Land Use and Human Impact in the Dinaric Karst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans ᇺᇺᇺ

when ethnicity did not matter in the balkans when ethnicity did not matter in the balkans ᇺᇺᇺ A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods john v. a. fine, jr. the university of michigan press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2006 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2009 2008 2007 2006 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fine, John V. A. (John Van Antwerp), 1939– When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans : a study of identity in pre-nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the medieval and early-modern periods / John V.A. Fine. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-472-11414-6 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-472-11414-x (cloth : alk. paper) 1. National characteristics, Croatian. 2. Ethnicity—Croatia. 3. Croatia—History—To 1102. 4. Croatia—History—1102–1527. 5. Croatia—History—1527–1918. I. Title. dr1523.5.f56 2005 305.8'0094972–dc22 2005050557 For their love and support for all my endeavors, including this book in your hands, this book is dedicated to my wonderful family: to my wife, Gena, and my two sons, Alexander (Sasha) and Paul. -

Naturist Cruise During Meal Times

These cruises along the Croatian coast and islands promise visits to historic towns and fascinating islands with abundant opportunities for nude sunbathing and swimming. Sail on a charming Croatian coastal ship, while enjoying all the delights the islands dotting the magnificent coastline have to offer. Nudity will be welcome and expected on board except when in port and Naturist Cruise during meal times. On Traditional Ensuite ship With guaranteed departure on June 15, 2019 NORTHERN ROUTE FROM OPATIJA Itinerary: OPATIJA – BAŠKA OR PUNAT (ISLAND KRK) – RAB – OLIB – TELAŠĆICA – MOLAT – MALI LOŠINJ – CRES – OPATIJA Saturday OPATIJA - BAŠKA OR PUNAT (ISLAND KRK) (L) Departure at 13:00h with lunch on board followed by a swimming stop in the crystal clear sea at Bunculuka naturist camp. Continue our route to Krk island - the largest of the Croatian islands. Krk has immense variety in its villages large and small, gentle green promenades bare rocky wilderness, tiny islands and hundreds of hidden bays and beaches. Late afternoon arrival in Baška or Punat (depending on harbour and weather conditions). Time at leisure to enjoy the café-bars and restaurants alongside the waterfront. Overnight in Baška or Punat harbour. Sunday BAŠKA OR PUNAT (ISLAND KRK) - RAB ISLAND (B, L) After breakfast, we cruise towards Rab Island known as the “island of love”. Swimming break at Ciganka (Gypsy) beach - one of the 3 sandy, naturist beaches in Lopar with its unusual shaped sand dunes. Cruise along the Island of Rab enjoying your lunch. Aft ernoon swim at naturist beach Kandarola, one of the oldest naturist beaches in the world, where British king Edward VIII and W allis Simpson took a skinny dip (some historians say that the British royal actually started naturism here). -

St. Stošija Church, Puntamika Zadar – Croatia

ST. STOŠIJA CHURCH, PUNTAMIKA ZADAR – CROATIA Management handbook 03/2020 1 Management plan for church of St. Stošija, Puntamika (Zadar) was compiled by ZADRA NOVA and City of Zadar as part of the activities of the RUINS project, implemented under Interreg Central Europe Programme 2014 – 2020. https://www.zadra.hr/hr/ https://www.grad-zadar.hr/ 2 Content PART 1 – DIAGNOSIS 1. FORMAL DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPERTY …. 7 1.1. Historical analysis of the property …. 7 1.1.1. Historical context of the property – Puntamika area …. 7 1.1.2. History of the church St. Stošija on Puntamika …. 11 1.2. Formal description of the property …. 15 1.2.1. Location …. 15 1.2.2. Short description of the church's premises …. 17 1.2.3. Boundaries …. 19 1.2.4. The purpose of the property and the ownership …. 21 1.3. Conclusions and recommendations …. 22 2. ANALYSIS OF THE VALUE OF THE PROPERTY …. 23 2.1. Analysis of the features crucial for establishing a comparative group …. 23 2.1.1. Location and the surrounding area …. 23 2.1.2. Composition layout of the church's premises and internal historical form of the structure …. 26 2.1.3. Materials, substances and the structure …. 28 2.1.4. Decoration inside the church and the church inventory; original elements being preserved and additional museum exhibits …. 31 2.1.5. Function and property …. 31 2.2. Defining the type of the property and selecting comparative group …. 32 2.3. Valuing criteria and value assessment of the property, based on the reference group …. 34 2.4. -

