Popular Song Recordings and the Disembodied Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYSTA January-February 2013.Pmd

1 VOICEPrints JOURNAL OF THE NEW YORK SINGING TEACHERS’ ASSOCIATION January-- February 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS: FEATURED EVENT and COURSE............................................................................................................. .........Page 1 Message from President David Sabella-Mills....................................................................................................Page 2 Message from Editor Matthew Hoch.............................................................................................................. Page 2 NYSTA 2013 Calendar of Events................................................................................................................. .Page 3 FEATURE ARTICLE: Getting to Know Marni Nixon by NYSTA Member Sarah Adams Hoover, DMA..........Pages 4--5 FEATURE ARTICLE: VOCEVISTA: Using Visual Real-Time Feedback by NYSTA Member Deborah Popham, DMA............................................................................Pages 6--7 NYSTA New Member..................................................................................................................................... .Page 8 Dean Williamson Master Class: October 25, 2012............................................................................................Page 8 NYSTA Board of Directors ...............................................................................................................................Page 8 OREN LATHROP BROWN PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM FEATURED EVENT: FEATURED COURSE: WINTER 2013 ONLINE -

Eckart Voigts-Virchow: Männerphantasien

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Werner Barg Eckart Voigts-Virchow: Männerphantasien. Introspektion und gebrochene Wirklichkeitsillusion im Drama von Dennis Potter 1996 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep1996.4.4187 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Barg, Werner: Eckart Voigts-Virchow: Männerphantasien. Introspektion und gebrochene Wirklichkeitsillusion im Drama von Dennis Potter. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 13 (1996), Nr. 4, S. 469– 470. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep1996.4.4187. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

Reallusion Premieres Iclone 1.52 - New Technology for Independent Machinima

For Immediate Release Reallusion Premieres iClone 1.52 - New Technology for Independent Machinima New York City - November 1st, 2006 – Reallusion, official Academy of Machinima Arts and Sciences’ Machinima Festival partner hits the red carpet with the iClone powered Best Visual Design nominee, “Reich and Roll”, an iClone film festival feature created by Scintilla Films, Italy. iClone™ is the 3D real-time filmmaking engine featuring complete tools for character animation, scene building, and movie directing. Leap from brainstorm to screen with advanced animation and visual effects for 3D characters, animated short-films, Machinima, or simulated training. The technology of storytelling evolves with iClone. Real-time visual effects, character interaction, and cameras all animate in with vivid quality providing storytellers instant visualization into their world. Stefano Di Carli, Director of ‘Reich and Roll’ says, “Each day I find new tricks in iClone. It's really an incredible new way of filmmaking. So Reallusion is not just hypin' a product. What you promise on the site is true. You can do movies!” Machinima is a rising genre in independent filmmaking providing storytellers with technology to bring their films to screen excluding high production costs or additional studio staff. iClone launches independent filmmakers and studios alike into a production power pack of animation tools designed to simplify character creation, facial animation, and scene production for 3D films. “iClone Independent filmmakers can commercially produce Machinima guaranteeing that the movies you make are the movies you own and may distribute or sell,” said John Martin II, Director of Product Marketing of Reallusion. “iClone’s freedom for filmmakers who desire to own and market their films supports the new real-time independent filmmaking spirit and the rise of directors who seek new technologies for the future of film.” iClone Studio 1.52 sets the stage delivering accessible directing tools to develop and debut films with speed. -

About Endgame

IN ASSOCIATION WITH BLINDER FILMS presents in coproduction with UMEDIA in association with FÍS ÉIREANN / SCREEN IRELAND, INEVITABLE PICTURES and EPIC PICTURES GROUP THE HAUNTINGS BEGIN IN THEATERS MARCH, 2020 Written and Directed by MIKE AHERN & ENDA LOUGHMAN Starring Maeve Higgins, Barry Ward, Risteárd Cooper, Jamie Beamish, Terri Chandler With Will Forte And Claudia O’Doherty 93 min. – Ireland / Belgium – MPAA Rating: R WEBSITE: www.CrankedUpFilms.com/ExtraOrdinary / http://rosesdrivingschool.com/ SOCIAL MEDIA: Facebook - Twitter - Instagram HASHTAG: #ExtraOrdinary #ChristianWinterComeback #CosmicWoman #EverydayHauntings STILLS/NOTES: Link TRAILER: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1TvL5ZL6Sc For additional information please contact: New York: Leigh Wolfson: [email protected]: 212.373.6149 Nina Baron: [email protected] – 212.272.6150 Los Angeles: Margaret Gordon: [email protected] – 310.854.4726 Emily Maroon – [email protected] – 310.854.3289 Field: Sara Blue - [email protected] - 303-955-8854 1 LOGLINE Rose, a mostly sweet & mostly lonely Irish small-town driving instructor, must use her supernatural talents to save the daughter of Martin (also mostly sweet & lonely) from a washed-up rock star who is using her in a Satanic pact to reignite his fame. SHORT SYNOPSIS Rose, a sweet, lonely driving instructor in rural Ireland, is gifted with supernatural abilities. Rose has a love/hate relationship with her ‘talents’ & tries to ignore the constant spirit related requests from locals - to exorcise possessed rubbish bins or haunted gravel. But! Christian Winter, a washed up, one-hit-wonder rock star, has made a pact with the devil for a return to greatness! He puts a spell on a local teenager- making her levitate. -

Facial Animation: Overview and Some Recent Papers

Facial animation: overview and some recent papers Benjamin Schroeder January 25, 2008 Outline Iʼll start with an overview of facial animation and its history; along the way Iʼll discuss some common approaches. After that Iʼll talk about some notable recent papers and finally offer a few thoughts about the future. 1 Defining the problem 2 Historical highlights 3 Some recent papers 4 Thoughts on the future Defining the problem Weʼll take facial animation to be the process of turning a characterʼs speech and emotional state into facial poses and motion. (This might extend to motion of the whole head.) Included here is the problem of modeling the form and articulation of an expressive head. There are some related topics that we wonʼt consider today. Autonomous characters require behavioral models to determine what they might feel or say. Hand and body gestures are often used alongside facial animation. Faithful animation of hair and rendering of skin can greatly enhance the animation of a face. Defining the problem This is a tightly defined problem, but solving it is difficult. We are intimately aware of how human faces should look, and sensitive to subtleties in the form and motion. Lip and mouth shapes donʼt correspond to individual sounds, but are context-dependent. These are further affected by the emotions of the speaker and by the language being spoken. Many different parts of the face and head work together to convey meaning. Facial anatomy is both structurally and physically complex: there are many layers of different kinds of material (skin, fat, muscle, bones). Defining the problem Here are some sub-questions to consider. -

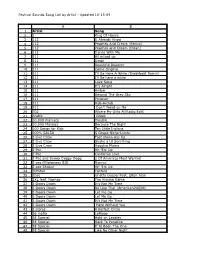

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Resonare 1, No. 1

A Study in Violin Pedagogy: Teaching Techniques from Selected Works by Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Bartók, and Delerue Layne Vanderbeek This article is an outline and analysis of a few specific methods of composition used by the composers Sergei Rachmaninoff, Sergei Prokofiev, Béla Bartók, and Georges Delerue for the purpose of reproducing the styles and techniques for an intermediate level violinist. This will be accomplished by gathering information concerning each composer and their style and then reproducing that style in an original composition at the intermediate level. Each composer will be dealt with in a section divided into several parts: relevant biographical and historical information, stylistic analysis, and methods employed to incorporate these stylistic characteristics into the intermediate level composition. The biographical and historical information will consist of pertinent historic, social, and political events that influenced compositional style and growth of each composer. Stylistic analysis will be based upon general historical information and analysis of the specific composition in consideration. Scalar resources, chord and harmony use, texture and rhythm will be discussed and illustrated. The incorporation of these stylistic elements into an intermediate level composition will be a direct conclusion to the previous section. The information gained in the stylistic analysis will be utilized in original intermediate compositions, and it will be illustrated how this is accomplished and how these twentieth-century techniques are being employed and incorporated. Within the section titled “Methods of Stylistic Incorporation,” portions of the intermediate compositions will be used to demonstrate aspects of the composers' styles that were included. Each complete intermediate composition will be placed at the end of each section to demonstrate the results of the analysis. -

Xin Bấm Vào Đây Để Mở Hoặc Tải Về

HOÀI NAM (Biên Soạn) NHỮNG CA KHÚC NHẠC NGOẠI QUỐC LỜI VIỆT (Tập Bốn) NHẠC ĐÔNG PHƯƠNG – NHẠC PHIM Trình Bày: T.Vấn Tranh Bìa: Mai Tâm Ấn Bản Điện Tử do T.Vấn & Bạn Hữu Thực Hiện ©Tủ Sách T.Vấn & Bạn Hữu 2021 ©Hoài Nam 2021 ■Tất cả những hình ảnh sử dụng trong bài đều chỉ nhằm mục đích minh họa và chúng hoàn toàn thuộc về quyền sở hữu theo luật quốc tế hiện hành của các tác giả hợp pháp của những hình ảnh này.■ MỤC LỤC TỰA THAY LỜI CHÀO TẠM BIỆT Phần I – Nhạc Đông Phương 01- Ruju (Người Tình Mùa Đông, Thuyền Tình Trên Sóng) 006 02- Koibito Yo (Hận Tình Trong Mưa, Tình Là Giấc Mơ) 022 03- Ribaibaru (Trời Còn Mưa Mãi, Tiễn Em Trong Mưa) 039 04- Ánh trăng nói hộ lòng tôi (Ánh trăng lẻ loi) 053 05- Hà Nhật Quân Tái Lai (Bao Giờ Chàng Trở Lại,. .) 067 06- Tsugunai (Tình chỉ là giấc mơ, Ước hẹn) 083 Phần II – Nhạc Phim 07- Dẫn Nhập 103 08- Eternally (Terry’s Theme, Limelight) 119 09- Que Será Será (Whatever will be, will be) 149 10- Ta Pedia tou Pirea /Never On Sunday) 166 11- The Green Leaves of Summer, Tiomkin & Webster 182 12- Moon River, Henri Mancini & Johnny Mercer 199 13- The Shadow of Your Smile, Johnny Mandel & . 217 14- Somewhere, My Love (Hỡi người tình Lara/Người yêu tôi đâu 233 15- A Time For Us (Tình sử Romeo & Juliet), 254 16- Where Do I Begin? Love Story, (Francis Lai & Carl Sigman) 271 17- The Summer Knows (Hè 42, Mùa Hè Năm Ấy) 293 18- Speak Softly, Love (Thú Đau Thương) 313 19- I Don’t Know How To Love Him (Chuyện Tình Xưa) 329 20- Thiên Ngôn Vạn Ngữ (Mùa Thu Lá Bay) 350 21- Memory (Kỷ Niệm) 369 22- The Phantom of the Opera (Bóng ma trong hí viện) 384 23- Unchained Melody (Tình Khúc Rã Rời,. -

