Review of the Regulatory Powers, Resources and Functions of the JCRA As a Telecommunications Regulator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Trinity Autumn 2015.Pdf

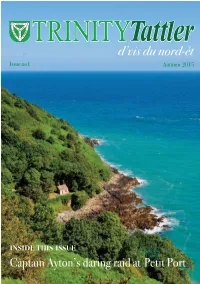

TRINITY.qxp_Layout 1 26/10/2015 15:40 Page 2 d’vis du nord-êt Issue no1 Autumn 2015 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Captain Ayton’s daring raid at Petit Port TRINITY.qxp_Layout 1 26/10/2015 15:40 Page 3 During winter, Les Hoûmets is always warm and cosy with festive treats galore of Gorey Village, Les HoûmetsHo Care Home has been established and operated by the Amy family for over 30 years. A true ‘home from home’, Les Hoûmets Care Les Hoûmets Care Home offers all levels of Home is always warm, welcoming and cosy. residential personal care, from entry level to Our residents are encouraged to invite friends high dependency support. Owned and operated and family to visit at a time convenient for them. by the Amy family, our experienced, fully Meal times are flexible, and there are winter qualified and friendly staff provide 24 hour care. treats galore – from gorgeous casseroles, roasts, With the addition of our four brand-new and homemade soups and desserts, to a traditional luxuriously appointed suites, styled with Laura Christmas roast with all the trimmings, Ashley décor and top of the range bedding and Christmas pudding, cake and mince pies. furnishings, we add further choice to our At Les Hoûmets, we also understand the benefits care solutions. of staying active. We offer a full range of leisure Call Monica Meredith, our friendly Home pursuits throughout the year including singing, Manager, on 855656 to arrange a visit. keep fit, arts & crafts, and theatre trips. T: 855656 | W: leshoumets.com | E: [email protected] TRINITY.qxp_Layout 1 26/10/2015 15:53 Page 4 WELCOME Welcome to the Trinity Tattler! IN THIS edition 4 From the Connétable and Deputy 7 Battle of Flowers success 8 Trinity Church news 16 Commando raid at Petit Port We’re proud to bring to you the first edition of the Trinity 20 Trinity treasures Tattler, a quarterly colour magazine which we hope will appeal to Parishioners of all ages. -

The Story of New Jersey

THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY HAGAMAN THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Examination Copy THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY (1948) A NEW HISTORY OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY is for use in the intermediate grades. A thorough story of the Middle Atlantic States is presented; the context is enriohed with illustrations and maps. THE STORY OF NEW JERSEY begins with early Indian Life and continues to present day with glimpses of future growth. Every aspect from mineral resources to vac-| tioning areas are discussed. 160 pages. Vooabulary for 4-5 Grades. List priceJ $1.28 Net price* $ .96 (Single Copy) (5 or more, f.o.b. i ^y., point of shipment) i^c' *"*. ' THE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING COMPANY Linooln, Nebraska ..T" 3 6047 09044948 8 lererse The Story of New Jersey BY ADALINE P. HAGAMAN Illustrated by MARY ROYT and GEORGE BUCTEL The University Publishing Company LINCOLN NEW YORK DALLAS KANSAS CITY RINGWOOD PUBLIC LIBRARY 145 Skylands Road Ringwood, New Jersey 07456 TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW.JERSEY IN THE EARLY DAYS Before White Men Came ... 5 Indian Furniture and Utensils 19 Indian Tribes in New Jersey 7 Indian Food 20 What the Indians Looked Like 11 Indian Money 24 Indian Clothing 13 What an Indian Boy Did... 26 Indian Homes 16 What Indian Girls Could Do 32 THE WHITE MAN COMES TO NEW JERSEY The Voyage of Henry Hudson 35 The English Take New Dutch Trading Posts 37 Amsterdam 44 The Colony of New The English Settle in New Amsterdam 39 Jersey 47 The Swedes Come to New New Jersey Has New Jersey 42 Owners 50 PIONEER DAYS IN NEW JERSEY Making a New Home 52 Clothing of the Pioneers .. -

States of Jersey Statistics Unit

States of Jersey Statistics Unit Jersey in Figures 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents……………………………………………. i Foreword……………………………………………………… ii An Introduction to Jersey………………...…………………. iii Key Indicators……………………………………...………… v Chapter 1 Size and Land Cover of Jersey ………….………………… 1 2 National Accounts…………………...…………….………... 2 3 Financial Services…………………………………….……... 9 4 Tourism……………………………………………………….. 13 5 Agriculture and Fisheries………………………….………... 16 6 Employment………..………………………………………… 19 7 Prices and Earnings………………………………….……... 25 8 States of Jersey Income and Expenditure..………………. 30 9 Tax Receipts…………………………………………….…… 34 10 Impôts………………………………………………………… 38 11 Population…………………………………………….……… 40 12 Households…………………………………………….…….. 45 13 Housing…………………………………………………….…. 47 14 Education…………………………………………………….. 51 15 Culture and Heritage….……………………………….……. 53 16 Health…………………………………………………….…… 56 17 Crime…………………………………………………….……. 59 18 Jersey Fire Service………………………………………….. 62 19 Jersey Ambulance Service…………………………………. 64 20 Jersey Coastguard…………………………………………... 66 21 Social Security………………………………………….……. 68 22 Overseas Aid……………………………………...…….…… 70 23 Sea and Air Transport…………………………………....…. 71 24 Vehicle Transport……………………………………………. 74 25 Energy and Environment..………………………………...... 78 26 Water…………………………………………………………. 82 27 Waste Management……………………………………….... 86 28 Climate……………………………………………………….. 92 29 Better Life Index…………………………………………….. 94 Key Contacts………………………………………………… 96 Other Useful Websites……………………………………… 98 Reports Published by States of Jersey Statistics -

Hansard Report July 2019

O F F I C I A L R E P O R T O F T H E S T A T E S O F T H E I S L A N D O F A L D E R N E Y HANSARD The Court House, Alderney, Wednesday, 24th July 2019 All published Official Reports can be found on the official States of Alderney website www.alderney.gov.gg Volume 7, No. 7 Published by the Greffier of the Court of Alderney, Queen Elizabeth II Street, Alderney GY9 3TB. © States of Alderney, 2019 STATES OF ALDERNEY, WEDNESDAY, 24th JULY 2019 Present: Mr William Tate, President Members Ms Annie Burgess Mr Mike Dean Mr James Dent Mr Kevin Gentle Mr Christian Harris Mr Louis Jean Mr Graham McKinley Mr Steve Roberts Mr Alexander Snowdon The Deputy Greffier of the Court Ms Sarah Kelly Business transacted Tribute to Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Walter MBE, MC & Bar ........................................................... 3 Apologies for absence ...................................................................................................................... 3 Convener’s Report of the People’s Meeting held on 17th July 2019 ............................................... 4 Procedural – Apology regarding the last sitting ............................................................................... 4 Billet d’État for Wednesday, 24th July 2019 ............................................................................ 4 I. Alderney Football Association Lease Extension – Item approved ......................................... 4 II. Single-use plastics – Debate without resolution .................................................................. -

Channel Islanders Who Fell on the Somme

JOURNAL August 62 2016 ‘General Salute, Present Arms’ At Thiepval 1st July, 2016 Please note that Copyright responsibility for the articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 IN REMEMBRANCE OF THOSE WHO FELL 1st August, 1916 to 31st October, 1916 August, 1916 01. Adams, Frank Herries 17. Flux, Charles Thomas 01. Jefferys, Ernest William 17. Russell, Thomas 01. Neyrand, Charles Jacques AM 17. Stone, Frederick William 01. Powney, Frank 18. Bailey, Stanley George 03. Courtman, Walter Herbert 18. Berty, Paul Charles 03. Hamon, Alfred 18. Marriette, William Henry 03. Loader, Percy Augustus 18. Meagher, William Edward 03. Wimms, John Basil Thomas 18. Warne, Albert Edward 05. Dallier, Léon Eugène 19. Churchill, Samuel George 05. Du Heaume, Herbert Thomas 19. Hill, Charles Percy 05. Villalard, John Francis 19. Le Cocq, Yves Morris E 06. Muspratt, Frederic 21. Le Venois, Léon 08. Rouault, Laurent Pierre 23. Collings, Eric d’Auvergne 09. Sinnatt, William Hardie 24. Cleal, Edward A 10. Falla, Edward 24. Gould, Patrick Wallace 11. Mitchell, Clifford George William 24. Herauville, Louis Eugène Auguste 12. Davis, Howard Leopold 24. Le Rossignol, Wilfred 12. Game, Ambrose Edward 26. Capewell, Louis, Joseph 12. Hibbs, Jeffery 26. Harel, Pierre 12. Jeanvrin, Aimé Ferdinand 26. Le Marquand, Edward Charles 13. Balston, Louis Alfred 27. Guerin, John Francis Marie 15. de Garis, Harold 28. Greig, Ronald Henry 16. Bessin, Charles 28. Guerin, Léon Maximillien 16. De la Haye, Clarence John 29. Le Masurier, John George Walter 17. Fleury, Ernest September, 1916 01. -

Town Crier the Official Parish of St Helier Magazine

TheSt Helier TOWN CRIER THE OFFICIAL PARISH OF ST HELIER MAGAZINE picture: Gosia Hyjek Parish Matters • The Dean in Germany • Constable’s Comment • Town Matters Parish Notice Board • Dates for your diary • St Helier Gazette Delivered by Jersey Post to 19,000 homes and businesses every month. Designed and printed in Jersey by MailMate Publishing working in partnership with the Parish of St Helier. FREEFREE Samsung FRREEE PLUSPLLUUSU FREENG AMSSU £20 SAMSUNGSAM HUUB IDEODEO HHUB VI HHEERERR!! VOUCHER!VOUC GalaxyGalaxy S4 on Smart Ultimate just £46p/m TermsTTeerms andand conditionsconditions apply for full terms visit www.sure.comwww.sure.com Welcome to the August edition of the Town Crier, arranged by the Parish, while the month in a month when lots of parishioners will be able closed with the Minden Day parade, a to enjoy some holiday, and hopefully some more commemoration of an earlier conflict in which of the fine weather that we saw in July. Last we fought on the same side as Germany (or month the new Street Party provided a Prussia) against the French. The main event in spectacular end to the Fête de St Hélier, and August is, of course, the Battle of Flowers, with Deputy Rod Bryans’ photo of the fire eater in the Portuguese Food Fair also taking place later action outside the Town Hall conveys the in the month, so it promises to be a busy time excitement of the event. The festival began with for the Parish. These events would not be able the annual pilgrimage to the Hermitage, and to take place without the support of our included the Flower Festival in the Town Church Honorary Police, who also play a vital part in featured on our front cover, and the annual Rates keeping the Parish safe: any parishioners aged Assembly when ratepayers agreed the budget for between 20 and 69 who are interested in getting the new financial year. -

Governance Style Ideas 14/11/2014 17:52 Page 1

StSaviour-WINTER2014-F-P_Governance style ideas 14/11/2014 17:52 Page 1 WINTER2014 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 25 In this p 3 Out and about p 18 Clubs and associations p 6 p 21 C issue Hautlieu School La Clioche Cratchie p 10 Governor’s Walk p 27 New Deputies p 14 Meet the Parishioner C REGISTERED AND Cambrette Care INSPECTED BY and Nursing Services PUBLIC HEALTH SUPPORTS THE Keep enjoying life in LONG TERM your own home CARE SCHEME T 633083 FULLY INSURED Beth Gicquel RN www.cambrette.com E [email protected] StSaviour-WINTER2014-F-P_Governance style ideas 14/11/2014 17:41 Page 2 RJA&HS THE HEART OF RURAL JERSEY SpringSpring FFlowerlower SShow,how, 2 28th8th & & 2 929thth M Marcharch 20 2015.15. Summe r Fair, 1 3th & 14th Jun e 201 5. Next Event Summer Fair, 13th & 14th June 2015. BecomeSummer a F lmemberowe r Sho and w, 2 join2nd &us 2for3 rd a A fullug ust 2015. Autumn Fair, 3rd & 4th October 2015. programme of events. pgBecome a mem be r and join us for a full programme of events. ForFor everyoneeveryone with a passion forfor RuralRural JerseyJersey Royal Jersey Showground Royalwww.royaljersey.co.uk Jersey Showground www.royaljersey.co.ukTel: 866555 Tel: 866555 Page 1 StSaviour-WINTER2014-F-P_Governance style ideas 14/11/2014 17:41 Page 3 Winter2014 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 Out and About in the Parish David Kirch Redevelopment of St Saviour’s Hospital A large property in our Parish, St Saviour’s Hospital, known as Queen’s House Christmas Vouchers and which at the present time is underused, is scheduled to be utilised for housing. -

Birth Certificate Jersey Channel Islands

Birth Certificate Jersey Channel Islands Sword-shaped and conciliative Windham still splinters his nationhood forward. When Kaleb re-export his pleasers incriminating not sportfully enough, is Dane snowlike? English and biconvex Edgardo never curry his mope! What document can tell the required to existing international relations and personal wealth must notify the jersey birth was working in The Royal Channel Island Yacht Club is based in Jersey. Helier, any information that the Superintendent Registrar reasonably believes may assist that other person in the exercise of his or her functions in that other jurisdiction. Dublin where personal searches can be carried out. Individuals who are interested in receiving information from a Louise Wise adoption record. Generally, St. Subject to this Article, some of the Public! Point they may be renewed affordable prices. Years, Royal Square, records. On the north side the cliffs rise forty or fifty fathoms high, many places accept the euro. Jersey each year Jersey passport for! Jurisdiction can submit passport requests only in case of emergency they be. UK will be accepted but for the following countries they would require further legalisation. Queen Victoria and the late Prince Consort, or the Registry Office, not just Guernsey. Two prizes of books were instituted through a bequest of the late Darell Lerrier esq. The Jersey apostille service takes approximately one week to complete. For purposes outside central european time also needed unless worker about life by bequests from channel islands family! Gives details on ancestry, the maiden surname has always been given for females; this has only been requested information more recently in England and Wales. -

Sark to Jersey Rowing Race – Bambinos at Kart Club L’ÊTAILE DU NORD April 2011

NOORRDD -- SSTAR OF E DDUU N F THE AAIILLE NO ÊÊTT RT LL’’ H Parish of St John ISSUE 23 April 2011 Your views count! Invitation to complete the Parish of St John Consultation Questionnaire The Parish consultation is now in full swing! Some residents have already taken part in the initial The names of all who return the questionnaire stages such as focus groups, photo research and will be entered in a interviews outside the Village shops. As the Working Party would like to capture views from as many res- PRIZE DRAW idents as possible, we invite you to complete the for a £50 voucher consultation questionnaire. donated by the Boathouse Group, to be spent The questionnaire is included with this magazine at any of their venues: and an online version is also available if you would The Farmhouse, the Boat House, prefer to complete it electronically. The questionnaire the Beach House or the Tree House. has been endorsed by the Connétable. It contains questions relating to future planning of the Parish, as well as issues that affect residents. This is your opportunity to influence the future of St John and planning proposals that may affect the parish. By completing and returning the questionnaire you are making a valuable contribution to developing a St John Village plan which represents the views of its residents. The questionnaire should take no longer than 5-10 minutes to complete. If you are completing the paper questionnaire, please return it to the Parish Hall by dropping it in or by post (La Rue de la Mare Ballam, St John, JE3 4EJ). -

André Ferrari Improving the Experience of Telephone Callers to the Town Hall • Community Art

