New Data on the Occurrence of Panthera Pardus in the Talysh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resolution, Multi-Proxy Peat Record from NW Iran: the Hand That Rocked the Cradle of Civilization?

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280075839 Abrupt climate variability since the last deglaciation based on a high- resolution, multi-proxy peat record from NW Iran: The hand that rocked the Cradle of Civilization? Article in Quaternary Science Reviews · August 2015 DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.07.006 CITATIONS READS 41 1,081 12 authors, including: Arash Sharifi Ali Pourmand University of Miami University of Miami 74 PUBLICATIONS 166 CITATIONS 75 PUBLICATIONS 1,062 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Elizabeth Canuel Larry C. Peterson Virginia Institute of Marine Science University of Miami 131 PUBLICATIONS 5,297 CITATIONS 176 PUBLICATIONS 10,501 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Madison Group Project View project ANR-PALEOPERSEPOLIS View project All content following this page was uploaded by Ali Pourmand on 10 September 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Quaternary Science Reviews 123 (2015) 215e230 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Abrupt climate variability since the last deglaciation based on a high-resolution, multi-proxy peat record from NW Iran: The hand that rocked the Cradle of Civilization? * Arash Sharifi a, b, , Ali Pourmand a, b, Elizabeth A. Canuel c, Erin Ferer-Tyler c, Larry C. Peterson b, Bernhard Aichner d, Sarah J. Feakins d, Touraj Daryaee e, Morteza Djamali f, Abdolmajid Naderi Beni g, Hamid A.K. Lahijani g, Peter K. Swart b a Neptune Isotope Laboratory (NIL), Department of Marine Geosciences, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL 33149-1098, USA b Department of Marine Geosciences, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (RSMAS), University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL 33149-1098, USA c Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William & Mary, P.O. -

First Horseback Azerbaidjan Expedition 2018 Indiv

Pioneering Azerbaïdjan Horse Expedition CAUCASUS EXPEDITIONS Contact : Audrey Bogini [email protected] [email protected] CAUCASUS EXPEDITIONS 2018 Azerbaidjan shares its border with Georgia, Dagestan, Iran and Armenia. It stretches from the North with the Great Caucasus Mountains to the hilly picturesque Hirkan Natio- nal Park and the Talysh mountains in the South. It is the only country of the whole Cauca- sus chain where you can cross the southern slopes to the northern slopes. In the Caucasus area, Azerbaidjan is nowadays the wildest country for nature activities. Focused on the oil business the decision makers were not thinking about developing sport / outdoors tourism. The core of our itinerary is the self sufficient horseback trek in the very wilderness of the Great Caucasus Mountains. During our route we ride over passes, on crest or high pla- teau, between mountains lakes, through untouched forest and wild rivers. We will be accompanied by the local Lezgian people who know by heart the incredible Ismaili Na- tional park. Your target is to reach the village of Lahic settled by the Tat people coming originally from Iran. Mountains horses are the only way of transportation in the mountains, not only for people but also for different kind of material, wood, stones … . We will choose our route day by day in accordance with the weather, pathway and snow conditions. Each day will CAUCASUS EXPEDITIONS 2018 be an adventure and each trip will offer a new itinerary…be different and the choice is simply huge. Around our Caucasian cavalcades this trip offers a rich mix of nature and culture, dif- ferent kind of ecosystems and landscapes from the green mountains to the volcanic de- sert, old and new contrasting the country’s ancient heritage with its modern buildings in Baku, the pure unspoiled nature facing the former oil industrial lands. -

Spatial Diversity in the Diet of the Eurasian Eagle Owl Bubo Bubo in Iran

Podoces, 2014, 9(1): 7 –21 PODOCES 2014 Vol. 9, No. 1 Journal homepage: www.wesca.net Spatial Diversity in the Diet of the Eurasian Eagle Owl Bubo bubo in Iran Ján Obuch Comenius University in Bratislava, Detached Unit, SK-038 15 Blatnica, Slovakia. Article Info Abstract Original Research During five stays in Iran, the author collected remnants of the diet from seven species of owls. The most numerous were samples from the Eurasian Eagle Received 25 March 2014 Owl Bubo bubo , which were found in 38 sites, usually on rocky cliffs where Accepted 14 January 2015 the owls breed or where they roost during the day. A total of 7,862 items of prey were analysed. Mammals predominated (Mammalia, 56 species, Keywords 77.0%), and the species representation of birds was diverse (Aves, more than Eurasian Eagle Owl 100 species, 15.3%); lower vertebrates were hunted less often (Amphibia, Bubo bubo Reptilia, Pisces, 5.0%), while invertebrates (Evertebrata, 2.7%) were an Diet occasional food supplement. The most commonly represented rodents Iran (Rodentia) in the Elborz and Talysh Mountains were: Snow Vole Chionomys nivalis , Steppe Field Mouse Apodemus witherbyi and Common Vole Microtus obscurus; in the northern part of the Zagros Mountains: Brandt’s Hamster Mesocricetus brandti , Williams’ Jerboa Allactaga williamsi and Setzer’s Mouse-tailed Dormouse Myomimus setzeri ; in the central wetter part of the Zagros: Persian Jird Meriones persicus , Tristam’s Jird Meriones tristrami , Transcaucasian Mole Vole Ellobius lutescens and Grey Hamster Cricetulus migratorius ; in the drier part of the Zagros: Libyan Jird Meriones libycus , Sundevall’s Jird Meriones crassus and Indian Gerbil Tatera indica ; in the southern part of the Zagros in Fars Province: Iranian Vole Microtus irani , the rats Rattus rattus and R. -

Quantifying Arabia–Eurasia Convergence Accommodated in the Greater Caucasus by Paleomagnetic Reconstruction ∗ A

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 482 (2018) 454–469 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Quantifying Arabia–Eurasia convergence accommodated in the Greater Caucasus by paleomagnetic reconstruction ∗ A. van der Boon a, , D.J.J. van Hinsbergen a, M. Rezaeian b, D. Gürer a, M. Honarmand b, D. Pastor-Galán a,c, W. Krijgsman a, C.G. Langereis a a Utrecht University, The Netherlands b Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences, Zanjan, Iran c Center for Northeast Asian Studies, Tohoku University, Japan a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Since the late Eocene, convergence and subsequent collision between Arabia and Eurasia was accommo- Received 23 June 2017 dated both in the overriding Eurasian plate forming the Greater Caucasus orogen and the Iranian plateau, Received in revised form 20 September and by subduction and accretion of the Neotethys and Arabian margin forming the East Anatolian plateau 2017 and the Zagros. To quantify how much Arabia–Eurasia convergence was accommodated in the Greater Accepted 9 November 2017 Caucasus region, we here provide new paleomagnetic results from 97 volcanic sites (∼500 samples) in Available online xxxx ∼ ◦ Editor: A. Yin the Talysh Mountains of NW Iran, that show 15 net clockwise rotation relative to Eurasia since the Eocene. We apply a first-order kinematic restoration of the northward convex orocline that formed to Keywords: the south of the Greater Caucasus, integrating our new data with previously published constraints on tectonic rotations rotations of the Eastern Pontides and Lesser Caucasus. -

Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV

BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 Sponsored by VELIYEV RUSTAM SALEH oglu T ranslated by ZAHID MAHAMMAD oglu AHMADOV Edited by FARHAD MAHAMMAD oglu MUSTAFAYEV Budagov B.A. Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia. - Baku “Elm”, 1997, -1 7 4 p. ISBN 5-8066-0757-7 The geographical toponyms preserved in the immense territories of Turkic nations are considered in this work. The author speaks about the parallels, twins of Azerbaijani toponyms distributed in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Altay, the Ural, Western Si beria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, the Crimea, Chinese Turkistan, etc. Be sides, the geographical names concerned to other Turkic language nations are elucidated in this book. 4602000000-533 В ------------------------- 655(07)-97 © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 A NOTED SCIENTIST Budag Abdulali oglu Budagov was bom in 1928 at the village o f Chobankere, Zangibasar district (now Masis), Armenia. He graduated from the Yerevan Pedagogical School in 1947, the Azerbaijan State Pedagogical Institute (Baku) in 1951. In 1955 he was awarded his candidate and in 1967 doctor’s degree. In 1976 he was elected the corresponding-member and in 1989 full-member o f the Azerbaijan Academy o f Sciences. Budag Abdulali oglu is the author o f more than 500 scientific articles and 30 books. Researches on a number o f problems o f the geographical science such as geomorphology, toponymies, history o f geography, school geography, conservation o f nature, ecology have been carried out by academician B.A.Budagov. He makes a valuable contribution for popularization o f science. -

