The Evolution of Public Service Radio Broadcasting in Greece: from Authoritarianism to Anarchy and Irrelevance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy Panagiota Kaltsa

The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy 160 Packard Avenue, Medford, MA, 02155 Panagiota Kaltsa 102 Curtis Street, Somerville, MA 02144, USA Email: [email protected] Web: www.panagiotakaltsa.com Skype: panagiota.kaltsa 1 “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.” A. Einstein For my parents, Fotini and George, who gave me the opportunity to achieve my dreams 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Preface 6 Introduction 7 Thesis Outline Part I 12 Chapter I – Why Participation 13 Market for Loyalties 13 The market model 13 The national identity 15 The Greek case 16 The market 16 The Greek identity 18 The role of New Communication Technology in the Market for Loyalties 22 Regulation vs Participatory governance 26 Chapter II - Participation Theory 29 Definition of Participation 29 Research Method 31 Literature Review 32 Classification model 36 Transitioning from Vertical to Horizontal to Viral Participation 38 Participation Clusters 43 Vertical 43 Government 43 Corporate 47 Horizontal 51 Individual 51 Community 54 Cultural 60 Viral 61 Digital 61 Technological 71 Part II 74 Chapter III - Digital Participation Initiatives 75 Field Research findings 75 3 Code for America 76 Votizen 77 Active Voice 78 Lessons Learned 84 Chapter IV – Participation Communication Plan 86 E-governance: Benefits and Drawbacks 86 Benefits 84 Drawbacks 88 Communication Strategy 90 People 91 Objective 96 Strategy 97 Technology 101 Proposed Business Plan 107 Identifying the Problem 107 Suggested Organization Structure 108 Function 110 Conclusion 114 Moving Forward 114 Epilogue 116 Appendix 1: National and International Media Coverage analysis on 118 Greece in 2011 Appendix 2: Lincoln Toolkit 127 Appendix 3: Hellenic Statistic Service Graphs from Chapter 4 140 Bibliography 143 4 Executive Summary This work aims to set a framework for governments in crisis to strengthen their identity power and regain the trust of citizens, via participation and new communication technologies. -

ED394064.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 394 064 CE 071 463 AUTHOR Stavrou, Stavros TITLE Vocational Education and Training in Greece. INSTITUTION European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Thessaloniki (Greece). REPORT NO ISBN-92-826-8208-0 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 112p. AVAILABLE FROMUNIPUB, 4611-F Assembly Drive, Lanham, MD 20706-4391 (catalogue no. HX-81-93-793-EN-C: 14 European Currency Units). PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Education; Adult Education; Apprenticeships; Articulation (Education); Economic Change; Educational Change; Educational Finance; Educational Legislation; Educational Objectives; *Educational Policy; *Educational Practices; *Educational Trends; *Education Work Relationship; Elementary Secondary Education; Financial Support; Foreign Countries; Futures (of Society); Integrated Curriculum; *Job Training; Labor Market; Postsecondary Education; School Business Relationship; Tables (Data); Trend Analysis; *Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS European Community; *Greece ABSTRACT A study examined vocational education in Greece. First, vocational education was placed within the context of Greece's political and administrative structures and economy. The evolution of vocational education in Greece was traced. The structure, objectives, and delivery of general education and initial and further vocational education were outlined along with the institutional and financial contexts of the Greek vocational system. Trends and future prospects in Greece were identified/discussed. -

Shortwave-Listener's

skï.. Radio lhaek TWO DOLLARS AND TWENTY—FIVE CENTS 62-2032 Shortwave Listener's Guide by H. Charles Woodruff Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. 4300 WEST 62ND ST. INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46268 USA Copyright 0 1964, 1966, 1968, 1970, 1973, 1976, and 1980 by Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 EIGHTH EDITION FIRST PRINTING-1980 All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the information contained herein. While every pre- caution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. International Standard Book Number: 0-672-21655-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-67132 Printed in the United States of America. Preface Every owner of a shortwave receiving set is familiar with the thrill that comes from hearing a distant station broadcasting from a foreign country. To hundreds of thousands of people the world over, short- wave listening (often referred to as swl) represents the most satisfy- ing, the most worthwhile of all hobbies. It has been estimated that more than 25 million shortwave receivers are in the hands of the American public, with the number increasing daily. To explore the international shortwave broadcasting bands in a knowledgeable manner, the shortwave listener must have available a list of shortwave stations, their frequencies, and their times of trans- mission. -

