Sandra Hindman Ariane Bergeron-Foote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How We Got Our Bible Part Three: the Text of the New Testament

How We Got Our Bible Part Three: The Text of the New Testament I. The Nature of New Testament Manuscripts A. Early biblical manuscripts were written on papyrus. B. By the 3d century parchment (leather) became the standard paper for biblical manuscripts. C. Writing was done with pen and ink. The ink was usually brown or black. D. Initially New Testament books were written on Scrolls. E. Around the beginning of the 2d century the codex (modern book) became the main book format. II. The Styles of Writing in New Testament Manuscripts A. Cursive (minuscule) Handwriting B. All-Capitals (uncial) C. Because of the cost of parchment many documents were scraped and washed to be reused for other literature. These are called Palimpsests. They are biblical manuscripts that are written on reused parchment. Of the 263 uncial manuscripts of the New Testament 63 are palimpsests. D. In the early centuries of Christianity the gospels were divided into regular readings for services. Scribes marked the beginning and end of these readings so the lector (reader) knew where to begin and end. These manuscripts of the gospels are called lectionaries (Lindisfarne Gospels). E. The advent of monasteries created a class of monks who became scribes. They worked standing at a writing desk in a room called a scriptorium. This was difficult and tedious work. Some monks even added little sentences at the end of manuscripts such as, “The end of the book; thanks be to God.” F. The monks also added footnotes called colophons which include the name of the scribe and sometimes the date and place of writing. -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

How Is a Torah Made?

How is a Torah made? By Rabbi Amy R. Scheineman The scribe prepares parchment sheets While printed editions of the Torah abound, in both Hebrew and English translation, and with many different commentaries, when the Torah is read in the synagogue on Shabbat and holidays, it is read from a hand-written scroll, called a Sefer Torah, in keeping with age-old tradition. It takes several months, and often as a long as a year to complete one Sefer Torah. The Sefer Torah is written by a scribe, special trained for this holy task, on sheets of parchment. The parchment must derive from a kosher animal, usually a cow, and is meticulously prepared by the scribe, who first soaks the skin in lime water to remove hairs, and then stretches the skin over a wooden frame to dry. The scribe scrapes the skin while it is stretched over the wooden frame to remove more hair and smooths the surface of the skin in preparation for writing on it with the use of a sanding machine. When the skin is dry, the scribe cuts it into a rectangle. The scribe must prepare many such skins because a Sefer Torah usually contains 248 columns, and one rectangle of parchment yields space for three or four columns. Thus a Sefer Torah may require at more than 80 skins in all. When the parchment sheets are ready, the scribe marks out lines and columns using a stylus, which makes a mark in the skin that has no color, much as if you ran your fingernail across a sheet of paper. -

Fellows Cases/Statements

The Once and Future Book Buchanan Library Fellows ~ Fall 2017 Incunables: The Original First Editions Some of the oldest books on earth, incunables are books printed before the year 1501. Taken from the Latin word, incunabulum or “in the cradle,” these are the first books actually printed in movable type. The incunabular aGe focused on many thinGs, one of which was the past. Many incunables were written about classic literature and theoloGy. In this case, one sees an epic Latin poem about Roman history and a commentary on the Book of Isaiah. This case spotliGhts some of the oldest books we have here in the Vanderbilt Libraries. Located in the Special Collections section in the Central Library, I wanted to focus on a type of book called an incunabulum, or incunables for plural- which are books written before the year 1501 AD. One of the pieces was published in 1492 and features a printer’s device called the colophon which is the identifyinG mark of a particular publisher. The second book in the exhibit is an incunabulum published in 1495, and features vellum (animal skin) tabs, like you miGht see in some dictionaries and other reference books. It also features a full-paGe woodcut of Jesus Christ and the Tree of Jesse, which oriGinates to the Book of Isaiah in the Bible. Binding: Bound to the Past, Looking to the Future Each and every book tell its reader a story. Most books rely upon the words written inside to take them on a journey, but what does the outside of the book reveal about the adventure? The unique role that a book’s bindinG plays in its holistic story is examined and explored in this case. -

The Nature of Hellenistic Domestic Sculpture in Its Cultural and Spatial Contexts

THE NATURE OF HELLENISTIC DOMESTIC SCULPTURE IN ITS CULTURAL AND SPATIAL CONTEXTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Craig I. Hardiman, B.Comm., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Mark D. Fullerton, Advisor Dr. Timothy J. McNiven _______________________________ Advisor Dr. Stephen V. Tracy Graduate Program in the History of Art Copyright by Craig I. Hardiman 2005 ABSTRACT This dissertation marks the first synthetic and contextual analysis of domestic sculpture for the whole of the Hellenistic period (323 BCE – 31 BCE). Prior to this study, Hellenistic domestic sculpture had been examined from a broadly literary perspective or had been the focus of smaller regional or site-specific studies. Rather than taking any one approach, this dissertation examines both the literary testimonia and the material record in order to develop as full a picture as possible for the location, function and meaning(s) of these pieces. The study begins with a reconsideration of the literary evidence. The testimonia deal chiefly with the residences of the Hellenistic kings and their conspicuous displays of wealth in the most public rooms in the home, namely courtyards and dining rooms. Following this, the material evidence from the Greek mainland and Asia Minor is considered. The general evidence supports the literary testimonia’s location for these sculptures. In addition, several individual examples offer insights into the sophistication of domestic decorative programs among the Greeks, something usually associated with the Romans. -

