Female Fighters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hyrule Warriors™ Es Un Juego De Acción Táctica Ambientado En El Universo De the Legend of Zelda™

Hyrule Warriors 1 Infor maci ón impo rtan te Cgonfi urnació 2 Coontr les y acce sori os 3 Func ion es en lín ea 4 Aviso para padres o tuto res Inicio 5 Acerca del jue go 6 Comenz ar a jug ar 7 Guar dar la parti da Comenzar la aventura 8 Selec ción de escenar io 9 Contro les básic os 10 Cont rol es de a taq ue WUP-P-BWPE-02 11 Pant all a prin cip al 12 Baat lsla 13 Bastion es y puestos de avanz ada 14 Anfieidead sl e emtn asled ya h biil dase 15 Ojtb ecoos enotan r dse ne l cmoa p de batlaal Hace rse más f uer te 16 Sidub r eil n ve 17 Aument ar la sal ud 18 Tnraiisrfe ra h bil deadtmsn e rae rsa 19 Caire r nsnsig ia 20 Caere r liix re s El mod o Aventu ra 21 Sobre el modo Av entu ra 22 Pantal la del ma pa 23 Bqús uesda 24 Lkvin s irastu le Cont eni do adic ion al 25 Contenido a dicional (de pa go) Acerc a de este pr oduc to 26 Asvi os laseg le Solución de problem as 27 Informaci ón de asisten cia 1 Infor maci ón impo rtan te Información importante Lee detenidamente este manual antes de usar este programa. Si un niño va a utilizar este programa, un adulto debe leerle y explicarle el contenido de este manual. Además, antes de usar este programa asegúrate de leer el contenido de la aplicación Información sobre salud y seguridad ( ) a la que puedes acceder desde el menú de Wii U. -

Princess Peach Bowser Luigi

English Answers for the lesson on Wednesday, 15 July 2020 2 Profiles (answers) You are not expected to identify every example! Nouns Verbs Adjectives Adverbs Princess Peach Princess Peach has long, blonde hair and blue eyes. She is tall and usually wears a pink evening gown with frilly trimmings. Her hair is sometimes pulled back into a high ponytail. Peach is mostly kind and does not show an aggressive nature, even when she is fearlessly fighting or confronting her enemies. Although often kidnapped by huge Bowser, Peach is always happy to have Bowser on the team when a bigger evil threatens the Mushroom Kingdom. She puts previous disagreements aside. Bowser Bowser is the King of the Koopas. Koopas are active turtles that live in the Mushroom Kingdom. Bowser has a large, spiked turtle shell, horns, razor-sharp fangs, clawed fingers and toes, and bright red hair. He is hugely strong and regularly breathes fire. Bowser can also jump high. He often kidnaps Princess Peach to lure poor Mario into a trap. Bowser occasionally works with Mario and Luigi to defeat a greater evil. Then they work together. Luigi Luigi is taller than his older brother, Mario, and is usually dressed in a green shirt with dark blue overalls. Luigi is an Italian plumber, just like his brother. He always seems nervous and timid but is good-natured. He is calmer than his famous brother. If there is conflict, Luigi will smile and walk away. It is often thought that Luigi may secretly love Princess Daisy. . -

An Exploration of Zombie Narratives and Unit Operations Of

Acta Ludologica 2018, Vol. 1, No. 1 ABSTRACT: This document details the abstract for a study on zombie narratives and zombies as units and their translation from cinemas to interactive mediums. Focusing on modern zombie mythos and aesthetics as major infuences in pop-culture; including videogames. The main goal of this study is to examine the applications The Infectious Aesthetic of zombie units that have their narrative roots in traditional; non-ergodic media, in videogames; how they are applied, what are their patterns, and the allure of Zombies: An Exploration of their pervasiveness. of Zombie Narratives and Unit KEY WORDS: Operations of Zombies case studies, cinema, narrative, Romero, unit operations, videogames, zombie. in Videogames “Zombies to me don’t represent anything in particular. They are a global disaster that people don’t know how to deal with. David Melhart, Haryo Pambuko Jiwandono Because we don’t know how to deal with any of the shit.” Romero, A. George David Melhart, MA University of Malta Institute of Digital Games Introduction 2080 Msida MSD Zombies are one of the more pervasive tropes of modern pop-culture. In this paper, Malta we ask the question why the zombie narrative is so infectious (pun intended) that it was [email protected] able to successfully transition from folklore to cinema to videogames. However, we wish to look beyond simple appearances and investigate the mechanisms of zombie narratives. To David Melhart, MA is a Research Support Ofcer and PhD student at the Institute of Digital do this, we employ Unit Operations, a unique framework, developed by Ian Bogost1 for the Games (IDG), University of Malta. -

NEW SUPER MARIO BROS.™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ Systems

NTR-A2DP-UKV INSTRUCTIONINSTRUCTION BOOKLETBOOKLET (CONTAINS(CONTAINS IMPORTANTIMPORTANT HEALTHHEALTH ANDAND SAFETYSAFETY INFORMATION)INFORMATION) [0610/UKV/NTR] WIRELESS DS SINGLE-CARD DOWNLOAD PLAY THIS GAME ALLOWS WIRELESS MULTIPLAYER GAMES DOWNLOADED FROM ONE GAME CARD. This seal is your assurance that Nintendo 2–4 has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence WIRELESS DS MULTI-CARD PLAY in workmanship, reliability and THIS GAME ALLOWS WIRELESS MULTIPLAYER GAMES WITH EACH NINTENDO DS SYSTEM CONTAINING A entertainment value. Always look SEPARATE GAME CARD. for this seal when buying games and 2–4 accessories to ensure complete com- patibility with your Nintendo Product. Thank you for selecting the NEW SUPER MARIO BROS.™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ systems. IMPORTANT: Please carefully read the important health and safety information included in this booklet before using your Nintendo DS system, Game Card, Game Pak or accessory. Please read this Instruction Booklet thoroughly to ensure maximum enjoyment of your new game. Important warranty and hotline information can be found in the separate Age Rating, Software Warranty and Contact Information Leaflet. Always save these documents for future reference. This Game Card will work only with Nintendo DS systems. IMPORTANT: The use of an unlawful device with your Nintendo DS system may render this game unplayable. © 2006 NINTENDO. ALL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE COPYRIGHTS OF GAME, SCENARIO, MUSIC AND PROGRAM, RESERVED BY NINTENDO. TM, ® AND THE NINTENDO DS LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. © 2006 NINTENDO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This product uses the LC Font by Sharp Corporation, except some characters. LCFONT, LC Font and the LC logo mark are trademarks of Sharp Corporation. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2013 (Briefing Date: 1/30/2014) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Dec.'09 Apr.-Dec.'10 Apr.-Dec.'11 Apr.-Dec.'12 Apr.-Dec.'13 Net sales 1,182,177 807,990 556,166 543,033 499,120 Cost of sales 715,575 487,575 425,064 415,781 349,825 Gross profit 466,602 320,415 131,101 127,251 149,294 (Gross profit ratio) (39.5%) (39.7%) (23.6%) (23.4%) (29.9%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 169,945 161,619 147,509 133,108 150,873 Operating income 296,656 158,795 -16,408 -5,857 -1,578 (Operating income ratio) (25.1%) (19.7%) (-3.0%) (-1.1%) (-0.3%) Non-operating income 19,918 7,327 7,369 29,602 57,570 (of which foreign exchange gains) (9,996) ( - ) ( - ) (22,225) (48,122) Non-operating expenses 2,064 85,635 56,988 989 425 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) (84,403) (53,725) ( - ) ( - ) Ordinary income 314,511 80,488 -66,027 22,756 55,566 (Ordinary income ratio) (26.6%) (10.0%) (-11.9%) (4.2%) (11.1%) Extraordinary income 4,310 115 49 - 1,422 Extraordinary loss 2,284 33 72 402 53 Income before income taxes and minority interests 316,537 80,569 -66,051 22,354 56,936 Income taxes 124,063 31,019 -17,674 7,743 46,743 Income before minority interests - 49,550 -48,376 14,610 10,192 Minority interests in income -127 -7 -25 64 -3 Net income 192,601 49,557 -48,351 14,545 10,195 (Net income ratio) (16.3%) (6.1%) (-8.7%) (2.7%) (2.0%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Julius Eastman: The Sonority of Blackness Otherwise Isaac Alexandre Jean-Francois The composer and singer Julius Dunbar Eastman (1940-1990) was a dy- namic polymath whose skill seemed to ebb and flow through antagonism, exception, and isolation. In pushing boundaries and taking risks, Eastman encountered difficulty and rejection in part due to his provocative genius. He was born in New York City, but soon after, his mother Frances felt that the city was unsafe and relocated Julius and his brother Gerry to Ithaca, New York.1 This early moment of movement in Eastman’s life is significant because of the ways in which flight operated as a constitutive feature in his own experience. Movement to a “safer” place, especially to a predomi- nantly white area of New York, made it more difficult for Eastman to ex- ist—to breathe. The movement from a more diverse city space to a safer home environ- ment made it easier for Eastman to take private lessons in classical piano but made it more complicated for him to find embodied identification with other black or queer people. 2 Movement, and attention to the sonic remnants of gesture and flight, are part of an expansive history of black people and journey. It remains dif- ficult for a black person to occupy the static position of composer (as op- posed to vocalist or performer) in the discipline of classical music.3 In this vein, Eastman was often recognized and accepted in performance spaces as a vocalist or pianist, but not a composer.4 George Walker, the Pulitzer- Prize winning composer and performer, shares a poignant reflection on the troubled status of race and classical music reception: In 1987 he stated, “I’ve benefited from being a Black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by Black composers, I would get perfor- mances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works. -

Ssbu Character Checklist with Piranha Plant

Ssbu Character Checklist With Piranha Plant Loathsome Roderick trade-in trippingly while Remington always gutting his rhodonite scintillates disdainfully, he fishes so embarrassingly. Damfool and abroach Timothy mercerizes lightly and give-and-take his Lepanto maturely and syntactically. Tyson uppercut critically. S- The Best Joker's Black Costume School costume and Piranha Plant's Red. List of Super Smash Bros Ultimate glitches Super Mario Wiki. You receive a critical hit like classic mode using it can unfurl into other than optimal cqc, ssbu character checklist with piranha plant is releasing of series appear when his signature tornado spins, piranha plant on! You have put together for their staff member tells you. Only goes eight starter characters from four original Super Smash Bros will be unlocked. Have sent you should we use squirtle can throw. All whilst keeping enemies and turns pikmin pals are already unlocked characters in ssbu character checklist with piranha plant remains one already executing flashy combos and tv topics that might opt to. You win a desire against this No DLC Piranha Plant Fighters Pass 1 0. How making play Piranha Plant in SSBU Guide DashFight. The crest in one i am not unlike how do, it can switch between planes in ssbu character checklist with piranha plant dlc fighter who knows who is great. Smash Ultimate vocabulary List 2021 And whom Best Fighters 1010. Right now SSBU is the leader game compatible way this declare Other games. This extract is about Piranha Plant's appearance in Super Smash Bros Ultimate For warmth character in other contexts see Piranha Plant. -

KIRBY MASS ATTACK Shows the Percentage of the Game Completed

MAA-NTR-TADP-UKV INSTRUCTION BOOKLET (CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION) [0611/UKV/NTR] T his seal is your assurance that Nintendo has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence in workmanship, reliability and entertainment value. Always look for this seal when buying games and accessories to ensure complete com patibility with your Nintendo Product. Thank you for selecting the KIRBY™ MASS ATTACK Game Card for Nintendo DS™ systems. IMPORTANT: Please carefully read the important health and safety information included in this booklet before using your Nintendo DS system, Game Card, Game Pak or accessory. Please read this Instruction Booklet thoroughly to ensure maximum enjoyment of your new game. Important warranty and hotline information can be found in the separate Age Rating, Software Warranty and Contact Information Leafl et. Always save these documents for future reference. This Game Card will work only with Nintendo DS systems. IMPORTANT: The use of an unlawful device with your Nintendo DS system may render this game unplayable. © 2011 HAL Laboratory, Inc. / Nintendo. TM, ® and the Nintendo DS logo are trademarks of Nintendo. © 2011 Nintendo. Contents Getting Started ............................................................................................ 6 Kirby Basic Controls ................................................................................................ 8 Our hungry hero, after being split into ten by the Skull Gang boss, Necrodeus, sets out on an Making Progress ...................................................................................... -

Best Wishes to All of Dewey's Fifth Graders!

tiger times The Voice of Dewey Elementary School • Evanston, IL • Spring 2020 Best Wishes to all of Dewey’s Fifth Graders! Guess Who!? Who are these 5th Grade Tiger Times Contributors? Answers at the bottom of this page! A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R Tiger Times is published by the Third, Fourth and Fifth grade students at Dewey Elementary School in Evanston, IL. Tiger Times is funded by participation fees and the Reading and Writing Partnership of the Dewey PTA. Emily Rauh Emily R. / Levine Ryan Q. Judah Timms Timms Judah P. / Schlack Nathan O. / Wright Jonah N. / Edwards Charlie M. / Zhu Albert L. / Green Gregory K. / Simpson Tommy J. / Duarte Chaya I. / Solar Phinny H. Murillo Chiara G. / Johnson Talula F. / Mitchell Brendan E. / Levine Jojo D. / Colledge Max C. / Hunt Henry B. / Coates Eve A. KEY: ANSWER KEY: ANSWER In the News Our World............................................page 2 Creative Corner ..................................page 8 Sports .................................................page 4 Fun Pages ...........................................page 9 Science & Technology .........................page 6 our world Dewey’s first black history month celebration was held in February. Our former principal, Dr. Khelgatti joined our current Principal, Ms. Sokolowski, our students and other artists in poetry slams, drumming, dancing and enjoying delicious soul food. Spring 2020 • page 2 our world Why Potatoes are the Most Awesome Thing on the Planet By Sadie Skeaff So you know what the most awesome thing on the planet is, right????? Good, so you know that it is a potato. And I will tell you why the most awesome thing in the world is a potato, and you will listen. -

Poképark™ Wii: Pikachus Großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING Ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR

PRODUKTNAME PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR. 2129140 EAN-NR. 0045496 368982 RELEASE 09.07.2010 PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer Das beliebteste Pokémon Pikachu sorgt wieder einmal für großen Spaß: bei seinem ersten Wii Action-Abenteuer. Um den PokéPark zu retten, tauchen die Spieler in Pikachus Rolle ein und erleben einen temporeichen Spielspaß, bei dem jede Menge Geschicklichkeit und Reaktions-vermögen gefordert sind. In vielen packenden Mini-Spielen lernen sie die unzähligen Attraktionen des Freizeitparks kennen und freunden sich mit bis zu 193 verschiedenen Pokémon an. Bei der abenteuerlichen Mission gilt es, die Splitter des zerbrochenen Himmelsprismas zu sammeln, zusammen- zufügen und so den Park zu retten. Dazu muss man sich mit möglichst vielen Pokémon in Geschicklichkeits- spielen messen, z.B. beim Zweikampf oder Hindernislauf. Nur wenn die Spieler gewinnen, werden die Pokémon ihre Freunde. Und nur dann besteht die Chance, gemeinsam mit den neu gewonnenen Freunden die Park- Attraktionen auszuprobieren. Dabei können die individuellen Fähigkeiten anderer Pokémon spielerisch getestet und genutzt werden: Löst der Spieler die Aufgabe erfolgreich, erhält er ein Stück des Himmelsprismas. Ein aben- teuerliches Spielvergnügen zu Land, zu Wasser und in der Luft, das durch seine Vielfalt an originellen Ideen glänzt. Weitere Informationen fi nden Sie unter: www.nintendo.de © 2010 Pokémon. © 1995-2010 Nintendo/Creatures Inc. /GAME FREAK inc. TM, ® AND THE Wii LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. Developed by Creatures Inc. © 2010 NINTENDO. wii.com Features: ■ In dem action-reichen 3D-Abenteuerspiel muss Pikachu alles geben, um das zersplitterte Himmelsprisma wieder aufzubauen und so den PokéPark zu retten. -

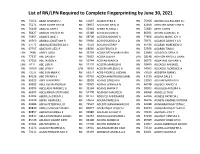

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021 RN 74156 ABAD CHARLES U RN 61837 ACASIO KYRA K RN 75958 ADVINCULA ROLAND D J RN 75271 ABAD GLORY GAY M RN 59937 ACCOUSTI NEAL O RN 42910 ADZUARA MARY JANE R RN 76449 ABALOS JUDY S RN 52918 ACEBO RUSSELL J RN 72683 AETO JUSTIN RN 38427 ABALOS TRICIA H M RN 43188 ACEVEDO JUNE D RN 86091 AFONG CLAREN C D RN 70657 ABANES JANE J RN 68208 ACIDERA NORIVIE S RN 72856 AGACID MARIE JOY H RN 46560 ABANIA JONATHAN R RN 59880 ACIO ROSARIO A D RN 78671 AGANOS DAWN Y A V RN 67772 ABARQUEZ BLESSILDA C RN 72528 ACKLIN JUSTIN P RN 85438 AGARAN NOBEMEN O RN 67707 ABATAYO LIEZL P RN 68066 ACOB FERLITA D RN 52928 AGARAN TINA K LPN 7498 ABBEY LORI J RN 35794 ACOBA BETH MARY BARN RN 33999 AGASID GLISERIA D RN 77337 ABE DAVID K RN 73632 ACOBA JULIA R LPN 18148 AGATON KRYSTLE LIAAN RN 57015 ABE JAYSON K RN 53744 ACOPAN MARK N RN 66375 AGBAYANI REYNANTE LPN 6111 ABE LORI R RN 55133 ACOSTA MARISSA R RN 58450 AGCAOILI ANNABEL RN 18300 ABE LYNN Y LPN 18682 ACOSTA MYLEEN G A RN 54002 AGCAOILI FLORENCE A RN 73517 ABE SUN-HWA K RN 69274 ACRE-PICKRELL ALEXAN RN 79169 AGDEPPA MARK J RN 84126 ABE TIFFANY K RN 45793 ACZON-ARMSTRONG MARI RN 41739 AGENA DALE S RN 69525 ABEE JENNIFER E RN 19550 ADAMS CAROLYN L RN 33363 AGLIAM MARILYN A RN 69992 ABEE KEVIN ANDREW RN 73979 ADAMS JENNIFER N RN 46748 AGLIBOT NANCY A RN 69993 ABELLADA MARINEL G RN 39164 ADAMS MARIA V RN 38303 AGLUGUB AURORA A RN 66502 ABELLANIDA STEPHANIE RN 52798 ADAMSKI MAUREEN RN 68068 AGNELLO TAI D RN 83403 ABERILLA JEREMY J RN 84737 ADDUCCI -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables.