Thompson Punk Productions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

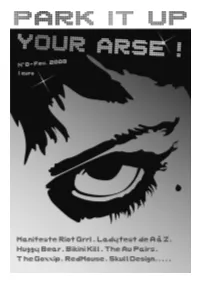

Maquette Park It Up.Qxd

RIOT GRRRL IS NOT DEAD... Phrase choc pour un premier zine qui ne fera certainement pas l’unanimité… Mouvement culturel « éphémère » sans avenir selon les médias de l’époque, mais dont l’influence et l’inspiration sont toujours d’actualité dans ce milieu majoritairement masculin. A force de réflexion, de discussions mais surtout de frustrations et d’agace- ment ; d’a priori, de préjugés ainsi que de pseudo concurrents au titre de meilleur militant anti-sexiste de l’an- née, ce zine aura vu le jour. Mon objectif : vous faire entrer, toutes et tous, un peu dans ce monde obscur appelé communément « riot grrrl », culturellement riche, provocateur néanmoins, existant de par la solidarité qui l’anime. Ouvrir la porte sur la vie de toutes ces filles de la contre culture qui se battent au jour le jour pour elles aussi faire leur place, mettre en lumière leur travail et mettre en mots tout le reste. « Park it up your arse » inspiré de la chanson des Headcoatees du même nom, qui se traduit littéralement signifie « gare le dans ton cul ». D’une pierre deux coups, c’est ma réponse à ceux qui me diront que ce zine est sans intérêt, aux « grands chroniqueurs » de zine qui parfois semblent oublier que rien n’est parfait, que l’intérêt d’un zine réside en l’intérêt qu’on porte au sujet. Ce premier numéro a été long et laborieux et, j’avoue, loin d’être assez complet. Cette ébauche garde donc l’essentiel, culture générale, musique, DIY ; le compromis entre l’envie et le maté- riel pour écrire un livre et la volonté de présenter le mouvement Riot Grrrl et les initiatives parfois marginales et méconnues de la scène punk, féministe, lesbienne-gay-bi-trans-queer (LBGTQ). -

Scenes from a Punk Rock and Storytelling Show, for Deaf People by NATHAN REESE APRIL 29, 2016

Scenes From a Punk Rock and Storytelling Show, for Deaf People By NATHAN REESE APRIL 29, 2016 At its best, punk rock relies on an admixture of velocity, attitude and volume —which is exactly what made last night’s Deaf Club event a smash success. The show, held at the Knockdown Center in Maspeth, Queens, a former door factory turned interdisciplinary arts space, was curated by the Los Angeles- based artist Alison O’Daniel who, herself, is hard of hearing. The event was a live extension of O’Daniel’s “The Tuba Thieves” (currently a part of her “Room Tone” exhibition) — a film that explores the events surrounding an unlikely series of tuba thefts in Los Angeles schools. One portion, however, also recreates a performance in the Deaf Club, a now-defunct social club for San Francisco’s deaf community that hosted punk shows in 1979. As the story goes, Robert Hanrahan, the manager for the punk band the Offs, was walking by it, saw a sign reading “The Deaf Club” and thought it was a cool, unexpected name for a concert venue. After realizing his mistake, he asked if his band could play — a message he originally wrote on a napkin. “I’m not a punk historian,” said O’Daniel. “My interest comes more from the deaf community. It’s the meeting of two totally disenfranchised communities — it’s really beautiful.” Eventually, bands including Dead Kennedys and Pink Section would record albums at the venue, forever sanctifying it in punk lore. (A core irony of the story, and also fittingly punk, was that the shows eventually came to a halt because of noise complaints.) But the goal of last night’s event wasn’t an attempt to dispel hearing people’s outmoded assumption that the deaf world doesn’t (or can’t) appreciate music — though that notion seemed ready to explode along with the tower of amps — but rather, to create an environment where people of all ages and backgrounds could revel in the power of punk and performance art. -

SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music

Page 1 The San Diego Union-Tribune October 1, 1995 Sunday SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music By Daniel de Vise KNIGHT-RIDDER NEWSPAPERS DATELINE: LOS ALAMITOS, CALIF. Ten years ago, when SST Records spun at the creative center of rock music, founder Greg Ginn was living with six other people in a one-room rehearsal studio. SST music was whipping like a sonic cyclone through every college campus in the country. SST bands criss-crossed the nation, luring young people away from arenas and corporate rock like no other force since the dawn of punk. But Greg Ginn had no shower and no car. He lived on a few thousand dollars a year, and relied on public transportation. "The reality is not only different, it's extremely, shockingly different than what people imagine," Ginn said. "We basically had one place where we rehearsed and lived and worked." SST, based in the Los Angeles suburb of Los Alamitos, is the quintessential in- dependent record label. For 17 years it has existed squarely outside the corporate rock industry, releasing music and spoken-word performances by artists who are not much interested in making money. When an SST band grows restless for earnings or for broader success, it simply leaves the label. Founded in 1978 in Hermosa Beach, Calif., SST Records has arguably produced more great rock bands than any other label of its era. Black Flag, fast, loud and socially aware, was probably the world's first hardcore punk band. Sonic Youth, a blend of white noise and pop, is a contender for best alternative-rock band ever. -

Komplette Ausgabe Als

TRUST * ES IST WAHR ! 'JL. DIE NATUR IST GRAUSAM! DER MENSCH IST SCHLECHT! Aber wir, wir k sind gut, wir sind nett und wir sind lieb, denn wir machen euch ein Weihnachtsgeschenk. Beim Fest der großen Heucheleien machen wir euch ein Geschenk, das von HERZEN kommt, ein Geschenk ohne jegliche Hintergedanken, ein Geschenk, das ohr nie vergessen werdet, ein ehrliches, ein wertvolles, ein schönes Geschenk. Nun liegt es vor euch, in Form einer Flexi, nehmt sie vorsichtig hier ab und gebt euch dem Hörgenuß hin! Aber nein nicht doch vor Rührung weinen, heute sollen alle glück- lich sein, auch ihr! AMEN! JINGO DE LUNCH ft i What You See what you see i know it makes no difference to me and if c p o w n o f you could see through my eyes see through my eyes i still could'nt t rust what you say is aggression all you're looking for what i see ju st is'nt the same thousand storys reach my ears decide what you see. IS O L Re M AT E O but they can't change my opinions changing viewpoints promoting fear what you see seeing blind repeting a tension i still could'nt trust, what you say if you've got nothing to do but slander then you've got nothing to say it has nothing to do with me what you see i don't wan lìoone can stop us t to fuse with your opinions and if you want to use ok. i think i've RUN ROUND IN' A CIRCLE caught a double vision look through my eyes what do you see it is'nt DANCE AS CRAZY AS YOU CAN' the same what i see trusting you trusting me where is the truth wher RUN ROUND IN A CIRCLE e did it go where did it go where did it go? 2'07" SO T11AT EVERYONE CAN SEE YOU SHOW THEM THAT YOU 3EL0NG TOGETHER AND THAT NOBODY CAN STOP YOUR CIRCLE DANCE RUN ROUND IN A CIRCLE ^ DANCE................. -

California Noise: Tinkering with Hardcore and Heavy Metal in Southern California Steve Waksman

