Patrick Leary Shirley Brooks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pecuniary Explication of William Makepeace Thackeray's Critical Journalism

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 "Show Me the Money!": A Pecuniary Explication of William Makepeace Thackeray's Critical Journalism Gary Simons University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Simons, Gary, ""Show Me the Money!": A Pecuniary Explication of William Makepeace Thackeray's Critical Journalism" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3347 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Show Me the Money!”: A Pecuniary Explication of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Critical Journalism by Gary Simons A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Pat Rogers, Ph.D., Litt. D. Marty Gould, Ph.D. Regina Hewitt, Ph.D. Laura Runge, Ph.D. Date of Approval March 24, 2011 Keywords: W. M. Thackeray, British Literature, Literary Criticism, Periodicals, Art Criticism Copyright © 2011, Gary Simons Dedication To my wife Jeannie, my love, my companion and partner in life and in learning, who encouraged me to take early retirement and enter graduate school, shared with me the pleasures of the study of English literature and thereby intensified them, patiently listened to my enthusiasms, and urged me onward at every stage of this work, Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. -

Dickens Brochure

Message from John ne of the many benefits that came to us as students at the University of Oklahoma and Mary Nichols during the 1930s was a lasting appreciation for the library. It was a wonderful place, not as large then as now, but the library was still the most impressive building on campus. Its rich wood paneling, cathedral-like reading room, its stillness, and what seemed like acres of books left an impression on even the most impervious undergraduates. Little did we suspect that one day we would come to appreciate this great OOklahoma resource even more. Even as students we sensed that the University Library was a focal point on campus. We quickly learned that the study and research that went on inside was important and critical to the success of both faculty and students. After graduation, reading and enjoyment of books, especially great literature, continued to be important to us and became one of our lifelong pastimes. We have benefited greatly from our past association with the University of Oklahoma Libraries and it is now our sincere hope that we might share our enjoyment of books with others. It gives us great pleasure to make this collection of Charles Dickens’ works available at the University of Oklahoma Libraries. “Even as As alumni of this great university, we also take pride in the knowledge that the library remains at the students center of campus activity. It is gratifying to know that in this electronic age, university faculty and students still we sensed that find the library a useful place for study and recreation. -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 2015 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. Subscription rates per volume for 2015 (includes shipping): U.S. $65.00; international $75.00. Send orders for subscriptions and back issues to the Institute. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site, with the current issue added when that volume is completed. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information. -

The Aspiring Men of Punch: Patrolling the Boundaries of the Victorian Gentleman a Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate S

The Aspiring Men of Punch: Patrolling the boundaries of the Victorian gentleman A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Marc Usunier © Copyright Marc Usunier, April 2010. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Arts degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT In the mid 1830s, the engraver Ebenezer Landells and the journalist Henry Mayhew began discussions about establishing a satirical news magazine together. -

Grindlay Or the Bank

GRINDLAYS BANK The following is extracted from the book: ‘100 Years of Banking in Asia and Africa, 1863 – 1963’ by Geoffrey Tyson: Chapter XV. Forming New Alliances.. Published in London in 1963. Prints of Indian scenes are by Grindlay. ROBERT MELVILLE GRINDLAY (1786-1877) was that peculiarly English product, the gifted amateur. He was born at St. Mary-le-Bone, then a village near London and, to put the event into historical perspective, it occurred two years after the passing of Pitt's India Act and two years before Warren Hastings' impeachment and trial began. The years of Grindlay's youth were thus a time when Indian affairs loomed large in English life, and at the age of 17 he secured a nomination as a cadet in the East India Company's Army, arriving in Bombay in 1803. A year later he was promoted to lieutenant, and by 1817 he had reached the exalted rank of captain which remained the high water mark of his military career. At the end of 1820 he retired on half-pay, which for his rank amounted to five shillings a day at that period. By this time he was 34 years old and it might have seemed that, with his relegation to a half-pay officer on the strength of the 2nd battalion of the 7th Bombay Native Infantry, his working days were over. Such were the conditions in which upper middle-class young Englishmen of the period might expect their careers to be moulded. At this stage a foreshortened and undistinguished record as a soldier and some talent as an artist were pretty well all Grindlay had to offer to the world of business or administration. -

Catalog of the Peal Exhibition: Victorians I John Spalding Gatton University of Kentucky

The Kentucky Review Volume 4 Number 1 This issue is devoted to a catalog of an Article 12 exhibition from the W. Hugh Peal Collection in the University of Kentucky Libraries. 1982 Catalog of the Peal Exhibition: Victorians I John Spalding Gatton University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Gatton, John Spalding (1982) "Catalog of the Peal Exhibition: Victorians I," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol4/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. :l Victorians I :o her an f the !ds do 127. Engraved portrait of Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1852. From the collection of HenryS. Borneman. Peal 9,572. 128. THOMAS BABINGTON MACAULAY. A.L.s. to unnamed correspondent, 16 September 1842. Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859) showed great precocity, at the age of eight planning a Compendium of Universal History. In his youth he also composed three cantos of The Battle of Chevoit, an epic poem in the manner of Scott's metrical romances; a lengthy poem on Olaus Magnus; and a piece in blank verse on Fingal. At Trinity College, Cambridge, he twice won the Chancellor's Medal for English Verse, and became a Fellow of Trinity. -

