LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

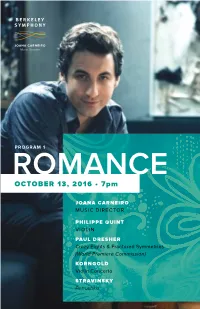

Berkeleysymphonyprogram2016

Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. We are now able to provide all funeral, cremation and celebratory services for our families and our community at our 223 acre historic location. For our families and friends, the single site combination of services makes the difficult process of making funeral arrangements a little easier. We’re able to provide every facet of service at our single location. We are also pleased to announce plans to open our new chapel and reception facility – the Water Pavilion in 2018. Situated between a landscaped garden and an expansive reflection pond, the Water Pavilion will be perfect for all celebrations and ceremonies. Features will include beautiful kitchen services, private and semi-private scalable rooms, garden and water views, sunlit spaces and artful details. The Water Pavilion is designed for you to create and fulfill your memorial service, wedding ceremony, lecture or other gatherings of friends and family. Soon, we will be accepting pre-planning arrangements. For more information, please telephone us at 510-658-2588 or visit us at mountainviewcemetery.org. Berkeley Symphony 2016/17 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 14 Season Sponsors 18 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 21 Program 25 Program Notes 39 Music Director: Joana Carneiro 43 Artists’ Biographies 51 Berkeley Symphony 55 Music in the Schools 57 2016/17 Membership Benefits 59 Annual Membership Support 66 Broadcast Dates Mountain View Cemetery Association, a historic Olmsted designed cemetery located in the foothills of 69 Contact Oakland and Piedmont, is pleased to announce the opening of Piedmont Funeral Services. -

A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century

A SCENE WITHOUT A NAME: INDIE CLASSICAL AND AMERICAN NEW MUSIC IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY William Robin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Mark Katz Andrea Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Benjamin Piekut © 2016 William Robin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT WILLIAM ROBIN: A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century (Under the direction of Mark Katz) This dissertation represents the first study of indie classical, a significant subset of new music in the twenty-first century United States. The definition of “indie classical” has been a point of controversy among musicians: I thus examine the phrase in its multiplicity, providing a framework to understand its many meanings and practices. Indie classical offers a lens through which to study the social: the web of relations through which new music is structured, comprised in a heterogeneous array of actors, from composers and performers to journalists and publicists to blog posts and music venues. This study reveals the mechanisms through which a musical movement establishes itself in American cultural life; demonstrates how intermediaries such as performers, administrators, critics, and publicists fundamentally shape artistic discourses; and offers a model for analyzing institutional identity and understanding the essential role of institutions in new music. Three chapters each consider indie classical through a different set of practices: as a young generation of musicians that constructed itself in shared institutional backgrounds and performative acts of grouping; as an identity for New Amsterdam Records that powerfully shaped the record label’s music and its dissemination; and as a collaboration between the ensemble yMusic and Duke University that sheds light on the twenty-first century status of the new-music ensemble and the composition PhD program. -

Read a Complete Transcript of the Interview

In the 1st Person : March 2005 NewMusicBox The Inside Story: Stephen Scott talks with Frank J. Oteri Friday, November 12, 2004—4:30-5:30 p.m. The American Music Center Videotaped by Randy Nordschow Transcribed by Randy Nordschow and Frank J. Oteri Like much of the music I love, Stephen Scott's music first entered my life on an LP. It was over 20 years ago, when I was a DJ at Columbia University's radio station WKCR. Stephen Scott's LP, New Music for Bowed Piano, arrived in the mail with two others—one featuring music by Ingram Marshall, the other by Paul Dresher—all on a record label I had never heard of before called New Albion. In the years since, I've actively followed the careers of all three, both as a listener and someone who writes about music. I've talked with Ingram for NewMusicBox and I've written program notes about Paul Dresher. But, until now, I was never able to verbally catch up with Stephen Scott until he came to visit us at the American Music Center. In some ways, Stephen Scott is the most methodical of these three postminimalist composers who all made minimalism less methodical in very different ways. Not in terms of compositional techniques, but in terms of his sonic vocabulary: all of his work on recordings and most of the music he composes is for his own ensemble of musicians who bow, hammer, scrape, and do any number of other activities inside a grand piano. To this day, aside from this brief video of his piece Entrada, I've never "seen" his music live. -

Art Movements Referenced : Artists from France: Paintings and Prints from the Art Museum Collection

