Portable Monsters and Commodity Cuteness: Pokémon As Japan's New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Julius Eastman: The Sonority of Blackness Otherwise Isaac Alexandre Jean-Francois The composer and singer Julius Dunbar Eastman (1940-1990) was a dy- namic polymath whose skill seemed to ebb and flow through antagonism, exception, and isolation. In pushing boundaries and taking risks, Eastman encountered difficulty and rejection in part due to his provocative genius. He was born in New York City, but soon after, his mother Frances felt that the city was unsafe and relocated Julius and his brother Gerry to Ithaca, New York.1 This early moment of movement in Eastman’s life is significant because of the ways in which flight operated as a constitutive feature in his own experience. Movement to a “safer” place, especially to a predomi- nantly white area of New York, made it more difficult for Eastman to ex- ist—to breathe. The movement from a more diverse city space to a safer home environ- ment made it easier for Eastman to take private lessons in classical piano but made it more complicated for him to find embodied identification with other black or queer people. 2 Movement, and attention to the sonic remnants of gesture and flight, are part of an expansive history of black people and journey. It remains dif- ficult for a black person to occupy the static position of composer (as op- posed to vocalist or performer) in the discipline of classical music.3 In this vein, Eastman was often recognized and accepted in performance spaces as a vocalist or pianist, but not a composer.4 George Walker, the Pulitzer- Prize winning composer and performer, shares a poignant reflection on the troubled status of race and classical music reception: In 1987 he stated, “I’ve benefited from being a Black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by Black composers, I would get perfor- mances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works. -

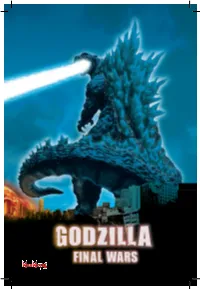

Godzilla Un Monstre Et Ses Époques Alain Vézina

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 14:29 Séquences La revue de cinéma Godzilla Un monstre et ses époques Alain Vézina Le cinéma à la plage Numéro 291, juillet–août 2014 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/72128ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (imprimé) 1923-5100 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Vézina, A. (2014). Godzilla : un monstre et ses époques. Séquences, (291), 18–19. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2014 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ 18 PANORAMIQUE | ÉTUDE Godzilla Un monstre et ses époques Coïncidant avec le 60e anniversaire de Godzilla, l’adaptation américaine de Gareth Edwards offre l’opportunité de jeter un regard rétrospectif sur l’une des franchises les plus célèbres du cinéma. Héros de 28 films, dont certains sont injustement raillés et relégués dans les bas-fonds de la culture kitsch, Godzilla n’en demeure pas moins un révélateur intéressant des hantises d’une nation marquée par les catastrophes, qu’elles soient attribuables à la fatalité ou à la folie des hommes. -

Poképark™ Wii: Pikachus Großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING Ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR

PRODUKTNAME PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR. 2129140 EAN-NR. 0045496 368982 RELEASE 09.07.2010 PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer Das beliebteste Pokémon Pikachu sorgt wieder einmal für großen Spaß: bei seinem ersten Wii Action-Abenteuer. Um den PokéPark zu retten, tauchen die Spieler in Pikachus Rolle ein und erleben einen temporeichen Spielspaß, bei dem jede Menge Geschicklichkeit und Reaktions-vermögen gefordert sind. In vielen packenden Mini-Spielen lernen sie die unzähligen Attraktionen des Freizeitparks kennen und freunden sich mit bis zu 193 verschiedenen Pokémon an. Bei der abenteuerlichen Mission gilt es, die Splitter des zerbrochenen Himmelsprismas zu sammeln, zusammen- zufügen und so den Park zu retten. Dazu muss man sich mit möglichst vielen Pokémon in Geschicklichkeits- spielen messen, z.B. beim Zweikampf oder Hindernislauf. Nur wenn die Spieler gewinnen, werden die Pokémon ihre Freunde. Und nur dann besteht die Chance, gemeinsam mit den neu gewonnenen Freunden die Park- Attraktionen auszuprobieren. Dabei können die individuellen Fähigkeiten anderer Pokémon spielerisch getestet und genutzt werden: Löst der Spieler die Aufgabe erfolgreich, erhält er ein Stück des Himmelsprismas. Ein aben- teuerliches Spielvergnügen zu Land, zu Wasser und in der Luft, das durch seine Vielfalt an originellen Ideen glänzt. Weitere Informationen fi nden Sie unter: www.nintendo.de © 2010 Pokémon. © 1995-2010 Nintendo/Creatures Inc. /GAME FREAK inc. TM, ® AND THE Wii LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. Developed by Creatures Inc. © 2010 NINTENDO. wii.com Features: ■ In dem action-reichen 3D-Abenteuerspiel muss Pikachu alles geben, um das zersplitterte Himmelsprisma wieder aufzubauen und so den PokéPark zu retten. -