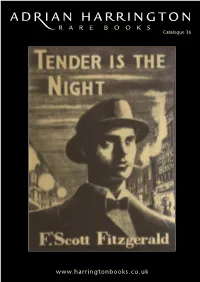

Harringtons Cat 36 Complete Layout 1

Catalogue 36 www.harringtonbooks.co.uk This catalogue contains highlights from our extensive stock. Besides library sets, we also specialise in rare and modern first editions including children’s illustrated books. Churchilliana, crime and detective fiction, travel and voyages.Please contact us if you have any queries, we'll be happy to help. Cover Image: Fitzgerald; Tender is The Night. 64a Kensington Church Street, Kensington London W8 4DB tel +44 (0) 20 7937 1465 fax +44 (0) 20 7368 0912 email: [email protected] Welcome to Adrian Harrington Rare Books Catalogue No. 36. Please feel free to contact us regarding any queries or requests. 1 (ALDIN, Cecil) SEWELL, Anna. Black Beauty. The Autobiography of a Horse. London: Jarrolds Publishers Limited, [37987 ] First Cecil Aldin illustrated Edition. Publisher's green cloth with titles in gilt to spine, gilt pictorial title to upper, top edges tinted green. In its original white pictorial dust jacket titled in blue. Illustrated with 18 full page coloured plates. The book is tight, content fine, gilt bright; dust jacket a little dusty, frayed along extremities with closed tears reinforced by tape on the insides, top of back panel with 1 x 2 inches loss. A superb copy of this classic story; uncommon in its original dust jacket. £375 2 ALISON, Archibald. History of Europe, from the commencement of the French Revolution to the Restoration of the Bourbons in 1815. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1849. [38168 ] 14 volumes; 8vo. (22 x 65 cm). Contemporary full brown diced calf, black and tan title labels, gilt raised bands to blind tooled spines, marbled end papers and edges. -

Inventing Poetry and Pictorialism in Once a Week: a Magazine of Visual Effects

Inventing Poetry and Pictorialism in Once a Week: A Magazine of Visual Effects LINDA K. HUGHES n unusually direct terms the illustrated weekly magazine that debuted on July I2, 1859, generally deemed a high point of mid-century illustration,1 resulted from male desire. Working with Ellen Ternan on The Frozen Deep aroused Charles Dickens’ passions and his determination to separate formally from his wife Catherine.2 When Dickens announced the separation in the June 12, 1858 issue of Household Words, the magazine he had run in a partnership with the firm Bradbury and Evans since 1850, he expected Punch, another Bradbury and Evans publication, to reprint the announcement. It did not. Furious, Dickens took immediate steps to end his business relationship with the firm and found a rival publication of which he would be editor and prin- cipal proprietor. Thus was All the Year Round born on April 30, 1859.3 Rather than simply letting Dickens exit and take Household Words staff with him, William Bradbury and Frederick Evans determined to start a rival magazine. Though it, too, would be a weekly literary magazine, it would mark its bold departure from Dickens’ magazine by being illustrated and employing some of the best artists and engravers available. Yet Once a Week would be priced at only three pennies an issue (compared to Dickens’ two). This odd intersection of Dickensian desire and print culture is also an important node in the history of Victorian illustrated poetry. Once a Week appeared at a crucial pivot in the publishing history of poetry and periodicals. -

Dickens and the Middle-Class Weekly John Drew Between 30 March 1850

Dickens and the middle-class weekly John Drew Between 30 March 1850 and his death on 9 June 1870, Dickens was the editor and part- owner, latterly also the publisher (1859-1870), of two of the most prominent periodicals in the Anglophone world, Household Words and All the Year Round. Here were serialised many of the nineteenth-century’s most notable works of fiction—among them Hard Times, North and South, Cranford, A Tale of Two Cities, The Woman in White, Great Expectations and The Moonstone—together with well over 7,000 original short stories, poems, non-fiction articles, essays, reports and exposés, the majority of them commissioned, cajoled and copy-edited (at times, entirely re-written) by Dickens and his trusty sub-editor, W. H. Wills. To Lord Northcliffe of the Daily Mail Dickens was, quite simply, ‘the greatest magazine editor either 1 of his own, or any other age.’ For the American intellectual and Harper’s Weekly editor Commented [EJS1]: Endnotes rather than footnotes please George W. Curtis, toasting Dickens’s health in front of 200 other newspapermen in 1868, Commented [.2]: Done there was ‘no doubt that among the most vigorous forces in the elevation of the character of the Weekly Press ha[ve] been Household Words and All the Year Round; and since the beginning of the publication of Household Words, the periodical literature of England has been born again.’2 The founding of Household Words was itself the consummation of a desire to sit in the driver’s cab (as Dickens liked to see it3) of a periodically-issued publication that he had harboured since his first steps in journalism, but which found expression in a variety of abortive projects in the late 1830s and early 1840s. -