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING ART MUSEUM 2009 Art Movements Referenced : Artists from France: Paintings and Prints from the Art Museum Collection OVERVIEW Sarah Bernhardt. It was an overnight sensation, and Source: www.wikipedia.org/ announced the new artistic style and its creator to The following movements are referenced: the citizens of Paris. Initially called the Style Mucha, (Mucha Style), this soon became known as Art Art Nouveau Les Nabis Nouveau. The Barbizon School Modernism Art Nouveau’s fifteen-year peak was most strongly Cubism Modern Art felt throughout Europe—from Glasgow to Moscow Dadaism Pointillism to Madrid — but its influence was global. Hence, it Les Fauves Surrealism is known in various guises with frequent localized Impressionism Symbolism tendencies. In France, Hector Guimard’s metro ART NOUVEau entrances shaped the landscape of Paris and Emile Gallé was at the center of the school of thought Art Nouveau is an international movement and in Nancy. Victor Horta had a decisive impact on style of art, architecture and applied art—especially architecture in Belgium. Magazines like Jugend helped the decorative arts—that peaked in popularity at the spread the style in Germany, especially as a graphic turn of the 20th century (1890–1905). The name ‘Art artform, while the Vienna Secessionists influenced art nouveau’ is French for ‘new art’. It is also known as and architecture throughout Austria-Hungary. Art Jugendstil, German for ‘youth style’, named after the Nouveau was also a movement of distinct individuals magazine Jugend, which promoted it, and in Italy, such as Gustav Klimt, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Stile Liberty from the department store in London, Alphonse Mucha, René Lalique, Antoni Gaudí and Liberty & Co., which popularized the style. -

Lou Harrison Centennial EVA SOLTES EVA

Please turn off all electronic Photography and audio/video recording devices before entering the in the performance hall are prohibited. performance hall. Lou Harrison Centennial EVA SOLTES EVA DEPARTMENT OF These performances are made possible in part by: PERFORMING ARTS, MUSIC, The P. J. McMyler Musical Endowment Fund AND FILM The Ernest L. and Louise M. Gartner Fund The Cleveland Museum of Art The Anton and Rose Zverina Music Fund 11150 East Boulevard The Frank and Margaret Hyncik Memorial Fund Cleveland, Ohio 44106–1797 The Adolph Benedict and Ila Roberts Schneider Fund The Arthur, Asenath, and Walter H. Blodgett Memorial Fund [email protected] The Dorothy Humel Hovorka Endowment Fund cma.org/performingarts The Albertha T. Jennings Musical Arts Fund #CMAperformingarts Programs are subject to change. Series sponsors: Friday, October 20, 2017 TICKETS 1–888–CMA–0033 cma.org/performingarts Welcome to the PerformingLou Harrison Arts 2017–18 Centennial Cleveland Museum of Art Friday, October 20, 2017, 7:30 p.m. cma.org/performingartsGartner Auditorium, the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Museum of Art’s performing arts series #CMAperformingarts offers a fascinating concert calendar notable for its boundless multiplicity. This year, visits from old friends Chamber Music in the Galleries CIM Organ Studio Wednesday, October 4, 6:00 Sunday, March 11, 2:00 and new bring century-spanning music from around the Mr. Harrison’s Gamelans globe, exploring cultural connections that link the human Butler, Bernstein & the Hot 9 Wu Man & heart and spirit. Wednesday, October 11, 7:30 Huayin Shadow Puppet Band Suite for Violin and Wednesday,Lou Harrison March 21, (1917–2003) 7:30 Lou Harrison Centennial American Gamelan (1973) & Richard Dee In the Galleries Friday, October 20, 7:30 Chamber Music in the Galleries 1. -

Echoes of the Avant-Garde in American Minimalist Opera

ECHOES OF THE AVANT-GARDE IN AMERICAN MINIMALIST OPERA Ryan Scott Ebright A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Mark Katz Tim Carter Brigid Cohen Annegret Fauser Philip Rupprecht © 2014 Ryan Scott Ebright ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ryan Scott Ebright: Echoes of the Avant-garde in American Minimalist Opera (Under the direction of Mark Katz) The closing decades of the twentieth century witnessed a resurgence of American opera, led in large part by the popular and critical success of minimalism. Based on repetitive musical structures, minimalism emerged out of the fervid artistic intermingling of mid twentieth- century American avant-garde communities, where music, film, dance, theater, technology, and the visual arts converged. Within opera, minimalism has been transformational, bringing a new, accessible musical language and an avant-garde aesthetic of experimentation and politicization. Thus, minimalism’s influence invites a reappraisal of how opera has been and continues to be defined and experienced at the turn of the twenty-first century. “Echoes of the Avant-garde in American Minimalist Opera” offers a critical history of this subgenre through case studies of Philip Glass’s Satyagraha (1980), Steve Reich’s The Cave (1993), and John Adams’s Doctor Atomic (2005). This project employs oral history and archival research as well as musical, dramatic, and dramaturgical analyses to investigate three interconnected lines of inquiry. The first traces the roots of these operas to the aesthetics and practices of the American avant-garde communities with which these composers collaborated early in their careers. -

Download File

Noise, Sound and Objecthood: The Politics of Representation in the Musical Avant-Garde Alexander Hall Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Alexander Hall All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Noise, Sound and Objecthood: The Politics of Representation in the Musical Avant-Garde Alexander Hall This essay offers both a historical analysis of twentieth century avant-garde practices relating to representation in music, and a prescriptive model for contemporary methods of composition. I address the taxonomy problem in classical music, clarifying the ontological divide identified by German musicologist Michael Rebhahn Contemporary Classical music and New Music. I demonstrate how neoliberalism has developed a Global Style (Foster 2012) of "Light Modernity,” evident in both contemporary architecture and music alike. The central problem facing composition today is the fetishization of materials, ultimately derived from music's refusal to allow the question of representation to be addressed. I argue that composers have largely sought to define noise as sound-in-itself, eliminating the possibilities of representation in the process. Proposing instead that composers should strive to tackle representation head-on in the 21st century, I show how Jacques Rancière provides a model in which noise and sound—representation and abstraction—function in a conjoined, yet non-homogenized aesthetic regime. Governed by what he calls the "pensiveness of the image,” it allows for a renewed art form that rejects repetition and neoliberalism, re-connecting to the spirit of the avant-garde without slavishly echoing either its outmoded aesthetics or dogmatic philosophies. -

A Sweeter Music Preben Antonsen (B.1991) Dar Al-Harb: House of War * Polansky (B’Midbar) No

Cal Performances Presents Program Sunday, January 25, 2009, 3pm The Residents drum no fife (Why We Need War) * Hertz Hall Polansky (B’midbar) No. 6 * A Sweeter Music Preben Antonsen (b.1991) Dar al-Harb: House of War * Polansky (B’midbar) No. 14 * Sarah Cahill, piano Mamoru Fujieda (b.1952) The Olive Branch Speaks John Sanborn, video Terry Riley (b.1935) Be Kind to One Another (Rag) * Commissioned by Stephen B. Hahn and Mary Jane Beddow. PROGRAM * World Premiere Peter Garland (b.1952) After the Wars (excerpts) * Sarah Cahill would like to thank the following individuals: 1. “The nation is ruined, but mountains and Dorothy Cahill, Robert Cole, Miranda Sanborn, Liz and Greg Lutz, Robert Bielecki, rivers remain” (Tu Fu) Margaret Dorfman, Steve Hahn and Mary Jane Beddow, Jerry Kuderna, Paul Dresher, 2. “Summer grass/all that remains/ Joshua Raoul Brody, Skip Sweeney, Bonnie Hughes, Dave Jones Design, Margaret Cromwell, of young warriors’ dreams” (Basho) Joseph Copley and, most of all, John Sanborn, the collaborator and partner of my dreams. Larry Polansky (b.1953) (B’midbar) No. 1 * Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Frederic Rzewski (b.1938) Peace Dances * Commissioned by Robert Bielecki. Polansky (B’midbar) No. 17 * Education & Community Event Yoko Ono (b.1933) Toning * Composers Forum: The Music of Peace: Can Music Be Political? Friday, January 23, 2009, 6–7:30pm Jerome Kitzke (b.1955) There Is a Field * Wheeler Auditorium 1. I Sarah Cahill and several of the commissioned composers discuss the intersection 2. Look Down Fair Moon of politics and music, especially in works without text, and what it means to write 3. -

Transcendentalist Sympathies: a Contextual Study of <I>The Wound

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 11-2020 Transcendentalist Sympathies: A Contextual Study of The Wound- Dresser Jared Hiscock University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Commons Hiscock, Jared, "Transcendentalist Sympathies: A Contextual Study of The Wound-Dresser" (2020). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 151. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/151 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TRANSCENDENTALIST SYMPATHIES: A CONTEXTUAL STUDY OF THE WOUND-DRESSER by Jared Schuyler Hiscock A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor William Shomos Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2020 TRANSCENDENTALIST SYMPATHIES: A CONTEXTUAL STUDY OF THE WOUND-DRESSER Jared Schuyler Hiscock, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2020 Advisor: William Shomos My document takes as its subject The Wound-Dresser by American composer John Coolidge Adams (b. 1947). Published in 1988, this twenty minute work for baritone voice and orchestra remains Adams’s sole contribution to the non-operatic solo voice repertoire. In The Wound-Dresser Adams grapples with the historical churning of his own times by looking to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Charles Ives.