The Department of English Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Maryallenfinal Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SIX IMPOSSIBLE THINGS BEFORE BREAKFAST: THE LIFE AND MIND OF LEWIS CARROLL IN THE AGE OF ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND MARY ALLEN SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Kate Rosenberg Assistant Teaching Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Christopher Reed Distinguished Professor of English, Visual Culture, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes and offers connections between esteemed children’s literature author Lewis Carroll and the quality of mental state in which he was perceived by the public. Due to the imaginative nature of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it has been commonplace among scholars, students, readers, and most individuals familiar with the novel to wonder about the motive behind the unique perspective, or if the motive was ever intentional. This thesis explores the intentionality, or lack thereof, of the motives behind the novel along with elements of a close reading of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. It additionally explores the origins of the concept of childhood along with the qualifications in relation to time period, culture, location, and age. It identifies common stereotypes and presumptions within the subject of mental illness. It aims to achieve a connection between the contents of Carroll’s novel with -

Lewis Carroll (Charles L

LEWIS CARROLL (CHARLES L. DODGSON) a selection from The Library of an English Bibliophile Peter Harrington london VAT no. gb 701 5578 50 Peter Harrington Limited. Registered office: WSM Services Limited, Connect House, 133–137 Alexandra Road, Wimbledon, London SW19 7JY. Registered in England and Wales No: 3609982 Design: Nigel Bents; Photography Ruth Segarra. Peter Harrington london catalogue 119 LEWIS CARROLL (CHARLES L. DODGSON) A collection of mainly signed and inscribed first and early editions From The Library of an English Bibliophile All items from this catalogue are on display at Dover Street mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 Dover Street 100 Fulham Road London w1s 4ff London sw3 6hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 Dover St opening hours: 10am–7pm Monday–Friday; 10am–6pm Saturday www.peterharrington.co.uk FOREWORD In 1862 Charles Dodgson, a shy Oxford mathematician with a stammer, created a story about a little girl tumbling down a rabbit hole. With Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), children’s literature escaped from the grimly moral tone of evangelical tracts to delight in magical worlds populated by talking rabbits and stubborn lobsters. A key work in modern fantasy literature, it is the prototype of the portal quest, in which readers are invited to follow the protagonist into an alternate world of the fantastic. The Alice books are one of the best-known works in world literature. They have been translated into over one hundred languages, and are referenced and cited in academic works and popular culture to this day. -

The Multifaceted Life of Lewis Carroll

For Immediate Release 29 October 2005 Contact: Zoë Schoon 020.7752.3121 [email protected] THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS: THE MULTIFACETED LIFE OF LEWIS CARROLL “The more I read, the more impressed I became. The real testament to Carroll’s genius is that after a century and a half, he is still held in the highest esteem by an ever-growing audience of young and old, novice and scholar, logician and lover of nonsense”. Nicholas Falletta The Nicholas Falletta Collection of Lewis Carroll Books and Manuscripts Wednesday 30 November at 2.00pm South Kensington – One of the most considered and thoughtfully-assembled collections of Lewis Carroll material, The Nicholas Falletta Collection of Lewis Carroll Books and Manuscripts will be offered at Christie’s South Kensington on 30 November 2005. Comprising in excess of 120 lots, the sale illuminates the life and personality of this remarkable, many-talented man who wrote some of the best-loved childrens’ books in the English language. Featuring first editions, personal letters, original illustrations, books owned by Carroll, or given by him to his friends (both young and old), rare mathematical textbooks, and little-known games and puzzles, the collection is estimated to fetch in excess of £300,000. Mathematical beginnings… Lewis Carroll was born Charles Lutwidge Dodgson in January 1832. He graduated from Christ Church, Oxford in 1854 with a BA Honours in Mathematics and Classics. Elected to a life fellowship, he continued to lecture at Oxford and publish mathematical broadsheets to help his students. It was during this time that he created his famous pseudonym by taking “Charles” and “Lutwidge”, and inverting the latinised form to create “Lewis Carroll”. -