Culture of Azerbaijan

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CULTURE OF AZERBAIJAN CONTENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................................................................................................. 3 II. MATERIAL CULTURE ................................................................................................................... 5 III. MUSIC, NATIONAL MUSIC INSTRUMENTS .......................................................................... 7 Musical instruments ............................................................................................................................... 7 Performing Arts ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Percussion instruments ........................................................................................................................... 9 Wind instruments .................................................................................................................................. 12 Mugham as a national music of Azerbaijan ...................................................................................... 25 IV. FOLKLORE SONGS ..................................................................................................................... 26 Ashiqs of Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 27 V. THEATRE, -

The Silk Road

Introduction Page 5 History Background The Silk Road Today A Mosaic of Tourism Destinations Part 1 Heritage Page 13 CONTENTS THE SILK ROAD Heritage Sites Heritage Cities Tourism Products Part 2 Nature Page 29 Natural Sites, Adventure and Sport Tourism, Special Interest Tourism, Hunting and Fishing Part 3 Customs Page 39 Traditions and Culture, Crafts, Cuisine Tips for the Traveller Page 49 Travel Tips Country Information Silk Road, Southern, Middle and Northern Routes 5 The Silk Road - History / Background The Greatest Overland Route in History Over many centuries, traders, nomadic warriors, prophets, emigrants and adventurers traversed the Silk Road that crossed much of the known world from Europe to the Far East, a 12,000-kilometer route through some of the harshest terrains on earth. But the huge deserts, endless steppes and towering mountains were only the physical barriers that the intrepid travellers had to surmount; there were also brigands, wars, unfriendly potentates, natural disasters and disease. Commerce was the chief activity along the route and although it is known as the Silk Road, that precious commodity was only one of the many goods traded from the Mediterranean to the Pacific. Caravans loaded with everything from glass, furs, porcelain, perfume, gems, and carpets to slaves, livestock, spices, mirrors, paper, gunpowder and a thousand other things moved East and West along what has been described as the greatest overland route in the history of mankind. Scholars say the first recorded mention of the Silk Road dates back to around 100 BC when a Chinese expedition set off west to purchase horses in Central Asia where they learned that the silk they had brought was highly prized in the bazaars. -

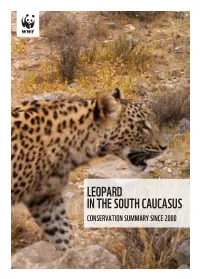

LEOPARD in the SOUTH CAUCASUS CONSERVATION SUMMARY SINCE 2000 Text: N

LEOPARD IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS CONSERVATION SUMMARY SINCE 2000 Text: N. Zazanashvili (WWF-Caucasus), K. Manvelyan (WWF Armenia), E. Askerov (WWF Azerbaijan) and A. Heidelberg (WWF-Germany) Leopard photos: WWF’s camera-traps Map: G. Beruchashvili, WWF-Caucasus GIS Unit Publisher: WWF-Caucasus: M. Aleksidze str. 11, 0193 Tbilisi, Georgia; E-mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +995 32 223 75 00. Published by: TM Group: K. Kekelidze str. 25, 0179 Tbilisi, Georgia; E-mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +995 32 272 90 52 ISBN 978-9941-8-2318-3 Copyright © 2020 WWF No part of this publication can be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the WWF-Caucasus. INTRODUCTION One of the most biologically rich ecoregions on earth, the Caucasus is ranked among the planet’s 36 most diverse and endangered hotspots (Mittermeier et al. 2004). The Caucasus is also a globally significant centre of cultural diversity, where a multitude of ethnic groups and languages intermingle over a relatively small area. The ecoregion covers three South Caucasus countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia), North Caucasus part of Russian Federation, north-eastern Turkey and part of north-western Iran. Main mountain ranges include the Greater Caucasus (with the highest peak of the Caucasus being Mt. Elbrus, 5.642 m above sea level), the Lesser Caucasus mountain chain and Talysh Mountains and western part of Alborz Mountains. The 2019 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (www.redlist.org) identifies 86 species of globally threatened vertebrates in the Caucasus, among them 17 species of mammals, including Leopard (Panthera pardus). -

