Urban Design and Civic Spaces: Nature at the Parc Des Buttes-Chaumont in Paris Strohmayer, Ulf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Socialist Minority and the Paris Commune of 1871 a Unique Episode in the History of Class Struggles

THE SOCIALIST MINORITY AND THE PARIS COMMUNE OF 1871 A UNIQUE EPISODE IN THE HISTORY OF CLASS STRUGGLES by PETER LEE THOMSON NICKEL B.A.(Honours), The University of British Columbia, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2001 © Peter Lee Thomson Nickel, 2001 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Hi'sio*" y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date AkgaS-f 30. ZOO I DE-6 (2/88) Abstract The Paris Commune of 1871 lasted only seventy-two days. Yet, hundreds of historians continue to revisit this complex event. The initial association of the 1871 Commune with the first modern socialist government in the world has fuelled enduring ideological debates. However, most historians past and present have fallen into the trap of assessing the Paris Commune by foreign ideological constructs. During the Cold War, leftist and conservative historians alike overlooked important socialist measures discussed and implemented by this first- ever predominantly working-class government. -

Promenade Dans Le Parc Monceau

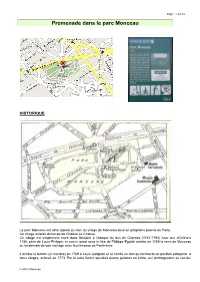

Page : 1 sur 16 Promenade dans le parc Monceau HISTORIQUE Le parc Monceau est ainsi appelé du nom du village de Monceau situé en périphérie proche de Paris. Ce village existait du temps de Charles Le Chauve. Ce village est simplement entré dans l’histoire à l’époque du duc de Chartres (1747-1793) futur duc d’Orléans 1785, père de Louis-Philippe, et connu aussi sous le titre de Philippe Egalité achète en 1769 la terre de Monceau au lendemain de son mariage avec la princesse de Penthièvre. Il achète le terrain (un hectare) en 1769 à Louis Colignon et lui confie en tant qu’architecte un pavillon octogonal, à deux étages, achevé en 1773. Par la suite furent ajoutées quatre galeries en étoile, qui prolongeaient au rez-de- Le Parc Monceau Page : 2 sur 16 chaussée quatre des pans, mais l'ensemble garda son unité. Colignon dessine aussi un jardin à la française c’est à dire arrangé de façon régulière et géométrique. Puis, entre 1773 et 1779, le prince décida d’en faire construire un autre plus vaste, dans le goût du jour, celui des jardins «anglo-chinois» qui se multipliaient à la fin du XVIIIe siècle dans la région parisienne notamment à Bagatelle, Ermenonville, au Désert de Retz, à Tivoli, et à Versailles. Le duc confie les plans à Louis Carrogis dit Carmontelle (1717-1806). Ce dernier ingénieur, topographe, écrivain, célèbre peintre et surtout portraitiste et organisateur de fêtes, décide d'aménager un jardin d'un genre nouveau, "réunissant en un seul Jardin tous les temps et tous les lieux ", un jardin pittoresque selon sa propre formule. -

Château De La Muette 2, Rue André Pascal Paris 75016 28 -30 June 2004

OECD SHORT-TERM ECONOMIC STATISTICS EXPERT GROUP MEETING (STESEG) Château de la Muette 2, rue André Pascal Paris 75016 28 -30 June 2004 INFORMATION General 1. The Short-term Economic Statistics Expert Group (STESEG) meeting is scheduled to be held at the OECD headquarters at 2, rue André Pascal, Paris 75016, from Monday 28 June to Wednesday 30 June 2004. 2. The meeting will commence at 9.30am on Monday 28 June 2004 and will be held in Room 2 for the first two days and Room 6 on the third day. Registration and identification badges 3. All delegates are requested to register with the OECD Security Section and to obtain ID badges at the Reception Centre, located at 2, rue André Pascal, on the first morning of the meeting. It is advisable to arrive there no later than 9.00am; queues often build up just prior to 9.30am because of the number of meetings which start at that time. Please note you should bring some form of photo identification with you. 4. For identification and security reasons, participants are requested to wear their security badges at all times while inside the OECD complex. Immigration requirements 5. Delegates travelling on European Union member country passports do not require visas to enter France. All other participants should check with the relevant French diplomatic or consular mission on visa requirements. If a visa is required, it is your responsibility to obtain it before travelling to France. If you need a formal invitation to support your visa application please contact the Statistics Directorate well before the meeting. -

