A Grammatical Sketch of Berik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A PDF Combined with Pdfmergex

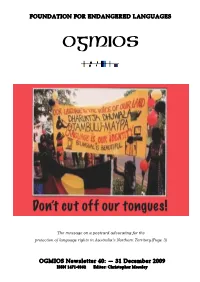

!"#$%&'("$)!"*)+$%&$,+*+%)-&$,#&,+.) ) OGMIOS The message on a postcard advocating for the protection of language rights in Australia’s Northern Territory (Page 3) ",/(".)$012304405)678)9):;)%0<0=>05)?77@) (..$);6A;B7:C?))))))+DE4F58)GH5E24FIH05)/F2030J) 2 DEBFD<'C4G"64$$4+'HI,'J'KL'=4/4M14+'NIIO' F<<C'LHPLQIKRN''''''()#$*+,'07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;' !""#"$%&$'()#$*+,'!)+#%&*'-+."/*$$' 0*&$+#1.$#&2'()#$*+",'3*24+'564&/78'9*"4:7'56;$748'<4+4&%'=>!2*"$#&*8'07+#"$*:74+'?%)@#46)8'A+%&/#"'B'?.6$8'' C#/7*6%"'D"$64+8'!&)+4%'3#$$4+' ' !"#$%&$'$()'*+,$"-'%$.' /012,3()+'14.' ' 07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;8' A*.&)%$#*&'@*+'(&)%&24+4)'X%&2.%24"8' O'S4"$)4&4'0+4"/4&$8' LPN'5%#61+**Y'X%&48'' 0%T4+"7%M'?4#27$"8' 5%$7'5!L'P!!8'(&26%&)' 34%)#&2'3EH'P?=8'(&26%&)' &*"$64+V/7#1/7%W)4M*&W/*W.Y'' /7+#"M*"464;UIV;%7**W/*M'' 'GGGW*2M#*"W*+2' The Austronesian Languages......................................... 19! LW'()#$*+#%6 3! Immersion – a film on endangered languages ............... 19! Cover Story: Northern Territory’s small languages sidelined from schools ...................................................... 3! RW'\6%/4"'$*'2*'*&'$74'S41 20! NW! =4T46*:M4&$'*@'$74'A*.&)%$#*& 4! Irish upside down............................................................ 20! Resolution of the FEL XIII Conference, Khorog, Tajikistan, OW'A*+$7/*M#&2'4T4&$" 21! 26, September, 2009 ........................................................ 4! HRELP Workshop: Endangered Languages, endangered FEL and UNESCO Atlas partnership................................ 4! knowledge & sustainability............................................. -

Comparative Vernacural Word Lists from North Coast of Irian Jaya Indonesia, 1973()

J * .U'. _J T >f T _ t W W ^ (j ‘"* ' . ff I UNIVERSIT AS INDONESIA ^ FAKULTAS SASTRA -J PERPUSTAKAAN *' I R W Z i € 3 0 J / ' ; * f a Jf{(h t-fg* U COMPARATIVE VERNACULAR WORD LISTS froia the north coast area of IRIAN JAYA, INDONESIA Tho following languages are listed: Indonesian Serui Metawedya Isirawa Sobei Kwesten ICwopke Berik ¥akde Kasimasi Keder Beneraf Betaf Yamna Kapitiauv; English The languages were recorded by members of the SUMMER INSTITUTE OP LINGUISTICS working in cooperation with UNIVBRSITAS CENDERAWASIH May, 1973 SERUI Jap on Island is locatcd between Biak Island and the north, coast of Irian Jaya. Serui Language is spoken on the southeast coast of Japen and on the islands off that coast, lhere may bo 9000 speakers of the various dialects' Of Se^tii^' Serui Language data was given by Max Wondiwoy and recorded by Joyce Sterner in December, 1972 at Jayapura, Irian Jayia* KETAWEDYA Metawedya Language is spoken on the north coast of Irian Jaya in the Apawar-Tor River areas, but the exact location and number of speakers is unknown. Mc-tawedya Language Sata was given by Betrus and recorded by James Dean in August, 1972 at Kwekwet. ISIRAWA Isirawa Language is spoken on the north ocast of Irian Jaya. Its villages extend west from Sarmi almost as far as the Apawar River. There may be 1600 speakers of Isirawa. Isirawa Language data was given h y Sebnot Scyamor and recorded by Robert Sterner in March, 1973 at Mararena village just east of Sarmi. SQB3I Sobei Language is spoken on the north coast in Sarmi, _ Bagaiserwar, and Sawar. -

