Introduction.Pdf (3.516Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles' Childhood

Charles’ Childhood His Childhood Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812 in Portsmouth. His parents were John and Elizabeth Dickens. Charles was the second of their eight children . John was a clerk in a payroll office of the navy. He and Elizabeth were an outgoing, social couple. They loved parties, dinners and family functions. In fact, Elizabeth attended a ball on the night that she gave birth to Charles. Mary Weller was an early influence on Charles. She was hired to care for the Dickens children. Her bedtime stories, stories she swore were quite true, featured people like Captain Murder who would make pies of out his wives. Young Charles Dickens Finances were a constant concern for the family. The costs of entertaining along with the expenses of having a large family were too much for John's salary. In fact, when Charles was just four months old the family moved to a smaller home to cut expenses. At a very young age, despite his family's financial situation, Charles dreamed of becoming a gentleman. However when he was 12 it looked like his dreams would never come true. John Dickens was arrested and sent to jail for failure to pay a debt. Also, Charles was sent to work in a shoe-polish factory. (While employed there he met Bob Fagin. Charles later used the name in Oliver Twist.) Charles was deeply marked by these experiences. He rarely spoke of this time of his life. Luckily the situation improved within a year. Charles was released from his duties at the factory and his father was released from jail. -

Financial Statements 31 July 2012

Financial Statements 31 July 2012 The Conservatoire for Dance and Drama Tavistock House Tavistock Square London WC1H 9JJ Company number: 4170092 Charity number: 1095623 2 Contents Company Information 5 Report of the Board of Governors 6 Conservatoire Student Public Performances 2011-12 17 Statement of Responsibilities of the Board Of Governors 22 Corporate Governance Statement 23 Independent Auditors’ Report to the Members of the Conservatoire for Dance and Drama 27 Income and Expenditure Account 29 Balance Sheet 30 Cash Flow Statement 31 Statement of Principal Accounting Policies 32 Notes to the Financial Statements 33 Copies of these financial statements can be obtained from the registered office overleaf and are available in large print and other formats on request. 3 4 Company Information Governors James Smith CBE (Chairman) Nicholas Karelis (These are all company directors, Prof Christopher Bannerman Sir Tim Lankester charity trustees and members of Rosemary Boot Susannah Marsden the company.) Kim Brandstrup Richard Maxwell Ralph Bernard Alison Morris Kit Brown Simon O’Shea Richard Cooper Luke Rittner Christopher de Pury Anthony Smith Ryan Densham Andrew Summers CMG Emily Fletcher Kathleen Tattersall OBE Melanie Johnson Joint Principal Prof Veronica Lewis MBE Edward Kemp (also Governors and Directors) (Accountable Officer) Clerk to the Board of Governors and John Myerscough/Claire Jones (from Nov 27 2012) Company Secretary Registered Address Tavistock House Tavistock Square London, WC1H 9JJ Affiliates founding London Contemporary -

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

Catalogue of the Original Manuscripts, by Charles Dickens and Wilkie

UC-NRLF B 3 55D 151 1: '-» n ]y>$i^

Dicken's Tattycoram and George Eliot's Caterina Sarti Beryl Gray

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2001 Nobody's Daughters: Dicken's Tattycoram and George Eliot's Caterina Sarti Beryl Gray Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Gray, Beryl, "Nobody's Daughters: Dicken's Tattycoram and George Eliot's Caterina Sarti" (2001). The George Eliot Review. 411. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/411 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NOBODY'S DAUGHTERS: DICKENS'S TATTY CORAM AND GEORGE ELIOT'S CATERINA SARTI1 by Beryl Gray Doughty Street, where Dickens lived for three years (1836-9), is within a stone's throw of the site of London's Hospital for Foundling Children, which was established in 1739 by the retired sea-captain, Thomas Coram, whom Dickens venerated. Tavistock House - Dickens's home 1851-60, and where he wrote Little Dorrit, the novel in which Tattycoram appears - was also only a short walk from the Hospital. Dickens entirely approved of the way the 'Foundling' was managed in his own day. The Household Words article 'Received, a Blank Child',' which he co-authored with his sub-edi tor, W. H. Wills, unreservedly praises the establishment's system of rearing, training, and apprenticing its charges. -

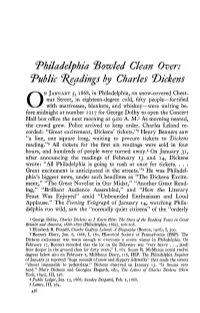

Readings by Charles 'Dickens

Philadelphia ^Bowled Clean Over: Public "Readings by Charles 'Dickens N JANUARY 5, 1868, in Philadelphia, on snow-covered Chest- nut Street, in eighteen-degree cold, fifty people—fortified O with mattresses, blankets, and whiskey—were waiting be- fore midnight at number 1217 for George Dolby to open the Concert Hall box office the next morning at 9:00 A. M.1 As morning neared, the crowd grew. Police arrived to keep order. Charles Leland re- corded: "Great excitement, Dickens' tickets."2 Henry Benners saw "a line, one square long, waiting to procure tickets to T)ickens reading."3 All tickets for the first six readings were sold in four hours, and hundreds of people were turned away.4 On January 31, after announcing the readings of February 13 and 14, Dickens wrote: "All Philadelphia is going to rush at once for tickets. Great excitement is anticipated in the streets."5 He was Philadel- phia's biggest news, under such headlines as "The Dickens Excite- ment," "The Great Novelist in Our Midst," "Another Great Read- Ing," "Brilliant Audience Assembled," and "How the Literary Feast Was Enjoyed" amid "Unbounded Enthusiasm and Loud Applause." The Evening "Telegraph of January 14, watching Phila- delphia run wild, saw the "normally quiet citizens" of the "orderly 1 George Dolby, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him: The Story of the Reading Tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 (Philadelphia, 1885), 206-208. 2 Elizabeth R. Pennell, Charles Godfrey Leland: A Biography (Boston, 1906), I, 300. 3 Benners Diary, Jan. 6, 1868, I, 180, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP). -

Dickens : a Chronology of His Whereabouts

Tracking Charles Dickens : A Chronology of his Whereabouts Previous Dickens chronologies have focused on his life and works : this one does not attempt to repeat their work, but to supplement them by recording where he was at any given date. Dickens did not leave a set of appointment diaries, but fortunately he did leave a lifetime of letters, pinpointing at the head both the date and place of composition. This chronology is based on that information as published in the awesome Pilgrim Edition of his letters published by the Oxford University Press. The source of each entry in the chronology is identified. There are more than 14,000 letters in Pilgrim, giving a wealth of detail for the chronology. Many of the letters, of course, were written from his home or office, but he was an indefatigable traveller, and in the evening he still somehow found the energy to write one from his hotel room. Even so, there are inevitably many dates with no letter, and some of those gaps have been (and will be) filled from information in the letters themselves, and from other reliable sources. Philip Currah. DICKENSDAYS E.B. Elias Bredsdorff, Hans Andersen and Charles Dickens : A Friendship and Its Dissolution.Cambridge, Eng. : Heffer, 1956. 140 p. ill. E.P. Edward F. Payne, Dickens Days in Boston : A Record of Daily Events. Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 1927. 274 p. ill. E.J. Edgar Johnson, Charles Dickens : His Tragedy and Triumph. London : Victor Gollancz, 1953. 2 v. (xxii, 1159, cxcvii p.) ill. J.F. John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Trollope, Orley Farm, and Dickens' marriage break-down Citation for published version: O'Gorman, F 2018, 'Trollope, Orley Farm, and Dickens' marriage break-down', English Studies, pp. 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2018.1492228 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/0013838X.2018.1492228 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: English Studies Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in English Studies on 21/9/2018, available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0013838X.2018.1492228. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 1 Trollope, Orley Farm, and Dickens’ Marriage Break-down Francis O’Gorman ABSTRACT Anthony Trollope’s Orley Farm (1861-2), the plot of which the novelist thought the best he had ever conceived, is peculiarly aware of Charles Dickens, the seemingly unsurpassable celebrity of English letters in the 1850s. This essay firstly examines narrative features of Orley Farm that indicate Dickens was on Trollope’s mind—and then asks why. -

“The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens

44 DICKENS QUARTERLY “The Other Woman” – Eliza Davis and Charles Dickens MURRAY# BAUMGARTEN University of California, Santa Cruz he letters Eliza Davis wrote to Charles Dickens, from 22 June 1863 to 8 February 1867, and after his death to his daughter Mamie on 4 August 1870, reveal the increasing self-confidence of English Jews.1 TIn their careful and accurate comments on the power of Dickens’s work in shaping English culture and popular opinion, and their pointed discussion of the ways in which Fagin reinforces antisemitic English and European Jewish stereotypes, they indicate the concern, as Eliza Davis phrases it, of “a scattered nation” to participate fully in the life of “the land in which we have pitched our tents.2” It is worth noting that by 1858 the fits and starts of Jewish Emancipation in England had led, finally, to the seating of Lionel Rothschild in the House of Commons. After being elected for the fifth time from Westminster he was not required, due to a compromise devised by the Earl of Lucan and Benjamin Disraeli, to take the oath on the New Testament as a Christian.3 1 Research for this paper could not have been completed without the able and sustained help of Frank Gravier, Reference Librarian at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Assistant Librarian Laura McClanathan, Lee David Jaffe, Emeritus Librarian, and the detective work of David Paroissien, editor of Dickens Quarterly. I also want to thank Ainsley Henriques, archivist of the Kingston Jewish Community of Jamaica, Dana Evan Kaplan, the rabbi of the Kingston Jewish community, for their help, and the actress Miryam Margolyes for leading the way into genealogical inquiries. -