College and Research Libraries

Destruction of Knowledge: A Study of Journal Mutilation at a Large University Library Constantia Constantinou Book and journal mutilation is a problem for libraries. The rising cost of replacing mutilated books and journals and the availability of out-of-print materials concerns many librarians. This paper examines one type of mutilation-the removal of pages from journal titles at the Elmer Holmes Bobst Library of New York University. The study reviews the related lit erature; it discusses the methodology of the descriptive study on journal mutilation at Bobst Library; it analyzes and interprets the results of the study, makes suggestions that could help reduce the problem, and pro poses other topics for additional research. ot long ago, an e-mail mes new publications, the cost of replac sage circulated among library ing older, heavily used material is a collection staff which dis real concern. As well, several of the cussed the increasing prob items are no longer in print and we lem of book and journal mutilation. The are unable to replace them. I message outlining these issues read as fol would appreciate hearing any ideas lows: for preventing, minimizing or cop ing.with the situation.1 This past term our library staff no ticed an increase in the number of Review of Related Literature books and journal issues that are Libraries realize that book and journal being damaged, e.g., pictures ra mutilation is a growing problem that sim zor[ed] or torn out [and] entire con ply does not go away. It is costly and dis tents removed with only the covers ruptive for both libraries and library us left on the shelves or in nearby gar ers. -

Special Catalogue 21

Special Catalogue 21 Marbling OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Special Catalogue 21 includes 54 items covering the history, traditions, methods, and extraordinary variety of the art of marbling. From its early origins in China and Japan to its migration to Turkey in the 15th century and Europe in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, marbling is the most colorful and fanciful aspect of book design. It is usually created without regard to the content of the book it decorates, but sometimes, as in the glorious work of Nedim Sönmez (items 39-44), it IS the book. I invite you to luxuriate in the wonderful examples and fascinating writings about marbling contained in these pages. As always, please feel free to browse our inventory online at www.oakknoll.com. Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. -

Classical Jewish Texts, from Parchment to Internet 1Qisaa

11 December 2017 Scroll Down: Classical Jewish Texts, Aleppo Codex from Parchment to Internet c. 930 Tiberias Gary A. Rendsburg http://aleppocodex.org/ Rutgers University Sample page shows portions Allen and Joan Bildner Center of Ezekiel 2‐3 for the Study of Jewish Life Rutgers University 4 December 2017 St. Petersburg (Leningrad) Codex 1009 / Tiberias (digital images not Aleppo Codex / c. 930 / Tiberias available online) Sample verse: Joshua 1:1 Sample page Genesis 1 ַו ְי ִ֗הי ַא ֲחֵ ֛רי ֥מוֹת ֹמ ֶ ֖שׁה ֶ ֣ע ֶבד ְי ָ ֑הוה ַו ֤יּ ֹ ֶאמר ְי ָהו ֙ה ֶא ְל־י ֻ ֣הוֹשׁ ַע ִבּ ֔ן־נוּן ְמ ָשֵׁ ֥רת ֹמ ֶ ֖שׁה ֵל ֽ ֹאמר׃ Digital Dead Sea Scrolls / Google / Israel Museum 1QIsaa The Great Isaiah Scroll Isaiah 6:3 (1QIsaa): Holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, all the earth is filled with his glory. Isaiah 6:3 (Masoretic Text): http://dss.collections.imj.org.il/ Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, all the earth is filled with his glory. 1 11 December 2017 Isaiah 6:3 (1QIsaa): Holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, all the earth is filled with his glory. Isaiah 6:3 (Masoretic Text): http://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/about‐the‐project/the‐digital‐library Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, all the earth is filled with his glory. 4Q394 = 4QMMTa fragments 4Q271 = 4QDf – Damascus Document Mishna Kaufmann Manuscript A50 (Budapest) Italy, c. 1200 http://kaufmann.mtak.hu/ en/ms50/ms50‐coll1.htm Ben Sira, c. 180 B.C.E. – http://www.bensira.org/ 2 11 December 2017 Mishna Parma Manuscript, Biblioteca Palatina 3173 (De Rossi 138) Italy, 1073 Mishna Manuscript / c. -

The History, Printing, and Editing of the Returne from Pernassus

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1-2009 The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus Christopher A. Adams College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Adams, Christopher A., "The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 237. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/237 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English from The College of William and Mary by Christopher A. Adams Accepted for____________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors ) _________________________ ___________________________ Paula Blank , Director Monica Potkay , Committee Chair English Department English Department _________________________ ___________________________ Erin Minear George Greenia English Department Modern Language Department Williamsburg, VA December, 2008 1 The History, Printing, and Editing of The Returne from Pernassus 2 Dominus illuminatio mea -ceiling panels of Duke Humfrey’s Library, Oxford 3 Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to my former adviser, Dr. R. Carter Hailey, for starting me on this pilgrimage with the Parnassus plays. He not only introduced me to the world of Parnassus , but also to the wider world of bibliography. Through his help and guidance I have discovered a fascinating field of research. -

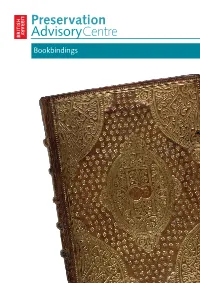

Understanding and Caring for Bookbindings

Preservation AdvisoryCentre Bookbindings The Preservation Advisory Centre has been awarded the CILIP Seal of Recognition based on an independent review of the content of its training courses and its engagement with the CILIP Body of Professional Knowledge. The production of this booklet has been supported by Collections Link www.collectionslink.org.uk The Preservation Advisory Centre is supported by: Authors David Pearson, John Mumford, Alison Walker David Pearson is Director of Libraries, Archives and Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London ISBN 0 7123 4982 0 Design The British Library Design Office Cover The Booke of Common Prayer with the Psalter (bound with Bible and psalmes), London 1626. Upper cover, brown calf, tooled in gold. First published November 2006 Revised November 2010 Understanding and caring for bookbindings Developing expertise in recognising and dating bindings is largely a matter of experience, of looking and handling, and many people with responsibility for historic book collections will readily admit that bindings is an area in which they feel they would like to have more detailed knowledge. The key message is that all bindings, however unspectacular they may look, are potentially of interest to historians of the book and cultural historians. Vast quantities of evidence about the ways in which books were sold and circulated in the past has been lost or compromised through the entirely well-intentioned repair work of previous generations, and some of the cheapest and simplest kinds of early bookbindings are now the hardest to find. Provincial collections may contain the work of local bookbinders which will survive nowhere else. Bookbindings are worth preserving not only for their aesthetic qualities but for their value as an intrinsic part of our documentary cultural heritage. -

The History of Books and Libraries in Bohemia

Digital Editing of Medieval Manuscripts - Intellectual Output 1: Resources for Editing Medieval Texts (Paleography, Codicology, Philology) The history of books and libraries in Bohemia Michal Dragoun (Charles Univeristy in Prague) While books were initially rare in medieval Bohemia, they would come to play an important role in the lives of all social classes by the end of the Middle Ages. The pace of that advancement was not, however, constant. Many factors contributed to spread of books and to their use, some of them pushed the advancement forward significantly, others less significantly. Books were initially a monopoly of the Church and its institutions but gradually, the circle of book users extended to the laity and more and more texts came to be written in vernacular languages. Acknowledging the abundance or research into medieval books and libraries more generally, this overview will comment only on the most significant moments in the book culture of medieval Bohemia. There are two fundamental turning points in the history of Medieval Bohemian book culture – these were the establishment of a university in Prague, and the Hussite Reformation. To provide a brief overview of types of libraries, it is necessary to categorize them and study the development of individual categories. In any case, the Hussite period was the real turning point for a number of them. Sources The sheer abundance of sources provides the basis for a comprehensive overview of Bohemian book culture. The manuscripts themselves are the most significant source. However, the catalogues used to study Bohemian collections tend to be very old. As a result, the records are often incomplete and contextual information is often unavailable. -

4 September Books

book reviews A sense of place The Mapping of North America by Philip D. Burden Raleigh Publications, 46 Talbot Road, Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire WD3 1HE, UK (US office: PO Box 16910, Stamford, Connecticut 06905): 1996. Pp. 568. $195, £120 Jared M. Diamond Today, no prudent motorist, sailor, pilot or hiker sets out into unfamiliar terrain without a printed map. We of the twentieth century take this dependence of travel on maps so completely for granted that we forget how recent it is. The first printed maps date only from the 1470s, a mere two decades after Gutenberg’s perfection of printing with movable type around 1455. Techniques of mapmaking evolved rapidly thereafter. So the most revolutionary change in the history of cartography coincides with the most revolutionary change in Europeans’ Abraham Ortelius’s classic map of the American continents published in Antwerp in 1570. knowledge of world geography, following Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the beliefs that California is an island, that north- no longer existed, having been destroyed by Americas in 1492. west America has a land connection to Siberia, European-born epidemic diseases spread The earliest sketch map of any part of the that a strait separates Central America from from contacts with de Soto and from Euro- Americas dates from 1492 or 1493; the earli- South America, and that the Amazon River pean visitors to the coast — diseases to which est preserved printed map of the Americas flows northwards rather than eastwards. Ini- Europeans had acquired genetic and from 1506. The succession of printed New tially less obvious, but even more important, immune resistance through a long history of World maps that followed is triply interest- is the book’s relevance to the fields of anthro- exposure, but to which Native Americans ing: it illustrates the development of carto- pology, biology, epidemiology and linguistics.