LOT Dissertation Series

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/25849 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Kluge, Angela Johanna Helene Title: A grammar of Papuan Malay Issue Date: 2014-06-03 1. Introduction Papuan Malay is spoken in West Papua, which covers the western part of the island of New Guinea. This grammar describes Papuan Malay as spoken in the Sarmi area, which is located about 300 km west of Jayapura. Both towns are situated on the northeast coast of West Papua. (See Map 1 on p. xxi and Map 2 on p. xxi.) This chapter provides an introduction to Papuan Malay. The first section (§1.1) gives general background information about the language in terms of its larger geographical and linguistic settings and its speakers. In §1.2, the history of the language is summarized. The classification of Papuan Malay and its dialects are discussed in §1.3, followed in §1.4 by a description of its typological profile and in §1.5 of its sociolinguistic profile. In §1.6, previous research on Papuan Malay is summarized, followed in §1.7 by a brief overview of available materials in Papuan Malay. In §1.8 methodological aspects of the present study are described. 1.1. General information This section presents the geographical and linguistic setting of Papuan Malay and its speakers, and the area where the present research on Papuan Malay was conducted. The geographical setting is described in §1.1.1, and the linguistic setting in §1.1.2. Speaker numbers are discussed in §1.1.3, occupation details in §1.1.4, education and literacy rates in §1.1.5, and religious affiliations in §1.1.6. -

Languages of Indonesia (Papua)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Papua) Page 1 of 49 Languages of Indonesia (Papua) See language map. Indonesia (Papua). 2,220,934 (2000 census). Information mainly from C. Roesler 1972; C. L. Voorhoeve 1975; M. Donohue 1998–1999; SIL 1975–2003. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Papua) is 271. Of those, 269 are living languages and 2 are second language without mother-tongue speakers. Living languages Abinomn [bsa] 300 (1999 Clouse and Donohue). Lakes Plain area, from the mouth of the Baso River just east of Dabra at the Idenburg River to its headwaters in the Foya Mountains, Jayapura Kabupaten, Mamberamo Hulu Kecamatan. Alternate names: Avinomen, "Baso", Foya, Foja. Dialects: Close to Warembori. Classification: Language Isolate More information. Abun [kgr] 3,000 (1995 SIL). North coast and interior of central Bird's Head, north and south of Tamberau ranges. Sorong Kabupaten, Ayamaru, Sausapor, and Moraid kecamatans. About 20 villages. Alternate names: Yimbun, A Nden, Manif, Karon. Dialects: Abun Tat (Karon Pantai), Abun Ji (Madik), Abun Je. Classification: West Papuan, Bird's Head, North-Central Bird's Head, North Bird's Head More information. Aghu [ahh] 3,000 (1987 SIL). South coast area along the Digul River west of the Mandobo language, Merauke Kabupaten, Jair Kecamatan. Alternate names: Djair, Dyair. Classification: Trans-New Guinea, Main Section, Central and Western, Central and South New Guinea-Kutubuan, Central and South New Guinea, Awyu-Dumut, Awyu, Aghu More information. Airoran [air] 1,000 (1998 SIL). North coast area on the lower Apauwer River. Subu, Motobiak, Isirania and other villages, Jayapura Kabupaten, Mamberamo Hilir, and Pantai Barat kecamatans. -

NLA - Holdings on Papua

Judul Papua di - NLA - Holdings on Papua Last Update - March 11, 2004 "Irian" in the National Library of Australia What follows is a complete list of all holdings in the National Library of Australia containing the keyword "irian". The list contains - 1732 - titles in reverse chronological order * with the most recent titles listed first. A companion search for the key phrases "Netherlands New Guinea" and "Nederlands Nieuw Guinea" has also been prepared. These lists represent almost all of the material related to Papua held in the National Library. A small amount of additional material is held by the National Library that does not contain catalogued references to these keywords. This includes illustrations such as those now referenced in Papuaweb's image section (19th Century birds and 18th Century Dore Bay.) Once these lists are registered by various search engines, they will be fully searchable across the internet (unlike the NLA catalogue). This page is also searchable using the "Crtl+F" feature in Internet Explorer or similar page search features in other internet browsers. To download a printable rich text format (rtf) version of this list, please click here (1.6Mb). * Inconsistencies in the chronology of this list are related to the NLA's automated indexing system. 2004 - 1900 (with some older holdings) Author: King, Peter, 1936- ______________________________ Description: xiii, 241 p., [16] p. of plates : ill., maps, ports. ; 20 Title: West Papua and Indonesia since Suharto : independence, cm. autonomy or chaos? / Peter King. Call Number: NLq 995.1 W519 ISBN: 1903998271 Publisher: Kensington, N.S.W. : University of New South Wales Press, ______________________________ 2004. -

