Patriotic Homosocial Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Engagement Through Text Sound Poetry

Wesleyan ♦ University Political Voices: Political Engagement Through Text Sound Poetry By Celeste Hutchins Faculty Advisor: Ron Kuivila A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Middletown, Connecticut May 2005 Text Sound Poetry I created several pieces using manipulated speech recordings, starting in the fall of 2003. After completing some of these pieces, I became aware of Text Sound Poetry as a well-defined genre involving similar passages between language and sound. To find out more about this genre, I listened to Other Mind’s re-release of 10 + 2: 12 American Text Sound Pieces, the re-released OU archives and Terre Thaemlitz’s album Interstices. Text Sound seems to be especially well suited to political expression. Often, a political work suffers a tension between the political/text content and the musical content. Either the political message or the music often must be sacrificed. However, in Text Sound, the text content is the musical content. Composers like Sten Hanson, Steve Reich and Terre Thaemlitz are able to create pieces where complaints about the Vietnam War, police brutality, and gender discrimination form the substance of the piece. To engage the piece is to engage the political content. Reich’s pieces are less obvious than Hanson and Thaemlitz. The loop process he uses in “Its Gonna Rain” is auditorially interesting, but the meaning of the piece is not immediately clear to a modern listener. Many discussions of his pieces eliminate the political content and focus on the process. Before I did research on this piece I was disturbed by the implications of a white composer taking the words of an African American and obscuring them until the content was lost to the process. -

2010 Program Guide

NCORE Program and Resource Guide 23rd Annual National Conference on Race & ® 2010 The Southwest Center for Human Relations Studies Public and Community Services Division College of Continuing Education University OUTREACH The University of Oklahoma 3200 Marshall Avenue, Suite 290 Norman, Oklahoma 73072 The University of Oklahoma is an equal opportunity institution. Ethnicity in American Higher Education Accommodations on the basis of disability are available by calling (405) 325-3694. PROGRAM AND RESOURCE GUIDE 23rd Annual National Conference on Race & Ethnicity in ® (NCORE American Higher Education® June 1 through June 5, 2010 ✦ National Harbor, Maryland ® Sponsored by 2010) The Southwest Center for Human Relations Studies Public and Community Services Division ✦ College of Continuing Education ✦ University Outreach THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE The Southwest Center for Human Relations Studies National Advisory Committee (NAC) The Executive Committee of the Southwest Center for Human Relations Studies serves as the primary planning body for the Annual National Conference National Conference on Race & Ethnicity in American Higher Education® on Race & Ethnicity in American Higher Education (NCORE®). The Executive Committee encourages direct, broadly based input into the planning process from all conference participants through the conference evaluation process, discussion, and other written and verbal communication. NCORE 2008-NCORE 2010 David Owen, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Appointment NCORE 2011-NCORE 2013 Philosophy Joel Arvizo, Project Coordinator University of Louisville—Louisville, KY Ziola Airall, Ph.D., Assistant Vice President Office for Diversity and Community Outreach Division Student Affairs Richard Allen, Ph.D. Richard E. Hilbert, Ph.D. Lotsee F. Patterson, Ph.D. The University of Utah—Salt Lake City, UT Deborah Pace, Director Employer Relations Duke University—Durham, NC Policy Analyst Professor Emeritus Professor Western New England College—Springfield, Mass Kim Lee Halula, Ph.D., Associate Dean Andrew T. -

Download a PDF of the 2021-2022 Catalog

About Middlesex Community College mxcc.edu/catalog/about/ Founded in 1966 as a branch campus of Manchester Community College, Middlesex Community College became an independent member of the Community College System in 1968. At the outset, the college operated principally in space rented from Middletown Public Schools and loaned by Connecticut Valley Hospital. In 1973, the college moved to its present 35-acre campus, which overlooks the scenic Connecticut River and the city of Middletown. MxCC is conveniently located in central Connecticut and is easily accessible via major interstates. Our college and our community are partners in a tradition of shaping the future, one person at a time. We believe our success depends upon our ability to treat others with respect, educate the whole person, recognize that each individual is vital to our mission, and develop programs and services responsive to the current and changing needs of our community. MxCC believes that a college education should be available to everyone and is committed to providing excellence in teaching as well as personal support in developing the genius of each student. An open admissions college, MxCC awards associate degrees and certificates in more than 70 programs which lead to further study, employment, and active citizenship. In addition, the college shares its resources and addresses community needs through numerous credit and non-credit courses, business programs, cultural activities, and special events. Faculty and staff are dedicated to helping students achieve their academic, professional, and career potentials. This support is a continual process that recognizes 1/3 student diversity in both background and learning ability. -