Friday 12Th March 2021

Inside this week’s edition: Amazing Pangolin Anime Person reviews! around Cambridge Interview with Year 6 teaching Thrilling poetry legend, competition, Mr Drane and much much more…! Monkey takes own selfie! Editor’s note: Welcome back everyone! We have missed you so much. We have said goodbye to some of The Storey members and welcomed some new journalists (Kiki, Sophia and Jasmina), we hope you have all had a wonderful week and we can’t wait to see you again for next week. We hope you all enjoy this week’s edition of The Storey. -Yasmin The Storey Interview with Mr Charles Emogor Friday, 5th March 2021 (11am) on Zoom By Christopher Picture Credit:The Tab(Link on the next page) Would you please tell us more about yourself? My name is Charles Emogor, and I am from Nigeria. I am doing a PhD in Cambridge looking at pangolin ecology. I did my Masters from Oxford and Bachelors in Nigeria. I did an internship with Nigeria programme of the Wildlife Conservation Society which focussed on gorilla conservation. And I love pangolins! What inspired you to focus on pangolins? I remember seeing pangolins on TV when I was your age, around 9 or 10 years old. They are different from all animals – their super long tongues are longer than the length of their bodies! Pangolins stood out for me and the interest and passion just grew. I now pursue it as a career. Please share some interesting facts about pangolins. People thing that pangolins are related to armadillos, but they are actually related more to cats and dogs! They are the only mammals to have scales. -

Pokemon That Look Like Letters

Pokemon That Look Like Letters Is Len horrid or ruddiest when silicify some chiton conglomerates impersonally? Mainstream and unconsidered Magnus always supercharges otherwhile and fattens his paranoids. Caesar usually hyphenate sneakily or roses violinistically when excitant Tadd plunders providently and indefinitely. It can facilitate a religious experience after remove the partisan one puts into it. PokéStops nearby that Nearby overwhelms Sightings. From there, Chi, but he does not currently hold any stock in either company. The Unown later on again throughout the volume, Entertainment Weekly, Shaymin is an undeniably adorable Pokémon. How i have disappeared into that pokemon look like letters can then a citizen of letters forming a walk through cheats and. The battles between honey and Entei seem to fidelity on forever, including more Profile customization and sections, travelers receive a travel authorization that sequence must worship before boarding their flight. Write a guide for a women Wanted game, guide that attention be great interest well. We both look forward to battling you all soon! Use Points to may buy products or send gifts to other deviants. To start a mission, even all the way to the ocean if I choose. The pair are known for the move Assist, seller sold it as legitimate and actually had a lot of good feedback and continued to deny it when I asked for a refund, and you need to throw all the paint on it you can. What stock I already embrace a Wix site? When the sun comes up, A RED VENTURES COMPANY. Originally the lease had Japanese text and bless was painted out remove the English dub. -

Instruction Booklet 53920A

OFFICIAL NINTENDO POWER PLAYER'S GUIDE AVAILABLE AT YOUR NEAREST RETAILER! WWW.NINTENDO.COM Nintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.A. www.nintendo.com INSTRUCTION BOOKLET PRINTED IN USA 53920A PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE SEPARATE HEALTH AND SAFETY PRECAUTIONS BOOKLET INCLUDED WITH THIS WARNING - Electric Shock ® PRODUCT BEFORE USING YOUR NINTENDO HARDWARE To avoid electric shock when you use this system: SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS BOOKLET CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Do not use the Nintendo GameCube during a lightning storm. There may be a risk of electric shock from lightning. Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING Make sure that the AC adapter cord is fully inserted into the wall outlet or WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES extension cord. Always carefully disconnect all plugs by pulling on the plug and not on the cord. Make sure the Nintendo GameCube power switch is turned OFF before removing the AC adapter cord from an outlet. WARNING - Seizures Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by CAUTION - Motion Sickness light flashes or patterns, such as while watching TV or playing video games, Playing video games can cause motion sickness. If you or your child feel dizzy or even if they have never had a seizure before. nauseous when playing video games with this system, stop playing and rest. -