Online Appendix To

Online Appendix to Hammarström, Harald & Sebastian Nordhoff. (2012) The languages of Melanesia: Quantifying the level of coverage. In Nicholas Evans & Marian Klamer (eds.), Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century (Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication 5), 13-34. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ’Are’are [alu] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Southeast Solomonic, Longgu-Malaita- Makira, Malaita-Makira, Malaita, Southern Malaita Geerts, P. 1970. ’Are’are dictionary (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 14). Canberra: The Australian National University [dictionary 185 pp.] Ivens, W. G. 1931b. A Vocabulary of the Language of Marau Sound, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies VI. 963–1002 [grammar sketch] Tryon, Darrell T. & B. D. Hackman. 1983. Solomon Islands Languages: An Internal Classification (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 72). Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. Bibliography: p. 483-490 [overview, comparative, wordlist viii+490 pp.] ’Auhelawa [kud] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Western Oceanic linkage, Papuan Tip linkage, Nuclear Papuan Tip linkage, Suauic unknown, A. (2004 [1983?]). Organised phonology data: Auhelawa language [kud] milne bay province http://www.sil.org/pacific/png/abstract.asp?id=49613 1 Lithgow, David. 1987. Language change and relationships in Tubetube and adjacent languages. In Donald C. Laycock & Werner Winter (eds.), A world of language: Papers presented to Professor S. A. Wurm on his 65th birthday (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 100), 393-410. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University [overview, comparative, wordlist] Lithgow, David. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Upgs of Asia-Pacific

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & Least-Reached-UPGs of Asia-Pacific AGWM ed. Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest & Create International for permission to use their people group photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of Asia-Pacific (China = separate region & DPG) ASIA-PACIFIC SUMMARY: 3,523 total PG; 830 FR & LR-UPG = Frontier & Least Reached-Unreached People Groups Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net = August, 2020 LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. -

LCSH Section I

I(f) inhibitors I-225 (Colo.) Germany, 1947-1948 USE If inhibitors USE Interstate 225 (Colo.) Subsequent proceedings, Nuremberg War I & M Canal National Heritage Corridor (Ill.) I-244 (Tulsa, Okla.) Crime Trials, case no. 6 USE Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage USE Interstate 244 (Tulsa, Okla.) BT Nuremberg War Crime Trials, Nuremberg, Corridor (Ill.) I-255 (Ill. and Mo.) Germany, 1946-1949 I & M Canal State Trail (Ill.) USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-H-3 (Hawaii) USE Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail (Ill.) I-270 (Ill. and Mo. : Proposed) USE Interstate H-3 (Hawaii) I-5 USE Interstate 255 (Ill. and Mo.) I-hadja (African people) USE Interstate 5 I-270 (Md.) USE Kasanga (African people) I-8 (Ariz. and Calif.) USE Interstate 270 (Md.) I Ho Yüan (Beijing, China) USE Interstate 8 (Ariz. and Calif.) I-278 (N.J. and N.Y.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-10 USE Interstate 278 (N.J. and N.Y.) I Ho Yüan (Peking, China) USE Interstate 10 I-291 (Conn.) USE Yihe Yuan (Beijing, China) I-15 USE Interstate 291 (Conn.) I-hsing ware USE Interstate 15 I-394 (Minn.) USE Yixing ware I-15 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 394 (Minn.) I-K'a-wan Hsi (Taiwan) USE Polikarpov I-15 (Fighter plane) I-395 (Baltimore, Md.) USE Qijiawan River (Taiwan) I-16 (Fighter plane) USE Interstate 395 (Baltimore, Md.) I-Kiribati (May Subd Geog) USE Polikarpov I-16 (Fighter plane) I-405 (Wash.) UF Gilbertese I-17 USE Interstate 405 (Wash.) BT Ethnology—Kiribati USE Interstate 17 I-470 (Ohio and W. -

