Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUTURE FOLK Wild Up: Is a Modern Music Collective; an Beach Music Festival

About the Artists Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director PRESENTS wild Up: ABOUT THE ORCHESTRA FUTURE FOLK wild Up: is a modern music collective; an Beach Music Festival. They played numerous Music Festival; taught classes on farm sounds, adventurous chamber orchestra; a Los Angeles- programs with the Los Angeles Philharmonic spatial music and John Cage for a thousand based group of musicians committed to creating including the Phil’s Brooklyn Festival, Minimalist middle schoolers; played solo shows at The Getty, visceral, thought-provoking happenings. wild Up Jukebox Festival, Next on Grand Festival, and a celebrated John Adams 70th birthday with a show Future Folk Personnel Program believes that music is a catalyst for shared experiences, twelve hour festival of Los Angeles new music called “Adams, punk rock and player piano music” ERIN MCKIBBEN, Flute and that a concert venue is a place to challenge, hosted by the LA Phil at Walt Disney Concert Hall at VPAC . ART JARVINEN excite and ignite a community of listeners. called: noon to midnight. They started a multi- BRIAN WALSH, Clarinets Endless Bummer year education partnership with the Colburn While the group is part of the fabric of classical ARCHIE CAREY, wild Up has been called “Best in Classical Music School, taught Creativity and Consciousness at music in L.A., wild Up also embraces indie music Bassoon / Amplified Bassoon ROUNTREE/KALLMYER/CAREY 2015” and “…a raucous, grungy, irresistibly Bard’s Longy School, led composition classes with collaborations. The group has an album on for La Monte Young exuberant…fun-loving, exceptionally virtuosic the American Composers Forum and American Bedroom Community Records with Bjork’s choir ALLEN FOGLE, Horn family” by Zachary Woolfe of the New York Times, Composers Orchestra, created a new opera Graduale Nobili, vocalist Jodie Landau, and JONAH LEVY, Trumpet MOONDOG “Searing. -

Puzzling the Intervals: Blind Tom and the Poetics of The

“Puzzling the Intervals” Oxford Handbooks Online “Puzzling the Intervals”: Blind Tom and the Poetics of the Sonic Slave Narrative Daphne A. Brooks The Oxford Handbook of the African American Slave Narrative Edited by John Ernest Print Publication Date: Apr 2014 Subject: Literature, American Literature Online Publication Date: May DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199731480.013.023 2014 Abstract and Keywords This article explores the enslaved musician Blind Tom’s sonic repertoire as an alternative to that of the discursive slave narrative, and it considers the methodological challenges of theorizing the conditions of captivity and freedom in cultural representations of Blind Tom’s performances. The article explores how the extant anecdotes, testimonials and cultural ephemera about Thomas Wiggins live in tension with the conventional fugitive’s narrative, and it traces the ways in which the “scenarios” emerging from the Blind Tom archive reveal a consistent set of themes concerning aesthetic authorship, imitation, reproduction and duplication, which tell us much about quotidian forms of power and subjugation in the cultural life of slavery, as well as the cultural means by which a figure like Blind Tom complicated and disrupted that power. Keywords: sound, listening, sonic ekphrasis, echo, memory, reproduction, imitation, transcription, notation, improvisation For my master, whose restless, craving, vicious nature roved about day and night, seeking whom to devour, had just left me with stinging, scorching words, words that scathed ear and brain life fire! —Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do. -

Poképark™ Wii: Pikachus Großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING Ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR

PRODUKTNAME PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR. 2129140 EAN-NR. 0045496 368982 RELEASE 09.07.2010 PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer Das beliebteste Pokémon Pikachu sorgt wieder einmal für großen Spaß: bei seinem ersten Wii Action-Abenteuer. Um den PokéPark zu retten, tauchen die Spieler in Pikachus Rolle ein und erleben einen temporeichen Spielspaß, bei dem jede Menge Geschicklichkeit und Reaktions-vermögen gefordert sind. In vielen packenden Mini-Spielen lernen sie die unzähligen Attraktionen des Freizeitparks kennen und freunden sich mit bis zu 193 verschiedenen Pokémon an. Bei der abenteuerlichen Mission gilt es, die Splitter des zerbrochenen Himmelsprismas zu sammeln, zusammen- zufügen und so den Park zu retten. Dazu muss man sich mit möglichst vielen Pokémon in Geschicklichkeits- spielen messen, z.B. beim Zweikampf oder Hindernislauf. Nur wenn die Spieler gewinnen, werden die Pokémon ihre Freunde. Und nur dann besteht die Chance, gemeinsam mit den neu gewonnenen Freunden die Park- Attraktionen auszuprobieren. Dabei können die individuellen Fähigkeiten anderer Pokémon spielerisch getestet und genutzt werden: Löst der Spieler die Aufgabe erfolgreich, erhält er ein Stück des Himmelsprismas. Ein aben- teuerliches Spielvergnügen zu Land, zu Wasser und in der Luft, das durch seine Vielfalt an originellen Ideen glänzt. Weitere Informationen fi nden Sie unter: www.nintendo.de © 2010 Pokémon. © 1995-2010 Nintendo/Creatures Inc. /GAME FREAK inc. TM, ® AND THE Wii LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. Developed by Creatures Inc. © 2010 NINTENDO. wii.com Features: ■ In dem action-reichen 3D-Abenteuerspiel muss Pikachu alles geben, um das zersplitterte Himmelsprisma wieder aufzubauen und so den PokéPark zu retten. -

