Comment on Aziz Rana, the Two Faces of American Freedom Nancy L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

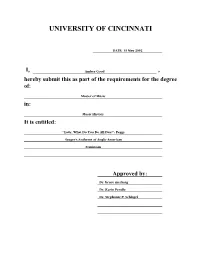

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: 13 May 2002 I, Amber Good , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Music in: Music History It is entitled: ``Lady, What Do You Do All Day?'': Peggy Seeger's Anthems of Anglo-American Feminism Approved by: Dr. bruce mcclung Dr. Karin Pendle Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 1 “LADY, WHAT DO YOU DO ALL DAY?”: PEGGY SEEGER’S ANTHEMS OF ANGLO-AMERICAN FEMINISM A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2002 by Amber Good B.M. Vanderbilt University, 1997 Committee Chair: Dr. bruce d. mcclung 2 ABSTRACT Peggy Seeger’s family lineage is indeed impressive: daughter of composers and scholars Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger, sister of folk icons Mike and Pete Seeger, and widow of British folksinger and playwright Ewan MacColl. Although this intensely musical genealogy inspired and affirmed Seeger’s professional life, it has also tended to obscure her own remarkable achievements. The goal of the first part of this study is to explore Peggy Seeger’s own history, including but not limited to her life within America’s first family of folk music. Seeger’s story is distinct from that of her family and even from that of most folksingers in her generation. The second part of the thesis concerns Seeger’s contributions to feminism through her songwriting, studies, and activism. -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

Band/Surname First Name Title Label No

BAND/SURNAME FIRST NAME TITLE LABEL NO DVD 13 Featuring Lester Butler Hightone 115 2000 Lbs Of Blues Soul Of A Sinner Own Label 162 4 Jacks Deal With It Eller Soul 177 44s Americana Rip Cat 173 67 Purple Fishes 67 Purple Fishes Doghowl 173 Abel Bill One-Man Band Own Label 156 Abrahams Mick Live In Madrid Indigo 118 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Swallow 033 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Ace 084 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues/The Good Times Killin' Me Ace 096 Abshire Nathan The Good Times Killin' Me Sonet 044 Ace Black I Am The Boss Card In Your Hand Arhoolie 100 Ace Johnny Memorial Album Ace 063 Aces Aces And Their Guests Storyville 037 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 022 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 033 Aces No One Rides For Free El Toro 163 Aces The Crawl Own Label 177 Acey Johnny My Home Li-Jan 173 Adams Arthur Stomp The Floor Delta Groove 163 Adams Faye I'm Goin' To Leave You Mr R & B 090 Adams Johnny After All The Good Is Gone Ariola 068 Adams Johnny After Dark Rounder 079/080 Adams Johnny Christmas In New Orleans Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny From The Heart Rounder 068 Adams Johnny Heart & Soul Vampi 145 Adams Johnny Heart And Soul SSS 068 Adams Johnny I Won't Cry Rounder 098 Adams Johnny Room With A View Of The Blues Demon 082 Adams Johnny Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me Rounder 097 Adams Johnny Stand By Me Chelsea 068 Adams Johnny The Many Sides Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Sweet Country Voice Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Tan Nighinggale Charly 068 Adams Johnny Walking On A Tightrope Rounder 089 Adamz & Hayes Doug & Dan Blues Duo Blue Skunk Music 166 Adderly & Watts Nat & Noble Noble And Nat Kingsnake 093 Adegbalola Gaye Bitter Sweet Blues Alligator 124 Adler Jimmy Midnight Rooster Bonedog 170 Adler Jimmy Swing It Around Bonedog 158 Agee Ray Black Night is Gone Mr. -