Chuck Klosterman on Film and Television

Chuck Klosterman on Film and Television A Collection of Previously Published Essays Scribner New York London Toronto Sydney SCRIBNER A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 www.SimonandSchuster.com Essays in this work were previously published in Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs copyright © 2003, 2004 by Chuck Klosterman, Chuck Klosterman IV copyright © 2006, 2007 by Chuck Klosterman, and Eating the Dinosaur copyright © 2009 by Chuck Klosterman. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020. First Scribner ebook edition September 2010 SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work. For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1- 866-506-1949 or [email protected]. The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com. Manufactured in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-4516-2478-6 Portions of this work originally appeared in Esquire and on SPIN.com. Contents From Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs This Is Emo What Happens When People Stop Being Polite Being Zack Morris Sulking with Lisa Loeb on the Ice Planet Hoth The Awe-Inspiring Beauty of Tom Cruise’s Shattered, Troll-like Face How to Disappear Completely and Never Be Found From Chuck Klosterman IV Crazy Things Seem Normal, Normal Things Seem Crazy Don’t Look Back in Anger Robots Chaos 4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42 Television From Eating the Dinosaur “Ha ha,” he said. -

Top 10 Male Indian Singers

Top 10 Male Indian Singers 001asd Don't agree with the list? Vote for an existing item you think should be ranked higher or if you are a logged in,add a new item for others to vote on or create your own version of this list. Share on facebookShare on twitterShare on emailShare on printShare on gmailShare on stumbleupon4 The Top Ten TheTopTens List Your List 1Sonu Nigam +40Son should be at number 1 +30I feels that I have goten all types of happiness when I listen the songs of sonu nigam. He is my idol and sometimes I think that he is second rafi thumbs upthumbs down +13Die-heart fan... He's the best! Love you Sonu, your an idol. thumbs upthumbs down More comments about Sonu Nigam 2Mohamed Rafi +30Rafi the greatest singer in the whole wide world without doubt. People in the west have seen many T.V. adverts with M. Rafi songs and that is incediable and mind blowing. +21He is the greatest singer ever born in the world. He had a unique voice quality, If God once again tries to create voice like Rafi he wont be able to recreate it because God creates unique things only once and that is Rafi sahab's voice. thumbs upthumbs down +17Rafi is the best, legend of legends can sing any type of song with east, he can surf from high to low with ease. Equally melodious voice, well balanced with right base and high range. His diction is fantastic, you may feel every word. Incomparable. More comments about Mohamed Rafi 3Kumar Sanu +14He holds a Guinness World Record for recording 28 songs in a single day Awards *. -

Mapping the Aesthetical-Political Sonic, Master Thesis, © March 2017 Supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof

Universität für Künstlerische und Industrielle Gestaltung Linz Institut für Medien Interface Culture SOUNDSREVOLTING:MAPPINGTHE AESTHETICAL-POLITICALSONIC oliver lehner Master Thesis MA supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof. Dr. date of approbation: March 2017 signature (supervisor): Linz, 2017 Oliver Lehner: Sounds Revolting: Mapping the Aesthetical-Political Sonic, Master Thesis, © March 2017 supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof. Dr. location: Linz ABSTRACT I demand change. As a creator of sound art, I wanted to know what it can do. I tried to find out about the potential field in the overlap between a political aesthetic and a political sonic, between an artis- tic activism and sonic war machines. My point of entry was Steve Goodman’s Sonic Warfare. From there, trajectories unfolded through sonic architectures into an activist philosophy in interactive art. Sonic weapon technology and contemporary sound art practices define a frame for my works. In the end, I could only hint at sonic agents for change. iii CONTENTS i thesis 1 1 introduction 3 1.1 Why sound matters (to me) . 3 1.2 Listening for “New Weapons” . 4 1.3 Sounds of War . 5 1.4 Aesthetics and Politics . 6 2 acoustic weapons 11 2.1 On “Non-lethal” Weapons (NLW) . 11 2.2 A brief history of weaponized sound . 14 2.3 Sonic Battleground Europe . 19 2.4 Civil Sonic Weapons and Counter Measures . 20 3 the art of (sonic) war 23 3.1 Advanced Hyperstition: Goodman’s work after Sonic Warfare . 23 3.2 Artistic Sonic War Machines . 26 3.3 Ultrasound Art and Micropolitics of Frequency . 31 4 the search for sound artivism 37 4.1 Art and Activism .