Managing Biosecurity Across Borders

Managing Biosecurity Across Borders Ian Falk • Ruth Wallace • Marthen L. Ndoen Editors Managing Biosecurity Across Borders Editors Ian Falk Ruth Wallace Charles Darwin University Charles Darwin University School of Education School of Education Ellengowan Drive Ellengowan Drive 0909 Darwin Northern Territory 0909 Darwin Northern Territory Australia Australia [email protected] [email protected] Marthen L. Ndoen Satya Wacana Christian University Economic Department and Post Graduate Development Studies Jl. Diponegoro 52–60, Salatiga 50711 Indonesia [email protected] ISBN 978-94-007-1411-3 e-ISBN 978-94-007-1412-0 DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-1412-0 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011932494 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Foreword In this era of globalization, the prefix ‘bio’ is widely used in words such asbiotech - nology, biodiversity, biosafety, biosecurity, bioimperialism, biopiracy, biodemoc- racy, biocide and bioterrorism. New terms will no doubt continue to emerge. The emergence of these ‘bio’ words is a sign of the importance of biological resources in national development and in competition between nations. Nations that can effec- tively control and manage biological resources in a sustainable manner will survive and develop in this era of globalization. -

A Grammatical Sketch of Beriki

A Grammatical Sketch of Berik IRIAN, Volume XVI, 1988 A GRAMMATICAL SKETCH OF BERIKI Peter N. Westrum2 UNCEN-SIL 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 WORDS 3.0 PHRASES 4.0 CLAUSES 5.0 SENTENCES 1 This paper was originally submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Masters of Arts Degree, Grand Forks, North Dakota. 2 Peler Westrum works under the auspices of the Cooperative Program with the Universitas Cenderawasih and the Summer Institute of Linguistics. 133 A Grammatical Sketch of Berik IRIAN, Volume XVI, 1988 IKTIDSAR Makalah ini adalah ringkasan tatabahasa bahasa Berik berdasarkan data yang dikum pulkan pengarang selama ia tinggal bersama masyarakat Berik, di Irian J aya, Indonesia. Tingkat tatabahasa yang dideskripsikan adalah: kata, frasa, klausa dan kalimat. Model tag memik digunakan sebagai model penganalisaan. Kata, unit terbatas yang tidak dapat dibagi lebih jauh ke dalam bentuk "bebas", dibagi ke dalam kelas-kelas yang dibedakan satu sarna lain menurut pola afiksasi. Frasa terdiri dad satu tagmem inti dan satu atau lebih tagmem marginal yang kata kata khas (khusus). Beberapa jenis frasa di bahas disini. KJausa, unit dari predikat, pada umumnya mememuhi inti kalimat. Terjadinya jumlah dan jenis tagmem klausa inti dengan kata kerja masing-masing menjelaskan pentransi tipan klausa yang padanya jenis-jenis klausa didasarkan. Kalimat adalah unit dasar dari wacana. Kalimat-kalimat independen, dependen, sederhana dan komplex dideskripsikan. ABSTRACT This paper is a grammatical sketch of the Berik language based on langAuge data gathered while living with the Berik people in Irian Jaya, Indonesia. The levels of the gram matical hierarchy described are words, phrases, clauses, and sentences. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Bajau, West Coast in Brunei Belait, Lakiput in Brunei Population: 12,000 Population: 1,300 World Popl: 259,000 World Popl: 1,800 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Bungku-Bajau People Cluster: Borneo-Kalimantan Main Language: Bajau, West Coast Main Language: Belait Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.02% Evangelicals: 0.15% Chr Adherents: 0.02% Chr Adherents: 0.20% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Unspecified www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations British in Brunei Brunei Malay in Brunei Population: 7,400 Population: 186,000 World Popl: 54,225,100 World Popl: 562,800 Total Countries: 128 Total Countries: 4 People Cluster: Anglo-Celt People Cluster: Malay Main Language: English Main Language: Brunei Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Islam Status: Partially reached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 8.0% Evangelicals: 0.05% Chr Adherents: 70.0% Chr Adherents: 0.06% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Translation Needed www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Southeast Asia Link - SEALINK "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Brunei Dusun, Kadazan in Brunei Population: 2,200 Population: 30,000 World Popl: