Bookshelf by Lydia Pyne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Trails--Book Collecting for Fun, Not Profit Thomas W

Against the Grain Volume 28 | Issue 5 Article 27 2016 Oregon Trails--Book Collecting for Fun, Not Profit Thomas W. Leonhardt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Leonhardt, Thomas W. (2016) "Oregon Trails--Book Collecting for Fun, Not Profit," Against the Grain: Vol. 28: Iss. 5, Article 27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7524 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. ginning with modern cataloging standards (e.g., AACR, MARC format, Book Reviews FRBR, and RDA), the authors go on to focus on underlying principles, from page 50 which are rooted in the need to achieve maximum efficiencies. The limitations of these standards and of others developed specifically to describe digital information objects, such as Encoded Archival Descrip- Alemu, Getaneh and Brett Stevens. An Emergent Theory of tion (EAD), Dublin Core, and Metadata Object Description Schema Digital Library Metadata: Enrich then Filter. Chandos Informa- (MODS) are discussed in detail, and while acknowledging the benefits tion Professional Series. Kidlington, UK: Chandos Publishing, of standards-based, expert-created metadata, the authors contend that it 2015. 9780081003855. 122 pages. $78.95. fails to adequately represent the diversity of views and perspectives of potential users. Additionally, the imperative to “enrich” expert-created Reviewed by Mary Jo Zeter (Latin American and Caribbean metadata with metadata created by users is not only a practical response Studies Bibliographer, Michigan State University Libraries) to the rapidly increasing amount of digital information, argue the au- thors, it is necessary in order to fully optimize the potential of Linked <[email protected]> Data. -

Macintoshed Libraries 2.0. INSTITUTION Apple Library Users Group, Cupertino, CA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 947 IR 054 450 AUTHOR Vaccaro, Bill, Ed.; Valauskas, Edward J., Ed. TITLE Macintoshed Libraries 2.0. INSTITUTION Apple Library Users Group, Cupertino, CA. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 96p.; For the 1991 volume, see IR 054 451. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Libraries; *Computer Software; Elementary Secondary Education; Higher Education; *Hypermedia; *Library Automation; Library Instruction; Library Services; *Microcomputers; Public Libraries; Reference Services; School Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Apple Macintosh; HyperCard; Screen Format; Vendors ABSTRACT This annual collection contains 18 papers about the use of Macintosh computers in libraries. Papers include: "The Macintosh as a Wayfinding Tool for Professional Conferences: The LITA '88 HyperCard Stack" (Ann F. Bevilacqua); "Enhancing Library Services with the Macintosh" (Naomi C. Broering); "Scanning Technologies in Libraries" (Steve Cisler); "The Macintosh at the University of Illinois at Chicago Library: Flexibility in a Dynamic Environment" (Kerry L. Cochrane); "How a School Librarian Looked at a Gnawing Problem (and Saw How the Mac and Hypercard Might Solve It)" (Stephen J. D'Elia); "The Macintoshed Media Catalog: Helping People Find What They Need in Spite of LC" (Virginia Gilmore and Layne Nordgren); "The Mac and Power Days at Milne" (Richard D. Johnson); "The USC College Library--A Macintoshed System" (Anne Lynch and Hazel Lord); "Macintosh in the Apple Library: An Update" (Rosanne Macek); "The Macs-imized High School Library Instructional Program" (Carole Martinez and Ruth Windmiller); "The Power To Be Our Best: The Macintosh at the Niles Public Library" (Duncan J. McKenzie); "Taking the Plunge...or, How to Launch a 'Mac-Attack' on a Public Library" (Vickie L. -

Collection Preservation in Library Building Design

Collection Preservation in Library Building Design Collection Preservation in Library Building Design. This material was originally created by Barclay Ogden, Library Preservation Department, University of California, Berkeley. Valuable review and contributions were provided by Edward Dean AIA of SMWM Architecture, San Francisco, and Steven Guttmann of Guttmann + Blaevoet Mechanical Engineers, San Francisco. Illustrations were done by Michael Bulander, Architect, Los Angeles. The publication is provided through the Libris Design Project [http://www.librisdesign.org], supported by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services under the provisions of the Library Services and Technology Act, administered in California by the State Librarian. Any use of this material should credit the authors and funding source. CONTENTS Page 1. COSTS AND BENEFITS OF COLLECTION PRESERVATION 1 2. COLLECTION PROTECTION 2 2.1 Fire Protection 2 2.2 Water Protection 7 2.3 Theft and Vandalism Protection 9 2.4 Disaster Response and Collection Salvage 9 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL 12 3.1 Relative Humidity Specifications 13 3.2 Temperature Specifications 15 3.3 Stabilizing Relative Humidity and Temperature 15 3.4 Air Pollutants 16 3.5 Light Specifications 17 3.6 Monitoring the Storage Environment 19 4. STACK SHELVING 20 4.1 Shelving 20 4.2 Bookends 21 4.3 Exterior Walls and Placement of Supply Air Ducts 22 4.4 Stack Carpeting 23 5. COMMON PRESERVATION CHALLENGES IN LIBRARY BUILDING PROJECTS 23 5.1 Aesthetics Trump Preservation 23 5.2 Preservation Priorities Get Scrambled 23 5.3 Preservation Costs Energy 23 5.4 Some HVAC Engineers Don't Understand Collection Needs 24 5.5 High-Tech Systems Are Too Smart for Their Own Good 24 5.6 Disasters Happen During Construction 24 5.7 Buildings Below the Water Table Get Wet 25 5.8 Collections Are Moved before the Building Is Ready 25 6. -

TEXAS Library JOURNAL

TexasLibraryJournal VOLUME 88, NUMBER 1 • SPRING 2012 INCLUDES THE BUYERS GUIDE to TLA 2012 Exhibitors TLA MOBILE APP Also in this issue: Conference Overview, D-I-Y Remodeling, and Branding Your Professional Image new from texas Welcome to Utopia Notes from a Small Town By Karen Valby Last Launch Originally published by Spiegel Discovery, Endeavour, Atlantis and Grau and now available in By Dan Winters paperback with a new afterword Powerfully evoking the and reading group guide, this unquenchable American spirit highly acclaimed book takes us of exploration, award-winning into the richly complex life of a photographer Dan Winters small Texas town. chronicles the $15.00 paperback final launches of Discovery, Endeavour, and Atlantis in this stunning photographic tribute to America’s space Displaced Life in the Katrina Diaspora shuttle program. Edited by Lynn Weber and Lori Peek 85 color photos This moving ethnographic ac- $50.00 hardcover count of Hurricane Katrina sur- vivors rebuilding their lives away from the Gulf Coast inaugurates The Katrina Bookshelf, a new series of books that will probe the long-term consequences of Inequity in the Friedrichsburg America’s worst disaster. A Novel The Katrina Bookshelf, Kai Technopolis By Friedrich Armand Strubberg Race, Class, Gender, and the Digital Erikson, Series Editor Translated, annotated, and $24.95 paperback Divide in Austin illustrated by James C. Kearney $55.00 hardcover Edited by Joseph Straubhaar, First published in Jeremiah Germany in 1867, Spence, this fascinating Zeynep autobiographical Tufekci, and novel of German Iranians in Texas Roberta G. immigrants on Migration, Politics, and Ethnic Identity Lentz the antebellum By Mohsen M. -

College and Research Libraries

Destruction of Knowledge: A Study of Journal Mutilation at a Large University Library Constantia Constantinou Book and journal mutilation is a problem for libraries. The rising cost of replacing mutilated books and journals and the availability of out-of-print materials concerns many librarians. This paper examines one type of mutilation-the removal of pages from journal titles at the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library of New York University. The study reviews the related lit erature; it discusses the methodology of the descriptive study on journal mutilation at Bobst Library; it analyzes and interprets the results of the study, makes suggestions that could help reduce the problem, and pro poses other topics for additional research. ot long ago, an e-mail mes new publications, the cost of replac sage circulated among library ing older, heavily used material is a collection staff which dis real concern. As well, several of the cussed the increasing prob items are no longer in print and we lem of book and journal mutilation. The are unable to replace them. I message outlining these issues read as fol would appreciate hearing any ideas lows: for preventing, minimizing or cop ing.with the situation.1 This past term our library staff no ticed an increase in the number of Review of Related Literature books and journal issues that are Libraries realize that book and journal being damaged, e.g., pictures ra mutilation is a growing problem that sim zor[ed] or torn out [and] entire con ply does not go away. It is costly and dis tents removed with only the covers ruptive for both libraries and library us left on the shelves or in nearby gar ers. -

Arrangement and Maintenance of Library Material MODULE - 3 ORGANISATION of INFORMATION SOURCES