Charles Dickens

N°. III. IVTIoCe6afe, an3 for Expoz tatioti. CHARLES DICKENS. curs7 LONDON: BRADBURY & EVANS, WHITEFRIARS. AGENTS :-J. MENZIES, EDINBURGH ; J. MACLEOD, GLASGOW ; J. 1\ IGLASHAN, DUBLIN. NNW FEATHER BEDS PURIFIED BY STEAM. HEAL AND SON Have just completed the erection of Machinery for the purifying of Feathers on a new principle, by which the offensive properties of the quill are evaporated and carried off in steam ; thereby not only are the impurities of the feather itself removed, but they are rendered quite free from the unpleasant smell of the stove, which all new feathers are subject to that are dressed in the ordinary way. Old Beds re-dressed by this process are perfectly freed from all impurities, and, by expanding the feathers, the bulk is greatly increased, and consequently the bed rendered much softer, at 3d. per lb The following are the present prices of new Feathers : Per lb. Per lb. s.d. s. d. Mixed . 1 0 Best Foreign Grey Goose . , 2 0 Grey Goose . 1 4 Best Irish White Goose . 2 6 Foreign Grey Geese . 1 8 Best Dantzie White Goose . 3 0 REAL AND SON'S LIST OF BEIER% Sent free, by Post. It contains full particulars of WEIGHTS, SIZES, and PRICES, of every description of Bedding, and is so arranged that purchasers are enabled to judge the articles best suited to make a comfortable Bed, either as regular English Bedding with a Feather Bed, or as French Bedding with their SUPERIOR FRENCH MATTRESSES, of which they, having been the Original Introducers, are enabled to make them of the very finest material, (quite equal to the best made in Paris,) at a lower price than any other House. -

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens Authors and Artists for Young Adults, 1998 Updated: April 27, 2004 Born: February 07, 1812 in Portsmouth, United Kingdom Died: June 09, 1870 in Gad's Hill, United Kingdom Other Names: Dickens, Charles John Huffam; Boz Nationality: British Occupation: Novelist Novelist, journalist, court reporter, editor, amateur actor. Editor of London Daily News, 1846; founder and editor of Household Words, 1833-35, and of All the Year Round, 1859-70; presented public readings of his works, beginning 1858. He was only fifty-eight when he died. His horse had been shot, as he had wanted; his body lay in a casket in his home at Gad's Hill, festooned with scarlet geraniums. Tributes poured in from all over his native England and from around the world. Statesmen, commoners, and fellow writers all grieved his passing. As quoted in Peter Ackroyd's monumental study, Dickens, the news of Charles Dickens death on June 9, 1870, reverberated across the Atlantic, eliciting the poet Longfellow to say that he had never known "an author's death to cause such general mourning." England's Thomas Carlyle wrote: "It is an event world-wide, a unique of talents suddenly extinct." And the day after his death, the newspaper Dickens once edited, the London Daily News, reported that Dickens had been "emphatically the novelist of his age. In his pictures of contemporary life posterity will read, more clearly than in contemporary records, the character of nineteenth century life." It was a judgment that has been proven more than perceptive. Not only was Dickens a popular recorder of the life of his times, but he was also an incredibly successful man of letters. -

Guide to the Charles Dickens Collection, 1837 •Fi 1981 (Bulk

Bridgewater State University Maxwell Library Archives & Special Collections Charles Dickens Collection, 1837 – 1981, (Bulk 1837 – 1904) (MSS-021) Finding Aid Compiled by Orson Kingsley Last Updated: January 13, 2020 Maxwell Library Bridgewater State University 10 Shaw Road / Bridgewater MA 02325 / 508-531-1389 Finding Aid: Charles Dickens Collection 2 Volume: 1 linear foot (3 document boxes) Acquisition: All items in this manuscript group were donated to or purchased by Bridgewater State University. Access: Access to this record group is unrestricted. Copyright: The researcher assumes full responsibility for conforming with the laws of copyright. Whenever possible, the Maxwell Library will provide information about copyright owners and other restrictions, but the legal determination ultimately rests with the researcher. Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be discussed with the University Archivist. Charles Dickens Biographical Sketch Charles Dickens, born February 7, 1812, was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world’s most well-known fictional characters and is generally regarded as one of, if not the greatest, novelist of the Victorian Period. His work was, and continues to be, highly popular. Many aspects of his stories and his characters have become embedded in our culture and continue to influence society to this day. He died on June 9, 1870. Scope and Content Note The Maxwell Library holds two separate Charles Dickens Collections. One collection pertains solely to books and pamphlets by, about, or relating to Charles Dickens and the London of his era that influenced his work. This collection consists of over 700 individual items, including a majority of first editions of his novels in both serial and book form (a list is included below).