NW Iran): Paleomagnetic T Constraints ⁎ M

Tectonophysics 786 (2020) 228459 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Post-Eocene coupled oroclines in the Talesh (NW Iran): Paleomagnetic T constraints ⁎ M. Rezaeiana, , C.B. Kuijperb, A. van der Boonb,c, D. Pastor-Galánb,d,e, L.J. Cottonf, C.G. Langereisb, W. Krijgsmanb a Department of Earth Sciences, Institute for Advanced Studies in the Basic Sciences, Zanjan, Iran b Paleomagnetic Laboratory Fort Hoofddijk, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands c Geomagnetic Laboratory, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom d Center for Northeast Asian Studies, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan e Frontier Research Institute for Interdisciplinary Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan f School of Environment, Geography and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth,United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The Talesh Mountains (NW Iran) witnessed a long deformation history from the Triassic Cimmerian orogeny to Paleomagnetism the ongoing Arabia-Eurasia collision. This protracted multi-stage deformation has generated a remarkably Arabia-Eurasia collision curved orogen with a puzzling kinematic and deformational history. In this study, we investigate the origin of Orocline the Talesh curvature through paleomagnetic analyses on rocks of Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic age. Our Aras - Lahijan faults results indicate that at least two major, large-scale, vertical-axis-rotations took place since the Late Cretaceous: Tethys 1) a pre-Eocene 73° ± 17° clockwise rotation and 2) post-Eocene differential rotations that formed the Z-shaped Talesh mountain belt within a crustal-scale shear zone. The latter involved an increasing amount of clockwise (CW) rotation from south (16°) to north (48°). The orocline formation likely started during the Oligocene where an approximately east-west oriented mountain belt was buckled by the Arabia-Eurasia collision, with Arabia acting as a rigid indenter and the South Caspian basin as a rigid backstop. -

Georgia: Pilot Programme to Deliver a Carbon Neutral and Sustainable Hydropower Project Project Number: C30272/AUS1-2014-08-04

Georgia: Pilot Programme to Deliver a Carbon Neutral and Sustainable Hydropower Project Project number: C30272/AUS1-2014-08-04 Interim Report FS Consult Envi Consulting LLC 21.12.2015 Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Project cornerstones ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2. General characteristics of the Kazbegi district area ................................................................ 2 1.2.1. Kazbegi district .................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.2. Geomorphology ................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.3. Geology ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.4. Soils ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.5. Mineral resources ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2.6. Climate ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2.7. Glaciers ............................................................................................................................... -