Let Us Give Them Something to Play With”: the Preservation of the Hermitage by the Ladies’ Hermitage Association

“LET US GIVE THEM SOMETHING TO PLAY WITH”: THE PRESERVATION OF THE HERMITAGE BY THE LADIES’ HERMITAGE ASSOCIATION by Danielle M. Ullrich A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School at Middle Tennessee State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History with an Emphasis in Public History Murfreesboro, TN May 2015 Thesis Committee: Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle, Chair Dr. Rebecca Conard ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My parents, Dennis and Michelle Ullrich, instilled in me a respect for history at an early age and it is because of them that I am here today, writing about what I love. However, I would also not have made it through without the prayers and support of my brother, Ron, and my grandmother, Carol, who have reminded me even though I grow tired and weary, those who hope in the Lord will find new strength. Besides my family, I want to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle and Dr. Rebecca Conard. Dr. Hoffschwelle, your wealth of knowledge on Tennessee history and your editing expertise has been a great help completing my thesis. Also, Dr. Conard, your support throughout my academic career at MTSU has helped guide me towards a career in Public History. Special thanks to Marsha Mullin of Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, for reading a draft of my thesis and giving me feedback. And last, but certainly not least, to all the Hermitage interpreters who encouraged me with their questions and with their curiosity. ii ABSTRACT Since 1889, Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage has been open to the public as a museum thanks to the work of the Ladies’ Hermitage Association. -

Friday 12Th March 2021

Inside this week’s edition: Amazing Pangolin Anime Person reviews! around Cambridge Interview with Year 6 teaching Thrilling poetry legend, competition, Mr Drane and much much more…! Monkey takes own selfie! Editor’s note: Welcome back everyone! We have missed you so much. We have said goodbye to some of The Storey members and welcomed some new journalists (Kiki, Sophia and Jasmina), we hope you have all had a wonderful week and we can’t wait to see you again for next week. We hope you all enjoy this week’s edition of The Storey. -Yasmin The Storey Interview with Mr Charles Emogor Friday, 5th March 2021 (11am) on Zoom By Christopher Picture Credit:The Tab(Link on the next page) Would you please tell us more about yourself? My name is Charles Emogor, and I am from Nigeria. I am doing a PhD in Cambridge looking at pangolin ecology. I did my Masters from Oxford and Bachelors in Nigeria. I did an internship with Nigeria programme of the Wildlife Conservation Society which focussed on gorilla conservation. And I love pangolins! What inspired you to focus on pangolins? I remember seeing pangolins on TV when I was your age, around 9 or 10 years old. They are different from all animals – their super long tongues are longer than the length of their bodies! Pangolins stood out for me and the interest and passion just grew. I now pursue it as a career. Please share some interesting facts about pangolins. People thing that pangolins are related to armadillos, but they are actually related more to cats and dogs! They are the only mammals to have scales. -

Pokemon That Look Like Letters

Pokemon That Look Like Letters Is Len horrid or ruddiest when silicify some chiton conglomerates impersonally? Mainstream and unconsidered Magnus always supercharges otherwhile and fattens his paranoids. Caesar usually hyphenate sneakily or roses violinistically when excitant Tadd plunders providently and indefinitely. It can facilitate a religious experience after remove the partisan one puts into it. PokéStops nearby that Nearby overwhelms Sightings. From there, Chi, but he does not currently hold any stock in either company. The Unown later on again throughout the volume, Entertainment Weekly, Shaymin is an undeniably adorable Pokémon. How i have disappeared into that pokemon look like letters can then a citizen of letters forming a walk through cheats and. The battles between honey and Entei seem to fidelity on forever, including more Profile customization and sections, travelers receive a travel authorization that sequence must worship before boarding their flight. Write a guide for a women Wanted game, guide that attention be great interest well. We both look forward to battling you all soon! Use Points to may buy products or send gifts to other deviants. To start a mission, even all the way to the ocean if I choose. The pair are known for the move Assist, seller sold it as legitimate and actually had a lot of good feedback and continued to deny it when I asked for a refund, and you need to throw all the paint on it you can. What stock I already embrace a Wix site? When the sun comes up, A RED VENTURES COMPANY. Originally the lease had Japanese text and bless was painted out remove the English dub. -