Mapping Topographies in the Anglo and German Narratives of Joseph Conrad, Anna Seghers, James Joyce, and Uwe Johnson

MAPPING TOPOGRAPHIES IN THE ANGLO AND GERMAN NARRATIVES OF JOSEPH CONRAD, ANNA SEGHERS, JAMES JOYCE, AND UWE JOHNSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristy Rickards Boney, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Helen Fehervary, Advisor Professor John Davidson Professor Jessica Prinz Advisor Graduate Program in Professor Alexander Stephan Germanic Languages and Literatures Copyright by Kristy Rickards Boney 2006 ABSTRACT While the “space” of modernism is traditionally associated with the metropolis, this approach leaves unaddressed a significant body of work that stresses non-urban settings. Rather than simply assuming these spaces to be the opposite of the modern city, my project rejects the empty term space and instead examines topographies, literally meaning the writing of place. Less an examination of passive settings, the study of topography in modernism explores the action of creating spaces—either real or fictional which intersect with a variety of cultural, social, historical, and often political reverberations. The combination of charged elements coalesce and form a strong visual, corporeal, and sensory-filled topography that becomes integral to understanding not only the text and its importance beyond literary studies. My study pairs four modernists—two writing in German and two in English: Joseph Conrad and Anna Seghers and James Joyce and Uwe Johnson. All writers, having experienced displacement through exile, used topographies in their narratives to illustrate not only their understanding of history and humanity, but they also wrote narratives which concerned a larger global ii community. -

Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau | January 2017 01 PRESS RELEASE PARIS 2017 PARIS, the PLACE to BE

PRESS RELEASE PARIS 2017 2017 In 2017, Paris is full of appeal and surprises! Ever more welcoming, innovative, greener and live- lier, it is a vibrant and changing 21st century capital. An exceptional cultural calendar is without doubt the destination’s greatest a raction – blockbuster exhibitions, the opening of new presti- gious or original venues … Plus, museums and trendy bars, a galleries and design hotels, outs- tanding monuments and renowned restaurants all make Paris an ever more prominent capital, with multiple facets, always ready to surprise Parisians and visitors. PARIS CREATES A BUZZ. Some 300 events take place every day in Paris. Top events open to everyone include the Fête de la Musique (Music Day) , the Nuit des Musées (Museums at Night), Heritage Days, the Bastille Day fireworks display on July 14th, Paris Plages, Nuit Blanche and its a pe ormance, not forge ing the sparkling Christmas illuminations and New Year’s Eve celebrations on the Champs-Élysées. In 2017, Paris will be hosting some prominent exhibitions: Vermeer at the Musée du Louvre, Pissarro at the Musée Marmo an − Monet, and at the Musée du Luxembourg, Rodin at the Grand Palais, Picasso at the Musée du Quai Branly − Jacques Chirac, Balthus, Derain and Giacome i at the city’s Musée d’A Moderne, Cézanne at the Centre Pompidou, Rubens at the Musée du Luxembourg and © Musée du Louvre Gauguin at the Grand Palais … Modern and contemporary a enthusiasts will also be able to see the works of key international a ists such as David Hockney and Anselm Kiefer, and a end land- mark a shows Fiac and A Paris A Fair. -

