Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resonare 1, No. 1

A Study in Violin Pedagogy: Teaching Techniques from Selected Works by Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Bartók, and Delerue Layne Vanderbeek This article is an outline and analysis of a few specific methods of composition used by the composers Sergei Rachmaninoff, Sergei Prokofiev, Béla Bartók, and Georges Delerue for the purpose of reproducing the styles and techniques for an intermediate level violinist. This will be accomplished by gathering information concerning each composer and their style and then reproducing that style in an original composition at the intermediate level. Each composer will be dealt with in a section divided into several parts: relevant biographical and historical information, stylistic analysis, and methods employed to incorporate these stylistic characteristics into the intermediate level composition. The biographical and historical information will consist of pertinent historic, social, and political events that influenced compositional style and growth of each composer. Stylistic analysis will be based upon general historical information and analysis of the specific composition in consideration. Scalar resources, chord and harmony use, texture and rhythm will be discussed and illustrated. The incorporation of these stylistic elements into an intermediate level composition will be a direct conclusion to the previous section. The information gained in the stylistic analysis will be utilized in original intermediate compositions, and it will be illustrated how this is accomplished and how these twentieth-century techniques are being employed and incorporated. Within the section titled “Methods of Stylistic Incorporation,” portions of the intermediate compositions will be used to demonstrate aspects of the composers' styles that were included. Each complete intermediate composition will be placed at the end of each section to demonstrate the results of the analysis. -

Xin Bấm Vào Đây Để Mở Hoặc Tải Về

HOÀI NAM (Biên Soạn) NHỮNG CA KHÚC NHẠC NGOẠI QUỐC LỜI VIỆT (Tập Bốn) NHẠC ĐÔNG PHƯƠNG – NHẠC PHIM Trình Bày: T.Vấn Tranh Bìa: Mai Tâm Ấn Bản Điện Tử do T.Vấn & Bạn Hữu Thực Hiện ©Tủ Sách T.Vấn & Bạn Hữu 2021 ©Hoài Nam 2021 ■Tất cả những hình ảnh sử dụng trong bài đều chỉ nhằm mục đích minh họa và chúng hoàn toàn thuộc về quyền sở hữu theo luật quốc tế hiện hành của các tác giả hợp pháp của những hình ảnh này.■ MỤC LỤC TỰA THAY LỜI CHÀO TẠM BIỆT Phần I – Nhạc Đông Phương 01- Ruju (Người Tình Mùa Đông, Thuyền Tình Trên Sóng) 006 02- Koibito Yo (Hận Tình Trong Mưa, Tình Là Giấc Mơ) 022 03- Ribaibaru (Trời Còn Mưa Mãi, Tiễn Em Trong Mưa) 039 04- Ánh trăng nói hộ lòng tôi (Ánh trăng lẻ loi) 053 05- Hà Nhật Quân Tái Lai (Bao Giờ Chàng Trở Lại,. .) 067 06- Tsugunai (Tình chỉ là giấc mơ, Ước hẹn) 083 Phần II – Nhạc Phim 07- Dẫn Nhập 103 08- Eternally (Terry’s Theme, Limelight) 119 09- Que Será Será (Whatever will be, will be) 149 10- Ta Pedia tou Pirea /Never On Sunday) 166 11- The Green Leaves of Summer, Tiomkin & Webster 182 12- Moon River, Henri Mancini & Johnny Mercer 199 13- The Shadow of Your Smile, Johnny Mandel & . 217 14- Somewhere, My Love (Hỡi người tình Lara/Người yêu tôi đâu 233 15- A Time For Us (Tình sử Romeo & Juliet), 254 16- Where Do I Begin? Love Story, (Francis Lai & Carl Sigman) 271 17- The Summer Knows (Hè 42, Mùa Hè Năm Ấy) 293 18- Speak Softly, Love (Thú Đau Thương) 313 19- I Don’t Know How To Love Him (Chuyện Tình Xưa) 329 20- Thiên Ngôn Vạn Ngữ (Mùa Thu Lá Bay) 350 21- Memory (Kỷ Niệm) 369 22- The Phantom of the Opera (Bóng ma trong hí viện) 384 23- Unchained Melody (Tình Khúc Rã Rời,. -

A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Lip-Syncing in American and Indian Film Lucie Alaimo

Unsung Heroes? A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Lip-Syncing in American and Indian Film Lucie Alaimo Who are these unsung heroes? They are the voice-dubbers in Hollywood film. Throughout the history of Hollywood, actors and actresses have resorted to voice-dubbing in films in which they have had singing numbers. However, in American music performance practices, especially in the popular music and film industries, lip-syncing is often criticized, leading to debate over the technique. In comparison, Bollywood films also feature voice- dubbing, and although there is hostility towards this technique in Hollywood, it is perfectly acceptable in the Indian film industry. The majority of Bollywood films feature singing, and in all, it is the role of the voice-dubbers, also known as playback singers, to provide voices for the film stars. In addition, many of Bollywood’s playback singers have become as popular as, if not more than, the actors and actresses for whom they sing. Much of the reason for this stark difference in acceptance of voice-dubbers is found in the different ideologies of authenticity surrounding the use of lip-syncing. In North America, listeners expect perfection in the performances, yet are disappointed when discovering that there are elements of inauthenticity in them. Yet in India, both film producers and audiences have accepted the need for the talents of multiple people to become involved in the film production. In this paper, I will first discuss ideologies surrounding musical authenticity, then compare how these discourses have shaped and influenced the acceptance or rejection of voice-dubbers in Hollywood and Bollywood films. -

Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice

Lipsynching: Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice Merrie Snell Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Cultures April 2015 Abstract This thesis is an exploration and problematization of the practice of lipsynching to pre- recorded song in both professional and vernacular contexts, covering over a century of diverse artistic practices from early sound cinema through to the current popularity of vernacular internet lipsynching videos. This thesis examines the different ways in which the practice provides a locus for discussion about musical authenticity, challenging as well as re-confirming attitudes towards how technologically-mediated audio-visual practices represent musical performance as authentic or otherwise. It also investigates the phenomenon in relation to the changes in our relationship to musical performance as a result of the ubiquity of recorded music in our social and private environments, and the uses to which we put music in our everyday lives. This involves examining the meanings that emerge when a singing voice is set free from the necessity of inhabiting an originating body, and the ways in which under certain conditions, as consumers of recorded song, we draw on our own embodiment to imagine “the disembodied”. The main goal of the thesis is to show, through the study of lipsynching, an understanding of how we listen to, respond to, and use recorded music, not only as a commodity to be consumed but as a culturally-sophisticated and complex means of identification, a site of projection, introjection, and habitation, -

Playback Singers of Bollywood and Hollywood

ILLUSION AND REALITY: PLAYBACK SINGERS OF BOLLYWOOD AND HOLLYWOOD By MYRNA JUNE LAYTON Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject MUSICOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA. SUPERVISOR: PROF. M. DUBY JANUARY 2013 Student number: 4202027-1 I declare that ILLUSION AND REALITY: PLAYBACK SINGERS OF BOLLYWOOD AND HOLLYWOOD is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. SIGNATURE DATE (MRS M LAYTON) Preface I would like to thank the two supervisors who worked with me at UNISA, Marie Jorritsma who got me started on my reading and writing, and Marc Duby, who saw me through to the end. Marni Nixon was most helpful to me, willing to talk with me and discuss her experiences recording songs for Hollywood studios. It was much more difficult to locate people who work in the Bollywood film industry, but two people were helpful and willing to talk to me; Craig Pruess and Deepa Nair have been very gracious about corresponding with me via email. Lastly, putting the whole document together, which seemed an overwhelming chore, was made much easier because of the expert formatting and editing of my daughter Nancy Heiss, sometimes assisted by her husband Andrew Heiss. Joe Bonyata, a good friend who also happens to be an editor and publisher, did a final read-through to look for small details I might have missed, and of course, he found plenty. For this I am grateful. -

The Trademark Function of Authorship

THE TRADEMARK FUNCTION OF AUTHORSHIP ∗ GREG LASTOWKA INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1172 I. AUTHORIAL ATTRIBUTION AND SOCIETY.......................................... 1175 A. Attribution as Incentive ............................................................. 1176 B. Attribution as Consumer Protection.......................................... 1179 C. Attribution as Value................................................................... 1180 II. LEGAL REGULATION OF AUTHORIAL ATTRIBUTION ......................... 1185 A. Misattribution and Trademark Law .......................................... 1186 1. Trademark’s Purpose........................................................... 1186 2. Authorship as Trademark .................................................... 1193 3. Authorship vs. Trademark................................................... 1194 B. The Dastar Decision .................................................................. 1200 C. Misattribution and Copyright.................................................... 1210 1. The Meaning of VARA....................................................... 1211 2. Copyright as Collateral Attribution Protection.................... 1214 3. The Attribution/Copyright Mismatch.................................. 1217 D. Misrepresentation and Other Legal Mechanisms...................... 1218 III. AUTHORSHIP, CONSUMERS, AND COLLABORATION .......................... 1221 A. Ghostwriting............................................................................. -