The Cuba Chronicles

cuba https://www.racewalking.org/cuba.htm The Cuba Chronicles A Travel Log from an Altitude Training Camp in the Wilds of New Mexico ©1998 Dave McGovern--Dave's World Class These reports were originally sent to the [email protected] mailing list, hence the odd format. Wigglers; First off, It's been called to my attention that I've made no effort to tell the world I'm going to be conducting one of my World Class clinics in conjunction with the National 10km in Niagara Falls in July. Details on my web site at surf.to/worldclass. Secondly, what's been going on in my life... Several months ago when Mike Rohl called and asked if I'd like to join him for a high-altitude training camp outside Albuquerque, the "What the Hell, Why Not?" side of my brain pistol-whipped the rational side and I agreed to the deal": 5 weeks living in a free cabin at 8,500' outside of Cuba, NM with thrice weekly trips into Albuquerque to get in our quality speed work at a more reasonable elevation. When Mike called from Albuquerque a few weeks before my arrival with the news that the cabin was stilled snowed in and he was staying with his saint of a wife Michelle and their three kids at Judy Climer's house "for a while" it still didn't register that this was doomed to be another "we'll laugh about this in 20 years" Rohl/McGovern racewalking fiasco... Mike and family finally gave up on the original cabin last week and rented a somewhat smaller, lime green two bed/1bath box plunked down in the middle of a muddy cow flop and gopher hole ridden field somewhere in the Jemez Mountains above the non-town of Cuba, NM. -

Discipleship Booklet

Following Christ Nathan E. Brown COMEAFTERME.COM Birmingham, Alabama Following Christ © 2017 by Nathan E. Brown COMEAFTERME.COM Birmingham, Alabama. All rights reserved. Cover design by Shane Muir. All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version® (ESV®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good New Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked NIV are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version,® (NIV®). Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica, Inc.TM Use by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide, www.zondervan.com. Scripture quotations marked NASB are taken from the New American Standard Bible. Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Scripture quotations marked NET are taken from the NET Bible® copyright © 1996–2005 by Biblical Studies Press, L.L.C. http://www.bible.org. Scripture quoted by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked KJV are taken from the King James Version. Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois 60189. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked NKJV are taken from the New King James Version.® Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked HCSB®, are taken from the Holman Christian Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2009 by Holman Bible Publishers. Used by permission. HCSB® is a federally registered trademark of Holman Bible Publishers. Scripture quotations marked MSG are taken from The Message (paraphrase). -

GOV 208: Mass Media in American Politics

GOV 208: Mass Media in American Politics Spring 2007 Adams 208 Instructor: Michael Franz Email: [email protected] Phone: 207-798-4318 (office) Office: 203 Hubbard Hall Office Hours: Tuesday, 10am-12pm Thursday, 2:30pm-4:30pm And by appointment This course examines the role of the mass media in American politics. The course is split into three sections. First , we consider the media as an institution, as the “fourth branch” of government. We ask, what is news? Who is a journalist? How has the media changed over the course of American political development, and specifically with the rise of the Internet? Second , we consider the media in action— that is, how journalists cover the news. Is the media biased? How would (do) you know? What is the relationship between the media and government? How do the media frame the events they cover? Finally , we investigate media effects. What are the effects of media coverage on citizens—more specifically on citizens’ trust in government and political behavior? How do citizens respond to the nature of news coverage? Throughout the course we will spend considerable time considering the impact of different media forms—for example, blogging, talk radio, and entertainment media. Course Requirements There are six major components to your grade: 1. Five reading reactions (15 points; each worth 3 points)—these are short reactions of about 2 pages (double-spaced). I will evaluate these on the basis of how well you react to the readings (namely, originality of thought and conciseness). There are no right or wrong answers, but I will challenge you to think logically. -

Content and Programming Copyright 2004 MSNBC

Content and programming copyright 2004 MSNBC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Transcription Copyright 2004 FDCH e-Media (f/k/a/ Federal Document Clearing House, Inc.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. MSNBC SHOW: SCARBOROUGH COUNTRY 22:00 May 25, 2004 Tuesday TRANSCRIPT: # 052500cb.471 SECTION: NEWS; INTERNATIONAL LENGTH: 7717 words HEADLINE: SCARBOROUGH COUNTRY For May 25, 2004 BYLINE: Dana Kennedy; Joe Scarborough GUESTS: Lloyd Grove; Ana Marie Cox; Chaunce Hayden; Drew Pinsky; Megan Stecher; Michelle Stecher; Myron Ebell; Jack Burkman; Eric Alterman; Robert F. Kennedy Jr. [...] SCARBOROUGH: As Al Franken once said on "Saturday Night Live," the world comes to end. Details at 6:00. Well, that's what they say happens in "The Day After Tomorrow" movie. We're going to be talking to Robert Kennedy about that in just a second. (COMMERCIAL BREAK) SCARBOROUGH: Is Hollywood using its summer blockbusters to sway the next presidential election? Well, this Friday, "The Day After Tomorrow" opens. It's a $125 million movie that portrays a worldwide natural disaster that is brought on by global warning. MoveOn.org and Al Gore are even promoting what some are calling a presidential hit piece. Well, we've got Robert F. Kennedy Jr. He's the senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council and president of the Waterkeeper Alliance. We also have Dana Kennedy, no relation, I don't think, NBC entertainment editor. And Myron Ebell, he's the director of global warning policy for the Competitive Enterprise Institute. Dana Kennedy, let's go to you. First Michael Moore at Cannes and now this movie. Is Hollywood going to actually take votes from George Bush this fall with these movies? DANA KENNEDY, NBC ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR: If I had to vote right now about these two movies—I haven't seen Michael Moore's documentary. -