Arrangement and Maintenance of Library Material MODULE - 3 ORGANISATION OF INFORMATION SOURCES 11 Notes ARRANGEMENT AND MAINTENANCE OF LIBRARY MATERIAL 11.1 INTRODUCTION In this lesson, we will discuss the issues related to organization and maintenance of library material. You will be told how materials have to be arranged on library shelves and how the arrangement of books differs from the arrangement of periodicals. The library material needs to be maintained on routine basis. Maintenance of library material involves kinds of stacking, shelf arrangement, cleaning, shelving, stock verification and weeding of unwanted material. Binding of documents will also be discussed as it is essential for care and repair of documents for their long life. 11.2 OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to :– describe various ways to arrange books and periodicals ; identify various kinds of library stacks; explain the shelving order of books; explain arrangement of periodicals; describe the activities related to care of documents; highlight the importance of mending and binding of library books and periodicals; illustrate the role of stock verification and weeding of documents; LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE 187 MODULE - 3 Arrangement and Maintenance of Library Material ORGANISATION OF INFORMATION SOURCES justify the need for security of library documents; and give illustrations of library displays. 11.3 MAINTENANCE WORK Notes In every library, maintenance of library material involves continuous monitoring of the stack room, displaying of new material on the display racks and arrangement of the books and periodicals on the shelves after use. Besides these, the material has to be dusted and cleaned at periodic intervals. -

The Modern History of the Library Movement and Reading Campaign in Korea

Date : 27/06/2006 The modern history of the library movement and reading campaign in Korea Yong-jae Lee Assistant Professor Department of Library, Archive and Information Studies Pusan National University, 30 Janjeon-dong, Geumjeong-gu, Pusan, 609-735 Republic of Korea And Jae-soon Jo, Librarian The Korean National University of Arts Library San 1-5, Seokgwang-dong, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul, 136-716 Republic of Korea Meeting: 119 Library History Simultaneous Interpretation: No WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 72ND IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 20-24 August 2006, Seoul, Korea http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla72/index.htm ABSTRACT This paper explores the history of library movement and reading campaign in Korea since 1900. Korean people tried in many ways to establish their own libraries in 20th century. Many library thinkers, intellectuals, and librarians have struggled to build 1 modern libraries in communities or nationwide. Although Korea has a brilliant history of record and print, it has been so hard to establish libraries for the Korean people during last century. The Korean libraries have endured hardships such as Japanese colonialism, Korean War, and military dictatorship. This paper examines the Korean people’s efforts to establish libraries, and it looks into the history of library movement in Korea. And also this paper introduces the recent reading campaigns such as ‘Bookstart’, ‘One Book One City’. With historical lessons suggested in this paper, people may have some insight to make and develop libraries in Korea. 2 1. Introduction Korean public libraries in the 20th Century grew by undergoing history of formidable obstacles. -

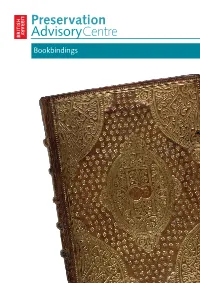

Understanding and Caring for Bookbindings

Preservation AdvisoryCentre Bookbindings The Preservation Advisory Centre has been awarded the CILIP Seal of Recognition based on an independent review of the content of its training courses and its engagement with the CILIP Body of Professional Knowledge. The production of this booklet has been supported by Collections Link www.collectionslink.org.uk The Preservation Advisory Centre is supported by: Authors David Pearson, John Mumford, Alison Walker David Pearson is Director of Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London ISBN 0 7123 4982 0 Design The British Library Design Office Cover The Booke of Common Prayer with the Psalter (bound with Bible and psalmes), London 1626. Upper cover, brown calf, tooled in gold. First published November 2006 Revised November 2010 Understanding and caring for bookbindings Developing expertise in recognising and dating bindings is largely a matter of experience, of looking and handling, and many people with responsibility for historic book collections will readily admit that bindings is an area in which they feel they would like to have more detailed knowledge. The key message is that all bindings, however unspectacular they may look, are potentially of interest to historians of the book and cultural historians. Vast quantities of evidence about the ways in which books were sold and circulated in the past has been lost or compromised through the entirely well-intentioned repair work of previous generations, and some of the cheapest and simplest kinds of early bookbindings are now the hardest to find. Provincial collections may contain the work of local bookbinders which will survive nowhere else. Bookbindings are worth preserving not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their value as an intrinsic part of our documentary cultural heritage. -