ON CENSORSHIP • We Can Work It

VOL 47, NO. 3 JULY 2009 A JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S LITERATURE ON CENSORSHIP • We Can Work It Out: Challenge, Debate and Acceptance • Picturing the Prophets; Should Art Create Doubt? • Sex and Violence in Fairy Tales for Children • Hidden Forms of Censorship and Their Impact • Peter Sís: A Quest for a Life in Truth • My Life with Censorship • Behind the Wall under the Red Star I N E T E R P L N A T E O I O N A P L B O O U N G A R D O N B O O K S F O R Y Bby A JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S LITERATURE The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Copyright © 2009 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Editors: Catherine Kurkjian & Sylvia Vardell Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by Central Connecticut State University, New Britain, CT USA. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Emy Beseghi (Italy), Ernest Bond (USA), Penni Cotton (UK), Nancy Hadaway (USA), Erica Hateley (Australia), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Janet Hilbun (USA), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), June Jacko (USA), Nadia El Kholy (Egypt), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Chloe Mauger (Australia), Lissa Paul (USA), Mudite Treimane (Latvia), Liz Thiel (UK), Ira Saxena (India), Deborah Soria (Italy), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Anna Karlskov Skyggebjerg (Denmark), Jochen Weber (Germany), Terrell A. Young (USA), Guest Reviewer; Helen R. Abadiano (USA) Board of Bookbird, Inc. -

OPEN SEASON on SNARKS Pens

234 A Beaver OPEN SEASON ON SNARKS pens. and beavers: : A Banker in his carl raising ev A. voRPAL PENN* In 11 Jabbe: Greetings of t 11 II His form is ungainly -- his intellect small (So the Bellman would often remark) - Salutation II But his courage is perfect! And that, after all, Is the thing that one needs with a Snark, II -- The Hunting of the Snark Valedictio In a whimsicalogical treatise entitled loIFor a Lewis Carroll Soci ety" in the November 1969 Word Ways, the present writer proposed It has beel that a call be issued to all serious Lewis Carroll students and funny im might include itators to form a society for the hunting of Literary Snarks. A Literary confused with Snark was defined as a OlesHon. Observation, Speculation, Contradic Lingua in Buc tion' Ilnitation or Invention about, on, concerning, in, of, or based up on the writings of Lewis Carroll. Several typical specimens were ex hibited. with a particular provi s ion being made fa r a das s of Non Snarks. It was suggested that the proposed society be called The Bold Snark No. On, Order of Snark Hunters (BOSH) , and that it be run along the lines of the Menai Bridge. Martin Gardner 1 s two full bags of Snarks, The An In my 196 notated Alice and The Annotated Snark, were earnestly comITlended to John Tenniel \ readers, and those interested in the whole project were invited to youthful figur, write to ITle c/o Word Ways. Alice ?" There having been no response, I have had more time free for fur It is now I ther Snark hunts of ITly own. -

Tekan Bagi Yang Ingin Order Via DVD Bisa Setelah Mengisi Form Lalu

DVDReleaseBest 1Seller 1 1Date 1 Best4 15-Nov-2013 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 1 1-Dec-2014 1 Seller 1 2 1 Best1 1 30-Nov-20141 Seller 1 6 2 Best 4 1 9 Seller29-Nov-2014 2 1 1 1Best 1 1 Seller1 28-Nov-2014 1 1 1 Best 1 1 9Seller 127-Nov-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 326-Nov-2014 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 1 25-Nov-20141 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 24-Nov-2014Best1 1 1 Seller 1 2 1 1 Best23-Nov- 1 1 1Seller 8 1 2 142014Best 3 1 Seller22-Nov-2014 1 2 6Best 1 1 Seller2 121-Nov-2014 1 2Best 2 1 Seller8 2 120-Nov-2014 1Best 9 11 Seller 1 1 419-Nov-2014Best 1 3 2Seller 1 1 3Best 318-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 17-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 1 1 Best 1 1 16-Nov-20141Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 15-Nov-2014 1 1 1Best 2 1 Seller1 1 14-Nov-2014 1 1Best 1 1 Seller2 2 113-Nov-2014 5 Best1 1 2 Seller 1 1 112- 1 1 2Nov-2014Best 1 2 Seller1 1 211-Nov-2014 Best1 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best110-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 2 Best1 9-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 18-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 3 2Best 17-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 6-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-2014 1 Seller1 1 1 1Best 1 5-Nov-20141 Seller1 1 2 1 Best1 4-Nov-20141 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 14-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best1 13-Nov-2014 1 Seller 1 1 1 1 13-Nov-2014Best 1 1 Seller1 1 1 Best12-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best2 2-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 3 1 1 Best1 1-Nov-2014 1 1 Seller 1 1 1 Best5 1-Nov-20141 2 Seller 1 1 1 Best 1 31-Oct-20141 1Seller 1 2 1 Best 1 1 31-Oct-2014 1Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 31-Oct-2014Seller 1 1 1 Best1 1 1 Seller 131-Oct-2014 1 1 Best 1 1 1Seller 1 30-Oct-20141 1 Best 1 3 1Seller 1 1 30-Oct-2014 1 Best1 -