Download Appendix A

APPENDIX A News Coverage of Immigration 2007: A political story, not an issue, covered episodically—Content Methodology “News Coverage of Immigration 2007: A political story, not an issue, covered episodically” is a report based on additional analysis of content already aggregated in PEJ’s weekly News Coverage Index (NCI). The NCI examines 48 news outlets in real time to determine what is being covered and what is not. The complete methodology of the weekly NCI can be found at http://www.journalism.org/about_news_index/methodology. The findings are then released in a weekly NCI report. All coding is conducted in-house by PEJ’s staff of researchers continuous throughout the year. Examining the news agenda of 48 different outlets in five media sectors, including newspapers, online, network TV, cable TV and radio, the NCI is designed to provide news consumers, journalists, and researchers with hard data about what stories and topics the media are covering, the trajectories of major stories and differences among news platforms. This report focused primarily on stories on immigration within the Index. For this report, all stories that had been already coded as being on immigration were isolated and further analyzed to locate the presence of immigration over a year’s worth of news, and how immigration coverage ebbed and flowed throughout 2007. This provided us with the answers to questions, such as which aspects of the immigration issue did the media most tune into?; what was not covered?; and who provided the most coverage? The data for this analysis came from a year’s worth of content analysis conducted by PEJ for the NCI. -

Chronology of Outlets Coded for the Weekly News Index

Project for Excellence in Journalism Weekly News Index Updated 1/9/12 Chronology of Outlets We code the front page of newspapers for our sample. 1. Newspapers First Tier Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday; 1 every Sunday (January 1, 2011-present) Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2010-December 31, 2010) January 1, 2010 – present The New York Times Los Angeles Times USA Today Wall Street Journal Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2007-December 31, 2009) January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009 The Washington Post Los Angeles Times USA Today The Wall Street Journal Code every day except Saturday (January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009) The New York Times Second Tier Code 2 out of 4 every weekday; 1 every Sunday (January 1, 2011-present) Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2007-December 31, 2010) January 1, 2010 – present The Washington Post (was Tier 1 from January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009) January 1, 2012 – present The Denver Post Houston Chronicle Orlando Sentinel 1 January 1, 2011 – December 31, 2011 Toledo Blade The Arizona Republic Atlanta Journal Constitution January 1, 2010 – December 31, 2010 Columbus Dispatch Tampa Tribune Seattle Times January 1, 2009-December 31, 2009 Kansas City Star Pittsburgh Post-Gazette San Antonio Express-News San Jose Mercury News March 31, 2008- December 31, 2008 The Philadelphia Inquirer Chicago Tribune Arkansas Democrat-Gazette San Francisco Chronicle January 1, 2007-March 30, 2008 The Boston Globe Star Tribune Austin American-Statesman Albuquerque Journal Third Tier Rotate between 1 out of 3 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2011 – present) January 1, 2012– present Traverse City Record-Eagle (MI) The Daily Herald (WA) The Eagle-Tribune (MA) January 1, 2011 – December 31, 2011 The Hour St. -

