The Music of Julius Eastman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUTURE FOLK Wild Up: Is a Modern Music Collective; an Beach Music Festival

About the Artists Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director PRESENTS wild Up: ABOUT THE ORCHESTRA FUTURE FOLK wild Up: is a modern music collective; an Beach Music Festival. They played numerous Music Festival; taught classes on farm sounds, adventurous chamber orchestra; a Los Angeles- programs with the Los Angeles Philharmonic spatial music and John Cage for a thousand based group of musicians committed to creating including the Phil’s Brooklyn Festival, Minimalist middle schoolers; played solo shows at The Getty, visceral, thought-provoking happenings. wild Up Jukebox Festival, Next on Grand Festival, and a celebrated John Adams 70th birthday with a show Future Folk Personnel Program believes that music is a catalyst for shared experiences, twelve hour festival of Los Angeles new music called “Adams, punk rock and player piano music” ERIN MCKIBBEN, Flute and that a concert venue is a place to challenge, hosted by the LA Phil at Walt Disney Concert Hall at VPAC . ART JARVINEN excite and ignite a community of listeners. called: noon to midnight. They started a multi- BRIAN WALSH, Clarinets Endless Bummer year education partnership with the Colburn While the group is part of the fabric of classical ARCHIE CAREY, wild Up has been called “Best in Classical Music School, taught Creativity and Consciousness at music in L.A., wild Up also embraces indie music Bassoon / Amplified Bassoon ROUNTREE/KALLMYER/CAREY 2015” and “…a raucous, grungy, irresistibly Bard’s Longy School, led composition classes with collaborations. The group has an album on for La Monte Young exuberant…fun-loving, exceptionally virtuosic the American Composers Forum and American Bedroom Community Records with Bjork’s choir ALLEN FOGLE, Horn family” by Zachary Woolfe of the New York Times, Composers Orchestra, created a new opera Graduale Nobili, vocalist Jodie Landau, and JONAH LEVY, Trumpet MOONDOG “Searing. -

Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Julius Eastman: The Sonority of Blackness Otherwise Isaac Alexandre Jean-Francois The composer and singer Julius Dunbar Eastman (1940-1990) was a dy- namic polymath whose skill seemed to ebb and flow through antagonism, exception, and isolation. In pushing boundaries and taking risks, Eastman encountered difficulty and rejection in part due to his provocative genius. He was born in New York City, but soon after, his mother Frances felt that the city was unsafe and relocated Julius and his brother Gerry to Ithaca, New York.1 This early moment of movement in Eastman’s life is significant because of the ways in which flight operated as a constitutive feature in his own experience. Movement to a “safer” place, especially to a predomi- nantly white area of New York, made it more difficult for Eastman to ex- ist—to breathe. The movement from a more diverse city space to a safer home environ- ment made it easier for Eastman to take private lessons in classical piano but made it more complicated for him to find embodied identification with other black or queer people. 2 Movement, and attention to the sonic remnants of gesture and flight, are part of an expansive history of black people and journey. It remains dif- ficult for a black person to occupy the static position of composer (as op- posed to vocalist or performer) in the discipline of classical music.3 In this vein, Eastman was often recognized and accepted in performance spaces as a vocalist or pianist, but not a composer.4 George Walker, the Pulitzer- Prize winning composer and performer, shares a poignant reflection on the troubled status of race and classical music reception: In 1987 he stated, “I’ve benefited from being a Black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by Black composers, I would get perfor- mances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works. -

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

"For Philip Guston" by Petr Kotik and Walter Zimmermann

[Morton Feldman Page] [List of Texts] On Performing Feldman's "For Philip Guston": A Conversation by Petr Kotik and Walter Zimmermann Contents: Introduction to Petr Kotik/Walter Zimmermann Conversation by Petr Kotik Ten Nasty Questions put to Petr Kotik by Walter Zimmermann Introduction to Petr Kotik/Walter Zimmermann Conversation Following the performance by S.E.M. Ensemble of Morton Feldman's For Philip Guston at the Paula Cooper Gallery in May, 1995, Paula Cooper suggested that we record the piece. She offered to fund the project the same way she funded our Marcel Duchamp recording in 1989. We had a few meetings in the Fall of 1995, to assess the feasibility of the idea and in November, we decided to go ahead. On December 22 and 23, 1995, we recorded the piece at the LRP Studio on West 22nd Street in Manhattan. The May '95 performance of Guston at the Paula Cooper Gallery was a great success. That Spring, we performed the piece twice: once in New York and few weeks later at the Landesmuseum Mainz in Germany. These were not our first performances of Guston. We have already performed it in 1988. Both concerts in 1995 convinced me that the time has finally come for music of extended duration to be appreciated by broader audiences. I was very much involved with this concept in the 1970s. In fact, all the pieces I wrote between 1971 and 1981 are several hours in duration. In the Summer of 1987, I wanted to commission Feldman to write a piece for the S.E.M. -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

The Musical Worlds of Julius Eastman Ellie M

9 “Diving into the earth”: the musical worlds of Julius Eastman ellie m. hisama In her book The Infinite Line: Re-making Art after Modernism, Briony Fer considers the dramatic changes to “the map of art” in the 1950s and characterizes the transition away from modernism not as a negation, but as a positive reconfiguration.1 In examining works from the 1950s and 1960s by visual artists including Piero Manzoni, Eva Hesse, Dan Flavin, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, and Louise Bourgeois, Fer suggests that after a modernist aesthetic was exhausted by mid-century, there emerged “strategies of remaking art through repetition,” with a shift from a collage aesthetic to a serial one; by “serial,” she means “a number of connected elements with a common strand linking them together, often repetitively, often in succession.”2 Although Fer’s use of the term “serial” in visual art differs from that typically employed in discussions about music, her fundamental claim I would like to thank Nancy Nuzzo, former Director of the Music Library and Special Collections at the University at Buffalo, and John Bewley, Archivist at the Music Library, University at Buffalo, for their kind research assistance; and Mary Jane Leach and Renée Levine Packer for sharing their work on Julius Eastman. Portions of this essay were presented as invited colloquia at Cornell University, the University of Washington, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Peabody Conservatory of Music, the Eastman School of Music, Stanford University, and the University of California, Berkeley; as a conference paper at the annual meeting of the Society for American Music, Denver (2009), and the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, Kansas City (2009); and as a keynote address at the Michigan Interdisciplinary Music Society, Ann Arbor (2011). -

Of, With, Towards, on JULIUS EASTMAN INVOCATIONS 24.03

We Have Delivered Ourselves From the TONAL– Of, with, towards, On J U L I U S EASTMAN I NVOCATIONS 24.03.–25.03.2018 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung CURATOR Antonia Alampi RESEARCH CURATORS Kamila Metwaly and Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock CURATORIAL ASSISTANCE Kelly Krugman PROJECT MANAGEMENT Lema Sikod PROJECT ASSISTANCE Gwen Mitchell COMMUNICATION Anna Jäger and Jörg-Peter Schulze A project by S A V V Y Contemporary and MaerzMusik – Festival for Time Issues, conceived by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Antonia Alampi and Berno Odo Polzer. New works have been commissioned and produced by S A V V Y Contemporary, co-produced by MaerzMusik – Festival for Time Issues. The project is funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. SAVVY Contemporary The Laboratory of Form-Ideas OUTLINE WE HAVE DELIVERED OURSELVES EXHIBITION 24.03.–06.05.2018 FROM THE TONAL is an exhibition, and OPEN Thu–Sun 14:00–19:00 a programme of performances, concerts and lectures WITH Paolo Bottarelli Raven Chacon that deliberate around concepts beyond the predomi- Tanka Fonta Malak Helmy Hassan Khan Annika Kahrs nantly Western musicological format of the tonal Pungwe (Robert Machiri and Memory Biwa) or harmonic. The project looks at African American The Otolith Group (Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun) composer, musician and performer Julius Eastman’s Christine Rusiniak Barthélémy Toguo work beyond the framework of what is today under- SAVVY Contemporary stood as minimalist music, within a larger, always gross Plantagenstraße 31, 13347 Berlin and ever-growing understanding of it – i.e. conceptually and geo-contextually. Together with musicians, visual INVOCATIONS I 24.03.2018 16:00–24:00 artists, researchers and archivers, we aim to explore INVOCATIONS II 25.03.2018 11:00–20:30 a non-linear genealogy of Eastman’s practice and his silent green Kulturquartier cultural, political and social weight, and situate his work Gerichtstraße 35, 13347 Berlin within a broader rhizomatic relation of musical episte- mologies and practices. -

A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century

A SCENE WITHOUT A NAME: INDIE CLASSICAL AND AMERICAN NEW MUSIC IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY William Robin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Mark Katz Andrea Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Benjamin Piekut © 2016 William Robin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT WILLIAM ROBIN: A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century (Under the direction of Mark Katz) This dissertation represents the first study of indie classical, a significant subset of new music in the twenty-first century United States. The definition of “indie classical” has been a point of controversy among musicians: I thus examine the phrase in its multiplicity, providing a framework to understand its many meanings and practices. Indie classical offers a lens through which to study the social: the web of relations through which new music is structured, comprised in a heterogeneous array of actors, from composers and performers to journalists and publicists to blog posts and music venues. This study reveals the mechanisms through which a musical movement establishes itself in American cultural life; demonstrates how intermediaries such as performers, administrators, critics, and publicists fundamentally shape artistic discourses; and offers a model for analyzing institutional identity and understanding the essential role of institutions in new music. Three chapters each consider indie classical through a different set of practices: as a young generation of musicians that constructed itself in shared institutional backgrounds and performative acts of grouping; as an identity for New Amsterdam Records that powerfully shaped the record label’s music and its dissemination; and as a collaboration between the ensemble yMusic and Duke University that sheds light on the twenty-first century status of the new-music ensemble and the composition PhD program. -

Art Movements Referenced : Artists from France: Paintings and Prints from the Art Museum Collection

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING ART MUSEUM 2009 Art Movements Referenced : Artists from France: Paintings and Prints from the Art Museum Collection OVERVIEW Sarah Bernhardt. It was an overnight sensation, and Source: www.wikipedia.org/ announced the new artistic style and its creator to The following movements are referenced: the citizens of Paris. Initially called the Style Mucha, (Mucha Style), this soon became known as Art Art Nouveau Les Nabis Nouveau. The Barbizon School Modernism Art Nouveau’s fifteen-year peak was most strongly Cubism Modern Art felt throughout Europe—from Glasgow to Moscow Dadaism Pointillism to Madrid — but its influence was global. Hence, it Les Fauves Surrealism is known in various guises with frequent localized Impressionism Symbolism tendencies. In France, Hector Guimard’s metro ART NOUVEau entrances shaped the landscape of Paris and Emile Gallé was at the center of the school of thought Art Nouveau is an international movement and in Nancy. Victor Horta had a decisive impact on style of art, architecture and applied art—especially architecture in Belgium. Magazines like Jugend helped the decorative arts—that peaked in popularity at the spread the style in Germany, especially as a graphic turn of the 20th century (1890–1905). The name ‘Art artform, while the Vienna Secessionists influenced art nouveau’ is French for ‘new art’. It is also known as and architecture throughout Austria-Hungary. Art Jugendstil, German for ‘youth style’, named after the Nouveau was also a movement of distinct individuals magazine Jugend, which promoted it, and in Italy, such as Gustav Klimt, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Stile Liberty from the department store in London, Alphonse Mucha, René Lalique, Antoni Gaudí and Liberty & Co., which popularized the style. -

Programme Notes

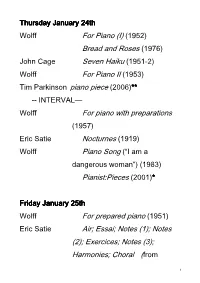

Thursday January 24th Wolff For Piano (I) (1952) Bread and Roses (1976) John Cage Seven Haiku (1951-2) Wolff For Piano II (1953) Tim Parkinson piano piece (2006)****** -- INTERVAL— Wolff For piano with preparations (1957) Eric Satie Nocturnes (1919) Wolff Piano Song (“I am a dangerous woman”) (1983) Pianist:Pieces (2001) *** Friday January 25th Wolff For prepared piano (1951) Eric Satie Air; Essai; Notes (1); Notes (2); Exercices; Notes (3); Harmonies; Choral (from 1 'Carnet d'esquisses et do croquis', 1900-13 ) Wolff A Piano Piece (2006) *** Charles Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) Steve Chase Piano Dances (2007-8) ****** Wolff Accompaniments (1972) --INTERVAL— Wolff Eight Days a Week Variation (1990) Cornelius Cardew Father Murphy (1973) Howard Skempton Whispers (2000) Wolff Preludes 1-11 (1980-1) Saturday January 26th Christopher Fox at the edge of time (2007) *** Wolff Studies (1974-6) Michael Parsons Oblique Pieces 8 and 9 (2007) ****** 2 Wolff Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida (1979) --INTERVAL-- Wolff Suite (I) (1954) For pianist (1959) Webern Variations (1936) Wolff Touch (2002) *** (** denotes world premiere; *** denotes UK premiere) for pianist: the piano music of Christian Wolff Given the importance within Christian Wolff’s compositional aesthetic of music which involves interaction between players, it is perhaps surprising that there is a significant body of works for solo instrument. In particular the piano proves to be central 3 to Wolff’s output, from the early 1950s to the present day. These concerts include no fewer than sixteen piano solos; I have chosen not to include a number of other works for indeterminate instrumentation which are well suited to the piano (the Tilbury pieces for example) as well as two recent anthologies of short pieces, A Keyboard Miscellany and Incidental Music , and also Long Piano (Peace March 11) of which I gave the European premiere in 2007.