Towards Accessibility of Games: Mechanical Experience, Competence Profiles and Jutsus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Silent Hill Le Moteur De La Terreur

Bernard Perron SILENT HILL le moteur de la terreur Traduit de l’anglais (Canada) par Claire Reach L>P / QUESTIONS THÉORIQUES L’auteur emploie le titre Silent Hill pour désigner l’ensemble de la série. À la mémoire de Shantal Robert, Silent Hill (sans italiques) désigne la ville éponyme. lumière dans l’obscurité Et pour chaque jeu en particulier, les abréviations suivantes : SH1 Silent Hill (PS1), Konami/Konami (1999). SH2 Silent Hill 2 (PS2/PC), Konami/Konami (2001). SH3 Silent Hill 3 (PS2/PC), Konami/Konami (2003). SH4 Silent Hill 4: The Room (PS2/Xbox/PC), Konami/Konami (2004). SH: 0rigins Silent Hill: 0rigins (PSP/PS2), Konami/Konami (2007). SH: Homecoming Silent Hill: Homecoming (PS3/Xbox 360/PC), Double Helix Games/ Konami (2008). SH: Shattered Memories Silent Hill: Shattered Memories (Wii/PS2/PSP), Climax Studios/Konami (2009). SH: Downpour Silent Hill: Downpour (PS3/ Xbox 360), Vatra Games/Konami (2012). INTRODUCTION Le chemin est le but. Proverbe bouddhiste theravada Toute discussion sur Silent Hill débute immanquable- ment par une comparaison avec Resident Evil. Cette série de jeux sur console très populaire de Capcom (1996) ayant été lancée avant le Silent Hill (SH1) (1999) de Konami, elle était et demeure à ce jour la référence obligée. Toutefois, comme le soulignait l’Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine en couver- ture de son numéro de mars 1999, SH1 était « plus qu’un simple clone de Resident Evil 1 ». On a d’abord remarqué les progrès techniques et esthétiques. Les arrière-plans réa listes et pré calculés en 2D de Raccoon City cédaient la place aux environnements en 3D et en temps réel de Silent Hill. -

The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games

The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Katharine Phelps Humanities 497W December 15, 2007 Just remember that my being a woman doesn't make me any less important! --Faris Final Fantasy V 1 The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Female characters, even as a token love interest, have been a mainstay in adventure games ever since Nintendo became a household name. One of the oldest and most famous is the princess of the Super Mario games, whose only role is to be kidnapped and rescued again and again, ad infinitum. Such a character is hardly emblematic of feminism and female empowerment. Yet much has changed in video games since the early 1980s, when Mario was born. Have female characters, too, changed fundamentally? How much has feminism and changing ideas of women in Japan and the US impacted their portrayal in console games? To address these questions, I will discuss three popular female characters in Nintendo adventure game series. By examining the changes in portrayal of these characters through time and new incarnations, I hope to find a kind of evolution of treatment of women and their gender roles. With such a small sample of games, this study cannot be considered definitive of adventure gaming as a whole. But by selecting several long-lasting, iconic female figures, it becomes possible to show a pertinent and specific example of how some of the ideas of women in this medium have changed over time. A premise of this paper is the idea that focusing on characters that are all created within one company can show a clearer line of evolution in the portrayal of the characters, as each heroine had her starting point in the same basic place—within Nintendo. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Embodying the Game

Transcoding Action: Embodying the game Pedro Cardoso & Miguel Carvalhais ID+, Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Porto, Portugal. [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract this performance that is monitored and interpreted by the While playing a video game, the player-machine interaction is not game system, registering very specific data that is solely characterised by constraints determined by which sensors subordinated to the diverse kinds of input devices that are and actuators are embedded in both parties, but also by how their in current use. actions are transcoded. This paper is focused on that transcoding, By operating those input devices the player interacts with on understanding the nuances found in the articulation between the game world. In some games, for the player to be able to the player's and the system's actions, that enable a communication feedback loop to be established through acts of gameplay. This act in the game world, she needs to control an actor, an communication process is established in two directions: 1) player agent that serves as her proxy. This proxy is her actions directed at the system and, 2) system actions aimed at the representation in the game world. It is not necessarily her player. For each of these we propose four modes of transcoding representation in the story of the game. The player’s proxy that portray how the player becomes increasingly embodied in the is the game element she directly controls, and with which system, up to the moment when the player's representation in the she puts her actions into effect. -

A Nintendo 3DS™ XL Or Nintendo 3DS™

Claim a FREE download of if you register ™ a Nintendo 3DS XL ™ or Nintendo 3DS and one of these 15 games: or + Registration open between November 27th 2013 and January 13th 2014. How it works: 1 2 3 Register a Nintendo 3DS XL or Nintendo 3DS system and one of 15 eligible games Log in to Club Nintendo Use your download code at www.club-nintendo.com by 22:59 (UK time) on January 13th 2014. 24 hours later and in Nintendo eShop check the promotional banners before 22:59 (UK time) Eligible games: for your free download code on March 13th, 2014 • Mario & Luigi™: Dream Team Bros. • Sonic Lost World™ to download ™ • Animal Crossing™: New Leaf • Monster Hunter™ 3 Ultimate SUPER MARIO 3D LAND for free! • The Legend of Zelda™: • Pokémon™ X A Link Between Worlds • Pokémon™ Y ™ • Donkey Kong Country Returns 3D • Bravely Default™ ™ • Fire Emblem : Awakening • New Super Mario Bros.™ 2 ™ • Luigi’s Mansion 2 • Mario Kart™ 7 ® • LEGO CITY Undercover: • Professor Layton The Chase Begins and the Azran Legacy™ Please note: Club Nintendo Terms and Conditions apply. For the use of Nintendo eShop the acceptance of the Nintendo 3DS Service User Agreement and Privacy Policy is required. You must have registered two products: (i) a Nintendo 3DS or Nintendo 3DS XL system (European version; Nintendo 2DS excluded) and (ii) one out of fi fteen eligible games in Club Nintendo at www.club-nintendo.com between 27th November 2013, 15:01 UK time and 13th January 2014, 22:59 UK time. Any packaged or downloadable version of eligible software is eligible for this promotion. -

Poképark™ Wii: Pikachus Großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING Ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR

PRODUKTNAME PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer GENRE Action/Adventure USK-RATING ohne Altersbeschränkung SPIELER 1 ARTIKEL-NR. 2129140 EAN-NR. 0045496 368982 RELEASE 09.07.2010 PokéPark™ Wii: Pikachus großes Abenteuer Das beliebteste Pokémon Pikachu sorgt wieder einmal für großen Spaß: bei seinem ersten Wii Action-Abenteuer. Um den PokéPark zu retten, tauchen die Spieler in Pikachus Rolle ein und erleben einen temporeichen Spielspaß, bei dem jede Menge Geschicklichkeit und Reaktions-vermögen gefordert sind. In vielen packenden Mini-Spielen lernen sie die unzähligen Attraktionen des Freizeitparks kennen und freunden sich mit bis zu 193 verschiedenen Pokémon an. Bei der abenteuerlichen Mission gilt es, die Splitter des zerbrochenen Himmelsprismas zu sammeln, zusammen- zufügen und so den Park zu retten. Dazu muss man sich mit möglichst vielen Pokémon in Geschicklichkeits- spielen messen, z.B. beim Zweikampf oder Hindernislauf. Nur wenn die Spieler gewinnen, werden die Pokémon ihre Freunde. Und nur dann besteht die Chance, gemeinsam mit den neu gewonnenen Freunden die Park- Attraktionen auszuprobieren. Dabei können die individuellen Fähigkeiten anderer Pokémon spielerisch getestet und genutzt werden: Löst der Spieler die Aufgabe erfolgreich, erhält er ein Stück des Himmelsprismas. Ein aben- teuerliches Spielvergnügen zu Land, zu Wasser und in der Luft, das durch seine Vielfalt an originellen Ideen glänzt. Weitere Informationen fi nden Sie unter: www.nintendo.de © 2010 Pokémon. © 1995-2010 Nintendo/Creatures Inc. /GAME FREAK inc. TM, ® AND THE Wii LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. Developed by Creatures Inc. © 2010 NINTENDO. wii.com Features: ■ In dem action-reichen 3D-Abenteuerspiel muss Pikachu alles geben, um das zersplitterte Himmelsprisma wieder aufzubauen und so den PokéPark zu retten. -

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2003」Titles on Exhibit Page.1

「TOKYO GAME SHOW 2003」Titles On Exhibit Page.1 Exhibitor Game Title on Exhibit (Japanese) Game Title on Exhibit Genre Platform Price Release date OnlineGame General Area outbreak ラストウィスパー LAST WHISPER Adventure PC ¥6,800 30-May 静寂の風 Seijyaku no kaze Adventure PC ¥4,800 2-May ATLUS CO., LTD. BUSIN 0 BUSIN 0 Roll-Playing PS2 ¥6,800 13-Nov Regular ¥6,800 グローランサー4 GROWLANSER4 Roll-Playing PS2 18-Dec Deluxe ¥9,800 真・女神転生3~NOCTURNE マニアクス SHIN・MEGAMITENSEI 3~NOCTURNE MANIAKUSU Roll-Playing PS2 ¥5,800 Jan-04 九龍妖魔学園紀 KUHRONYOUMAGAKUENKI Other PS2 TBD Next Year 真・女神転生2 SHIN・MEGAMITENSEI 2 Roll-Playing GBA ¥4,800 26-Sep 真・女神転生デビルチルドレン 炎の書 SHIN・MEGAMITENSEI DEBIRUTIRUDOREN HONOWONOSYO Roll-Playing GBA ¥4,800 12-Sep 真・女神転生デビルチルドレン 氷の書 SHIN・MEGAMITENSEI DEBIRUTIRUDOREN KOORINOSYO Roll-Playing GBA ¥4,800 12-Sep 真・女神転生デビルチルドレン メシアライザー SHIN・MEGAMITENSEI Simulation・Roll-Playing GBA TBD Next Year TAKARA CO., LTD. EX人生ゲームⅡ EX JINSEI GAME Ⅱ Board Game PS2 ¥6,800 7-Nov ドリームミックスTV ワールドファイターズ DreamMix TV World Fighters Action PS2/GC TBD December デュエル・マスターズGC(仮) DUEL MASTERS VirtualCardGame GC ¥6,800 19-Dec チョロQHG4 CHORO Q HG4 Racing PS2 ¥6,800 27-Nov トランスフォーマー TRANSFORMERS Action PS2 ¥6,800 30-Oct D・N・ANGEL ~紅の翼~ D・N・ANGEL Adventure PS2 ¥6,800 25-Sep 冒険遊記プラスターワールド 伝説のプラストゲートEX PLUSTERWORLD EX Roll-Playing GBA ¥6,800 4-Dec トランスフォーマーシリーズ TRANSFORMERS Toys on display たいこでポピラ TAIKO DE POPIRA Free trials for visitors / Product Price: ¥5,980 サンダーバードシリーズ THUNDERBIRDS Toys on display KADOKAWA CO., LTD. D.C.P.S~ダ・カーポ~プラスシチュエーション D.C. -

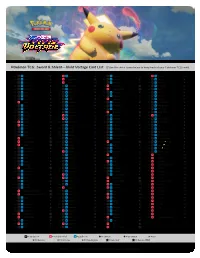

Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List

Pokémon TCG: Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List Use the check boxes below to keep track of your Pokémon TCG cards! 001 Weedle ● 048 Zapdos ★H 095 Lycanroc ★ 142 Tornadus ★H 002 Kakuna ◆ 049 Ampharos V 096 Mudbray ● 143 Pikipek ● 003 Beedrill ★ 050 Raikou ★A 097 Mudsdale ★ 144 Trumbeak ◆ 004 Exeggcute ● 051 Electrike ● 098 Coalossal V 145 Toucannon ★ 005 Exeggutor ★ 052 Manectric ★ 099 Coalossal VMAX X 146 Allister ◆ 006 Yanma ● 053 Blitzle ● 100 Clobbopus ● 147 Bea ◆ 007 Yanmega ★ 054 Zebstrika ◆ 101 Grapploct ★ 148 Beauty ◆ 008 Pineco ● 055 Joltik ● 102 Zamazenta ★A 149 Cara Liss ◆ 009 Celebi ★A 056 Galvantula ◆ 103 Poochyena ● 150 Circhester Bath ◆ 010 Seedot ● 057 Tynamo ● 104 Mightyena ◆ 151 Drone Rotom ◆ 011 Nuzleaf ◆ 058 Eelektrik ◆ 105 Sableye ◆ 152 Hero’s Medal ◆ 012 Shiftry ★ 059 Eelektross ★ 106 Drapion V 153 League Staff ◆ 013 Nincada ● 060 Zekrom ★H 107 Sandile ● 154 Leon ★H 014 Ninjask ★ 061 Zeraora ★H 108 Krokorok ◆ 155 Memory Capsule ◆ 015 Shaymin ★H 062 Pincurchin ◆ 109 Krookodile ★ 156 Moomoo Cheese ◆ 016 Genesect ★H 063 Clefairy ● 110 Trubbish ● 157 Nessa ◆ 017 Skiddo ● 064 Clefable ★ 111 Garbodor ★ 158 Opal ◆ 018 Gogoat ◆ 065 Girafarig ◆ 112 Galarian Meowth ● 159 Rocky Helmet ◆ 019 Dhelmise ◆ 066 Shedinja ★ 113 Galarian Perrserker ★ 160 Telescopic Sight ◆ 020 Orbeetle V 067 Shuppet ● 114 Forretress ★ 161 Wyndon Stadium ◆ 021 Orbeetle VMAX X 068 Banette ★ 115 Steelix V 162 Aromatic Energy ◆ 022 Zarude V 069 Duskull ● 116 Beldum ● 163 Coating Energy ◆ 023 Charmander ● 070 Dusclops ◆ 117 Metang ◆ 164 Stone Energy ◆ -