Read Ebook « Curse of the Devil

7PUIRNK4IJJA Kindle ~ Curse of the Devil Curse of th e Devil Filesize: 5.1 MB Reviews This publication is wonderful. It normally is not going to expense too much. Its been printed in an extremely straightforward way in fact it is merely following i finished reading this publication where actually transformed me, modify the way i really believe. (Russell Adams DDS) DISCLAIMER | DMCA PZ5M3TAH77F1 > eBook \ Curse of the Devil CURSE OF THE DEVIL Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016. PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from US within 10 to 14 business days. THIS BOOK IS PRINTED ON DEMAND. Established seller since 2000. Read Curse of the Devil Online Download PDF Curse of the Devil DHH6SCHEMAGS \\ Book / Curse of the Devil Oth er PDFs The Curse of the Translucent Monster! (in Color): Warning: Not a Kids Story!! Createspace, United States, 2013. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 203 x 127 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.Have you been searching for a great, horrifying read? Something that will really... Read eBook » Index to the Classified Subject Catalogue of the Bualo Library; The Whole System Being Adopted from the Classification and Subject Index of Mr. Melvil Dewey, with Some Modifications . Rarebooksclub.com, United States, 2013. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 246 x 189 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.This historic book may have numerous typos and missing text. Purchasers can usually... Read eBook » Games with Books : 28 of the Best Childrens Books and How to Use Them to Help Your Child Learn - From Preschool to Third Grade Book Condition: Brand New. -

Exhibition Guide

Exhibition Guide February 7, 2019 Contents Illumination to Illustration: Art of the Book ......................................................................................................................... - 2 - Illumination ............................................................................................................................................................................. - 3 - Woodcuts ............................................................................................................................................................................... - 6 - Engravings/Etchings ........................................................................................................................................................... - 10 - Illustration ............................................................................................................................................................................. - 13 - Photography ........................................................................................................................................................................ - 16 - Fine Art Press ...................................................................................................................................................................... - 19 - Children’s ............................................................................................................................................................................. - 24 - Graphic Novels -

THE BOOKCASE Agawam Public Library’S Newsletter Edited by Wendy Mcananama April 2015 I Find Television Very Educating

THE BOOKCASE Agawam Public Library’s Newsletter Edited by Wendy McAnanama April 2015 I find television very educating. Every time somebody turns on the set, I go into the other room and read a book. ~ Groucho Marx National Library Week is April 12-18 AuthorTalk with Janet Barrett Trash Talkin’ with Nancy They Called Her Reckless (and Helga the Hen)! uthor Janet Barrett will visit the Former Agawam High teacher and current st library on Tuesday, April 21 at environmental blogger Nancy Bobskill will A7:00 to read from and discuss her visit the APL on Thursday, April 9th at 7:00 novel They Called Her Reckless. For more with her chicken purse “Helga the Hen.” info visit www.theycalledherreckless.com. Together they will teach how simple actions decrease waste that builds up in our When U.S. Marine Regiment’s Recoilless Rifle landfills, incinerators, rivers and oceans. Platoon acquired a small Korean pony to haul Learn why these solutions not only help ammunition up the steep hills to the front humans but other animals and their line, what they got was a real-life hero, habitats as well. Reckless, a warhorse who stood with her buddies for two years during the Korean War, The first 50 people saving many lives, raising spirits and winning (1 per household) who the love and respect of all who knew her. sign up and attend This book was made possible by the this event will receive contributions of over 50 Marines. a free kitchen compost bucket, courtesy of Please register by calling 789-1550 x4 or the Agawam DPW! Call 789-1550 x4 or go online at www.agawamlibrary.org. -

Ken Sanders Rare Books Kicks Off 10Th Anniversary Celebration

The ABN E WSLETTEA AR VOLUME EIGHTEEN, NUMBER 4 ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLERS' ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA FALL 2007 INSIDE: MAC Chapter hosts Digital Photo Seminar................................................PAGE 3 A Collector’s Primer to the Wonders of Fore-edge Painting By Jeff Weber One of the most unusual types of book decoration is fore-edge paintings. These are books which have one or more of the top, fore or bottom edge painted – usu- ally with watercolors. The typical form is a book with a single fanned fore-edge painting. In the twentieth century other forms have developed, including the Ken Sanders (center) celebrates with friends at the kick-off of several days of double fore-edge or even the remarkable events feting the anniversary of his shop in Salt Lake City. six-way painting where all three sides of the book have a double. Other forms include the side-by-side painting (two scenes on the single edge), and the split- Ken Sanders Rare Books kicks off double (splits the book in half and shows a scene on each fanned side half-way 10th Anniversary Celebration up the book edge). There is the vertical painting which is found on occasion. The by Annie Mazes first editions and comic books as well as fanned single edge painting is the most Ken Sanders, a long-time active member working on and off at Sam Weller’s, a common form. When the book is closed of the ABAA, and his daughter Melissa, well established independent bookstore in the painting disappears! This is because celebrated the 10th anniversary of their Salt Lake City.