The Compelling Act of Creature Collection in Pokémon, Ni No Kuni, Shin Megami Tensei, and World of Warcraft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for Fiscal Year Ended March 2013 (Briefing Date: 4/25/2013) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2009 FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 Net sales 1,838,622 1,434,365 1,014,345 647,652 635,422 Cost of sales 1,044,981 859,131 626,379 493,997 495,068 Gross profit 793,641 575,234 387,965 153,654 140,354 (Gross profit ratio) (43.2%) (40.1%) (38.2%) (23.7%) (22.1%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 238,378 218,666 216,889 190,975 176,764 Operating income 555,263 356,567 171,076 -37,320 -36,410 (Operating income ratio) (30.2%) (24.9%) (16.9%) (-5.8%) (-5.7%) Non-operating income 32,159 11,082 8,602 9,825 48,485 (of which foreign exchange gains) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (39,506) Non-operating expenses 138,727 3,325 51,577 33,368 1,592 (of which foreign exchange losses) (133,908) (204) (49,429) (27,768) ( - ) Ordinary income 448,695 364,324 128,101 -60,863 10,482 (Ordinary income ratio) (24.4%) (25.4%) (12.6%) (-9.4%) (1.6%) Extraordinary income 339 5,399 186 84 2,957 Extraordinary loss 902 2,282 353 98 3,243 Income before income taxes and minority interests 448,132 367,442 127,934 -60,877 10,197 Income taxes 169,134 138,896 50,262 -17,659 3,029 Income before minority interests - - 77,671 -43,217 7,168 Minority interests in income -91 -89 50 -13 68 Net income 279,089 228,635 77,621 -43,204 7,099 (Net income ratio) (15.2%) (15.9%) (7.7%) (-6.7%) (1.1%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Julius Eastman: the Sonority of Blackness Otherwise

Julius Eastman: The Sonority of Blackness Otherwise Isaac Alexandre Jean-Francois The composer and singer Julius Dunbar Eastman (1940-1990) was a dy- namic polymath whose skill seemed to ebb and flow through antagonism, exception, and isolation. In pushing boundaries and taking risks, Eastman encountered difficulty and rejection in part due to his provocative genius. He was born in New York City, but soon after, his mother Frances felt that the city was unsafe and relocated Julius and his brother Gerry to Ithaca, New York.1 This early moment of movement in Eastman’s life is significant because of the ways in which flight operated as a constitutive feature in his own experience. Movement to a “safer” place, especially to a predomi- nantly white area of New York, made it more difficult for Eastman to ex- ist—to breathe. The movement from a more diverse city space to a safer home environ- ment made it easier for Eastman to take private lessons in classical piano but made it more complicated for him to find embodied identification with other black or queer people. 2 Movement, and attention to the sonic remnants of gesture and flight, are part of an expansive history of black people and journey. It remains dif- ficult for a black person to occupy the static position of composer (as op- posed to vocalist or performer) in the discipline of classical music.3 In this vein, Eastman was often recognized and accepted in performance spaces as a vocalist or pianist, but not a composer.4 George Walker, the Pulitzer- Prize winning composer and performer, shares a poignant reflection on the troubled status of race and classical music reception: In 1987 he stated, “I’ve benefited from being a Black composer in the sense that when there are symposiums given of music by Black composers, I would get perfor- mances by orchestras that otherwise would not have done the works. -

Sega Sammy Holdings Integrated Report 2019

SEGA SAMMY HOLDINGS INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Challenges & Initiatives Since fiscal year ended March 2018 (fiscal year 2018), the SEGA SAMMY Group has been advancing measures in accordance with the Road to 2020 medium-term management strategy. In fiscal year ended March 2019 (fiscal year 2019), the second year of the strategy, the Group recorded results below initial targets for the second consecutive fiscal year. As for fiscal year ending March 2020 (fiscal year 2020), the strategy’s final fiscal year, we do not expect to reach performance targets, which were an operating income margin of at least 15% and ROA of at least 5%. The aim of INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 is to explain to stakeholders the challenges that emerged while pursuing Road to 2020 and the initiatives we are taking in response. Rapidly and unwaveringly, we will implement initiatives to overcome challenges identified in light of feedback from shareholders, investors, and other stakeholders. INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 1 Introduction Cultural Inheritance Innovative DNA The headquarters of SEGA shortly after its foundation This was the birthplace of milestone innovations. Company credo: “Creation is Life” SEGA A Host of World and Industry Firsts Consistently Innovative In 1960, we brought to market the first made-in-Japan jukebox, SEGA 1000. After entering the home video game console market in the 1980s, The product name was based on an abbreviation of the company’s SEGA remained an innovator. Representative examples of this innova- name at the time: Service Games Japan. Moreover, this is the origin of tiveness include the first domestically produced handheld game the company name “SEGA.” terminal with a color liquid crystal display (LCD) and Dreamcast, which In 1966, the periscope game Periscope became a worldwide hit. -

A Nintendo 3DS™ XL Or Nintendo 3DS™

Claim a FREE download of if you register ™ a Nintendo 3DS XL ™ or Nintendo 3DS and one of these 15 games: or + Registration open between November 27th 2013 and January 13th 2014. How it works: 1 2 3 Register a Nintendo 3DS XL or Nintendo 3DS system and one of 15 eligible games Log in to Club Nintendo Use your download code at www.club-nintendo.com by 22:59 (UK time) on January 13th 2014. 24 hours later and in Nintendo eShop check the promotional banners before 22:59 (UK time) Eligible games: for your free download code on March 13th, 2014 • Mario & Luigi™: Dream Team Bros. • Sonic Lost World™ to download ™ • Animal Crossing™: New Leaf • Monster Hunter™ 3 Ultimate SUPER MARIO 3D LAND for free! • The Legend of Zelda™: • Pokémon™ X A Link Between Worlds • Pokémon™ Y ™ • Donkey Kong Country Returns 3D • Bravely Default™ ™ • Fire Emblem : Awakening • New Super Mario Bros.™ 2 ™ • Luigi’s Mansion 2 • Mario Kart™ 7 ® • LEGO CITY Undercover: • Professor Layton The Chase Begins and the Azran Legacy™ Please note: Club Nintendo Terms and Conditions apply. For the use of Nintendo eShop the acceptance of the Nintendo 3DS Service User Agreement and Privacy Policy is required. You must have registered two products: (i) a Nintendo 3DS or Nintendo 3DS XL system (European version; Nintendo 2DS excluded) and (ii) one out of fi fteen eligible games in Club Nintendo at www.club-nintendo.com between 27th November 2013, 15:01 UK time and 13th January 2014, 22:59 UK time. Any packaged or downloadable version of eligible software is eligible for this promotion. -

Poképark™ Wii: Pikachus Großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING Ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR

PRODUKTNAME PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR. 2129140 EAN-NR. 0045496 368982 RELEASE 09.07.2010 PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer Das beliebteste Pokémon Pikachu sorgt wieder einmal für großen Spaß: bei seinem ersten Wii Action-Abenteuer. Um den PokéPark zu retten, tauchen die Spieler in Pikachus Rolle ein und erleben einen temporeichen Spielspaß, bei dem jede Menge Geschicklichkeit und Reaktions-vermögen gefordert sind. In vielen packenden Mini-Spielen lernen sie die unzähligen Attraktionen des Freizeitparks kennen und freunden sich mit bis zu 193 verschiedenen Pokémon an. Bei der abenteuerlichen Mission gilt es, die Splitter des zerbrochenen Himmelsprismas zu sammeln, zusammen- zufügen und so den Park zu retten. Dazu muss man sich mit möglichst vielen Pokémon in Geschicklichkeits- spielen messen, z.B. beim Zweikampf oder Hindernislauf. Nur wenn die Spieler gewinnen, werden die Pokémon ihre Freunde. Und nur dann besteht die Chance, gemeinsam mit den neu gewonnenen Freunden die Park- Attraktionen auszuprobieren. Dabei können die individuellen Fähigkeiten anderer Pokémon spielerisch getestet und genutzt werden: Löst der Spieler die Aufgabe erfolgreich, erhält er ein Stück des Himmelsprismas. Ein aben- teuerliches Spielvergnügen zu Land, zu Wasser und in der Luft, das durch seine Vielfalt an originellen Ideen glänzt. Weitere Informationen fi nden Sie unter: www.nintendo.de © 2010 Pokémon. © 1995-2010 Nintendo/Creatures Inc. /GAME FREAK inc. TM, ® AND THE Wii LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. Developed by Creatures Inc. © 2010 NINTENDO. wii.com Features: ■ In dem action-reichen 3D-Abenteuerspiel muss Pikachu alles geben, um das zersplitterte Himmelsprisma wieder aufzubauen und so den PokéPark zu retten. -