Game Developers Conference Europe Wrap, New Women’S Group Forms, Licensed to Steal Super Genre Break Out, and More

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS SPEEDTREE RT 1.7 * SPACEPILOT OCTOBER 2005 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>POSTMORTEM >>WALKING THE PLANK >>INNER PRODUCT ART & ARTIFICE IN DANIEL JAMES ON DEBUG? RELEASE? RESIDENT EVIL 4 CASUAL MMO GOLD LET’S DEVELOP! Thanks to our publishers for helping us create a new world of video games. GameTapTM and many of the video game industry’s leading publishers have joined together to create a new world where you can play hundreds of the greatest games right from your broadband-connected PC. It’s gaming freedom like never before. START PLAYING AT GAMETAP.COM TM & © 2005 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. A Time Warner Company. Patent Pending. All Rights Reserved. GTP1-05-116-104_mstrA_v2.indd 1 9/7/05 10:58:02 PM []CONTENTS OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 9 FEATURES 11 TOP 20 PUBLISHERS Who’s the top dog on the publishing block? Ranked by their revenues, the quality of the games they release, developer ratings, and other factors pertinent to serious professionals, our annual Top 20 list calls attention to the definitive movers and shakers in the publishing world. 11 By Tristan Donovan 21 INTERVIEW: A PIRATE’S LIFE What do pirates, cowboys, and massively multiplayer online games have in common? They all have Daniel James on their side. CEO of Three Rings, James’ mission has been to create an addictive MMO (or two) that has the pick-up-put- down rhythm of a casual game. In this interview, James discusses the barriers to distributing and charging for such 21 games, the beauty of the web, and the trouble with executables. -

Nintendo Wii

Nintendo Wii Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Another Code: R - Kioku no Tobira Nintendo Arc Rise Fantasia Marvelous Entertainment Bio Hazard Capcom Bio Hazard: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard 4: Wii Edition: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard Chronicles Value Pack Capcom Bio Hazard Zero Capcom Bio Hazard Zero: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard Zero: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles: Collector's Package Capcom Bio Hazard: The Darkside Chronicles: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Wii Zapper Bundle Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Best Price! Capcom Bio Hazard: The Umbrella Chronicles: Best Price! Reprint Capcom Biohazard: Umbrella Chronicals Capcom Bleach: Versus Crusade Sega Bomberman Hudson Soft Bomberman: Hudson the Best Hudson Soft Captain Rainbow Nintendo Chibi-Robo! (Wii de Asobu) Nintendo Dairantou Smash Brothers X Nintendo Deca Sporta 3 Hudson Disaster: Day of Crisis Nintendo Donkey Kong Returns Nintendo Donkey Kong Taru Jet Race Nintendo Dragon Ball Z: Sparking! Neo Bandai Namco Games Dragon Quest 25th Anniversary Square Enix Dragon Quest Monsters: Battle Road Victory Square Enix Dragon Quest Sword: Kamen no Joou to Kagami no Tou Square Enix Dragon Quest X: Mezameshi Itsutsu no Shuzoku Online Square Enix Earth Seeker Enterbrain -

Design Recommendations for Intelligent Tutoring Systems

Design Recommendations for Intelligent Tutoring Systems Volume 1 Learner Modeling Edited by: Robert Sottilare Arthur Graesser Xiangen Hu Heather Holden A Book in the Adaptive Tutoring Series Copyright © 2013 by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Copyright not claimed on material written by an employee of the U.S. Government. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner, print or electronic, without written permission of the copyright holder. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Army Research Laboratory. Use of trade names or names of commercial sources is for information only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Army Research Laboratory. This publication is intended to provide accurate information regarding the subject matter addressed herein. The information in this publication is subject to change at any time without notice. The U.S. Army Research Laboratory, nor the authors of the publication, makes any guarantees or warranties concerning the information contained herein. Printed in the United States of America First Printing, July 2013 First Printing (errata addressed), August 2013 U.S. Army Research Laboratory Human Research & Engineering Directorate SFC Paul Ray Smith Simulation & Training Technology Center Orlando, Florida International Standard Book Number: 978-0-9893923-0-3 We wish to acknowledge the editing and formatting contributions of Carol Johnson, ARL Dedicated to current and future scientists and developers of adaptive learning technologies CONTENTS Preface i Section I: Fundamentals of Learner Modeling 1 Chapter 1 ‒ A Guide to Understanding Learner Models .........