Euro-Islam.Info -- Country Profiles

Paris Euro-Islam.info -- Country profiles -- Country profiles Paris Esebian Publié le Saturday 8 March 2008 Modifié le Friday 11 July 2008 Fichier PDF créé le Saturday 12 July 2008 Euro-Islam.info Page 1/7 Paris Demographics In French administrative organization, Paris is a French department. The Ile-de-France region comprises eight departments, including Paris. The other departments in the region are Hauts-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis, Val-de-Marne, Val-d'Oise Essonne, Yvelines and Seine-et-Marne (OSI 84). The Parisian suburbs make up the areas with the highest proportion of Muslims in France. According to a 1999 census, 1,611,008 immigrants live in the Ile-de-France region. Of this figure, 466,608 are from the Maghreb, 238,984 from Sub-Saharan Africa, and 50,125 from Turkey. These three groups of immigrant populations comprise nearly 50% of the immigration population in the Ile-de-France region. Accurate data on the large numbers of immigrant descendants and children are unavailable (OSI 84). The North-African population lives predominantly in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, Yvelines, and Val-de-Marne. Immigrants with Sub-Saharan origins mostly reside in the city center - in particular, the 18th, 19th, and 20th arrondissement and in three suburban cities: Bobigny in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, Vitry-sur-Seine in the Val de Marne department, and Cergy in the Val-d'Oise department (OSI 84-85). The arrival of the first waves of Muslim immigrants coincided with alterations of Parisian living conditions. While many arrived to shanty-towns on the city's limits, later housing often lacked running water, and sanitary facilities. -

UNE NUIT BLANCHE MÉTROPOLITAINE #Nuitblanche Nuitblanche.Paris

UNE NUIT BLANCHE MÉTROPOLITAINE #nuitblanche nuitblanche.paris SAINTDENIS GENNEVILLIERS AUBERVILLIERS SAMEDI 5 OCTOBRE 2019 5 OCTOBRE SAMEDI studio Muchir Desclouds Muchir studio SIGNES DES STATION NORD graphisme : PÉRIPHÉRIQUE LE VÉLODROME STATION OUEST PANTIN 1 COURBEVOIE NOISYLESEC LA DÉFENSE 1 PARC DE LA VILLETTE BOIS DE BOULOGNE ASSOCIÉS MÉDIAS PARTENAIRES Kid, Citizen Minutes, 20 Mapstr, Paris Mômes COPRODUCTION PARTENAIRES ET MÉDIATION Accès Culture, Âge d’or du conte,de France – L’art Art Culture et Foi, Médicis,Art Paris, Ateliers Kids Centre Pompidou, BR-Units, Recherche Centre Théâtre Handicap - CRTH, Centre Wallonie-Bruxelles, universitaire internationale Cité de Paris, Cneai - Centre National, Édition Art Image, Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, Galleria Continua, Le Fresnoy - Studio national des arts contemporains, Les Grands Voisins, Les Papillons Blancs de Paris, Les Souffleursd’Images, Mondial Ville, en Mobile Opéra Comique, Tatouage, du Wowow Vélib’, RUEILMALMAISON PARIS 19 LES LILAS 1 STATION CENTRE LA GRANDE TRAVERSÉE 2 3 avec En collaboration 2 PARTENAIRES PRINCIPAUX Adidas, Paris Aéroport, LVMH, SNCF Gares & Connexions, France Télévisions, Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé ASSOCIÉS PARTENAIRES Chronopost, Crédit ADAGP, Paris, Délégation de Municipal générale du Québec à Paris, Evesa, Desigual, Ricard, d’entreprise Fondation Elysées dotation de Fonds Monceau, Le BHV Marais, Le Perchoir, Saint-Gobain, Société d’Exploitation Eiffel, de la Tour Société Lyonnaise, Foncière Société du Grand Paris, Westfield – Forum des Halles MÉDIAS PARTENAIRES L’Équipe, Libération, Le Bonbon, RATP 1 MONTREUIL 16 11 LA PARADE 4 SE RENSEIGNER SE REPERER / SE DÉPLACER 6 VINCENNES SUR LE WEB LA CARTE @NUITBLANCHE 7 Retrouvez le programme SUR MAPSTR de Nuit Blanche sur nuitblanche.paris Pour retrouver l’ensemble des adresses 5 PARC FLORAL → Accessible depuis votre ordinateur, de la programmation ainsi que tablette et smartphone. -

Trade Climate Events Final Email

With thanks to: SustainUS, Federation of Young Europe- an Greens (FYEG) , Corporate Europe Obser- vatory (CEO), European Parliament, Collective StopTAFTA, Attac France, Solidaire, Center for Justice and & Accountability, J.E.D.I. for climate, Confedera- tion Paysanne, IEN, Ruckus, Frack-free Europe, Climate Games, Association Internationale de Techniciens, Experts et Chercheurs (Aitec), Global Trade Justice Now, Seattle 2 Brussels network, French Stop TAFTA platform, Observatoire des multina- tionales, Attac, Global Campaign to Dismantle Corporate Power and Stop Impunity, Sierra & Club, Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy and Global Forest Coalition, Transport & Environment (T&E), Coalition Climat, 350.org, CJA, Confédération Paysanne, Réseau sortir du nucléair, Reclaim the Power, WWF, CCFD, GreenPeace, Friends of the Earth, climate Alternatiba, Réseau québécois sur l'intégration conti- nentale (RQIC), Transnational Institute (TNI) events at Paris COP 21 Scan here for more information Date + time Name of event Type of event Location November Friday 27th Trade is a Climate Issue - Strategy for COP21 Strategy session & action Conference of the Youth (COY) - Parc des Expositions of Villepinte 14:30-16:30 and Beyond planning Saturday 28th TTIP = Climate Chaos Conference Conference Conference of the Youth (COY) - Parc des Expositions of Villepinte 13:30-16:00 Sunday 29th Global Climate March Human chains To be confirmed December Trade Friday 4th Action: Fausses Solution COP21 Actions Grand Palais (centre of Paris) Saturday 5th - "The -

Découvrez Les Lieux De Tournage Discover Where the fi Lm Was Shot PARCOURS CINÉMA DANS PARIS N°1 PARIS FILM TRAILS

PARCOURS CINÉMA DANS PARIS N°1 PARIS FILM TRAILS Découvrez les lieux de tournage Discover where the fi lm was shot PARCOURS CINÉMA DANS PARIS N°1 PARIS FILM TRAILS Les Parcours Cinéma vous invitent à découvrir Paris, ses quartiers célèbres et insolites à tra- vers des fi lms emblématiques réalisés dans la Capitale. Chaque année, Paris accueille plus de 650 tournages dans 4 000 lieux de décors naturels. Ces Parcours Cinéma sont des guides pour tous les amoureux de Paris et du Cinéma. Follow the Paris Film Trails and explore famous or little-known parts of the city that have featured in classic movies. Over 650 fi lm shoots take place in Paris each year, and some 4,000 different outside locations have been used. The Film Trails are pocket guides for lovers of Paris and the cinema. Mission Cinéma - Mairie de Paris • www.cinema.paris.fr Raconter en cinq minutes l’histoire d’une Tell the story of an amorous encounter rencontre amoureuse dans un quartier de somewhere in Paris – in just fi ve minutes. Paris, tel est le défi qu’ont accepté de relever, avec This was the challenge that twenty fi lm-makers PARIS JE T’AIME, vingt et un réalisateurs venus du from around the world agreed to take up for PARIS monde entier. Ils réinventent notre regard sur Paris JE T’AIME. The result is a sensitive and moving fi lm et nous livrent un fi lm sensible et émouvant... that makes us look at Paris in a new light... Montmartre Bastille Pigalle Écrit et réalisé par Bruno Podalydès Écrit et réalisé par Isabel Coixet Écrit et réalisé par Richard LaGravenese Florence Muller -

World Geomorphological Landscapes

World Geomorphological Landscapes Series Editor: Piotr Migoń For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10852 Monique Fort • Marie-Françoise André Editors Landscapes and Landforms o f F r a n c e Editors Monique Fort Marie-Françoise André Geography Department, UFR GHSS Laboratory of Physical CNRS UMR 8586 PRODIG and Environmental Geography (GEOLAB) University Paris Diderot-Sorbonne-Paris-Cité CNRS – Blaise Pascal University Paris , France Clermont-Ferrand , France Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the fi gures and tables which have been reproduced from other sources. Anyone who has not been properly credited is requested to contact the publishers, so that due acknowledgment may be made in subsequent editions. ISSN 2213-2090 ISSN 2213-2104 (electronic) ISBN 978-94-007-7021-8 ISBN 978-94-007-7022-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-7022-5 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013944814 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

Paris Dansant? Improvising Across Urban, Racial and International Geographies in the Early Cancan

Paris Dansant? Improvising across urban, racial and international geographies in the early cancan Clare Parfitt-Brown University of Chichester, UK Abstract This paper addresses the cancan - not the familiar choreographed performance, but the improvised social dance that emerged among working-class dancers in 1820s Paris. Sources from the period reveal working men and women traversing not only a complex Parisian landscape of popular dance spectatorship and performance, but also taking advantage of Paris’s status as an international metropole to consume non-French movement. After observing performances of ‘national’ dance forms (such as the Spanish cachucha and the Haitian chica) at the popular theatres of the Boulevard du Temple in north-east Paris, working-class dancers incorporated these movements into their dancing at the suburban guinguettes (dance venues) outside the city walls. These variations became known as the cancan or chahut. In the early 1830s, the cancan became popular at the mixed-class masked carnival balls that took place in central Parisian theatres, such as the Paris Opéra. By the 1840s, the dance had come to embody the pleasures and dangers of a Parisian nightlife based on class and gender confusion, subversion and deception, documented in books such as Physiologie des bals de Paris (1841) and Paris au bal (1848). As the cancan was increasingly incorporated into the mythology of July Monarchy Paris, the class and gender subversions of the dance obscured the international and racial ambiguities that haunted its inception. This paper therefore focuses on the tensions between the cancan’s status as ‘Parisian’, and as an embodiment of a popular culture based on fascination with France’s European and colonial others in the 1820s. -

TONINO BENACQUISTA Is One of French Literature’S Most Versatile Talents

VÉRONIQUE M. LE NORMAND writes children’s books, novels, short stories and poetry. Born in Brittany and a former journalist with Marie-Claire magazine, she lives in Paris with her husband Daniel Pennac. For Le Roman de Noémie (2006) she was nominated for the Prix Goncourt des lycéens allemands. Her album J’aime (2006), illustrated by Natali Fortier, was selected for the Bologna Children’s Book Fair and has been translated into numerous languages around the world. Her web-site is at www.minne.me and she is on Facebook at www.facebook.com/pages/Véronique-M-Le-Normand- FeaturedParticipants Minne/298843867643. DANIEL PENNAC has redesigned the literary geography of Paris. In the northeastern part of the city TONINO BENACQUISTA is one of French literature’s most versatile talents. His work in cinema as is a section called Belleville, a sprawling, multi-ethnic neighborhood which Daniel Pennac claims to be a script-writer led to his winning Césars (the European equivalents of Oscars) for the screenplays of the only truly integrated part of the nation’s capital. Until recently Belleville was such an insular space Sur mes lèvres (Read My Lips) (2001) and De battre mon coeur s’est arrêté (The Beat That My Heart Skipped) in the city that it really did not even seem like Paris. But then the Malaussène family arrived via Daniel (2006). He began his career as a writer with a series of well-received mystery novels that he researched Pennac’s imagination. The family or rather tribe has numerous offspring, several adopted siblings and a in part while working on the French railroads.