3 DX MAGAZINE No. 2

2 - 2004 All times mentioned in this DX MAGAZINE are UTC - Alle Zeiten in diesem DX MAGAZINE sind UTC Staff of WORLDWIDE DX CLUB: PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EDITOR ..C WWDXC Headquarters, Michael Bethge, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany B daytime +49-6102-2861, B evening/weekend +49-6172-390918 F +49-6102-800999 V E-Mail: [email protected] BROADCASTING NEWS EDITOR . C Dr. Jürgen Kubiak, Goltzstrasse 19, D-10781 Berlin, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] LOGBOOK EDITOR .............C Ashok Kumar Bose, Apt. #421, 3420 Morning Star Drive, Mississauga, ON, L4T 1X9, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] QSL CORNER EDITOR ..........C Richard Lemke, 60 Butterfield Crescent, St. Albert, Alberta, T8N 2W7, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] TOP NEWS EDITOR (Internet) ....C Wolfgang Büschel, Hoffeld, Sprollstrasse 87, D-70597 Stuttgart, Germany V E-Mail: [email protected] TREASURER & SECRETARY .....C Karin Bethge, Urseler Strasse 18, D-61348 Bad Homburg, Germany NEWCOMER SERVICE OF AGDX . C Hobby-Beratung, c/o AGDX, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany (please enclose return postage) Each of the editors mentioned above is self-responsible for the contents of his composed column. Furthermore, we cannot be responsible for the contents of advertisements published in DX MAGAZINE. We have no fixed deadlines. Contributions may be sent either to WWDXC Headquarters or directly to our editors at any time. If you send your contributions to WWDXC Headquarters, please do not forget to write all contributions for the different sections on separate sheets of paper, so that we are able to distribute them to the competent section editors. -

European Citizen Information Project FINAL REPORT

Final report of the study on “the information of the citizen in the EU: obligations for the media and the Institutions concerning the citizen’s right to be fully and objectively informed” Prepared on behalf of the European Parliament by the European Institute for the Media Düsseldorf, 31 August 2004 Deirdre Kevin, Thorsten Ader, Oliver Carsten Fueg, Eleftheria Pertzinidou, Max Schoenthal Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Executive Summary 5 Part I Introduction 8 Part II: Country Reports Austria 15 Belgium 25 Cyprus 35 Czech Republic 42 Denmark 50 Estonia 58 Finland 65 France 72 Germany 81 Greece 90 Hungary 99 Ireland 106 Italy 113 Latvia 121 Lithuania 128 Luxembourg 134 Malta 141 Netherlands 146 Poland 154 Portugal 163 Slovak Republic 171 Slovenia 177 Spain 185 Sweden 194 United Kingdom 203 Part III Conclusions and Recommendations 211 Annexe 1: References and Sources of Information 253 Annexe 2: Questionnaire 263 2 Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to the following people for their assistance in preparing this report, and its translation, and also those national media experts who commented on the country reports or helped to provide data, and to the people who responded to our questionnaire on media pluralism and national systems: Jean-Louis Antoine-Grégoire (EP) Gérard Laprat (EP) Kevin Aquilina (MT) Evelyne Lentzen (BE) Péter Bajomi-Lázár (HU) Emmanuelle Machet (FR) Maria Teresa Balostro (EP) Bernd Malzanini (DE) Andrea Beckers (DE) Roberto Mastroianni (IT) Marcel Betzel (NL) Marie McGonagle (IE) Yvonne Blanz (DE) Andris Mellakauls (LV) Johanna Boogerd-Quaak (NL) René Michalski (DE) Martin Brinnen (SE) Dunja Mijatovic (BA) Maja Cappello (IT) António Moreira Teixeira (PT) Izabella Chruslinska (PL) Erik Nordahl Svendsen (DK) Nuno Conde (PT) Vibeke G. -

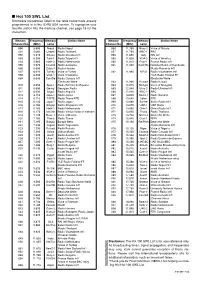

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Federal Communications Commission Enforcement Bureau Office of the Field Director

Federal Communications Commission Enforcement Bureau Office of the Field Director 45 L Street, NE Washington, DC 20554 [email protected] December 17, 2020 BY FIRST-CLASS MAIL AND CERTIFIED MAIL BRG 3512 LLC KRR Queens 1 LLC BRG Management LLC 150 Great Neck Road, Suite 402 Great Neck, New York 11021 ATTN: Jonah Rosenberg NOTICE OF ILLEGAL PIRATE RADIO BROADCASTING Case Number: EB-FIELDNER-17-00024174 The New York Office of the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Enforcement Bureau is investigating a complaint about an unlicensed FM broadcast station operating on the frequency 95.9 MHz. On November 14, 2020, agents from the New York Office confirmed by direction-finding techniques that radio signals on frequency 95.9 MHz were emanating from the property at 3512 99th Street, Queens, New York. Publicly available records identify BRG 3512 LLC and KRR Queens 1 LLC as joint owners of the property at 3512 99th Street, Queens, New York, and BRG Management LLC as the site’s property manager.1 The FCC’s records show no license issued for operation of a radio broadcast station on 95.9 MHz at that location. Radio broadcast stations operating on certain frequencies,2 including 95.9 MHz, must be licensed by the FCC pursuant to the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (Act).3 While the FCC’s rules create exceptions for certain extremely low-powered devices, our agents have determined that those exceptions do not apply to the transmissions they observed originating from the property. Accordingly, the station operating on the property identified above -

