Julius Caesar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

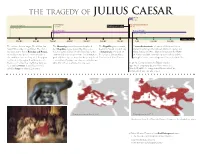

THE TR AGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR Transition 49–27 BC Coriolanus Caesar assassinated Roman Kingdom 494 BC Shakespeare’s play 44 BC 753–509 BC Roman Republic Roman Empire 509–49 BC 27 BC – 293 AD Roman Epochs 700 BC 600 BC 500 BC 400 BC 300 BC 200 BC 100 BC 1 AD 100 AD 200 AD The enforced vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, has The Monarchy is overthrown and replaced The Republic grows corrupt, A second triumvirate is formed of Octavius Caesar twins fathered by the god Mars. The stolen by a Republic, a government by the people, begins to flounder and decay. (Julius Caesar’s great-nephew), Marcus Lepidus, and and abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, headed by two consuls elected annually by the A triumvirate is formed of Mark Antony. In 27 BC, Mark Antony loses the Battle are fed by a woodpecker and nursed by a citizens and advised by a senate. A constitution Pompey the Great, Marcus of Actium and kills himself, Lepidus is exiled, and the she-wolf in a cave, the Lupercal. They grow gradually develops, centered on the principles of Crassus, and Julius Caesar. young Caesar becomes Augustus Caesar, Exalted One. up, found a city, argue, then Romulus kills a separation of powers and checks and balances. Remus and names the city Rome. OR it was All public offices are limited to one year. In 49 BC, Caesar crosses the Rubicon and is founded by Aeneas about this time. It is appointed temporary dictator three times; on ruled by kings for almost 250 years. -

Aguirre-Santiago-Thesis-2013.Pdf

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE SIC SEMPER TYRANNIS: TYRANNICIDE AND VIOLENCE AS POLITICAL TOOLS IN REPUBLICAN ROME A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in History By Santiago Aguirre May 2013 The thesis of Santiago Aguirre is approved: ________________________ ______________ Thomas W. Devine, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Patricia Juarez-Dappe, Ph.D. Date ________________________ ______________ Frank L. Vatai, Ph.D, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii DEDICATION For my mother and father, who brought me to this country at the age of three and have provided me with love and guidance ever since. From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank you for all the sacrifices that you have made to help me fulfill my dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Frank L. Vatai. He helped me re-discover my love for Ancient Greek and Roman history, both through the various courses I took with him, and the wonderful opportunity he gave me to T.A. his course on Ancient Greece. The idea to write this thesis paper, after all, was first sparked when I took Dr. Vatai’s course on the Late Roman Republic, since it made me want to go back and re-read Livy. I also want to thank Dr. Patricia Juarez-Dappe, who gave me the opportunity to read the abstract of one of my papers in the Southwestern Social Science Association conference in the spring of 2012, and later invited me to T.A. one of her courses. -

Julius Caesar

Working Paper CEsA CSG 168/2018 ANCIENT ROMAN POLITICS – JULIUS CAESAR Maria SOUSA GALITO Abstract Julius Caesar (JC) survived two civil wars: first, leaded by Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius; and second by himself and Pompeius Magnus. Until he was stabbed to death, at a senate session, in the Ides of March of 44 BC. JC has always been loved or hated, since he was alive and throughout History. He was a war hero, as many others. He was a patrician, among many. He was a roman Dictator, but not the only one. So what did he do exactly to get all this attention? Why did he stand out so much from the crowd? What did he represent? JC was a front-runner of his time, not a modern leader of the XXI century; and there are things not accepted today that were considered courageous or even extraordinary achievements back then. This text tries to explain why it’s important to focus on the man; on his life achievements before becoming the most powerful man in Rome; and why he stood out from every other man. Keywords Caesar, Politics, Military, Religion, Assassination. Sumário Júlio César (JC) sobreviveu a duas guerras civis: primeiro, lideradas por Cornélio Sula e Caio Mário; e depois por ele e Pompeius Magnus. Até ser esfaqueado numa sessão do senado nos Idos de Março de 44 AC. JC foi sempre amado ou odiado, quando ainda era vivo e ao longo da História. Ele foi um herói de guerra, como outros. Ele era um patrício, entre muitos. Ele foi um ditador romano, mas não o único. -

Roman History the LEGENDARY PERIOD of the KINGS (753

Roman History THE LEGENDARY PERIOD OF THE KINGS (753 - 510 B.C.) Rome was said to have been founded by Latin colonists from Alba Longa, a nearby city in ancient Latium. The legendary date of the founding was 753 B.C.; it was ascribed to Romulus and Remus, the twin sons of the daughter of the king of Alba Longa. Later legend carried the ancestry of the Romans back to the Trojans and their leader Aeneas, whose son Ascanius, or Iulus, was the founder and first king of Alba Longa. The tales concerning Romulus’s rule, notably the rape of the Sabine women and the war with the Sabines, point to an early infiltration of Sabine peoples or to a union of Latin and Sabine elements at the beginning. The three tribes that appear in the legend of Romulus as the parts of the new commonwealth suggest that Rome arose from the amalgamation of three stocks, thought to be Latin, Sabine, and Etruscan. The seven kings of the regal period begin with Romulus, from 753 to 715 B.C.; Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, from 534 to 510 B.C., the seventh and last king, whose tyrannical rule was overthrown when his son ravished Lucretia, the wife of a kinsman. Tarquinius was banished, and attempts by Etruscan or Latin cities to reinstate him on the throne at Rome were unavailing. Although the names, dates, and events of the regal period are considered as belonging to the realm of fiction and myth rather than to that of factual history, certain facts seem well attested: the existence of an early rule by kings; the growth of the city and its struggles with neighboring peoples; the conquest of Rome by Etruria and the establishment of a dynasty of Etruscan princes, symbolized by the rule of the Tarquins; the overthrow of this alien control; and the abolition of the kingship. -

Roma'nin Kaderini Çizmiş Bir Ailenin

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANA BİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ CORNELII SCIPIONES: ROMA’NIN KADERİNİ ÇİZMİŞ BİR AİLENİN TARİHİ VE MİRASI Mehmet Esat Özer 2501151298 Tez Danışmanı Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Gürkan Ergin İSTANBUL-2019 ÖZ CORNELII SCIPIONES: ROMA’NIN KADERİNİ ÇİZMİŞ BİR AİLENİN TARİHİ VE MİRASI MEHMET ESAT ÖZER Scipio ailesinin tarihi neredeyse Roma Cumhuriyeti’nin kendisi kadar eskidir. Scipio’lar Roma Cumhuriyeti’nde yüksek memuriyet görevlerinde en sık yer almış ailelerinden biri olup yükselişleri etkileyicidir. Roma’nın bir varoluş mücadelesi verdiği Veii Savaşları’ndan yükselişe geçtiği Kartaca Savaşları’na Roma Cumhuriyet tarihinin en kritik anlarında sahne alarak Roma’nın Akdeniz Dünyası’nın egemen gücü olmasına katkıda bulunmuşlardır. Aile özellikle Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus gibi isimlerin elde ettiği başarılarla Roma aristokrasisinde ön plana çıkarak Roma’nın siyasi ve askeri tarihinin önemli olaylarında başrol oynamıştır. Bu tezde Scipio ailesi antik yazarların eserleri ve arkeolojik veriler ışığında incelenerek ailenin geçmişi; siyasi, sosyal, kültürel alanlardaki faaliyetleriyle katkıları ve Roma’nın emperyal bir devlete dönüşmesindeki etkileri değerlendirilecektir. Konunun kapsamı sadece ailenin Roma Cumhuriyet tarihindeki yeriyle sınırlı kalmayıp sonraki dönemlerde de zamanın şartlarına göre nasıl algılandığına da değinilecektir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Cornelii Scipiones, Scipio, Roma Cumhuriyeti, Aristokrasi, Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus, Kartaca, Emperyal. -

Anglo-Saxon Constitutional History

Outline Wed., 8 Sep. ROMAN LAW INTRODUCTION, REPUBLICAN CONSTITUTIONAL OUTLINE I. INTRODUCTION 1. If you don’t know Latin, that’s just fine, but we are going to ask you to learn about 100 Latin words because you should not translate technical legal terms from one language to another. 2. Please fill out the Sign-up sheets that are included in the syllabus and were sent to you by email. When you click on ‘Submit’, they will be sent to us by email. We need these before the class next week because we are going to make up the small groups on the basis of them. 3. Why study Roman law? a. Diachronic reasons b. Synchronic reasons 4. These reasons lead to the four parts of the course (roughly three weeks each) a. External history – chronology, institutions, procedure, sources of law. b. Internal history – a survey of Roman private law based on the institutional treatises of Gaius (c. 160 AD) and, to a lesser extent, that of Justinian (533 AD) c. The XII Tables of c. 450 BC d. Juristic method – selected topics in society and ideas as seen through the eyes the jurists from roughly 100 BC to roughly 240 AD 5. Mechanics a. The Syllabus b. The Readings c. The Class Outlines d. Requirements for Credit i. Post a comment or a question about the assignment before each class. ii. Write a five-page paper on on one of the topics in the third or fourth parts of the course, drafts to be turned into us the day of the class and rewritten on the basis of the class and our comments iii. -

Sex in the Ancient World from a to Z the Ancient World from a to Z

SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z What were the ancient fashions in men’s shoes? How did you cook a tunny or spice a dormouse? What was the daily wage of a Syracusan builder? What did Romans use for contraception? This new Routledge series will provide the answers to such questions, which are often overlooked by standard reference works. Volumes will cover key topics in ancient culture and society—from food, sex and sport to money, dress and domestic life. Each author will be an acknowledged expert in their field, offering readers vivid, immediate and academically sound insights into the fascinating details of daily life in antiquity. The main focus will be on Greece and Rome, though some volumes will also encompass Egypt and the Near East. The series will be suitable both as background for those studying classical subjects and as enjoyable reading for anyone with an interest in the ancient world. Already published: Food in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Dalby Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z Mark Golden Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z John G.Younger Forthcoming titles: Birds in the Ancient World from A to Z Geoffrey Arnott Money in the Ancient World from A to Z Andrew Meadows Domestic Life in the Ancient World from A to Z Ruth Westgate and Kate Gilliver Dress in the Ancient World from A to Z Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones et al. SEX IN THE ANCIENT WORLD FROM A TO Z John G.Younger LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2006. -

Erfolgreich in Etrurien, Glücklos in Rom

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Mitglieder der catilinarischen Verschwörung“ Verfasser Michael Wengraf angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im November 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 310 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Alte Geschichte Betreuerin / Betreuer: ao. Univ.- Prof. Dr. Herbert Heftner 2 Für meine Eltern 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis ............................................................................................................ 4 1. Die Quellenlage ..................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Die späte Republik (Latein) ................................................................................................. 9 1.2 Die julisch-claudische Kaiserzeit (Latein) ........................................................................... 9 1.3 Die flavianische Kaiserzeit (Latein) ................................................................................... 10 1.4 Die Adoptivkaiser (Latein) ................................................................................................. 11 1.5 Die Adoptivkaiser (Griechisch) ......................................................................................... 11 1.6 Die Severer (Griechisch) .................................................................................................... 12 1.7 Die Spätantike (Latein) ..................................................................................................... -

Imperium Romanum - Scenarios © 2018 Decision Games

Imperium© 2018 DecisionRomanum Games - Scenarios 1 BX-U_ImperiumRom3-Scenarios_V4F.indd 1 10/10/18 10:38 AM # of Players No. Name Dates Period Max/Min/Opt. Page Number 1 The Gallic Revolt * Nov. 53 to Oct. 52 BC 1 2 4 2 Pompey vs. the Pirates * (1) Apr. to Oct. 67 BC 1 2 5 3 Marius vs. Sulla July 88 to Jan. 82 BC 1 4/3/3 6 4 The Great Mithridatic War June 75 to Oct. 72 BC 1 3 8 5 Crisis of the First Triumvirate Feb. 55 to Sep. 52 BC 1 6/4/5 10 6 Caesar vs. Pompey Nov. 50 to Aug. 48 BC 2 2 12 7 Caesar vs. the Sons of Pompey July 47 to May 45 BC 2 2 13 8 The Triumvirs vs. the Assassins Dec. 43 to Dec. 42 BC 2 2 15 9 Crisis of the Second Triumvirate Jan. 38 to Sep. 35 BC 2 5/3/4 16 10 Octavian vs. Antony & Cleopatra Apr. 32 to Aug. 30 BC 2 2 18 11 The Revolt of Herod Agrippa (1) AD March 45-?? 3 2 19 12 The Year of the Four Emperors AD Jan. 69 to Dec. 69 3 4/3/3 20 13 Trajan’s Conquest of Dacia * (1) AD Jan. 101 to Nov. 102 3 2 22 14 Trajan’s Parthian War (1) AD Jan. 115 to Aug. 117 3 2 23 15 Avidius Cassius vs. Pompeianus (1) AD June 175-?? 3 2 25 16 Septimius Severus vs. Pescennius Niger vs. AD Apr. 193 to Feb. -

Cricat-3.4.1 Gamebook.Pages

THE CRISIS OF CATILINE ROME, 63 BCE GAME BOOKLET Bret Mulligan VERSION 3.4.3 (August 2017) THIS MANUSCRIPT IS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT AS PART OF THE “REACTING TO THE PAST” INITIATIVE OFFERED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF BARNARD COLLEGE. Reacting to the Past™ and its materials are copyrighted. Instructors seeking to reproduce these materials for educational purposes must request permission via email to [email protected] and [email protected]. Permission requests should indicate the following: (1) Name of Instructor, Institution, and Course in which the materials will be used; (2) Number of copies to be reproduced; and (3) If the printed booklets will be distributed to students at no cost or at cost. For additional information about the “Reacting to the Past” Series, please visit http:// barnard.edu/reacting. Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Necessity of Action 2 Rome in 63 BCE 3 A Tense Night in Rome (Historical Vignette) 4 How to React to the Past 11 Your Speech 15 Historical Context 19 The Growth of Rome and its Empire 19 Rome’s Empire in the First Century BCE 22 The Crises of the Republic 24 A Note on the Crisis of 64-63 BCE 34 Roles & Factions 35 Roles by Faction 37 Non-Voting Roles 37 Album Senatorum 38 Public Biographies 39 Rules & Traditions of the Roman Senate 45 Special Actions and Gambits 48 Map of Roman Italy 51 List of Primary Sources 52 Cicero — First Oration Against Catiline (In Catilinam I) 54 Appendix 1: Glossary of Roman Terms 61 Appendix 2: History of the Senatus Consultum Ultimum 63 Appendix 3: Roman Virtues 65 Appendix 4: Sample Speech (Capito’s Full Speech from “A Tense Night”) 68 Acknowledgements 72 !1 It is the year when Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida are consuls. -

Saint Ignatius College Prep Saint Ignatius Model United Nations

! Saint Ignatius College Prep SIMUN XVI Saint Ignatius Model United Nations ! Chicago, IL November 4, 2017 ! Julius Caesar’s Civil War Table of Contents Letter from the Chair 2 Important Notes 3 List of Positions 4 Introduction to the Roman Republic 5 Introduction to Julius Caesar 7 Topic A 8 Topic B 11 Bibliography 13 “Ανερριφθω κυβος” Figure 1 (top): A map of the Roman Republic in 49 B.C. showing the territory of Caesar and Pompey Figure 2 (bottom): A map showing provinces and client states !1 Salvete Delegati, My name is Don Harmon and I look forward to being your chair for Julius Caesar’s Civil War at SIMUN XVI. I am a senior at Ignatius, a four-year member of SIMUN, and an Exec Board member of the Saint Ignatius Classics Club, dedicated to the Greek and Latin languages and civilizations. In addition to Classics and MUN, I am interested in history, social sciences, and philosophy, and am also an avid guitar player. This is my first time chairing my own committee, and I’m so excited to see what you all will bring to such a fascinating historical cabinet, full of intricacies and intrigue. One reason I find Julius Caesar’s cabinet in the Civil War to make such a phenomenal MUN committee is the variety and memorability of the characters. Reading about Caesar’s time, one will encounter so many utterly remarkable figures, from the brilliant to the absurd, whose colorful personalities can shine through even in the few scraps of anecdote that survive to the modern day.