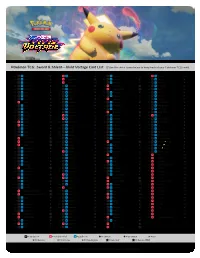

Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List

Pokémon TCG: Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List Use the check boxes below to keep track of your Pokémon TCG cards! 001 Weedle ● 048 Zapdos ★H 095 Lycanroc ★ 142 Tornadus ★H 002 Kakuna ◆ 049 Ampharos V 096 Mudbray ● 143 Pikipek ● 003 Beedrill ★ 050 Raikou ★A 097 Mudsdale ★ 144 Trumbeak ◆ 004 Exeggcute ● 051 Electrike ● 098 Coalossal V 145 Toucannon ★ 005 Exeggutor ★ 052 Manectric ★ 099 Coalossal VMAX X 146 Allister ◆ 006 Yanma ● 053 Blitzle ● 100 Clobbopus ● 147 Bea ◆ 007 Yanmega ★ 054 Zebstrika ◆ 101 Grapploct ★ 148 Beauty ◆ 008 Pineco ● 055 Joltik ● 102 Zamazenta ★A 149 Cara Liss ◆ 009 Celebi ★A 056 Galvantula ◆ 103 Poochyena ● 150 Circhester Bath ◆ 010 Seedot ● 057 Tynamo ● 104 Mightyena ◆ 151 Drone Rotom ◆ 011 Nuzleaf ◆ 058 Eelektrik ◆ 105 Sableye ◆ 152 Hero’s Medal ◆ 012 Shiftry ★ 059 Eelektross ★ 106 Drapion V 153 League Staff ◆ 013 Nincada ● 060 Zekrom ★H 107 Sandile ● 154 Leon ★H 014 Ninjask ★ 061 Zeraora ★H 108 Krokorok ◆ 155 Memory Capsule ◆ 015 Shaymin ★H 062 Pincurchin ◆ 109 Krookodile ★ 156 Moomoo Cheese ◆ 016 Genesect ★H 063 Clefairy ● 110 Trubbish ● 157 Nessa ◆ 017 Skiddo ● 064 Clefable ★ 111 Garbodor ★ 158 Opal ◆ 018 Gogoat ◆ 065 Girafarig ◆ 112 Galarian Meowth ● 159 Rocky Helmet ◆ 019 Dhelmise ◆ 066 Shedinja ★ 113 Galarian Perrserker ★ 160 Telescopic Sight ◆ 020 Orbeetle V 067 Shuppet ● 114 Forretress ★ 161 Wyndon Stadium ◆ 021 Orbeetle VMAX X 068 Banette ★ 115 Steelix V 162 Aromatic Energy ◆ 022 Zarude V 069 Duskull ● 116 Beldum ● 163 Coating Energy ◆ 023 Charmander ● 070 Dusclops ◆ 117 Metang ◆ 164 Stone Energy ◆ -

Pokémon – 25 Year Anniversary

25 years since Created Many people assume that Ishihara (CEO of Pokémon) is the actual creator Satoshi Tajiri as he makes all the public appearances. Tajiri rarely makes public appearances as he has Asperger's syn- drome and this affects his social abilities Satoshi was obsessed with video games and used to play the in the arcades and almost didn't graduate from High School. He spent so much time in his local arcade that he was given his own ‘Space Invaders’ machine. AK 02/2021 Tajiri did a two year technical degree programme at the Tokyo National College of Technology At 17 years of age, Tajiri started a video games magazine called ‘Game Freak’ which was initially handwritten and stapled together . The legendary Ken Sugimori (Pokémon illustrator) became involved with the magazine after coming across it at a local comic shop. Before the release of Pokémon ‘Red and Green’, Ta- jiri directed two games that were published by two of Nintendos biggest rivals, Sony and Sega. Tajiri directed ‘Smart Ball’ for Super Nintendo which was published by Sony and ‘Pulseman’ for the Sega Gen- esis which was published by Sega. By the time the development on Pokémon ‘Red and Green’ began, the whole process from start to finish was ex- tremely rigorous. The games took six years to complete and nearly caused ‘Game Freak’ to go bankrupt. They barely had enough money to pay their employees, with five of them quitting. Tajiri was so dedicated he did not give himself a salary and was supported by his fa- thers income. -