BULLETIN DU CICLAHO N° 5 Du Classicisme À L'hyperclassicisme

Centre de Recherches de l’U.F.R. d'Études Anglo-Américaines BULLETIN DU CICLAHO N° 5 MÉMOIRE(S) D’HOLLYWOOD : du classicisme à l’hyperclassicisme Sous la direction de Dominique Sipière et Serge Chauvin UNIVERSITÉ PARIS X OUEST NANTERRE LA DEFENSE 2009 © Centre de Recherches d'Études Anglo-Américaines, 2009 N° ISBN : 2-907335- ??- ? Pour se procurer ces publications : Diffusion Bât. A, bureau 321 Télécopie 01.40.97.72.88 Illustration de couverture : Greta Garbo dans Ninotchka et Cyd Charisse dans Silk Stockings Bulletin du Ciclaho, n° 5 Mémoire(s) d’Hollywood : du classicisme à l’hyperclassicisme Sommaire Dominique Sipière et Serge Chauvin ( SUP) Introduction ........................................................................................... 7 Jean Marie Lecomte, Nancy L’imagination verbale dans les premiers parlants (1937-1936) .......... 9 Katalin Por, Metz La réinvention de l’Europe dans les comédies hollywoodiennes des années 30......................................................................................... 29 Alain Masson, Positif Le Baiser hollywoodien ......................................................................... 47 Trudy Bolter, Bordeaux Renoir américain ? Des liens de parenté pour L’Homme du sud ....... 61 Anne Martina, Paris IV Hollywood Follies : l’influence de la revue sur le musical des années 40 ........................... 73 Dominique Sipière, Paris X Le violent corps à corps de la démocratie : films de boxe des années 40 .................................................................. 87 Christian -

Recorded Jazz in the Early 21St Century

Recorded Jazz in the Early 21st Century: A Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull. Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 The Consumer Guide: People....................................................................................................................7 The Consumer Guide: Groups................................................................................................................119 Reissues and Vault Music.......................................................................................................................139 Introduction: 1 Introduction This book exists because Robert Christgau asked me to write a Jazz Consumer Guide column for the Village Voice. As Music Editor for the Voice, he had come up with the Consumer Guide format back in 1969. His original format was twenty records, each accorded a single-paragraph review ending with a letter grade. His domain was rock and roll, but his taste and interests ranged widely, so his CGs regularly featured country, blues, folk, reggae, jazz, and later world (especially African), hip-hop, and electronica. Aside from two years off working for Newsday (when his Consumer Guide was published monthly in Creem), the Voice published his columns more-or-less monthly up to 2006, when new owners purged most of the Senior Editors. Since then he's continued writing in the format for a series of Webzines -- MSN Music, Medium, -

The Chrysanthemum Symbol of Strength and Resilience National Palace Museum Cora Wang Away from the Bustle of City Life

WEEK 43, 2020 TRADITIONAL CULTURE The Chrysanthemum Symbol of Strength and Resilience NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM CORA WANG away from the bustle of city life. As a result, the s the chill of autumn chrysanthemum became sets in, trees be- a symbol of seclusion and gin to lose their a life free of materialism. vibrancy, and Aplants begin to wilt. How- A Righteous Heart ever, one particular flower This characterization of prevails—the chrysanthe- the chrysanthemum can mum. While its surround- further be seen in litera- ings fade away, defeated by ture, such as in the story the frigid winds, this resil- “Yuchu Xinzhi.” Written ient flower starts to bloom. in the Qing Dynasty, it Since ancient times, the tells the tale of a scholar chrysanthemum has been named Gao Chan. He was admired by Chinese schol- viewed as peculiar by his ars and literati, inspiring fellow intellectuals, as he countless poems, stories, had no desire for fame or and artworks. Besides wealth, and was often at praising it for its beauty, odds with the Confucian they celebrated it as a sym- scholars prevalent at the bol of vitality and tenacity. time. Gao Chan kept a low profile, but he was known Humble Origins by those close to him for One of the earliest in- his kindness and righ- stances of the chrysan- teousness. He was always themum being refer- seeking self-improvement enced in poetry is in Qu and frequently carried out Yuan’s famous poem “Li good deeds in secret. Sao,” composed during Gao Chan felt disillu- the Warring States period. -

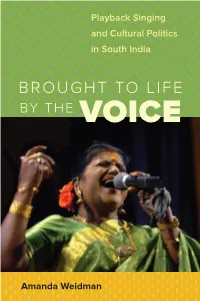

Brought to Life by the Voice Explores the Distinctive Aesthetics and in South India

ASIAN STUDIES | ANTHROPOLOGY | ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WEIDMAN Playback Singing To produce the song sequences that are central to Indian popular cinema, sing- ers’ voices are first recorded in the studio and then played back on the set to and Cultural Politics be lip-synced and danced to by actors and actresses as the visuals are filmed. Since the 1950s, playback singers have become revered celebrities in their | own right. Brought to Life by the Voice explores the distinctive aesthetics and in South India affective power generated by this division of labor between onscreen body and VOICE THE BY LIFE TO BROUGHT offscreen voice in South Indian Tamil cinema. In Amanda Weidman’s historical and ethnographic account, playback is not just a cinematic technique, but a powerful and ubiquitous element of aural public culture that has shaped the complex dynamics of postcolonial gendered subjectivity, politicized ethnolin- guistic identity, and neoliberal transformation in South India. BROUGHT TO LIFE “This book is a major contribution to South Asian Studies, sound and music studies, anthropology, and film and media studies, offering original research and BY THE new theoretical insights to each of these disciplines. There is no other scholarly work that approaches voice and technology in a way that is both as theoretically VOICE wide-ranging and as locally specific.” NEEPA MAJUMDAR, author of Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s–1950s “Brought to Life by the Voice provides a detailed and highly convincing explo- ration of the varying links between the singing voice and the body in the Tamil film industry since the mid-twentieth century. -

Songs and Broadway Musicals

Week #2 June 17-23, 2019 • Due by 5:00 p.m. on Sunday, June 23 Name:___________________________________ Phone Number:_____________________________ Due by 5:00 p.m. on Sunday, June 23. Please return completed quizzes to the Reference/Reader Services Desk. Must be received before 5:00 p.m. on the appropriate Sunday; drawings will be held the following Monday & winners notified within two days. Songs and Broadway Musicals 1. From what classical Broadway musical starring Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer are the following songs featured: “Sixteen Going on Seventeen,” “Favorite Things,” and “Do-Re-Me”?____________________________________________________________________ 2. What legendary Hollywood actress sings the number “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” from the 1953 movie musical Gentlemen Prefer Blondes? ______________________________________________________________________________ 3. What song performed by Dolly Levi (as originated played by Carol Channing) in the 1964 Broadway musical Hello, Dolly! concludes Act I before intermission? ______________________________________________________________________________ 4. What were the names of the successful American musical theater writing team who created Oklahoma!, Carousel, South Pacific, and The King and I? ______________________________________________________________ 5. What is the name of 1952 musical movie (also the same name of its signature song) starring Gene Kelly, Donald O’Connor, and Debbie Reynolds? ________________________________ 6. How many trombones are in the title song of the classic musical The Music Man? ____________________________________________________ 7. What American soprano dubbed some of Audrey Hepburn’s title songs in My Fair Lady? This individual was a ghost singer for featured actors in movie musicals including in The King and I and West Side Story. ______________________________________________________________ 8. The legendary Julie Andrews is considered to be a singer in what vocal range? ____________________________________________________________ 9. -

The Afterlife of Maria Callas's Voice

Music and Culture The Afterlife of Maria Callas’s Voice Michal Grover-Friedlander I. Bygone Voices It is indeed impossible to imagine our own death; and whenever we attempt to do so we can perceive that we are in fact still present as spectators . at bottom no one believes in his own death, or, to put the same thing in another way, that in the unconscious every one of us is convinced of his own immortality. —Sigmund Freud, “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death” [Maria Callas’s] record company has succeeded in making people think she is still alive. It’s a little bit like conversations with the other world. —Manuela Hoelterhoff, Cinderella & Company Am I hearing voices within the voice? But isn’t it the truth of the voice to be hal- lucinated? Isn’t the entire space of the voice an infinite one? —Roland Barthes, “The Grain of the Voice” Callas Forever, Franco Zeffirelli’s 2002 film, abounds with references to comebacks, second chances, reclaiming one’s life, mourning over one’s lost voice, and questions of immortality.1 It is a surprising film. Rather than reconstructing Maria Callas’s life twenty-five years after her death, it depicts what could have happened in the last few months of her life. The fictionalized account is not intended to correct Callas’s biography in any simple sense: in fact, it tells of failures. To Callas Forever’s invented plot–– a Callas comeback on film––Callas herself ultimately objects. Callas Forever is not set at the diva’s prime, but in 1977, when she no longer possessed a singing voice.2 When, in 1970, Pier Paolo Pasolini cast Callas in Medea, the diva’s one and only (real) appearance on film, Callas famously did not sing.3 Catherine Clément argues that Pasolini captured doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdi005 88:35–62 Advance Access publication January 11, 2006 © The Author 2006.