Procjena Rizika Od Velikih Nesreća Grad Novi Vinodolski

Procjena rizika od velikih nesreća Grad Novi Vinodolski Ožujak, 2018. Procjena rizika od velikih nesreća Grad Novi Vinodolski Naručitelj: Grad Novi Vinodolski PREDMET: Procjena rizika od velikih nesreća Oznaka RN/2017/0137 dokumenta: Izrađivač: DLS d.o.o. Rijeka (Spinčićeva 2, 51 000 Rijeka) Voditelj izrade: Anita Kulušić mag.geol. Suradnici: Josipa Zarić struč. spec. ing. sec Matija Hrastovski mag.ing.geol. Mišo Kucelj mag.ing.geol. Matea Vrljičak mag.ing.aedif. Nikolina Bakšić dipl.ing.geol. Zrinka Valetić dipl.ing.biol. mag.ing.geol. Mišo Kucelj Karlo Fanuko ing.el. Hana Radovanović ing.el. Datum izrade: Ožujak, 2018. M.P. Odgovorna osoba Ovaj dokument u cijelom svom sadržaju predstavlja vlasništvo Grada Novog Vinodolskog te je zabranjeno kopiranje, umnožavanje ili pak objavljivanje u bilo kojem obliku osim zakonski propisanog bez prethodne pismene suglasnosti odgovorne osobe Grada Novog Vinodolskog. Zabranjeno je umnožavanje ovog dokumenta ili njegovog dijela u bilo kojem obliku i na bilo koji način bez prethodne suglasnosti ovlaštene osobe tvrtke DLS d.o.o. Rijeka. 2 od 191 d.o.o. HR-51000 Rijeka, Spinčićeva 2. Tel: +385 51 633 400, Fax: +385 51 633 013 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Procjena rizika od velikih nesreća Grad Novi Vinodolski S A D R Ž A J 1 UVOD .............................................................................................................................. 8 TEMELJ ZA IZRADU PROCJENE RIZIKA .............................................................................. 8 2 OSNOVNE KARAKTERISTIKE PODRUČJA -

Prometna Povezanost

Tourism Introduction Zadar County encompasses marine area from Island Pag to National Park Kornati and land area of Velebit, i.e. the central part of the Croatian coastline. This is the area of true natural beauty, inhabited from the Antique period, rich with cultural heritage, maritime tradition and hospitality. Zadar County is the heart of the Adriatic and the fulfilment of many sailors' dreams with its numerous islands as well as interesting and clean underwater. It can easily be accessed from the sea, by inland transport and airways. Inseparable unity of the past and the present can be seen everywhere. Natural beauties, cultural and historical monuments have been in harmony for centuries, because men lived in harmony with nature. As a World rarity, here, in a relatively small area, within a hundred or so kilometres, one can find beautiful turquoise sea, mountains covered with snow, fertile land, rough karst, ancient cities and secluded Island bays. This is the land of the sun, warm sea, olives, wine, fish, song, picturesque villages with stone- made houses, to summarise - the true Mediterranean. History of Tourism in Zadar Tourism in Zadar has a long tradition. The historical yearbooks record that in June 1879 a group of excursionists from Vienna visited Zadar, in 1892 the City Beautification Society was founded (active until 1918), and in 1899 the Mountaineering and Tourism Society "Liburnia" was founded. At the beginning of the XX century, in March 1902 hotel Bristol was opened to the public (today's hotel Zagreb). Most important period for the development of tourism in Zadar County lasted from the 60's - 80's of the 20th century, when the majority of the hotel complexes were erected. -

Status Report of Vitis Germplasm in CROATIA D. Preiner, E. Maletić University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture. 1. Importance

