracts from the Italian Prose Writers, 1828, and Stories from Italian Writers with a Literal Interlinear Traduction, 1830. KEYWORDS Italian language; Italian grammar; Italian literature; Teaching materials for italian; University of London; Antonio Panizzi. CITATION Gambari, S., Guerrini., M. “«You will be richer, but I very much doubt that you will be happier». Antonio Panizzi professor in London, 1828-1831.” JLIS.it 11, 1 (January 2020): 73−88. DOI: 10.4403/jlis.it-12600. -

Strategy 2018-2022

BODLEIAN LIBRARIES STRATEGY 2018–2022 Sharing knowledge, inspiring scholarship Advancing learning, research and innovation from the heart of the University of Oxford through curating, collecting and unlocking the world’s information. MESSAGE FROM BODLEY’S LIBRARIAN The Bodleian is currently in its fifth century of serving the University of Oxford and the wider world of scholarship. In 2017 we launched a new strategy; this has been revised in 2018 to be in line with the University’s new strategic plan (www.ox.ac.uk/about/organisation/strategic-plan). This new strategy has been formulated to enable the Bodleian Libraries to achieve three key aims for its work during the period 2018-2022, to: 1. help ensure that the University of Oxford remains at the forefront of academic teaching and research worldwide; 2. contribute leadership to the broader development of the world of information and libraries for society; and 3. provide a sustainable operation of the Libraries. The Bodleian exists to serve the academic community in Oxford and beyond, and it strives to ensure that its collections and services remain of central importance to the current state of scholarship across all of the academic disciplines pursued in the University. It works increasingly collaboratively with other parts of the University: with college libraries and archives, and with our colleagues in GLAM, the University’s Gardens, Libraries and Museums. A key element of the Bodleian’s contribution to Oxford, furthermore, is its broader role as one of the world’s leading libraries. This status rests on the depth and breadth of its collections to enable scholarship across the globe, on the deep connections between the Bodleian and the scholarly community in Oxford, and also on the research prowess of the libraries’ own staff, and the many contributions to scholarship in all disciplines, that the library has made throughout its history, and continues to make. -

Update from the Bodleian Libraries Sarah E Thomas Bodley's Librarian

Update from the Bodleian Libraries Sarah E Thomas Bodley’s Librarian Dear Colleagues, As we enter November and pass the half way mark in Michaelmas Term I want to update you in the first of what I intend to be many informal bulletins about some of the new services and changes taking place across the Bodleian Libraries. I plan to send one of these emails each term, but I’d welcome your feedback on whether or not you find them useful as well as what the frequency should be. 2012/13 is proving to be a busy year. With the construction of the Book Storage Facility completed and over 7 million books, journals, maps, and other archival materials moved, you might think we would have settled down into a routine. However, we are operating our services amidst a sea of change, and this past year we’ve experienced some turbulence. It’s hardly business as usual as our special collections have been camped out in the Lankester Room of the Radcliffe Science Library, and readers consulting Bodley’s maps and music collections are working in Duke Humfrey’s. Well over a hundred staff are dispersed temporarily in rooms in the Old Bodleian, the Clarendon Building, and Osney. Meanwhile, the refurbishment of the New Bodleian is proceeding apace. At the same time we have been undertaking these massive changes, there have been several initiatives on a smaller scale which have been controversial. This newsletter will update you on what’s been happening. I hope that you’ll welcome the information and that you will let me know if you have questions about these or other Bodleian Libraries activities.