The Story of Jesus Told by Charles Dickens Kindle

THE LIFE OF OUR LORD: THE STORY OF JESUS TOLD BY CHARLES DICKENS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles Dickens | 144 pages | 08 May 2014 | Third Millennium Press Ltd. | 9781861189608 | English | Wiltshire, United Kingdom The Life of Our Lord: The Story of Jesus Told by Charles Dickens PDF Book First, it does not feel like a Dickens book. TMP, Hardcover. Included in the book are illustrations by Mormon artist Simon Dewey. Never forget this, when you are grown up. Jan 07, Lyn rated it it was amazing Shelves: children , young-adult. Stock Image. Reverend Frederick Buechner author of On the Road with the Archangel and Listening to Your Life Perhaps the most touching aspect of Charles Dickens's The Life of Our Lord is how in it he sets all his literary powers aside and tells the Gospel story in the simple, artless language of any father telling it to his children. And as he is now in Heaven, where we hope to go, and all meet each other after we are dead, and there be happy always together. On the other hand, Oscar Wilde, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf complained of a lack of psychological depth, loose writing, and a vein of saccharine sentimentalism. Many books are written on the life of our Savior that have impacted me more, but given this was written to his chi Good book. Charles Dickens. The family, many years after his death, decided to publish it, the underlying message being that they wanted the world to see the Charles Dickens they had grown up learning about: as a devoted father and devout Christian. -

Charles Dickens and His Cunning Manager George Dolby Made Millions from a Performance Tour of the United States, 1867-1868

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication 12-17-2014 Making it in America: How Charles Dickens and His Cunning Manager George Dolby Made Millions from a Performance Tour of The United States, 1867-1868 Jillian Martin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Recommended Citation Martin, Jillian, "Making it in America: How Charles Dickens and His Cunning Manager George Dolby Made Millions from a Performance Tour of The United States, 1867-1868." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/112 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAKING IT IN AMERICA: HOW CHARLES DICKENS AND HIS CUNNING MANAGER GEORGE DOLBY MADE MILLIONS FROM A PERFORMANCE TOUR OF THE UNITED STATES, 1867-1868 by JILLIAN MARTIN Under the Direction of Leonard Teel, PhD ABSTRACT Charles Dickens embarked on a profitable journey to the United States in 1867, when he was the most famous writer in the world. He gave seventy-six public readings, in eighteen cities. Dickens and his manager, George Dolby, devised the tour to cash in on his popularity, and Dickens earned the equivalent of more than three million dollars. They created a persona of Dickens beyond the literary luminary he already was, with the help of the impresario, P.T. Barnum. Dickens became the first British celebrity to profit from paid readings in the United States. -

Dickens by Numbers: the Christmas Numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round

Dickens by Numbers: the Christmas Numbers of Household Words and All the Year Round Aine Helen McNicholas PhD University of York English May 2015 Abstract This thesis examines the short fiction that makes up the annual Christmas Numbers of Dickens’s journals, Household Words and All the Year Round. Through close reading and with reference to Dickens’s letters, contemporary reviews, and the work of his contributors, this thesis contends that the Christmas Numbers are one of the most remarkable and overlooked bodies of work of the second half of the nineteenth century. Dickens’s short fictions rarely receive sustained or close attention, despite the continuing commitment by critics to bring the whole range of Dickens’s career into focus, from his sketches and journalism, to his late public readings. Through readings of selected texts, this thesis will show that Dickens’s Christmas Number stories are particularly powerful and experimental examples of some of the deepest and most recurrent concerns of his work. They include, for example, three of his four uses of a child narrator and one of his few female narrators, and are concerned with childhood, memory, and the socially marginal figures and distinctive voices that are so characteristic of his longer work. But, crucially, they also go further than his longer work to thematise the very questions raised by their production, including anonymity, authorship, collaboration, and annual return. This thesis takes Dickens’s works as its primary focus, but it will also draw throughout on the work of his contributors, which appeared alongside Dickens’s stories in these Christmas issues.