Status Report of Vitis germplasm in CROATIA D. Preiner, E. Maletić University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture. 1. Importance of the Viticulture in the country Total surface: 18678 ha (2010), Register of grape and wine producers. Total vineyard area: 26111 ha (2010). 2. Collections or germplasm banks for Vitis 1) Faculty of Agriculture Zagreb, experimental station Jazbina: - National collection of native grapevine V. vinifera varieties: 128 Vitis vinifera accessions of native cultivars. - Collection of introduced cultivars and clones: 93 accessions (57 V. vinifera wine cvs. Including 26 clones; 12 interspecific hybrids-wine cvs.; 24 table grape cvs.) 2) Regional (safety) collections: - Institut for Adriatic crops and carst reclamation, Split – Collection of Dalmatia region: 130 accessions of ≈ 90 V. vinifera cultivars. - Collection of native grapevine cultivars of Primorsko-Goranska county – Risika, Island of Krk: 22 native V. vinifera cvs. - Collection of native grapevine cultivars of Hrvatsko zagorje – Donja Pačetina, Krapinsko-Zagorska county: 18 accessions of native V. vinifera cvs. 3. Status of characterization of the collections In all collections characterisation (ampelographic and genetic) is in progress. 4. References of germplasm collections or databases in internet Croatian plant genetic resources database: http://cpgrd.zsr.hr/gb/fruit/ 5. Main varieties in the country In 2010: Graševina B (Welschriesling) (26%) Malvazija istarska (Malvasia Istriana) B (10%) Plavac mali N (9%) Merlot N (4%) Plavina N (3%) Riesling B (3%) Cabernet Sauvignon N (3%) Chardonnay B (3%) Trbljan B (3%) Frankovka N (Blaufränkisch) (2%) Others (less than 2% each): Kujundžuša B N; Babić; Pošip B; Debit B; Moslavac (Furmint) B; Ugni blanc B; Maraština B; Teran N; Pinot blanc B; Kraljevina Rs; Grenache N; Vranac N; Traminer Rg; Sauvignon blanc B; etc. -

Istria & Dalmatia

SPECIAL OFFER - SAVE £200 PER PERSON ISTRIA & DALMATIA A summer voyage discovering the beauty of Istria & Kvarner Bay aboard the Princess Eleganza 28th May to 6th June, 6th to 15th June*, 15th to 24th June, 24th June to 3rd July* 2022 Mali Losinj Brijuni Islands National Park Vineyard in the Momjan region oin us for a nine night exploration of the beautiful Istrian coast combined with a visit to the region’s bucolic interior and some charming islands. Croatia’s Istrian coast and Momjan J Opatija Kvarner Bay offers some of the world’s most beautiful coastal scenery, picturesque islands Porec Motovun Rovinj and a wonderfully tranquil and peaceful atmosphere. The 36-passenger Princess Eleganza CROATIA is the perfect vessel for our journey allowing us to moor centrally in towns and call into Pula secluded bays, enabling us to fully discover all the region has to offer visiting some Brijuni Rab Islands marvellous places which do not cater for the big ships along the way. Each night we will Mali Losinj remain moored in the picturesque harbours affording the opportunity to dine ashore on some evenings and to enjoy the floodlit splendour and lively café society which is so atmospheric. Zadar Our island calls will include Rab with its picturesque Old Town, Losinj Island with its striking bays Dugi Otok which is often to referred to as Croatia’s best-kept secret, Dugi Otok where we visit a traditional fishing village and the islands of the Brijuni which comprise one of Croatia’s National Parks. Whilst in Pula, we will visit one of the best preserved Roman amphitheatres in the world and we will also spend a day travelling into the Istrian interior to explore this area of disarming beauty and visit the village of Motovun, in the middle of truffle territory, where we will sample the local gastronomy and enjoy the best views of the Istrian interior from the ramparts. -

Čavle • Cernik • Mavrinci Gradovi Opcine

godina XII. / br. 40 / rijeka / travanj 2016. / besplatni primjerak magazin primorsko-goranske županije Podno Grobničkih alpa Čavle • Cernik • Mavrinci gradovi opcine OpÊina OpÊina Grad OpÊina OpÊina Viškovo Klana Kastav Jelenje »avle Vozišće 3, 51216 Viškovo Klana 33, 51217 Klana Zakona kastafskega 3, Dražičkih boraca 64, Čavle 206, 51219 Čavle 51215 Kastav T: ++385 51 503 770 T: ++385 51 808 205 51218 Jelenje T: ++385 51 208 310 F: ++385 51 257 521 F: ++385 51 808 708 T: ++385 51 691 452 F: ++385 51 208 311 F:++385 51 691 454 T: ++385 51 208 080 E: nacelnica@opcina- E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] F: ++385 51 208 090 viskovo.hr www.klana.hr www.cavle.hr www.kastav.hr E: [email protected] www.opcina-viskovo.hr Načelnik: www.jelenje.hr Načelnik: Najviše Gradonačelnik: Načelnica: Sanja Udović Matija Laginja Načelnik: Željko Lambaša stanovnika Predsjednik Vijeća: Ivica Lukanović Predsjednik Vijeća: Predsjednica Vijeća: Ervin Radetić Grad Rijeka Slavko Gauš Predsjednik Vijeća: Norbert Mavrinac Jagoda Dabo Predsjednik Vijeća: 128.735 Dalibor Ćiković Nikica Maravić OpÊina Matulji Grad Trg M. Tita 11, Rijeka Površina 51211 Matulji Korzo 16, 51000 Rijeka OpÊina kopna T: ++385 51 209 333 T: ++385 51 274 114 Kostrena 3.588 km2 F: ++385 51 401 469 F: ++385 51 209 520 Sv. Lucija 38, 51221 Kostrena E: [email protected] E: [email protected] T: ++385 51 209 000 www.matulji.hr www.rijeka.hr F: ++385 51 289 400 Načelnik: Gradonačelnik: mr.sc. Vojko Obersnel E: [email protected] Mario Ćiković www.kostrena.hr Predsjednik Vijeća: Predsjednica Vijeća: Slobodan Juračić Dorotea Pešić-Bukovac Načelnica: Dužina Mirela Marunić morske Predsjednica Vijeća: obale Gordana Vukoša 1.065 km Grad OpÊina Opatija Lovran Šetalište M. -

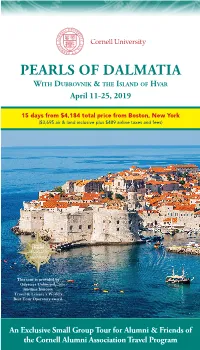

Pearls of Dalmatia with Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar

PEARLS OF DALMATIA WITH DUBROVNIK & THE ISLAND OF HVAR April 11-25, 2019 15 days from $4,184 total price from Boston, New York ($3,695 air & land inclusive plus $489 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumni & Friends of the Cornell Alumni Association Travel Program Dear Alumni, Parents, and Friends, We invite you to be among the thousands of Cornell alumni, parents and friends who view the Cornell Alumni Association (CAA) Travel Program as their first choice for memorable travel adventures. If you’ve traveled with CAA before, you know to expect excellent travel experiences in some of the world’s most interesting places. If our travel offerings are new to you, you’ll want to take a closer look at our upcoming tours. Working closely with some of the world’s most highly-respected travel companies, CAA trips are not only well organized, safe, and a great value, they are filled with remarkable people. This year, as we have for more than forty years, are offering itineraries in the United States and around the globe. Whether you’re ascending a sand dune by camel, strolling the cobbled streets of a ‘medieval town’, hiking a trail on a remote mountain pass, or lounging poolside on one of our luxury cruises, we guarantee ‘an extraordinary journey in great company.’ And that’s the reason so many Cornellians return, year after year, to travel with the Cornell Alumni Association. -

