Winwcover1 Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of General Council to Annual Congress 2020

STUC Congress Programme Cover 2020 29/10/2020 09:58 Page 1 The People’s Recovery – Organising for a Fairer Future STUC Congress Programme Cover 2020 29/10/2020 09:58 Page 2 STUC Congress Programme & Report 2020 29/10/2020 11:31 Page 1 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 This Year’s President .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Guide to Congress Arrangements ...................................................................................................................... 3 Tackling Poverty and Inequality by Challenging Corporate Power ..................................................................... 5 Why We Need Lifelong Learning in Scotland ..................................................................................................... 7 Looking Forward to COP26 ................................................................................................................................ 10 Two Hundred and Twenty-Four Linear Metres of STUC History ......................................................................... 12 Let’s Talk Menopause ......................................................................................................................................... 14 STUC Union Reps Awards ................................................................................................................................. -

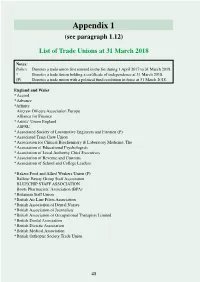

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland 2019-2020

2019-2020 Annual Report of the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland (Covering Period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020). 10-16 Gordon Street Process Colour C: 60 M: 100 Y: 0 Belfast BT1 2LG K: 40 Tel: 028 9023 7773 Pantone Colour 260 Process Colour C: 21 Email: [email protected] M: 26 Y: 61 K: 0 Web: www.nicertoffice.org.uk Pantone Colour 111 TYPEFACE : HELVETICA NEUE First published February 2021 CERTIFICATION OFFICER FOR NORTHERN IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Laid before the Northern Ireland Assembly under paragraph 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 by the Department for the Economy Mr Mike Brennan Permanent Secretary Department for the Economy Netherleigh House Massey Avenue BELFAST BT4 2JP I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 2 Mrs Marie Mallon Chair Labour Relations Agency 2-16 Gordon Street BELFAST BT1 2LG I am required by Article 69(7) of the Industrial Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1992 to submit to you a report of my activities, as soon as practicable, after the end of each financial year. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. Sarah Havlin LLB Certification Officer for Northern Ireland February 2021 3 CONTENTS Review of the year A summary from the Certification Officer for Northern Ireland . -

Rt Hon Liz Truss MP Minister for Women and Equalities Sanctuary

Rt Hon Liz Truss MP contact: Matt Dykes Minister for Women and Equalities direct line: 020 7467 1245 Sanctuary Buildings email: [email protected] 16-20 Great Smith Street London SW1P 3BT 15 July 2021 Dear Minister Equality, respect and safety for LGBT workers As Minister for Women and Equalities, we look to you to be a champion of equality, respect and safety in government. There are more than a million working people who are LGBT+ in the United Kingdom. We write to express our concern at government inaction to address the inequality experienced by LGBT+ people. We were dismayed that you have jettisoned the 2018 LGBT Action Plan, which was based on evidence from more than 100,000 LGBT+ people. And we were disappointed at the decision to disband the LGBT Advisory Panel. Nearly two in five LGBT workers have been harassed or discriminated against by a colleague. A quarter have been discriminated against by their manager, and around one in seven by a client or patient. That rises to nearly half of all trans workers experiencing bullying or harassment at work. Seven in ten LGBT workers have experienced sexual harassment – and one in eight LBT women have experienced sexual assault or rape at work. We urge you to consult with unions on a strategy to make sure workplaces are safe for all LGBT+ people. As a minimum, the government should introduce a new duty on employers to protect workers from harassment by customers and clients. It should also create a specific duty on employers to prevent sexual harassment. -

2015 Scottish Union Learning Annual Report

Scottish Union Learning 5 Annual Report UNION Union Learning: L H E S A I R T N T Developing Scotland’s I N O G C Workforce S Learners’ Quotes “The course has improved my skill “I’ve learned a lot of set and will improve interesting things my employability that will help me in prospects.” my work.” “I found the classroom environment very friendly and felt able to speak and give my opinion. It was overall a very enjoyable experience that I would like to do again.” 2 “A great “Excellent course, introduction. I can’t would really wait to put what we like more of this.” covered today into practice.” “I believe that the work I have “I really loved this completed throughout course. I can see all my studies has the benefits to it. Really contributed to my appreciate the tutors’ recent professional 2015 support, they were opportunities and Annual Report great!” successes.” Front cover photos: Louis Flood and Nick McGowan-Lowe Flood Louis photos: cover Front Introduction Harry Frew, Chair Scottish Union Learning Board This has been another Development Fund and the Equality Rep important and Development project. These initiatives, challenging year for which have been funded as a direct result trade unions, but of the recommendations contained in also a year with a the Working Together Review, will allow number of positive us to develop leadership capacity within developments in the trade union movement in Scotland Scotland, including and work towards increasing the role the establishment of Equality Reps in the private and third Louis Flood Louis of the Fair Work sectors. -

119Th Annual Congress 2016

ANNUAL CONGRESS 2016 DECISIONS BOOKLET (PLEASE RETAIN FOR FUTURE REFERENCE) PAPER A Complete Record of Motions/Amendments/ Composites submitted for consideration at the 2016 Annual Congress and decisions recorded PAPER B Resolutions adopted at the 2016 Annual Congress PAPER C Motions remitted at the 2016 Annual Congress PAPER D Composite withdrawn at the 2016 Annual Congress PAPER E Motions lost at the 2016 Annual STUC Congress PAPER F Motions/Amendment fell at the 2016 Annual STUC Congress PAPER G General Council Statement on the 2016 Scottish Parliament Elections 2016 CONGRESS BUSINESS LIST OF DECISIONS Composites/Resolutions/Motions Decisions Composite A – Manufacturing & Scottish Steel (covering resolution nos. 1 and amendment, 9 and 10) Carried Composite B – Public Finance and Devolved Public Services (covering resolution nos. 2 and 41 and amendment) Carried Composite C – Trade Union Bill and Trade Union Rights (covering resolution nos. 3, 60 and amendment and 61) Carried Composite D – Oil Industry (covering resolution nos. 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) Carried Motion no. 11 – Climate Change and Trade Union Action Remitted Motion no. 12 – Common Ownership Wind Energy Remitted Resolution no. 13 – Renewable Energy Carried Resolution no. 14 – Land Reform Carried Resolution no. 15 – Broadband Change Carried Resolution no. 16 – Cooperative Bank Carried Resolution no. 17 – Heritage Carried Composite F – Access to the Arts (covering Resolution nos. 18 and 19) Carried 2 Composite G – Lack of Dedicated Film Studio Facilities and Support for the Screen Industry in Scotland (covering resolution nos. 20 and 21 and amendment) Carried Resolution no. 22 – Venues Under Threat Carried Composite H – BBC and the Future of Journalism in Scotland (covering resolution nos. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2011-2012

8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page 1 CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2011-2012 www.certoffice.org 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page ii © Crown Copyright 2012 First published 2012 ii 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page iii The Rt Hon Dr Vince Cable MP Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Ed Sweeney Chair of ACAS Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3JJ I am required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 to submit to you both a report on my activities as the Certification Officer during the previous reporting period. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2012. DAVID COCKBURN The Certification Officer 13 June 2012 iii 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page iv iv 8502 C.O. Annual Rep. 11-12 28/06/2012 15:23 Page v Contents Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 5 Entry in the lists and its significance 5 Unions and employers’ associations formed by an amalgamation 6 Trade unions and employers’ associations not on the lists (scheduled bodies) 6 Entry on the lists and schedules 6 Removal from the lists and schedules 7 Additions to the lists and schedules 8 Transfers from the schedules to the list 9 The lists and schedules at 31 March 2012 9 Special register bodies 9 Changes of name of listed trade unions -

Decisions of Conference

Child Poverty 92nd ANNUAL STUC WOMEN’S CONFERENCE MONDAY 28th AND TUESDAY 29th OCTOBER, 2019 CONCERT HALL, PERTH DECISIONS OF CONFERENCE 2 I - RESOLUTIONS CARRIED Resolution no. 1 - Child Poverty "That this Conference notes with alarm that it is estimated almost 1 in 4 children in Scotland are living in poverty and projections of child poverty levels are likely to increase. “These figures are truly hugely disturbing. Over 365,000 children in the UK are destitute and inequality is increasing. In Scotland, the wealth of the 11 billionaires on the Rich List has risen in the last year at much higher proportions than the rest of the UK. “Scotland's children deserve better. We, therefore, call on the STUC Women's Committee to: • work with organisations like Child Poverty Action Group Scotland and The Poverty Alliance; • encourage affiliates to campaign against child poverty causes like Universal Credit; and • lobby the Scottish Government to take sustained necessary action and make considerable investment to meet and exceed statutory targets on child poverty.” Mover: STUC Women’s Committee 3 Resolution no. 2 - Eradicating Child Poverty in Scotland “That this Conference is alarmed at the increasing rates of child poverty throughout Scotland, estimated at around quarter of a million, creating high levels of inequality. “Continual barriers of low income, real term cuts to tax credits and benefits, and the harsh implementation of austerity measures for several years, has resulted in families being faced with the dilemma of whether they should heat their homes, pay their rent or put food on the table. “Reports carried out have shown gender, disability and ethnicity can create barriers to employability and we cannot ignore these are linked to child poverty. -