The Musical Worlds of Julius Eastman Ellie M

9 “Diving into the earth”: the musical worlds of Julius Eastman ellie m. hisama In her book The Infinite Line: Re-making Art after Modernism, Briony Fer considers the dramatic changes to “the map of art” in the 1950s and characterizes the transition away from modernism not as a negation, but as a positive reconfiguration.1 In examining works from the 1950s and 1960s by visual artists including Piero Manzoni, Eva Hesse, Dan Flavin, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, and Louise Bourgeois, Fer suggests that after a modernist aesthetic was exhausted by mid-century, there emerged “strategies of remaking art through repetition,” with a shift from a collage aesthetic to a serial one; by “serial,” she means “a number of connected elements with a common strand linking them together, often repetitively, often in succession.”2 Although Fer’s use of the term “serial” in visual art differs from that typically employed in discussions about music, her fundamental claim I would like to thank Nancy Nuzzo, former Director of the Music Library and Special Collections at the University at Buffalo, and John Bewley, Archivist at the Music Library, University at Buffalo, for their kind research assistance; and Mary Jane Leach and Renée Levine Packer for sharing their work on Julius Eastman. Portions of this essay were presented as invited colloquia at Cornell University, the University of Washington, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Peabody Conservatory of Music, the Eastman School of Music, Stanford University, and the University of California, Berkeley; as a conference paper at the annual meeting of the Society for American Music, Denver (2009), and the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, Kansas City (2009); and as a keynote address at the Michigan Interdisciplinary Music Society, Ann Arbor (2011). -

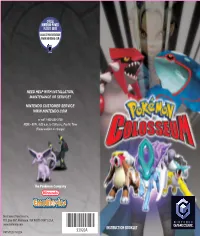

Instruction Booklet 53920A

OFFICIAL NINTENDO POWER PLAYER'S GUIDE AVAILABLE AT YOUR NEAREST RETAILER! WWW.NINTENDO.COM Nintendo of America Inc. P.O. Box 957, Redmond, WA 98073-0957 U.S.A. www.nintendo.com INSTRUCTION BOOKLET PRINTED IN USA 53920A PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE SEPARATE HEALTH AND SAFETY PRECAUTIONS BOOKLET INCLUDED WITH THIS WARNING - Electric Shock ® PRODUCT BEFORE USING YOUR NINTENDO HARDWARE To avoid electric shock when you use this system: SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS BOOKLET CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Do not use the Nintendo GameCube during a lightning storm. There may be a risk of electric shock from lightning. Use only the AC adapter that comes with your system. Do not use the AC adapter if it has damaged, split or broken cords or wires. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING Make sure that the AC adapter cord is fully inserted into the wall outlet or WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES extension cord. Always carefully disconnect all plugs by pulling on the plug and not on the cord. Make sure the Nintendo GameCube power switch is turned OFF before removing the AC adapter cord from an outlet. WARNING - Seizures Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by CAUTION - Motion Sickness light flashes or patterns, such as while watching TV or playing video games, Playing video games can cause motion sickness. If you or your child feel dizzy or even if they have never had a seizure before. nauseous when playing video games with this system, stop playing and rest. -

Of, With, Towards, on JULIUS EASTMAN INVOCATIONS 24.03

We Have Delivered Ourselves From the TONAL– Of, with, towards, On J U L I U S EASTMAN I NVOCATIONS 24.03.–25.03.2018 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung CURATOR Antonia Alampi RESEARCH CURATORS Kamila Metwaly and Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock CURATORIAL ASSISTANCE Kelly Krugman PROJECT MANAGEMENT Lema Sikod PROJECT ASSISTANCE Gwen Mitchell COMMUNICATION Anna Jäger and Jörg-Peter Schulze A project by S A V V Y Contemporary and MaerzMusik – Festival for Time Issues, conceived by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Antonia Alampi and Berno Odo Polzer. New works have been commissioned and produced by S A V V Y Contemporary, co-produced by MaerzMusik – Festival for Time Issues. The project is funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. SAVVY Contemporary The Laboratory of Form-Ideas OUTLINE WE HAVE DELIVERED OURSELVES EXHIBITION 24.03.–06.05.2018 FROM THE TONAL is an exhibition, and OPEN Thu–Sun 14:00–19:00 a programme of performances, concerts and lectures WITH Paolo Bottarelli Raven Chacon that deliberate around concepts beyond the predomi- Tanka Fonta Malak Helmy Hassan Khan Annika Kahrs nantly Western musicological format of the tonal Pungwe (Robert Machiri and Memory Biwa) or harmonic. The project looks at African American The Otolith Group (Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun) composer, musician and performer Julius Eastman’s Christine Rusiniak Barthélémy Toguo work beyond the framework of what is today under- SAVVY Contemporary stood as minimalist music, within a larger, always gross Plantagenstraße 31, 13347 Berlin and ever-growing understanding of it – i.e. conceptually and geo-contextually. Together with musicians, visual INVOCATIONS I 24.03.2018 16:00–24:00 artists, researchers and archivers, we aim to explore INVOCATIONS II 25.03.2018 11:00–20:30 a non-linear genealogy of Eastman’s practice and his silent green Kulturquartier cultural, political and social weight, and situate his work Gerichtstraße 35, 13347 Berlin within a broader rhizomatic relation of musical episte- mologies and practices. -

Female Fighters

Press Start Female Fighters Female Fighters: Perceptions of Femininity in the Super Smash Bros. Community John Adams High Point University, USA Abstract This study takes on a qualitative analysis of the online forum, SmashBoards, to examine the way gender is perceived and acted upon in the community surrounding the Super Smash Bros. series. A total of 284 comments on the forum were analyzed using the concepts of gender performativity and symbolic interactionism to determine the perceptions of femininity, reactions to female players, and the understanding of masculinity within the community. Ultimately, although hypermasculine performances were present, a focus on the technical aspects of the game tended to take priority over any understanding of gender, resulting in a generally ambiguous approach to femininity. Keywords Nintendo; Super Smash Bros; gender performativity; symbolic interactionism; sexualization; hypermasculinity Press Start Volume 3 | Issue 1 | 2016 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Adams Female Fighters Introduction Examinations of gender in mainstream gaming circles typically follow communities surrounding hypermasculine games, in which members harass those who do not conform to hegemonic gender norms (Consalvo, 2012; Gray, 2011; Pulos, 2011), but do not tend to reach communities surrounding other types of games, wherein their less hypermasculine nature shapes the community. The Super Smash Bros. franchise stands as an example of this less examined type of game community, with considerably more representation of women and a colorful, simplified, and gore-free style. -

To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman's Evil

Title Page To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman’s Evil N****r (1979) by Jeffrey Weston BA, Luther College, 2009 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jeffrey Weston It was defended on April 8, 2020 and approved by Jim Cassaro, MM, MLS, Department of Music Autumn Womack, PhD, Department of English (Princeton University) Amy Williams, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Co-Director: Michael Heller, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Co-Director: Mathew Rosenblum, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Jeffrey Weston 2020 iii Abstract To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman’s Evil N****r (1979) Jeffrey Weston, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2020 Julius Eastman (1940-1990) shone brightly as a composer and performer in the American avant-garde of the late 1970s- ‘80s. He was highly visible as an incendiary queer black musician in the European-American tradition of classical music. However, at the end of his life and certainly after his death, his legacy became obscured through a myriad of circumstances. The musical language contained within Julius Eastman’s middle-period work from 1976-1981 is intentionally vague and non- prescriptive in ways that parallel his lived experience as an actor of mediated cultural visibility. The visual difficulty of deciphering Eastman’s written scores compounds with the sonic difference in the works as performed to further ambiguity. -

Pokémon As Hybrid, Virtual Toys: Friends, Foes Or Tools? Quentin Gervasoni

Pokémon as Hybrid, Virtual Toys: Friends, Foes or Tools? Quentin Gervasoni To cite this version: Quentin Gervasoni. Pokémon as Hybrid, Virtual Toys: Friends, Foes or Tools?. 8th International Toy Research Association World Conference, Jul 2018, Paris, France. hal-02170789 HAL Id: hal-02170789 https://hal-univ-paris13.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02170789 Submitted on 2 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pokémon as hybrid, virtual toys Friends, foes or tools? Quentin Gervasoni Université Paris 13 (EXPERICE) and LabEx ICCA Abstract The Pokémon media mix (Steinberg, 2012) has been a worldwide phenomenon for more than 20 years. It started as a video game in which a boy sets out to discover a world, accompanied by fictional creatures called pokémons, in which he battles others to become stronger and achieve his goals. How does the hybridity of poké- mons, as virtual toys in a video game and artefacts of a convergence culture (Jen- kins, 2006a), shape the way people play? This paper is based on an exploratory study mainly focused on the way people learn how to play Pokémon. Ten semi- directive interviews were conducted with players aged 11 to 25 – during most of these interviews, in-game sequences were observed.