Rome and the Barbarians Part I Professor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valerius Maximus on Vice: a Commentary of Facta Et Dicta

Valerius Maximus on Vice: A Commentary on Facta et Dicta Memorabilia 9.1-11 Jeffrey Murray University of Cape Town Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the School of Languages and Literatures University of Cape Town June 2016 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Abstract The Facta et Dicta Memorabilia of Valerius Maximus, written during the formative stages of the Roman imperial system, survives as a near unique instance of an entire work composed in the genre of Latin exemplary literature. By providing the first detailed historical and historiographical commentary on Book 9 of this prose text – a section of the work dealing principally with vice and immorality – this thesis examines how an author employs material predominantly from the earlier, Republican, period in order to validate the value system which the Romans believed was the basis of their world domination and to justify the reign of the Julio-Claudian family. By detailed analysis of the sources of Valerius’ material, of the way he transforms it within his chosen genre, and of how he frames his exempla, this thesis illuminates the contribution of an often overlooked author to the historiography of the Roman Empire. -

ROMAN POLITICS DURING the JUGURTHINE WAR by PATRICIA EPPERSON WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State

ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR By PATRICIA EPPERSON ,WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1975 SEP Ji ·J75 ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR Thesis Approved: . Dean of the Graduate College 91648 ~31 ii PREFACE The Jugurthine War occurred within the transitional period of Roman politics between the Gracchi and the rise of military dictators~ The era of the Numidian conflict is significant, for during that inter val the equites gained political strength, and the Roman army was transformed into a personal, professional army which no longer served the state, but dedicated itself to its commander. The primary o~jec tive of this study is to illustrate the role that political events in Rome during the Jugurthine War played in transforming the Republic into the Principate. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Neil Hackett, for his patient guidance and scholarly assistance, and to also acknowledge the aid of the other members of my counnittee, Dr. George Jewsbury and Dr. Michael Smith, in preparing my final draft. Important financial aid to my degree came from the Dr. Courtney W. Shropshire Memorial Scholarship. The Muskogee Civitan Club offered my name to the Civitan International Scholarship Selection Committee, and I am grateful for their ass.istance. A note of thanks is given to the staff of the Oklahoma State Uni versity Library, especially Ms. Vicki Withers, for their overall assis tance, particularly in securing material from other libraries. -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

The Manipulation of Fear in Julius Caesar's" Bellum Gallicum."

THE MANIPULATION OF FEAR IN JULIUS CAESAR'S BELLUM GALLICUM by Kristin Slonsky Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Kristin Slonsky, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43525-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43525-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

2012 Njcl Certamen Novice Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Give the case and use of the Latin word for “son” in the following English sentence: Māter ad templum cum fīliō currēbat. ABLATIVE OF ACCOMPANIMENT B1: What are the case and use of the word templum in the same sentence? ACCUSATIVE OF PLACE TO WHICH (prompt on “object of preposition”) B2: What three distinct Latin prepositions are commonly used to express the ablative of place from which? AB / Ā; EX / Ē; DĒ 2. Which of the Greeks at Troy convinced Agamemnon to abandon Philoctetes and also convinced Clytemnestra to send Iphigeneia to Aulis by telling her that she would be the bride of Achilles? ODYSSEUS B1: What enemy did Odysseus convince the Greeks to execute as vengeance for his role in revealing Odysseus’ scheme to stay out of the war? PALAMEDES B2: Odysseus was also adamant that no descendant of Priam should survive the war, and thus insisted that whose infant son Astyanax be thrown from the walls? HECTOR’S 3. What two-word Latin phrase might be found in a document denying a lawyer’s motion because the conclusion did not logically follow from the arguments? NŌN SEQUITUR B1: What three-word Latin phrase might be found on a power-of-attorney document enabling another person to make decisions for a child in place of a parent? IN LOCŌ PARENTIS B2: What two-word Latin phrase is found on legal documents in which the accused does not wish to contest the charges brought against him? NŌLŌ CONTENDERE 4. What famous Roman patrician first distinguished himself while serving as quaestor under Marius, when he succeeded in negotiating the surrender of Jugurtha? (LUCIUS CORNELIUS) SULLA (FELIX) B1: In what year did Sulla hold his first consulship? 88 BC B2: The tribune Sulpicius Rufus stripped Sulla of his command in the war against what Eastern king? MITHRIDATES (IV EUPATOR) 5. -

A Game of Power Courtly Influence on the Decision-Making of Emperor Theodosius II (R

A game of power Courtly influence on the decision-making of emperor Theodosius II (r. 408-450) Research Master Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Dr. L.V. Rutgers Consulting reader: Dr. R. Strootman RMA Ancient, Medieval and Renaissance Studies Utrecht University 16-06-2013 Emma Groeneveld [email protected] 3337707 1 Index Preface ................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 4 1. Court studies ..................................................................................................... 8 2. Theodosius ......................................................................................................20 3. High officials ....................................................................................................25 4. Eunuchs ..........................................................................................................40 5. Royal women ...................................................................................................57 6. Analysis ...........................................................................................................69 Conclusion ...........................................................................................................83 Bibliography.........................................................................................................86 Appendix I. ..........................................................................................................92 -

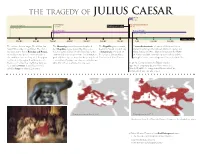

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

THE TR AGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR Transition 49–27 BC Coriolanus Caesar assassinated Roman Kingdom 494 BC Shakespeare’s play 44 BC 753–509 BC Roman Republic Roman Empire 509–49 BC 27 BC – 293 AD Roman Epochs 700 BC 600 BC 500 BC 400 BC 300 BC 200 BC 100 BC 1 AD 100 AD 200 AD The enforced vestal virgin, Rhea Silvia, has The Monarchy is overthrown and replaced The Republic grows corrupt, A second triumvirate is formed of Octavius Caesar twins fathered by the god Mars. The stolen by a Republic, a government by the people, begins to flounder and decay. (Julius Caesar’s great-nephew), Marcus Lepidus, and and abandoned twins, Romulus and Remus, headed by two consuls elected annually by the A triumvirate is formed of Mark Antony. In 27 BC, Mark Antony loses the Battle are fed by a woodpecker and nursed by a citizens and advised by a senate. A constitution Pompey the Great, Marcus of Actium and kills himself, Lepidus is exiled, and the she-wolf in a cave, the Lupercal. They grow gradually develops, centered on the principles of Crassus, and Julius Caesar. young Caesar becomes Augustus Caesar, Exalted One. up, found a city, argue, then Romulus kills a separation of powers and checks and balances. Remus and names the city Rome. OR it was All public offices are limited to one year. In 49 BC, Caesar crosses the Rubicon and is founded by Aeneas about this time. It is appointed temporary dictator three times; on ruled by kings for almost 250 years. -

Caesar and Cleopatra

CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA By George Bernard Shaw ACT I An October night on the Syrian border of Egypt towards the end of the XXXIII Dynasty, in the year 706 by Roman computation, afterwards reckoned by Christian computation as 48 B.C. A great radiance of silver fire, the dawn of a moonlit night, is rising in the east. The stars and the cloudless sky are our own contemporaries, nineteen and a half centuries younger than we know them; but you would not guess that from their appearance. Below them are two notable drawbacks of civilization: a palace, and soldiers. The palace, an old, low, Syrian building of whitened mud, is not so ugly as Buckingham Palace; and the officers in the courtyard are more highly civilized than modern English officers: for example, they do not dig up the corpses of their dead enemies and mutilate them, as we dug up Cromwell and the Mahdi. They are in two groups: one intent on the gambling of their captain Belzanor, a warrior of fifty, who, with his spear on the ground beside his knee, is stooping to throw dice with a sly-looking young Persian recruit; the other gathered about a guardsman who has just finished telling a naughty story (still current in English barracks) at which they are laughing uproariously. They are about a dozen in number, all highly aristocratic young Egyptian guardsmen, handsomely equipped with weapons and armor, very unEnglish in point of not being ashamed of and uncomfortable in their professional dress; on the contrary, rather ostentatiously and arrogantly warlike, as valuing themselves on their military caste. -

Via Popilia E Via Annia

Via Popilia e via Annia http://www.nuovascintilla.com/index.php/terriotorio/cavarzere/16485-v... Settimanale di informazione della diocesi di Chioggia, sede: Rione Duomo 736/a - tel 0415500562 [email protected] Home Temi attuali Chiesa Territorio vita e cultura Contatti Altri settimanali Via Popilia e via Annia Cavarzere e le antiche strade romane Sotto la dominazione romana furono costruite dappertutto magnifiche strade. La costruzione viene riferita tra la seconda guerra Punica e la Cimbrica (201-101 a.C.). Molte percorrevano il territorio di Piove di Sacco, ovvero il territorio della Saccisica (che era a questo riguardo uno tra i più forniti del Padovano) e interessavano anche quello di Cavarzere e di Cona veneziana. Una delle principali strade di cui si è avuta notizia era la via Popilia o Popillia, che da Adria (da dove si congiungeva con Roma) correva in direzione Sud-Nord, probabilmente in linea retta. Fu costruita dal console romano Publius Popillius Lenate, figlio di un certo Quinto (rimasto in carica tra il 132 e il 131 a.C.). Ma c’erano anche altre strade minori. La via Popilia, proveniente da Rimini, attraversava Adria, proseguiva attraverso Cavarzere, il Foresto di Cona, Vallonga di Arzergrande e Sambruson per raggiungere Altino e Aquileia, unendosi alla via Annia. Era chiamata anche Romea, perché si congiungeva con la via Flaminia e portava a Roma. Da Adria si staccavano dalla Popilia delle vie collaterali che la collegavano con Este e Padova (quindi con Altinate e Aquileia). Sembra, in particolare, che la Popilia attraversasse Cavarzere nei pressi dei Dossi Vallieri, passando poi di lato a San Pietro d’Adige, in un sito denominato “Masenile” (in prossimità di Cavanella d’Adige), che trarrebbe così origine da “masegno”, macigno, pietra grigia, non dura quanto il marmo, per selciare (Boezio). -

Alexander Panayotov Phd Thesis

THE JEWS IN THE BALKAN PROVINCES OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE : AN EPIGRAPHIC AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY Alexander Panayotov A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2004 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13849 This item is protected by original copyright THE JEWS IN THE BALKAN PROVINCES OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE. AN EPIGRAPHIC AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY Alexander Panayotov PhD Candidate Submitted: 28lh January 2004 School of Divinity University of St Andrews Scotland ProQuest Number: 10170770 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10170770 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 I, ALEXANDER ANTONIEV PANAYOTOV, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 94,520 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. -

The Ancient People of Italy Before the Rise of Rome, Italy Was a Patchwork

The Ancient People of Italy Before the rise of Rome, Italy was a patchwork of different cultures. Eventually they were all subsumed into Roman culture, but the cultural uniformity of Roman Italy erased what had once been a vast array of different peoples, cultures, languages, and civilizations. All these cultures existed before the Roman conquest of the Italian Peninsula, and unfortunately we know little about any of them before they caught the attention of Greek and Roman historians. Aside from a few inscriptions, most of what we know about the native people of Italy comes from Greek and Roman sources. Still, this information, combined with archaeological and linguistic information, gives us some idea about the peoples that once populated the Italian Peninsula. Italy was not isolated from the outside world, and neighboring people had much impact on its population. There were several foreign invasions of Italy during the period leading up to the Roman conquest that had important effects on the people of Italy. First there was the invasion of Alexander I of Epirus in 334 BC, which was followed by that of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. Hannibal of Carthage invaded Italy during the Second Punic War (218–203 BC) with the express purpose of convincing Rome’s allies to abandon her. After the war, Rome rearranged its relations with many of the native people of Italy, much influenced by which peoples had remained loyal and which had supported their Carthaginian enemies. The sides different peoples took in these wars had major impacts on their destinies. In 91 BC, many of the peoples of Italy rebelled against Rome in the Social War.