Trade Union, the Certification Officer

Annual Report of the Report Certification Officer of Annual Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2013-2014 2013-2014 Certification Office for Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 22nd Floor, Euston Tower 286 Euston Tower London NW1 3JJ Tel 020 7210 3734 Fax 020 7210 3612 e-mail: [email protected] www.certoffice.org CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2013-2014 www.certoffice.org © Crown Copyright 2014 First published 2014 ii The Rt Hon Dr Vince Cable MP Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Sir Brendan Barber Chair of ACAS Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3JJ I am required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 to submit to you both a report on my activities as the Certification Officer during the previous reporting period. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014. DAVID COCKBURN The Certification Officer 24 June 2014 iii iv Contents Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 5 Entry in the lists and its significance 5 Unions and employers’ associations formed by an amalgamation 6 Trade unions and employers’ associations not on the lists (scheduled bodies) 6 Removal from the lists and schedules 6 Additions to the lists and schedules 8 The lists and schedules at 31 March 2014 8 Special register bodies 9 Changes of name of listed trade unions -

Scottish Union Learning Annual Report 2018 Learners’ Quotes

Scottish Union Learning Annual Report 2018 Learners’ Quotes I would Great course, recommend very informative this course and well to anyone. delivered. Good mix of Enjoyed this visuals, theory very much. and practice. Looking forward Thoroughly to putting into enjoyed the practice. course. 2 Contents Introduction 4 Structure 5 The Board 6 Advisory Groups 7 The Development Fund 8 The Learning Fund 10 Improving Everyday Skills 16 Digital Unions: Cyber Resilience 19 Fair Work: Leadership & Equality 21 Apprenticeships 24 Awards 25 Conferences & Events 28 Working with Partners 30 TUC Education 31 Resources & Communications 32 Contacts 35 3 Introduction Peter Hunter, Chair, Scottish Union Learning Board This has It is important to know what drives been another this work, and throughout the year successful, I have engaged with SUL and the though unions involved, to understand how challenging, they work and the union values they year for demonstrate in supporting learners. union Their approach helps to remove learning. barriers, create opportunity, promote I would like Fair Work, and ultimately make a to take this change to the lives of workers, not opportunity only in their jobs, but also in their to thank personal, social and community our funders, Scottish Government, lives. The reason I am sharing this and our major sponsors, Skills with you in this Annual Report is Development Scotland, Scottish primarily to highlight the discipline Qualifications Authority, and The and effective focus of those involved Open University in Scotland, for their in union learning, but also to make continued support. a point about strategy - which can sometimes get lost in the busy day- Throughout the year, Scottish Union to-day operational objectives. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2014-2015

Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2014-2015 www.gov.uk/certificationofficer CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2014-2015 www.gov.uk/certificationofficer © Crown Copyright 2015 First published 2015 ii The Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Sir Brendan Barber Chair of ACAS Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3JJ I am required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 to submit to you both a report on my activities as the Certification Officer during the previous reporting period. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2015. DAVID COCKBURN The Certification Officer 6 July 2015 iii iv Contents Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 5 Entry in the lists and its significance 5 Unions and employers’ associations formed by an amalgamation 6 Trade unions and employers’ associations not on the lists (scheduled bodies) 6 Removal from the lists and schedules 6 Additions to the lists and schedules 7 The lists and schedules at 31 March 2015 8 Special register bodies 10 Changes of name of listed trade unions and employers’ associations 10 Definition of a trade union 10 Definition of an employers’ association 11 2 Trade Union Independence 12 The statutory provisions 12 Criteria 13 Applications, decisions, reviews and appeals 13 3 Annual -

SERTUC Directory.Pdf

More than two million trade union members live and work in London, the South East and the East of England. Each and every one of them has made a personal decision to join a collective to defend and extend their and other workers’ rights at work. We have 60,000 reps in our workplaces, who carry their expertise and values into the communities in which they live. The Government’s austerity programme is not fair, it is not necessary – in fact it is plain stupid and very nasty. No economy like ours in all history has ever cut its way out of a recession. Alongside community groups and service users we must create dynamic coalitions and smart campaigns to defend jobs and services. We have an alternative strategy that that will create jobs and increase social justice and we must campaign to gain more traction for it and foreword confidence in it. Anything and everything that workers have Effective communication is a critical feature of gained was won by organisation, campaigning effective campaigning. SERTUC has produced and struggle – not gifted to us by enlightened this third Regional Directory as a tool to bosses or progressive governments. increase contact between unions, as well as to facilitate contact between unions, trades Today we face the greatest challenge to the councils, community groups and service users. interests of the working class for a generation. In a few months the Coalition Government has The SERTUC regional office is always willing to shelved whatever industrial strategy we had. It offer advice as to whom a union should contact has announced the abolition of the Regional to further joint working.