ABSTRACT Tinkering has long figured prominently in the history of the electric guitar. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, two guitarists based in the burgeoning Southern California hard rock scene adapted technological tinkering to their musical endeavors. Edward Van Halen, lead guitarist for Van Halen, became the most celebrated rock guitar virtuoso of the 1980s, but was just as noted amongst guitar aficionados for his tinkering with the electric guitar, designing his own instruments out of the remains of guitars that he had dismembered in his own workshop. Greg Ginn, guitarist for Black Flag, ran his own amateur radio supply shop before forming the band, and named his noted independent record label, SST, after the solid state transistors that he used in his own tinkering. This paper explores the ways in which music-based tinkering played a part in the construction of virtuosity around the figure of Van Halen, and the definition of artistic ‘independence’ for the more confrontational Black Flag. It further posits that tinkering in popular music cuts across musical genres, and joins music to broader cultural currents around technology, such as technological enthusiasm, the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, and the use of technology for the purposes of fortifying masculinity. Keywords do-it-yourself, electric guitar, masculinity, popular music, technology, sound California Noise: Tinkering with Hardcore and Heavy Metal in Southern California Steve Waksman Tinkering has long been a part of the history of the electric guitar. Indeed, much of the work of electric guitar design, from refinements in body shape to alterations in electronics, could be loosely classified as tinkering. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Brevard Live Live March 2020

Brevard Live Live March 2020 - 1 2 - Brevard Live March 2020 Brevard Live Live March 2020 - 3 4 - Brevard Live March 2020 Brevard Live Live March 2020 - 5 6 - Brevard Live March 2020 Contents March 2020 FEATURES HOT PINK INDIAFEST Hot Pink has made a name for them- Columns Royal West India is the theme of this selves, not just as a good band but also Charles Van Riper year’s Indiafest held in Wickham Park. as great entertainers. One of the best It is a symbol of cultural enrichment in 22 Political Satire showmen in Brevard is vocalist James Dollar To Doghnuts Brevard and is celebrated with great en- Spiva who is also an actor. Matt Bretz thusiasm. got with Spiva for an in-depth interview. Page 11 Calendars Page 14 25 Live Entertainment, SOUND WAVES MUSIC FESTIVAL Concerts, Festivals This is the 4th annual Sound Waves Mu- GREG REINEL sic Festival held by 89.5 FM WFIT. The Reinel’s passion for art and music grew Brevard Love radio station features the winner of their as a young adult. The Screaming Igua- 30 by Matt Bretz garage band contest along with a nice nas of Love were one of the first Mel- Human Satire line-up of other bands. bourne based bands he was part of. But Page 12 it was his poster art that made him world Local Lowdown famous. 32 by Steve Keller BEERAPALOOZA Page 18 Beerapalooza is the first big event in CD Review 2020 held at Florida Beer Company in JAIMIE ENGLE 35 by Rob Pedrick Cape Canaveral. -

Family Album

1 2 Cover Chris Pic Rigablood Below Fabio Bottelli Pic Rigablood WHAT’S HOT 6 Library 8 Rise Above Dead 10 Jeff Buckley X Every Time I Die 12 Don’t Sweat The Technique BACKSTAGE 14 The Freaks Come Out At Night Editor In Chief/Founder - Andrea Rigano Converge Art Director - Alexandra Romano, [email protected] 16 Managing Director - Luca Burato, [email protected] 22 Moz Executive Producer - Mat The Cat E Dio Inventò... Editing - Silvia Rapisarda 26 Photo Editor - Rigablood 30 Lemmy - Motorhead Translations - Alessandra Meneghello 32 Nine Pound Hammer Photographers - Luca Benedet, Mattia Cabani, Lance 404, Marco Marzocchi, 34 Saturno Buttò Alex Ruffini, Federico Vezzoli, Augusto Lucati, Mirko Bettini, Not A Wonder Miss Chain And The Broken Heels - Tour Report Boy, Lauren Martinez, 38 42 The Secret Illustrations - Marcello Crescenzi/Rise Above 45 Jacopo Toniolo Contributors - Milo Bandini, Maurice Bellotti/Poison For Souls, Marco Capelli, 50 Conkster Marco De Stefano, Paola Dal Bosco, Giangiacomo De Stefano, Flavio Ignelzi, Brixia Assault Fra, Martina Lavarda, Andrea Mazzoli, Eros Pasi, Alex ‘Wizo’, Marco ‘X-Man’ 58 Xodo, Gonz, Davide Penzo, Jordan Buckley, Alberto Zannier, Michele & Ross 62 Family Album ‘Banda Conkster’, Ozzy, Alessandro Doni, Giulio, Martino Cantele 66 Zucka Vs Tutti Stampa - Tipografia Nuova Jolly 68 Violator Vs Fueled By Fire viale Industria 28 Dear Landlord 35030 Rubano (PD) 72 76 Lagwagon Salad Days Magazine è una rivista registrata presso il Tribunale di Vicenza, Go Getters N. 1221 del 04/03/2010. 80 81 Summer Jamboree Get in touch - www.saladdaysmag.com Adidas X Revelation Records [email protected] 84 facebook.com/saladdaysmag 88 Highlights twitter.com/SaladDays_it 92 Saints And Sinners L’editore è a disposizione di tutti gli interessati nel collaborare 94 Stokin’ The Neighbourhood con testi immagini. -