Discovering Dalmatia

PROGRAmme AND BOOK OF AbstRActs DISCOVERING DALMATIA The week of events in research and scholarship Student workshop | Public lecture | Colloquy | International Conference 18th-23rd May 2015 Ethnographic Museum, Severova 1, Split Guide to the DISCOVERING week of events in research and DALMATIA scholarship Student (Un)Mapping Diocletian’s Palace. workshop Research methods in the understanding of the experience and meaning of place Public Painting in Ancona in the 15th century with several lecture parallels with Dalmatian painting Colloquy Zadar: Space, time, architecture. Four new views International DISCOVERING DALMATIA Conference Dalmatia in 18th and 19th century travelogues, pictures and photographs Organized by Institute of Art History – Centre Cvito Fisković Split with the University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy and the Ethnographic Museum in Split 18th-23rd May 2015 Ethnographic Museum, Severova 1, Split (Un)Mapping Diocletian’s Palace. Workshop of students from the University of Split, Faculty Research methods in the of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy - University understanding of the experience study of Architecture and Faculty of Humanities and Social and meaning of place Sciences - Department of Sociology Organisation and Hrvoje Bartulović (Faculty of Civil Engineering, mentoring team Architecture and Geodesy = FGAG), Saša Begović (3LHD, FGAG), Ivo Čović (Politecnico di Milano), Damir Gamulin, di.di., Ivan Jurić (FGAG), Anči Leburić, (Department of Sociology), Iva Raič Stojanović -

Transfers from Kvarner

TRANSFERS FROM KVARNER Special offers not applicable (special offer family package or any other special offer). Transfers are guaranteed until 2pm day before departure- after that time transfers are on request subject to availability. OPATIJA TRANSFERS 05:40 Moscenicka draga Pick up point is at the bus stop in the centre of Moscenicka draga 05:40 Medveja Pick up point is at the bus stop in the centre of Medveja (accrossroad of camp entrance) 05:50 Lovran- centre Pick up point is at the bus stop in the centre of Lovran 05:50 Lovran- hotel Excelsior Pick up point is at the bus stop on the main road in front of hotel Excelsior 05:50 Ika Pick up point is at the bus station in the centre of Ika 05:50 Icici Pick up point is at the bus stop in the centre of Icici 06:00 Opatija- Slatina Pick up point is at the main bus station in Opatija (near petrol station Ina) 06:00 Opatija- Admiral and Kristal Pick up point is at the bus stop on the road near hotel Admiral 06:05 Opatija- food market Pick up point is at the bus stop in front of the food market (opposite Zagrebacka bank) 06:05 Opatija- hotel Belvedere Pick up point is at the bus station above hotel Belvedere KRK TRANSFERS 03:45 Krk, Baska- hotel Corinthia Pick up point is in front of the reception of hotel Corinthia (in front of the barrier) 04:05 Krk, Punat Pick up point is at the bus station in the centre of Punat 04:20 Krk, hotel Drazica Pick up point is in front of hotel Drazica 04:20 Krk, city Krk Pick up point is at the bus station in the centre of city Krk 04:30 Krk- Blue Wave Pick up point is in front of hotel Blue Wave 04:35 Krk, Malinska Pick up point is at the bus station in the centre of Malinska (new bus station) 04:45 Krk, Njivice Pick up point is at the bus stop on the main street above the roundabout of Hotel Jadran 04:55 Resort Uvala Scott- Kraljevica Pick up point is on the main entrance of resort Uvala Scott (crossroad 50 meters distance from the barrier) . -

Charter Info

Personal identification number: 3113 871 8573 Company number: 1746057 Mobile: + 38595 735 6717 + 38598 273 776 + 38595 597 7952 + 38598 418 954 Web: www.sailing-jt.com e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Address: Dr. Jurja Dobrile 32, 10410, Velika Gorica / Croatia Manager: Štefica Toth facebook Jedra Turopolja __________________________________________________________________________________________ CHARTER INFO After arriving at the base, You will be at our service permanently during Your cruising. CHECK IN PROCEDURE MARINA PUNAT Check in - Saturday, from 17:00h Should You arrive earlier than 17.00h, please advice us, so we can inform You if it is possible to do the check in earlier or if You have to wait till 17:00h. At this time the boat will be ready for inspection You will find our inventory list in the boat, to check yourself After making sure that all inventory is complete, list has to be signed Immediately after, one of our staff members will give full technical explanation of all systems and functions on/of the boat Finally, when the security deposit is left, You are free to start your trip NOTE: Skipper's license is mandatory CHECK OUT PROCEDURE MARINA PUNAT Check out - Saturday, from 09:00h At this time the yacht must be clean, all inventory at it's place and the crew with their luggage out of the boat. By checking out, the responsible person is checking the inventory and equipment (together with You or the skipper in charge). If all is found in order, You will have the security deposit reimbursed. Necessary time for this operation is about 30 min.