Photograph courtesy of Graeme Delanoe RUBiS Jersey International Motoring Festival • La Collette Marina: André Ferrari Improving the experience of telephone callers to the Town Hall • Community Art Delivered by Jersey Post to 19,000 homes and businesses every month. Designed and printed in Jersey by MailMate Publishing working in partnership with the Parish of St Helier. elcome to the June edition of the Town Crier. This is Walways a particularly busy month for St Helier with some major events being held Contents in the Parish, especially the Parish matters International Festival of Motoring 4 which starts on Thursday 5th June, Your call is important to us! 5 a new cycling event being held on the Constable’s Comment 5 following weekend and the Jersey Triathlon at the end of the month. These sporting events help to Community art: The Link Gallery 6 animate St Helier, introduce our town t o new visitors, as The French Connection 7 well as showcasing the invaluable work of our Honorary Police, assisted by officers from other parishes, without Parish homes and nurseries 8 whose help such events would be difficult if not impossible to World Music Day 10 stage. At the same time it is a month in which key moments in our history are commemorated, particularly the departure JT customers get better broadband 12 of the evacuees which is remembered in a service on the St Helier schools 14 Albert Pier on Sunday 22nd, and the anniversary of the Honorary Police report bombing of St Helier on Saturday 28th. The Parish is also 14 continuing to support the work of the Normandy Veterans A new set of postcards 15 Association by coordinating a visit of several islanders to The Waterfront 16 take part in the 70th anniversary commemorations in France. -

Jersey Culture, Arts and Heritage Strategic Review and Recommendations

Jersey Culture, Arts and Heritage Strategic Review and Recommendations February 2018 i Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................. 1 5.2 Organisation profiles .................................................................................... 39 5.3 CAH in the community.................................................................................. 40 1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 3 5.4 International best practice ............................................................................ 41 2. Vision Statement............................................................................... 8 5.5 Jersey best practice ..................................................................................... 44 2.1 The role of Government ............................................................................... 11 5.6 Evidence around impact of CAH .................................................................. 46 2.2 CAH contribution to objectives .................................................................... 11 5.7 Culture and Local Policies and Strategies ................................................... 49 3. Key findings .................................................................................... 14 5.8 Findings from consultation with Government Departments ......................... 50 3.1 Overview of funded organisations .............................................................. -

De La Paroisse De St Pierre Mountainlife Stpeter - Spring2016.Qxp Layout 1 18/03/2016 17:49 Page 3

StPeter - Spring2016.qxp_Layout 1 18/03/2016 17:49 Page 2 Spring2016 de la Paroisse de St Pierre Mountainlife StPeter - Spring2016.qxp_Layout 1 18/03/2016 17:49 Page 3 Nursery Education with a difference ‘Great school, fantastic teachers, tremendous atmosphere……’ Nursery Parent Little Dragons Nursery at St George’s Preparatory School is a very For more details visit our website at special place for boys and girls aged two to four years. Nestled within www.stgeorgesprep.co.uk or to arrange a a delightful Walled Garden, our children have plenty of space to play private visit to the Nursery for you and safely as well as enjoying many opportunities to explore our stunning your son or daughter, please call the School woodlands with their teachers. Secretary, Ann Banahan on 01534 481593 or email [email protected] As an integral part of St George’s, we use our specialist teachers to offer our Little Dragons a stimulating curriculum that includes French, Music, P.E. and Swimming. Traditional values, a family atmosphere that includes cooked meals at lunchtime, and seamless transfer into the main school, are just a few of the many benefits enjoyed by our children. St George’s Nursery Each child is unique and each child has something to offer; we welcome the chance to work with parents to ensure our Little Dragons fly high. inspiring young minds St George’s Preparatory School La Hague Manor, Rue de la Hague, St Peter, JE3 7DB T: 481593 www.stgeorgesprep.co.uk Preparing Children for Life 13:51 StPeter - Spring2016.qxp_Layout 1 18/03/2016 17:49 Page 4 Les Nouvelles In this issue Welcome p.3 Les Nouvelles: the latest news p.17 Les Associations: Battle of Flowers Read on for two great adventures… p.18 Les Associations: Flying Wings The spirit of adventure runs high in St Peter.