Drama Directory

2015 UPDATE CONTENTS Acknowlegements ..................................................... 2 Latvia ......................................................................... 124 Introduction ................................................................. 3 Lithuania ................................................................... 127 Luxembourg ............................................................ 133 Austria .......................................................................... 4 Malta .......................................................................... 135 Belgium ...................................................................... 10 Netherlands ............................................................. 137 Bulgaria ....................................................................... 21 Norway ..................................................................... 147 Cyprus ......................................................................... 26 Poland ........................................................................ 153 Czech Republic ......................................................... 31 Portugal ................................................................... 159 Denmark .................................................................... 36 Romania ................................................................... 165 Estonia ........................................................................ 42 Slovakia .................................................................... 174 -

Bulletin of the DANISH SHORT WAVE CLUB INTERNATIONAL for Short Wave Listeners and Dxers No 9 December 2009 Volume 52

Bulletin of the DANISH SHORT WAVE CLUB INTERNATIONAL for short wave listeners and DXers No 9 December 2009 Volume 52 Our German member, no. 3700 Dieter Sommer The equipment is Yaesu FT840, Sangean ATS-909 modifed, a T2FD antenna and a GP horizontal antenna. Dieter writes that he prefers Utility, Pirate and BC DX-ing Dieter has more than 200 countries verified He is 56 years old and have been DX-ing in about 43 years Editorial Staff: ISSN 0106-3731 Danish Short Wave Club International Shortwave Tips: Tavleager 31, DK-2670 Greve, Denmark Klaus-Dieter Scholz, Home page: http://www.dswci.org Postfach 45 02 34, D-99052 Erfurt, Germany Board: Tel.: +49 (0)361 –- 21 68 96 5, Fax: +49(0) 69 - 13 30 63 72 07 8 Chairman and representative to the EDXC: Web::http://www.dswci-sw-logs.dxer.info/yourlogs.htm Anker Petersen, E-mail: [email protected] Udbyvej 11, DK-2740 Skovlunde, Denmark Utility Shack: E-mail: [email protected] Tor-Henrik Ekblom, Treasurer: Solvindsgatan 7 A 20, FI-00990 Helsingfors, Finland Bent Nielsen, E-mail: [email protected] Egekrogen 14, DK-3500 Vaerloese, Denmark World News: E-mail: [email protected] Sakthi Jaisakthivel, Bank: Danske Bank, 59,Annai Sathya Nagar, Arumbakkam, Chennai-600106,India.: Holmens Kanal 2-12, DK 1092 Copenhagen K. E-mail:[email protected] BIC: DABADKKK. Account: DK 44 3000 4001 528459. QSL Corner: Danish members use: Reg. 3001- account no. 4001528459 Andreas Schmid, The treasurer accepts bank notes! Lerchenweg 4, D-97717 Euerdorf, Germany Editor-in-Chief and Distribution: E-mail: [email protected] Kaj Bredahl Jørgensen, Tel. -

Making Radio Pirates Walk the Plank with Aiding and Abetting Liability

Arrr! Sever Thee Transmitters! Making Radio Pirates Walk the Plank with Aiding and Abetting Liability Max Nacheman * TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 299 II. THE INTERTWINED FATE OF BROADCAST REGULATION AND PIRATE RADIO ............................................................................................. 301 A. Origins of Radio Broadcast Regulation in the United States .. 301 B. Pirates of the (Air)waves: The Swell of Unauthorized Broadcasting ............................................................................ 303 C. From Radio Pirates to Cellular Ninjas: The Future of Unauthorized Broadcasting ..................................................... 304 III. UNAUTHORIZED BROADCASTING POSES A UNIQUE ENFORCEMENT CHALLENGE THAT MAY BE ADDRESSED BY ESTABLISHING AUTHORITY TO CRACK DOWN ON AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF PIRATE BROADCASTERS .............................................................................. 305 A. The FCC’s Enforcement Procedure for Unauthorized Broadcasters Is an Inadequate Deterrent to Pirates ............... 306 B. Aiding and Abetting Liability Would Cut the Supply Chain of Essential Resources to Unauthorized Broadcasters ................ 309 1. How the United Kingdom Sank Pirate Radio ................... 310 2. Aiding and Abetting Liability for Securities Violations ... 311 IV. THREE WAYS TO CRACK DOWN ON AIDERS AND ABETTORS OF UNAUTHORIZED BROADCASTING: STATUTE, RULEMAKING, AND EXISTING CRIMINAL LAW ............................................................. -