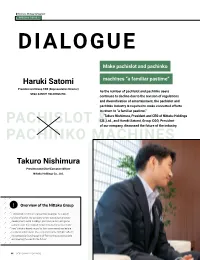

Make Pachislot and Pachinko Machines

Business Strategy by Segment SPECIAL TOPIC 1 DIALOGUE Make pachislot and pachinko machines “a familiar pastime” Haruki Satomi President and Group COO (Representative Director) As the number of pachislot and pachinko users SEGA SAMMY HOLDINGS INC. continues to decline due to the revision of regulations and diversification of entertainment, the pachislot and pachinko industry is required to make concerted efforts to return to “a familiar pastime.” Takuro Nishimura, President and CEO of Nittaku Holdings CO., Ltd., and Haruki Satomi, Group COO, President of our company, discussed the future of the industry. Takuro Nishimura President and Chief Executive Officer Nittaku Holdings Co., Ltd. Overview of the Nittaku Group Established in 1965 as a real estate developer. As a result of diversification, the company is now operating real estate development, rental buildings, pachinko parlors, and game centers under the motto of “Urban leisure and service indus- tries” which is based on profits from commercial real estate located in urban areas. The company’s name “Nittaku” reflects the company’s founding spirit of “Reinventing ourselves daily and opening the way for the future.” 44 SEGA SAMMY HOLDINGS Pachislot and Entertainment Resort Pachinko Machines Contents To make pachislot and pachinko an enjoyable At its peak in the early 1990s, more than 20 years ago, pachislot and and familiar entertainment regardless of past pachinko machines were said to have about 30 million users. However, the number has now fallen to less than about 10 million. In the past, Pachinko developed amid the chaos of the postwar entertainment had limited options, such as movies, travel, and pachinko Nishimura era, and during the period of rapid economic growth, parlors, but now there is a wide variety of entertainment and the current it became a familiar form of entertainment. -

Super Smash Bros. Melee from a Casual Game to a Competitive Game

Playing with the script: Super Smash Bros. Melee From a casual game to a competitive game Joeri Taelman 4112334 New Media and Digital Culture Master thesis Supervisor Dr. Stefan Werning Second reader Dr. René Glas 8th of February, 2015 Abstract This thesis studies the interaction between developers and players outside of game design. It does so by using the concept of ‘playing with the script’. René Glas’ Battlefields of Negotiations (2013) studies the interaction between those two stakeholders for a networked game. In Glas’ case of World of Warcraft, it is networked play, meaning that the developer (Blizzard) has control over the game’s servers and thus can implement the results of negotiations by changing the rules continuously. Playing with the script can be seen as an addition to ‘battlefields of negotiation’, and explains the negotiations outside of the game’s structure for a non-networked game and how these negotiations affect the game series’ continuum. Using a frame analysis, this thesis explores the interaction between Nintendo and the players of the game Super Smash Bros. Melee as participatory culture. The latter is possible by going back and forth between the script inscribed in the object by developers and its displacement by the users, in which the community behind the game, ‘the smashers’, transformed the casual nature of the game into a competitive one. 2 Acknowledgments It took a while to realize this New Media and Digital Culture master thesis for Utrecht University. Not only during, but also before the time of writing I have been helped and influenced by a couple of people. -

Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games

arts Article Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games Carme Mangiron Department of Translation, Interpreting and East Asian Studies, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Abstract: Japanese video games have entertained players around the world and played an important role in the video game industry since its origins. In order to export Japanese games overseas, they need to be localized, i.e., they need to be technically, linguistically, and culturally adapted for the territories where they will be sold. This article hopes to shed light onto the current localization practices for Japanese games, their reception in North America, and how users’ feedback can con- tribute to fine-tuning localization strategies. After briefly defining what game localization entails, an overview of the localization practices followed by Japanese developers and publishers is provided. Next, the paper presents three brief case studies of the strategies applied to the localization into English of three renowned Japanese video game sagas set in Japan: Persona (1996–present), Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2005–present), and Yakuza (2005–present). The objective of the paper is to analyze how localization practices for these series have evolved over time by looking at industry perspectives on localization, as well as the target market expectations, in order to examine how the dialogue between industry and consumers occurs. Special attention is given to how players’ feedback impacted on localization practices. A descriptive, participant-oriented, and documentary approach was used to collect information from specialized websites, blogs, and forums regarding localization strategies and the reception of the localized English versions. -

3.1. Trastorno Del Espectro Autista

Grau en Diseño y Producción de Videojuegos VIDEOJUEGOS Y TRASTORNO DEL ESPECTRO AUTISTA: ESTUDIO SOBRE LAS PREFERENCIAS Y HÁBITOS DE ADOLESCENTES CON TRASTORNO DEL ESPECTRO AUTISTA EN RELACIÓN A LOS VIDEOJUEGOS Memoria MERITXELL LARISSA VÁZQUEZ VENTURO TUTOR: CARLOS GONZÁLEZ TARDÓN CURSO 2018-19 Dedicatoria Para todas aquellas valientes personas que lidian con sus dificultades cada día. Agradecimientos Quiero dar las gracias a todos los profesionales que han hecho posible este proyecto y a las personas que me han ayudado y apoyado para seguir adelante con este trabajo. Abstract In this thesis, an investigation is made about adolescents with high-function ASD’s habits and opinions regarding to videogames compared to a control group without this disorder. Before performing the investigation, a bibliographic research of Autism Spectrum Disorder, videogames, their genres and the positive and negative effects has been done. Also it analyzes the main investigations related to ASD and videogames which serves as the basis for the preparation of a survey for the two studied populations. Resumen En este trabajo, se realiza una investigación sobre los hábitos y opiniones que tienen los adolescentes con TEA con escolarización normalizada respecto a los videojuegos comparado con un grupo de control sin dicho trastorno. Antes de realizar la investigación se hizo un estudio bibliográfico del Trastorno del Espectro Autista, los videojuegos, sus géneros y los efectos positivos y negativos. También analiza las principales investigaciones relacionadas entre el TEA y los videojuegos que sirve de base para la elaboración de la encuesta para las poblaciones investigadas. Resum En aquest treball, es realitza una investigació sobre els hàbits i opinions que tenen els adolescents amb TEA amb escolarització normalitzada respecte als videojocs comparat amb un grup de control sense aquest trastorn. -

Friday 12Th March 2021

Inside this week’s edition: Amazing Pangolin Anime Person reviews! around Cambridge Interview with Year 6 teaching Thrilling poetry legend, competition, Mr Drane and much much more…! Monkey takes own selfie! Editor’s note: Welcome back everyone! We have missed you so much. We have said goodbye to some of The Storey members and welcomed some new journalists (Kiki, Sophia and Jasmina), we hope you have all had a wonderful week and we can’t wait to see you again for next week. We hope you all enjoy this week’s edition of The Storey. -Yasmin The Storey Interview with Mr Charles Emogor Friday, 5th March 2021 (11am) on Zoom By Christopher Picture Credit:The Tab(Link on the next page) Would you please tell us more about yourself? My name is Charles Emogor, and I am from Nigeria. I am doing a PhD in Cambridge looking at pangolin ecology. I did my Masters from Oxford and Bachelors in Nigeria. I did an internship with Nigeria programme of the Wildlife Conservation Society which focussed on gorilla conservation. And I love pangolins! What inspired you to focus on pangolins? I remember seeing pangolins on TV when I was your age, around 9 or 10 years old. They are different from all animals – their super long tongues are longer than the length of their bodies! Pangolins stood out for me and the interest and passion just grew. I now pursue it as a career. Please share some interesting facts about pangolins. People thing that pangolins are related to armadillos, but they are actually related more to cats and dogs! They are the only mammals to have scales.