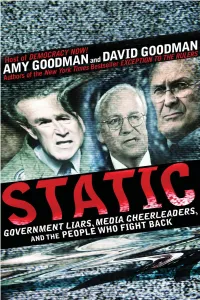

STATIC Also by Amy Goodman and David Goodman

STATIC Also by Amy Goodman and David Goodman The Exception to the Rulers: Exposing Oily Politicians, War Profiteers, and the Media That Love Them Amy Goodman and David Goodman STATIC Government Liars, Media Cheerleaders, and the People Who Fight Back New York Excerpt from Gedichte, Vol. 4, by Bertolt Brecht, copyright 1961 Suhrkamp Verlag, reprinted by permission of Suhrkamp Verlag. Excerpt from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” reprinted by arrangement with the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr, c/o Writers House as agent for the proprietor, New York, NY. Copyright 1963 Martin Luther King, Jr., copyright renewed 1991 Coretta Scott King. “Be Nobody’s Darling,” by Alice Walker, reprinted by permission of the author. Excerpt of “Instant-Mix Imperial Democracy,” by Arundhati Roy, reprinted by permis- sion of the author. Parts of Chapter 14, “Anti-Warriors,” originally appeared in the article “Breaking Ranks,” by David Goodman, Mother Jones, November/December 2004. Copyright © 2006 Amy Goodman and David Goodman Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 1-4013-8610-5 1. United States—Politics and government—2001– . 2. United States—Foreign relations—2001– . 3. Mass media—Political aspects—United States. 4. Political activists—United States. I. Goodman, David. II. Title. first eBook edition To our late grandparents, Benjamin and Sonia Bock Solomon and Gertrude Goodman Immigrants all Who fled persecution seeking a kinder, more just world Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Unembedded 1 SECTION I: LIARS AND CHEERLEADERS 1 : Outlaw Nation 17 2 : Watching You 46 3 : News Fakers 62 4 : Unreality TV 73 5 : The Mighty Wurlitzer 90 6 : Hijacking Public Media 100 7 : Whitewashing Haiti 113 8 : Witch Hunt 132 9 : The Torturers’ Apprentice 149 10 : Exporting Abuse 168 11 : Unembedded in Fallujah 189 12 : Oil Profiteers 199 SECTION II: FIGHTING BACK 13 : Cindy’s Crawford 209 14 : Anti-Warriors 222 15 : Human Wrongs 244 viii CONTENTS 16 : Bravo Bush! 257 17 : We Interrupt This Program . -

TOWN of RYE – PLANNING BOARD MEETING Tuesday, December 8, 2020 6:00 P.M

DRAFT MINUTES of the PB Meeting 12-02-20 TOWN OF RYE – PLANNING BOARD MEETING Tuesday, December 8, 2020 6:00 p.m. – via ZOOM Members Present: Chair Patricia Losik, Vice-Chair JM Lord, Steve Carter, Katy Sherman, Jim Finn, Nicole Paul, Selectmen’s Rep Bill Epperson, and Alternates Jeffrey Quinn and Bill MacLeod Others Present for the Town: Planning/Zoning Administrator Kim Reed and Attorney Michael Donovan (joined meeting at 6:30 p.m.) Call to Order Chair Losik called the meeting to order via Zoom teleconferencing at 6:00 p.m. Statement by Patricia Losik: As chair of the Rye Planning Board, I find that due to the State of Emergency declared by the Governor as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and in accordance with the Governor’s Emergency Order #12 pursuant to Executive Order 2020-04, this public body is authorized to meet electronically. Please note that there is no physical location to observe and listen contemporaneously to this meeting, which was authorized pursuant to the Governor’s Emergency Order. However, in accordance with the Emergency Order, I am confirming that we are providing public access to the meeting by telephone, with additional access possibilities by video and other electronic means. We are utilizing Zoom for this electronic meeting. All members of the board have the ability to communicate contemporaneously during this meeting through this platform, and the public has access to contemporaneously listen and, if necessary, participate in this meeting by clicking on the following website address: www.zoom.com ID #835-9967-0907 Password: 123456 Public notice has been provided to the public for the necessary information for accessing the meeting, including how to access the meeting using Zoom telephonically. -

527S in a Post-Swift Boat Era: the Urc Rent and Future Role of Issue Advocacy Groups in Presidential Elections Lauren Daniel

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 6 Spring 2010 527s in a Post-Swift Boat Era: The urC rent and Future Role of Issue Advocacy Groups in Presidential Elections Lauren Daniel Recommended Citation Lauren Daniel, 527s in a Post-Swift Boat Era: The Current and Future Role of Issue Advocacy Groups in Presidential Elections, 5 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 149 (2010). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol5/iss1/6 This Note or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2010 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 5 (Spring 2010) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy 527s in a Post-Swift Boat Era: The Current and Future Role of Issue Advocacy Groups in Presidential Elections Lauren Daniel* I. INTRODUCTION We resent very deeply the false war crimes charges [Senator John Kerry] made coming back from Vietnam [in 1971 and repeated in the book Tour of Duty.] [W]e think those have cast aspersion on [American veterans] both living and dead. We think that they are unsupportable. We intend to bring the truth to the American people. We believe that based on our experience with him, he is totally unfit to be commander in chief.1 ¶1 In 2004, U.S. Senator John Kerry was defeated by incumbent George W. Bush in the race for the United States presidency by a margin of less than 2.5% of the popular vote.2 Political pundits have offered numerous explanations for Kerry’s defeat: his alleged flip-flopping on the Iraq War, his perceived lofty New England intellectualism, and his reported lack of appeal to the influential Evangelical Christians on morality issues.3 One of the most widely recognized reasons for Kerry’s 2004 loss, however, credits the involvement of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth (Swift Boaters).