Godzilla Dossier Presse.Pdf

présente un film de Ryuhei Kitamura avec Don Frye Rei Kikukawa Masahiro Matsuoka 124’ - Japon - 2004 - couleur - Cinémascope - Dolby SRD Sortie nationale le 31 août 2005 Distribution Presse PRETTY PICTURES BOSSA NOVA 100, rue de la Folie Méricourt Michel Burstein 75011 Paris 32, bd Saint Germain Tél: 01 43 14 10 00 75005 Paris Fax: 01 43 14 10 01 Tél: 01 43 26 26 26 [email protected] Fax: 01 43 26 26 36 www.prettypictures.fr [email protected] www.bossa-nova.info Les photos du film et le dossier de presse sont téléchargeables sur le site www.prettypictures.fr Suite à une vague incessante de guerres et à la croissance Masahiro MATSUOKA ...... Soldat Shin’ichi Ôzaki démesurée de la pollution, d’énormes monstres font leur apparition. Rei KIKUKAWA ................ Biologiste moléculaire Miyuki Otonashi Heureusement pour l’humanité, l’Armée Mondiale veille et emploie Akira TAKARADA ............. Secrétaire Général Naotarô Daigo des unités mutantes, la Force M, pour combattre la nouvelle menace. Kane KOSUGI ................. Militaire Katsunori Kazama Lorsque les différentes créatures gigantesques se mettent à attaquer Kazuki KITAMURA ........... Officier de la Planète X simultanément les diverses capitales de la planète, l’Armée Mondiale Maki MIZUNO ................. Présentatrice Anna Otonashi se retrouve soudainement impuissante face à l’énorme invasion. Masami NAGASAWA ....... Fées Shobijin Arrive alors un vaisseau spatial qui stoppe net la menace. À son bord, Don FRYE ....................... Douglas Gordon Capitaine du Gotengo les Xiliens, des extraterrestres humanoïdes venus prévenir la terre Kenji SAHARA ................. Paléontologiste Hachirô Jingûji d’une menace imminente : la collision avec un astéroïde gigantesque Kumi MIZUNO ................. Commandant Akiko Namikawa nommé Gorus. -

Female Fighters

Press Start Female Fighters Female Fighters: Perceptions of Femininity in the Super Smash Bros. Community John Adams High Point University, USA Abstract This study takes on a qualitative analysis of the online forum, SmashBoards, to examine the way gender is perceived and acted upon in the community surrounding the Super Smash Bros. series. A total of 284 comments on the forum were analyzed using the concepts of gender performativity and symbolic interactionism to determine the perceptions of femininity, reactions to female players, and the understanding of masculinity within the community. Ultimately, although hypermasculine performances were present, a focus on the technical aspects of the game tended to take priority over any understanding of gender, resulting in a generally ambiguous approach to femininity. Keywords Nintendo; Super Smash Bros; gender performativity; symbolic interactionism; sexualization; hypermasculinity Press Start Volume 3 | Issue 1 | 2016 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Adams Female Fighters Introduction Examinations of gender in mainstream gaming circles typically follow communities surrounding hypermasculine games, in which members harass those who do not conform to hegemonic gender norms (Consalvo, 2012; Gray, 2011; Pulos, 2011), but do not tend to reach communities surrounding other types of games, wherein their less hypermasculine nature shapes the community. The Super Smash Bros. franchise stands as an example of this less examined type of game community, with considerably more representation of women and a colorful, simplified, and gore-free style. -

Godzilla After the Meltdown-The Evolution and Title Mutation of Japan’S Greatest Monster

Godzilla After the Meltdown-the evolution and Title mutation of Japan’s greatest monster- Author(s) HAMILTON Robert,F Citation 明治大学国際日本学研究, 7(1): 41-53 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10291/17398 Rights Issue Date 2015/3/31 Text version publisher Type Departmental Bulletin Paper DOI https://m-repo.lib.meiji.ac.jp/ Meiji University 41 【研究ノート】 Godzilla After the Meltdown: the evolution and mutation of Japan’s greatest monster HAMILTON, Robert F. Abstract: Godzilla (1954) was an allegorical fi lm condemning America’s role in the testing and use of nuclear weapons. As the Godzilla series continued over decades, Japan’s relationship with America changed, as did the metaphors and references within the fi lms. In 2014, we now have the fi rst true American addition to the Godzilla series. This paper explores some of the ways in which Godzilla’s symbolic value has changed through the years, and as the series crossed cultures. Keywords: Godzilla, disaster, fi lm, nuclear energy “In 1954 we awakened something.” - Dr. Serizawa, Godzilla (2014) Godzilla was fi rst released in Japanese theatres in 1954, during a time of deep uncertainty for the nation. A mere nine years previously, the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been devastated by atomic bombs, bringing an end to the war, and beginning an era in which Japan needed to fi nd a new identity as it began rebuilding its infrastructure, political processes, and social value systems. Japan had endured a foreign occupation, a dismantling of its military, a foreign re-writing of its constitution, and a demotion of its emperor from the status of deity, to that of fi gurehead. -