Knight Letter No. 85

^ ^ KNIGHT LETTER ^ ^^ ^ The Lewis Carroll Society ofNorth America Winter 2010 Volume II Issue 15 Number 85 Knight Letter is the official magazine of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America. It is published twice a year and is distributed free to all members. Editorial correspondence should be sent to the Editor in Chief at [email protected]. SUBMISSIONS Submissions for The Rectory Umbrella and Mischmasch should be sent to [email protected]. Submissions and suggestions for Serendipity and Sic Sic Sic should be sent to [email protected]. Submissions and suggestions for From OurFar-Flung Correspondents should be sent to [email protected]. © 2010 The Lewis Carroll Society of North America ISSN 0193-886X Sarah Adams-Kiddy, Editor in Chief Mahendra Singh, Editor, The Rectory Umbrella Sarah Adams-Kiddy ^ Ray Kiddy, Editors, Mischmasch James Welsch 6^ Rachel Eley, Editors, From Our Far-Rung Correspondents Mark Burstein, Production Editor Andrew H. Ogus, Designer THE LEWIS CARROLL SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA President: Mark Burstein, [email protected] Vice-President: Cindy Watte r, [email protected] Secretary: Clare Imholtz, [email protected] www.LewisCarroll . org Annual membership dues are U.S. $35 (regular), $50 (international), and $100 (sustaining). Subscriptions, correspondence, and inquiries should be addressed to: Clare Imholtz, LCSNA Secretary 11935 Beltsville Dr. Beltsville, Maryland 20705 Additional Contributors to This Issue Barbara Adams, Ruth Berman, Angelica Carpenter, Bonnie Hagerman, Alan Tannenbaum, Cindy Watter On the cover: Secret Garden, digital collage by Adriana Peliano. Seepage 21. 1 -^ -^0^ ^ CONTENTS H^ i^y„s^ ^S ^i^"^^^ ^ THe ReCTORY UMBRSLLA OF BOOKS AND THINGS m Livefrom Lincoln Center Evermore Everson 's Everytype! 45 MARK BURSTEIN MARK BURSTEIN Keith Shepard's Wonderland Revisited, Meeting Mr. -

Alice in Wonderland Glossary of Terms for Madge Miller’S Adaptation from Lewis Carroll

Alice in Wonderland Glossary of Terms for Madge Miller’s adaptation from Lewis Carroll Lewis Carroll’s novella Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, on which Madge Miller’s play is based, begins not with Alice sitting on the grass with her sister, but with the following poem, which recalls the “golden afternoon” when Carroll first began telling the story of Alice’s adventures underground to the three Liddell sisters, Lorina (aged 13), Alice (aged 10), and Edith (aged 8). The date was Friday, July 4th, 1862. W.H. Auden once declared that July 4th, 1862 was “as memorable a day in the history of literature as it is in American history.”1 This quote and, indeed, much of the information in this glossary is culled from The Annotated Alice, a volume of Carroll’s work superbly annotated by Martin Gardner, from which I will be citing frequently. The poem which begins Alice’s Adventures reads as follows: All in the golden afternoon Full leisurely we glide; For both our oars, with little skill, By little arms are plied, While little hands make vain pretence Our wanderings to guide. Ah, cruel Three! In such an hour, Beneath such dreamy weather, To beg a tale of breath too weak To stir the tiniest feather! Yet what can one poor voice avail Against three tongues together? Imperious Prima flashes forth Her edict to “begin it”: In gentler tones Secunda hopes “There will be nonsense in it!” While Tertia interrupts the tale Not more than once a minute. Anon, to sudden silence won, In fancy they pursue The dream-child moving through a land Of wonders wild and new, In friendly chat with bird or beast— And half believe it true. -

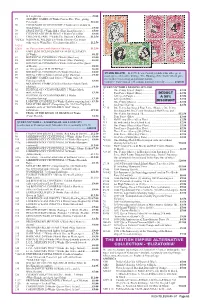

The British Empire Alternative Collection

in 5 segments ..........................................................................POR 77 OLYMPIC GAMES 20 Winks Caucus Race Prize-giving Ceremony .............................................................................£10.00 78 CENTENARY OF DISCOVERY 5 Winks Alice at door to Wonderland ............................................................................£5.00 79 SPACE ISSUE 3 Winks Bill 1 (First Lizard in space) ...........£5.00 80 CITIZENS ADVISE BUREAU 4 Winks Caterpillar .............£8.00 81 CHILD WELFARE 9 Winks The Duchess’s Kitchen .........£12.50 *82/82a NATIONAL WILDLIFE 8 Winks Cheshire Cat in pair with variety Worn Plate (Cat almost invisible) ....................£12.50 *82(i)/ 82a(i) do. Pair as above with Sanserif lettering .............................£12.50 83 UMPTEENTH CENTENARY OF MAD TEA PARTY 20 Winks .................................................................................£6.25 84 BOTANICAL CONGRESS 3 Winks (Gardener) ..................£5.00 85 BOTANICAL CONGRESS 4 Winks (Rose Painting) ...........£6.00 86 BOTANICAL CONGRESS 6 Winks (Arrival of the Queen of Hearts) ................................................................................£6.00 87 do. Overprinted “R.H. OFFICIAL” .......................................£6.00 88 BOTANICAL CONGRESS 2½ Winks (Gardener) ...............£4.00 SNARK ISLAND – In 1876, Lewis Carroll published his other great 89 ROYAL VISIT 6 Winks (Arrival of the Duchess) .................£9.50 masterpiece of creative writing, ‘The Hunting of the Snark’ which gave -