²êî²æ²üæ² Takhtajania Тахтаджяния

вÚÎ²Î²Ü ´àôê²´²Ü²Î²Ü ÀÜκðàôÂÚàôÜ Ð²Ú²êî²ÜÆ Ð²Üð²äºîàôÂÚ²Ü ¶ÆîàôÂÚàôÜܺðÆ ²¼¶²ÚÆÜ ²Î²¸ºØƲÚÆ ²© ²Êî²æÚ²ÜÆ ²Üì²Ü ´àôê²´²ÜàôÂÚ²Ü ÆÜêîÆîàôî ARMENIAN BOTANICAL SOCIETY INSTITUTE OF BOTANY AFTER A. TAKHTAJYAN OF NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES REPUBLIC ARMENIA АРМЯНСКОЕ БОТАНИЧЕСКОЕ ОБЩЕСТВО ИНСТИТУТ БОТАНИКИ ИМ. А. ТАХТАДЖЯНА НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЙ АКАДЕМИИ НАУК РЕСПУБЛИКИ АРМЕНИЯ Â²Êî²æ²ÜƲ äñ³Ï 4 TAKHTAJANIA Issue 4 ТАХТАДЖЯНИЯ Выпуск 4 ºñ¨³Ý Yerevan Ереван 2018 УДК 581. 9 ББК 28.5 Т244 Печатается по решению редакционного совета TAKHTAJANIA Редакционный совет: Варданян Ж. А., Грёйтер В. (Палермо), Аверьянов Л. В. (Санкт-Петербург), Гельтман Д. В. (Санкт-Петербург), Витек Э. (Вена), Осипян Л. Л., Нанагюлян С. Г. Редакционная коллегия: Оганезова Г. Г. (главный редактор), Оганесян М. Э., Файвуш Г. М., Элбакян А. А. (ответственный секретарь) Takhtajania /Армянское ботаническое общ-во, Институт ботаники им. А. Тахтаджяна НАН РА; Т 244 Ред. коллегия: Оганезова Г. Г. и др. – Ер.: Арм. ботаническое общество, 2018. Вып. 4. – 132 с. Основной тематикой сборника являются систематика растений, морфология, анатомия, флористика, эволюция, палинология, кариология, палеоботаника, геоботаника, биология и другие проблемы. 0040, Армения, Ереван, ул. Ачаряна 1, Армянское ботаническое общество (редакция Takhtajania). Телефон: (37410) 61 42 41; e-mail: [email protected] ВАК Армении включает Тахтаджания в перечень периодических научных изданий, в которых могут быть опубликованы основные результаты и положения для кандидатских диссертаций Рецензируемое издание Следующие выпуски Тахтаджания будут выходить ежегодно только в электронном виде Электронный вариант доступен на сайте www.flib.sci.am ISBN 978 –99941–2–564–7 УДК 581. 9 ББК 28.5 © Арм. -

Azerbaijan) in the Central Botanical Garden (Azerbaijan)

European Botanic Gardens in a Changing World: Insights into EUROGARD VI Ex situ conservation of endangered geophytes of the Hirkan National Park (Azerbaijan) in the Central Botanical Garden (Azerbaijan) Rashad Salimov Allahverdioglu 1,2 , Ibadli Oruc Velioglu 1 1 Laboratory of Rare and Endangered Plants, Central Botanical Garden of Azerbaijan, National Academy of Sciences, AZ1073, Badamdar Highway 40, Baku, Azerbaijan, [email protected] 2 Department of Biology, Qafqaz University, Baku-Sumqayit Road 16-km Xirdalan, Baku AZ0101, Azerbaijan Keywords : tuber, rhizome, rare species, endemic, Caucasus, Red Book Abstract The Hirkan National Park (HNP) which includes the mountainous Talish region is a unique natural complex. The HNP was established to preserve the nature of this area, to protect relict and endemic plants of the Tertiary period and characteristic flora and fauna types, which were not affected by the Pliocene and Pleistocene glaciations (included in ‘ The Red Book of Azerbaijan ’) [1] and for monitoring the environment, public awareness and the creation of favourable conditions for research, tourism and recreation. The HNP is a forest with a rich floristic composition, including 150 endemic species out of a total of 435 species of trees and bushes. In the research area, more than 15 geophyte species are endemic plants of the Caucasus or Azerbaijan. Some geophyte species are Allium lenkoranicum Miscz. ex Grossh., A. talyschense Miscz. ex Grossh., Bellevalia fominii Woronow, Ornithogalum hyrcanum Grossh., Fritillaria grandiflora Grossh., Crocus caspius Fisch. & C.A. Mey., Iris helena (C. Koch) C. Koch, Himantoglossum formosum (Stev.) C. Koch, Ophrys oestrifera Bieb. The 92 geophyte species identified and registered in the HNP belong to 21 families and 46 genera, including 33 rare and endangered species, of which 11 species are included in ‘ The Red Book of Azerbaijan’ .