Shit | Search Results | the Enquirer the Enquirer

shit | Search Results | The Enquirer The Enquirer Search results You searched for shit p ~ Posted on August 26, 2015` Safe Interviews w/ Zack and Porcell. No Need to Be Suspicious. had a week or two before Ray would show up in San Diego, so I mostly I holed-up in my room upstairs and put together the fourth issue of Enquirer. The main features were interviews with Zack and Porcell. I see these as the first noticeable examples of what would become a rather nasty habit for me as the zine’s editor: bending words to obscure points I didn’t like and favor points I did like. https://vicd108.wordpress.com/?s=shit[9/10/15, 3:25:18 PM] shit | Search Results | The Enquirer For example, I report Zack as saying: “I think leading a spiritual life means casting away and putting aside the physical nature in life, and the intellectual nature in life. But actually it’s using all three of them… And spirituality… Follow like…” Follow “The Enquirer” What kind of editing is that? Get every new post delivered to your Inbox. Knowing Zack, and having the benefit of hearing his voice directly, it was pretty obvious toJoin me 612 what other he followerswanted to say: that spiritual life isn’t something you have to throw away your material life for; that the two can and should be integrated, complimentary, and mutually nourishing. If I was actually editing to make the point Zack wanted to make, I would have written it like this: “I don’t think ‘leading a spiritual life’ means you have to cast aside the physical and intellectual aspects life. -

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

Download Download

CRITICAL COMMENTARY Crip Club Vibes: Technologies for New Nightlife Kevin Gotkin New York University [email protected] I’ve been thinking about what it would mean to design nightlife around disability. We need all nightlife spaces to become accessible, of course, something that calls for a thoroughgoing restructuring of the built environment, transportation systems, and access labor. But I’m imagining the possibilities for creating a world within the inaccessible status quo, a nightlife community that could divine the truth and complexity of disability history, culture, and resistance. When I ask my disability community in New York City about nightlife, I get a series of sighs. Nightlife is exhausting. That’s not because being disabled in nightlife spaces is in itself exhausting. It’s exhausting because ableism is exhausting and because nightlife is a nexus of many inaccessible cultural forms that make parties, clubs, and bars feel like one marathon after another. We don’t often think of nightlife as a technology itself, but we should. It’s hard to decide the status of nightlife in basic terms: Is it a community? An industry? A social function? If we take up the call in the manifesto that inspires this special issue, we can locate nightlife within the “non-compliant knowing-making” of crip technoscience that relishes the world-making possibilities for disabled living (Fritsch & Hamraie, 2019). Technoscientific Gotkin, K. (2019). Crip club vibes: Technologies for new nightlife. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 5 (1), 1-7. http://www.catalystjournal.org | ISSN: 2380-3312 © Kevin Gotkin, 2019 | Licensed to the Catalyst Project under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license Gotkin Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 5(1) 2 protocols for thinking about nightlife offer what has traditionally been absent: deliberation, design, and aesthetics as a toolkit for shaping our collective imaginations and desires.