Must-Carry Rules, and Access to Free-DTT

Access to TV platforms: must-carry rules, and access to free-DTT European Audiovisual Observatory for the European Commission - DG COMM Deirdre Kevin and Agnes Schneeberger European Audiovisual Observatory December 2015 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction and context of study 7 Executive Summary 9 1 Must-carry 14 1.1 Universal Services Directive 14 1.2 Platforms referred to in must-carry rules 16 1.3 Must-carry channels and services 19 1.4 Other content access rules 28 1.5 Issues of cost in relation to must-carry 30 2 Digital Terrestrial Television 34 2.1 DTT licensing and obstacles to access 34 2.2 Public service broadcasters MUXs 37 2.3 Must-carry rules and digital terrestrial television 37 2.4 DTT across Europe 38 2.5 Channels on Free DTT services 45 Recent legal developments 50 Country Reports 52 3 AL - ALBANIA 53 3.1 Must-carry rules 53 3.2 Other access rules 54 3.3 DTT networks and platform operators 54 3.4 Summary and conclusion 54 4 AT – AUSTRIA 55 4.1 Must-carry rules 55 4.2 Other access rules 58 4.3 Access to free DTT 59 4.4 Conclusion and summary 60 5 BA – BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 61 5.1 Must-carry rules 61 5.2 Other access rules 62 5.3 DTT development 62 5.4 Summary and conclusion 62 6 BE – BELGIUM 63 6.1 Must-carry rules 63 6.2 Other access rules 70 6.3 Access to free DTT 72 6.4 Conclusion and summary 73 7 BG – BULGARIA 75 2 | Page 7.1 Must-carry rules 75 7.2 Must offer 75 7.3 Access to free DTT 76 7.4 Summary and conclusion 76 8 CH – SWITZERLAND 77 8.1 Must-carry rules 77 8.2 Other access rules 79 8.3 Access to free DTT -

Annual Report 2007

1 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Personal thoughts and feelings of real people. A random moment of your life on a piece of paper. Drawings, forms and colors representing joy, anger, fullfilment, loneliness, silence, cries, anything. You need to express yourself and the urge you have to communicate. This is what makes our work worthwhile and this is the message of this report. You. THE ΟΤΕ GROUP WHO: STELIOS WHEN: SATURDAY WHERE: ATHENS WHO: VASSILIKI WHEN: ΤUESDAY WHERE: ΤΟΚIΟ WHO: MANOS WHEN: FRIDAY WHERE: ATHENS THE OTE GROUP 12 THE OTE GROUP ROMANIA SERBIA BULGARIA FYROM ALBANIA GREECE THE OTE GROUP 13 GREECE Fixed-line and mobile telephony Fixed-line subscribers: 5,854,000 ADSL subscribers: 825,000 Mobile telephony subscribers: 6,269,000 ROMANIA Shareholder Structure Fixed-line and mobile telephony May 15, 2008 Fixed-line subscribers: 3,035,000 35.3% ADSL subscribers: 360,000 International Institutional Investors Mobile telephony subscribers: 3,616,000 BULGARIA 28.0% Mobile telephony Hellenic State Subscribers: 3,873,000 20.0% ALBANIA Deutsche Telekom Mobile telephony Subscribers: 1,195,000 FYROM 9.8% Mobile telephony Greek Institutional Investors Subscribers: 593,000 6.8% Other Since 2006, the OTE Group owns 90% of GERMANOS S.A., the largest distributor of technology-related products in Southeast Europe with 769 stores. SERBIA Fixed-line and mobile telephony OTE owns 20% of Telekom Srbija THE OTE GROUP 14 GROUP STRUCTURE Fixed-Line Telephony Mobile Telephony OTE SA 100% ΟΤΕGLOBE Greece Greece Other Operations 100% ΟΤΕNET Greece 100% 54% Cosmote RomTelecom 100% ΟΤΕestate Greece Romania Greece AMC 82% 100% Globul 99% Hellas Sat Albania Bulgaria Greece Cosmofon 100% 70% Cosmote Romania 94% ΟΤΕSat-Maritel FYROM Romania Greece 90% Germanos 100% ΟΤΕplus S.E.