Tradition Label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography

Tradition label Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Tradition Label Discography The Tradition Label was established in New York City in 1956 by Pat Clancy (of the Clancy Brothers) and Diane Hamilton. The label recorded folk and blues music. The label was independent and active from 1956 until about 1961. Kenny Goldstein was the producer for the label during the early years. During 1960 and 1961, Charlie Rothschild took over the business side of the company. Clancy sold the company to Bernard Solomon at Everest Records in 1966. Everest started issuing albums on the label in 1967 and continued until 1974 using recordings from the original Tradition label and Vee Jay/Horizon. Samplers TSP 1 - TraditionFolk Sampler - Various Artists [1957] Birds Courtship - Ed McCurdy/O’Donnell Aboo - Tommy Makem and Clancy Brothers/John Henry - Etta Baker/Hearse Song - Colyn Davies/Rodenos - El Nino De Ronda/Johnny’s Gone to Hilo - Paul Clayton/Dark as a Dungeon - Glenn Yarbrough and Fred Hellerman//Johnny lad - Ewan MacColl/Ha-Na-Ava Ba-Ba-Not - Hillel and Aviva/I Was Born about 10,000 Years Ago - Oscar Brand and Fred Hellerman/Keel Row - Ilsa Cameron/Fairy Boy - Uilleann Pipes, Seamus Ennis/Gambling Suitor - Jean Ritchie and Paul Clayton/Spiritual Trilogy: Oh Freedom, Come and Go with Me, I’m On My Way - Odetta TSP 2 - The Folk Song Tradition - Various Artists [1960] South Australia - A.L. Lloyd And Ewan Maccoll/Lulle Lullay - John Jacob Niles/Whiskey You're The Devil - Liam Clancy And The Clancy Brothers/I Loved A Lass - Ewan MacColl/Carraig Donn - Mary O'Hara/Rosie - Prisoners Of Mississippi State Pen//Sail Away Ladies - Odetta/Ain't No More Cane On This Brazis - Alan Lomax, Collector/Railroad Bill - Mrs. -

7^ Lawrentian

STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSPAPER SECTION 81fc STATE STRLfcT MADISON 6 9 « I S . Three Candidates Battle for Top SEC Post Tomorrow Davidson, Ford and Lubenow Petition lor Presidency 7 By AL SALTZSTE1N ^ Lawrentian Lawrence students will go to the polls tomorrow to Vol. 81—No. 15 Lawrence College, Appleton, Wisconsin Thursday, February 15, 1962 select the new president of the Student Executive Coun cil, and to vote on a proposed amendment to the gov erning body’s constitution increasing the Council’s leg islative power somewhat. Divergence in Styles Seen SPECIAL ISSUE The election is the first in He is the author of the refer SATURDAY three years to offer the voter endum on tomorrow’s ballot, A special issue of the a choice of candidates. Jun Sandy is active in the drama In Modern Jazz Quartet Lawrentian on Saturday ior John Davidson and soph department, and participated By FRITZ HOLM QUIST will carry the results of omores Sandy Ford and Joe in the last two theater pro tomorrow’s election. ductions. The Lawrence campus will soon be privileged to Lubenow have been placed on the ballot after submitting a He views the job of presi hear one of the most stimulating instrumental groups petition cotnaining fifty dent as one centralization of in all of American music and most certainly in the names each to the Council power within existing frame w'orld of jazz. On Friday, Feb. 23, the Modern Jazz Monday night. Elizabeth work of the body. He hopes Quartet will give a concert at 8:30 p.m. -

Society for American Music Forty-Second Annual Conference

Society for American Music Forty-Second Annual Conference Hosted by Northeastern University and Babson College Hyatt Regency Cambridge 9–13 March 2016 Boston, Massachusetts Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), the early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. Each member lists current topics or projects that are then indexed, providing a useful means of contact for those with shared interests. -

Volume 81, Number 16, February 17, 1962

Run-off,· Amendment f!!!,,?,,wum~~,~,~~,~,~' IIIIII IIIII IIIIIIIIIIJ' in.rn111111111111u11111111111111111111111111111u1 Fails by Ten Council Lets Liz Campaign; f4' Lawre~(i;;"'' :T·urnout 'Sets Voting Mark The student body turned down an amendment to . Vol. 81 No. 16 · Lawrence College A ' PP1 eton , Wi sconsin S broaden the powers of the SEC, and failed to grant a a turday, Fe1bruary 17, 1962 1:1a.iority to a presidential candidate in Friday's elec tion. Eli zabeth Cole and Joe Lubenow the candidates ~irk Dr:1-ws Large Crowd; COMMITTEE receiving the highest number of vote; in the primary, P0S'1'S OPEN were placed on the ballot for today's run-off election. Liberal Philosophy Candidates for SEC com Bia.st$ mittee chairmans'hips must The SEC, meeting in an emergency session last night By ALEX WILDE submi_t pet itions containing agreed to place Miss Cole's name on the ballot and · A large and alert audience heard Dr R . qualifications and plat passed a ~tandi:1g rule allowing her' to campaign. 'until deliver _his provoc~tive interpretation of ,;Di u_sstell Kirk forms to the new SEC the 1:1eetmg Miss Cole had campaigned as, a write-in Liberalism m .Foreign Poli. cy" in the Uni·o n 1as.srn t Segrateclunday President by midnight candidate. 11 Th Sa~urday, February 24 '. F· eb ruary . e promment con servative th· k l ' Friday's turnout was the largest in Lawrence's his d · d t . rn er crew 1962 All candidates must 01,1er ene h un 1e spe.c ators ' from Appleto n an d near- tory. -

![Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [Audiotapes]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6000/guide-to-the-moses-moon-collection-audiotapes-3916000.webp)

Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [Audiotapes]

Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [audiotapes] NMAH.AC.0556 Wendy Shay Partial funding for preservation and duplication of the original audio tapes provided by a National Museum of American History Collections Committee Jackson Fund Preservation Grant. Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Original Tapes.......................................................................................... 6 Series 2: Preservation Masters............................................................................. -

Odetta and the Blues Mp3, Flac, Wma

Odetta Odetta And The Blues mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Blues Album: Odetta And The Blues Country: Australia Released: 1962 Style: Vocal MP3 version RAR size: 1224 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1383 mb WMA version RAR size: 1838 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 239 Other Formats: AHX ASF DTS ADX AA FLAC MP3 Tracklist A1 Hard, Oh Lord 4:05 A2 Believe I'll Go 3:03 A3 Oh, Papa 3:16 A4 How Long Blues 2:06 A5 Hogan's Alley 2:09 A6 Leavin' This Mornin' 2:46 B1 Oh, My Babe 4:19 B2 Yonder Comes The Blues 2:48 B3 Make Me A Pallet On The Floor 3:47 B4 Weeping Willow Blues 2:35 B5 Go Down Sunshine 2:17 B6 Nobody Knows When You're Down And Out 2:19 Credits Bass – Ahmed Abdul-Malik Clarinet – Herb Hall Drums – "Shep" Sheppard* Piano – Dick Wellstood Producer – Orrin Keepnews Trombone – Vic Dickenson Trumpet – Buck Clayton Vocals – Odetta Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Odetta And The Blues RLP 9417 Odetta Riverside Records RLP 9417 US 1962 (LP, Album) Odetta And The Blues Hallmark Music & 713502 Odetta 713502 Europe 2013 (CD, Album, RE) Entertainment Odetta And The Blues RLP 9417 Odetta Riverside Records RLP 9417 US 1962 (LP, Album) Odetta And The Blues RM 417 Odetta Riverside Records RM 417 US Unknown (LP, Mono) R/S-3007 Odetta Sings The Blues (LP) Riverside Records R/S-3007 US 1968 Related Music albums to Odetta And The Blues by Odetta Odetta - At Town Hall Odetta - At Carnegie Hall Odetta - Odetta Sings Dylan Odetta - To Ella Odetta - It's A Mighty World Willie Brown / Son House - Make Me A Pallet On The Floor / Shetland Pony Blues Odetta - At The Gate Of Horn Giuseppe Pino, Various - Black & Blues Odetta - Spirituals For Christmas Odetta - Sings Ballads And Blues. -

The History of Rock Music: 1955-1966

The History of Rock Music: 1955-1966 Genres and musicians of the beginnings History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Trouble in Paradise 1961-1964 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The Folk Revival TM, ®, Copyright © 2003 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The most significant event of the USA music scene at the turn of the decade was the folk revival. Launched in 1958 by the Kingstone Trio's Tom Dooley, and celebrated in 1959 at the first Newport Folk Festival, the folk revival introduced a sense that music was meant to be more than mere entertainment. Within a few years, its boundaries had expanded dramatically. Joan Baez turned folk music into an austere form on Joan Baez 2 (? 1961 - oct 1961). Bob Gibson was one of the very early folk-singers who set to renovate the art of folk music. His best album, At The Gate Of Horn (apr 1961 - ? 1961), a live performance with Bob Camp, predates the intimate style of folk-rock by a few years. Ian (Tyson) and Sylvia (Fricker) were perhaps the most soulful, predating folk-rock with Ian's Four Strong Winds (1963) and Sylvia's You Were On My Mind (1964, the We Five's hit). Folk music evolved rapidly into something more profound and more complex, as proven by Lee Hazlewood's concept albums, Trouble Is A Lonesome Town (? 1963 - nov 1963) and The N.S.V.I.P.'s (? 1964 - ? 1964), that consist of bleak stories about misfits and losers.