Jabberwocky Notes

Jabberwocky Notes The Jabberwock: John Tenniel (Illustrator) “It seems very pretty,' she said when she had finished it, 'but it's rather hard to understand!' (You see she didn't like to confess, even to herself, that she couldn't make it out at all.) 'Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas—only I don't exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something: that's clear, at any rate” Alice’s comments after reading the poem, “Jaberwocky” Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll According to scholars and critics, the original purpose of "Jabberwocky" was to satirize or make fun of pretentious verse and ignorant literary critics. It was designed to be a poem showing how not to write poetry that is too difficult for others to understand. Many, however, misunderstood this. It is often now cited as one of the greatest nonsense poems written in the English language. Many of the words he created have become neologisms. Neologism: (from the Greek root meaning “new” and “speech”) Words that appear in literature that are used so often by the general public that they become accepted new words. Possible interpretations of words: Bandersnatch: A swift moving creature with snapping jaws, capable of extending its neck. A 'bander' was also an archaic word for a 'leader', suggesting that a 'bandersnatch' might be an animal that hunts the leader of a group. Beamish: Radiantly beaming, happy, cheerful. Although Carroll may have believed he had coined this word, it is cited in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1530. -

Lewis Carroll

Alice in Wonderland (Poetry in Motion) Study Guide A Ballet Presented by State Street Ballet of Santa Barbara Sponsored by the Valley Performing Arts Council Janet M. Kelly [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 3 Letter to Educators 4-6 Biographical Information about Lewis Carroll 7 The “Real” Alice in Wonderland, Alice Liddel 8-10 Summary of the story “Alice in Wonderland” 11-12 State Street Ballet of Santa Barbara Ballet Information 13-14 “Jabberwocky” Poem and Activities 15-16 Characters in Alice in Wonderland Critical thinking about the symbolism of the characters 17-18 Poetry in Motion 19-20 “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane, Woodstock, 1969 A critical thinking exercise for older students 21 Bibliography 2 Dear Educators, State Street Ballet of Santa Barbara’s version of Alice in Wonderland is one of the most student friendly ballets I’ve witnessed. It is appropriate for very young students who will take the story literally. It is also appropriate for older students who may want to delve into the historical context, innuendo, and figurative nature of Alice in Wonderland. The costumes and choreography tell a wordless story so well that students who have never seen ballet will comprehend what the dancers are trying to convey. I’ve titled this Study Guide as “Poetry in Motion” because I found that movement can tell a story, or help interpret a poem, so the meaning of the writing is understandable for even the youngest student. This study guide has background information, and a variety of points-of-view that can appeal to young students as well as adults. -

To Catch a Bandersnatch1

©1970, 2004 Mark Burstein To Catch a Bandersnatch1 ©1970, 2004 Mark Burstein There is a possession and a madness inspired by the Muses, which seizes upon a tender virgin soul, and, stirring it up to rapturous frenzy, adorns, in ode and other verse, the countless deeds of elder time for the instruction of after ages. But whosoever without the madness of the Muses comes to knock at the doors of poesy, from the conceit that haply by forced art he will become an efficient poet, departs with blasted hopes, and his poetry, the poetry of sense, fades into obscurity before the poetry of madness. Plato, Phaedrus I. Prelude: Alice in Hermeneutica In a story called “The Book of Sand”, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges tells a story about a meeting between a dealer in rare books and an itinerant Bible salesman, who sells him a very old and worn volume of Holy Writ in an Arabic script. The peddler called it “The Book of Sand” because like the sands it was without beginning and without end and contained an infinite number of pages. One simply could never turn to the first page or the last and of those pages in the middle, no page which had once been seen could, after turning, ever be found again. While Borges intended this as an allegory for all books, or perhaps more broadly, for the limitlessness of our search for knowledge, I often feel he may have been specifically referring to the Alice books2 of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, pseud. Lewis Carroll. It is doubtful if any two people have ever read quite the same version of these - I certainly never have.