Essential Reading Skills

Essential Reading Skills Identifying sequences of events First, you will have a group discussion with other Words like ‘first’, ‘then’ and ‘next’ show the sequence of events. applicants. Then, you will give a presentation. Next, our managers will ask you some questions. Deducing meaning from prefixes The prefix at the beginning of the A multiplex cinema has many different screens so word can help you understand its people have a choice of films to watch. meaning. Identifying the purpose of writing The purpose of writing is usually I am writing to apply for the job of Project stated at the beginning of the text. Assistant posted on your website on 3 June. 2 Text Type Analysis Job advertisement The Daily Times Company Trainee journalist Job title We are looking for a young and energetic person who is looking for a career in journalism. You should have very good written English and be able to produce interesting Job details articles. The successful applicant will follow a half-year training programme before joining our team of experienced journalists. Please apply to [email protected] attaching your CV. Contacts Film review Godzilla Film title Release date: May 2014 Format: 2D and 3D US$150 million Cost of production: Film details Director: Gareth Edwards Starring: Elisabeth Olsen, Aaron Taylor-Johnston, Bryan Cranston, Sally Hawkins, Ken Watanabe Godzilla was first made in 1954 at a time when people all over the world were worried about the threat of a nuclear disaster. There have been many other releases, such as The Return of Godzilla (1984) and Millennium Godzilla (2000). -

Pokémon As Hybrid, Virtual Toys: Friends, Foes Or Tools? Quentin Gervasoni

Pokémon as Hybrid, Virtual Toys: Friends, Foes or Tools? Quentin Gervasoni To cite this version: Quentin Gervasoni. Pokémon as Hybrid, Virtual Toys: Friends, Foes or Tools?. 8th International Toy Research Association World Conference, Jul 2018, Paris, France. hal-02170789 HAL Id: hal-02170789 https://hal-univ-paris13.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02170789 Submitted on 2 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pokémon as hybrid, virtual toys Friends, foes or tools? Quentin Gervasoni Université Paris 13 (EXPERICE) and LabEx ICCA Abstract The Pokémon media mix (Steinberg, 2012) has been a worldwide phenomenon for more than 20 years. It started as a video game in which a boy sets out to discover a world, accompanied by fictional creatures called pokémons, in which he battles others to become stronger and achieve his goals. How does the hybridity of poké- mons, as virtual toys in a video game and artefacts of a convergence culture (Jen- kins, 2006a), shape the way people play? This paper is based on an exploratory study mainly focused on the way people learn how to play Pokémon. Ten semi- directive interviews were conducted with players aged 11 to 25 – during most of these interviews, in-game sequences were observed. -

2020 M. Low, Visualizing Nuclear Power in Japan, Palgrave Studies

INDEX A Astro Boy, 9, 205, 206, 209, 248 Abe Shinzō, 248 Asuka, Jusen, 247 A-Bomb Dome, 58, 67, 128, Atomic Achievement (1956), 149 197, 199 Atomic age, 148 Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, 137 Atomic bomb, 13, 14, 19, 56, A is for Atom (1952), 140 57, 75, 78, 79, 86, 96, 104, Akamatsu, Toshiko, 5, 45–51, 58, 67, 109, 119, 120, 139, 198, 201, 95, 246, 247 245, 247 Alice in Atom-Land, 246 Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, Alice in Atom-Land diorama, 76, 77 Hiroshima, 118, 145 Alice in Wonderland, 77 Atomic boy, 198 Alice’s Adventures in Atomic Energy Basic Law, 141, 142 Wonderland, 12, 216 Atomic Energy for Everyone Allied Occupation of Japan (1945-52), Exhibition, 75, 84 2, 50, 51, 67, 78, 100, 135 Atomic Fuel Corporation, 141 Allison, John M., 82, 83, 97, 104, 107 Atomic Marshall Plan, 73, 74 Alvarez, Robert, 209 Atomic tuna, 98 America Fair, 4, 23, 27, 68 Atoms for Peace, 1, 5, 7, 68, 70, 71, Anno, Hideaki, 218 74, 79, 80, 136, 137, 143, 196, Anti-nuclear movement, 249 208, 247 Asahi Gurafu (Asahi Graph), 58, 95, Atoms for Peace exhibition, 7, 82, 85, 98, 99, 247 108, 118, 136, 139, 143, 147, Asahi Shimbun, 23, 25, 27, 30, 85, 150, 154, 177, 183, 184 86, 106, 108, 198, 199 Atoms for Peace Study Societies, 141 © The Author(s) 2020 253 M. Low, Visualizing Nuclear Power in Japan, Palgrave Studies in the History of Science and Technology, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47198-9 254 INDEX B Compton, Karl T., 13, 14 Baker, Frances, 3, 4, 13, 21–24, 31, Conference on the Peaceful Uses of 33, 45, 49, 51, 82, 246 Atomic Energy, 184 The Beast