Jarník's Note of the Lecture Course Punktmengen Und Reelle Funktionen by PS Aleksandrov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

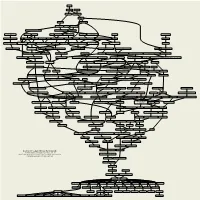

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Journal Für Die Reine Und Angewandte Mathematik

BAND 745 · DEZEMBER 2018 Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (Crelles Journal) GEGRÜNDET 1826 VON August Leopold Crelle FORTGEFÜHRT VON Carl Wilhelm Borchardt ∙ Karl Weierstrass ∙ Leopold Kronecker Lazarus Fuchs ∙ Kurt Hensel ∙ Ludwig Schlesinger ∙ Helmut Hasse Hans Rohrbach ∙ Martin Kneser ∙ Peter Roquette GEGENWÄRTIG HERAUSGEGEBEN VON Tobias H. Colding, Cambridge MA ∙ Jun-Muk Hwang, Seoul Daniel Huybrechts, Bonn ∙ Rainer Weissauer, Heidelberg Geordie Williamson, Sydney JOURNAL FÜR DIE REINE UND ANGEWANDTE MATHEMATIK (CRELLES JOURNAL) GEGRÜNDET 1826 VON August Leopold Crelle FORTGEFÜHRT VON August Leopold Crelle (1826–1855) Peter Roquette (1977–1998) Carl Wilhelm Borchardt (1857–1881) Samuel J. Patterson (1982–1994) Karl Weierstrass (1881–1888) Michael Schneider (1984–1995) Leopold Kronecker (1881–1892) Simon Donaldson (1986–2004) Lazarus Fuchs (1892–1902) Karl Rubin (1994–2001) Kurt Hensel (1903–1936) Joachim Cuntz (1994–2017) Ludwig Schlesinger (1929–1933) David Masser (1995–2004) Helmut Hasse (1929–1980) Gerhard Huisken (1995–2008) Hans Rohrbach (1952–1977) Eckart Viehweg (1996–2009) Otto Forster (1977–1984) Wulf-Dieter Geyer (1998–2001) Martin Kneser (1977–1991) Yuri I. Manin (2002–2008) Willi Jäger (1977–1994) Paul Vojta (2004–2011) Horst Leptin (1977–1995) Marc Levine (2009–2012) GEGENWÄRTIG HERAUSGEGEBEN VON Tobias H. Colding Jun-Muk Hwang Daniel Huybrechts Rainer Weissauer Geordie Williamson AUSGABEDATUM DES BANDES 745 Dezember 2018 CONTENTS O. Goertsches, D. Töben, Equivariant basic cohomology of Riemannian foliations . 1 N. A. Karpenko, A. S. Merkurjev, Motivic decomposition of compactifications of certain group varieties . 41 T. Ritter, A soft Oka principle for proper holomorphic embeddings of open Riemann surfaces into ( *)2 . 59 J. Alper, A. Isaev, Associated forms and hypersurface singularities: The binary case . -

Mathematics People

Mathematics People symmetric spaces, L²-cohomology, arithmetic groups, and MacPherson Awarded Hopf the Langlands program. The list is by far not complete, and Prize we try only to give a representative selection of his contri- bution to mathematics. He influenced a whole generation Robert MacPherson of the Institute for Advanced Study of mathematicians by giving them new tools to attack has been chosen the first winner of the Heinz Hopf Prize difficult problems and teaching them novel geometric, given by ETH Zurich for outstanding scientific work in the topological, and algebraic ways of thinking.” field of pure mathematics. MacPherson, a leading expert Robert MacPherson was born in 1944 in Lakewood, in singularities, delivered the Heinz Hopf Lectures, titled Ohio. He received his B.A. from Swarthmore College in “How Nature Tiles Space”, in October 2009. The prize also 1966 and his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1970. He carries a cash award of 30,000 Swiss francs, approximately taught at Brown University from 1970 to 1987 and at equal to US$30,000. the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1987 to The following quotation was taken from a tribute to 1994. He has been at the Institute for Advanced Study in MacPherson by Gisbert Wüstholz of ETH Zurich: “Singu- Princeton since 1994. His work has introduced radically larities can be studied in different ways using analysis, new approaches to the topology of singular spaces and or you can regard them as geometric phenomena. For the promoted investigations across a great spectrum of math- latter, their study demands a deep geometric intuition ematics. -

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

Hilbert Constance Reid

Hilbert Constance Reid Hilbert c COPERNICUS AN IMPRINT OF SPRINGER-VERLAG © 1996 Springer Science+Business Media New York Originally published by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc in 1996 All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Library ofCongress Cataloging·in-Publication Data Reid, Constance. Hilbert/Constance Reid. p. Ctn. Originally published: Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag, 1970. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-387-94674-0 ISBN 978-1-4612-0739-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4612-0739-9 I. Hilbert, David, 1862-1943. 2. Mathematicians-Germany Biography. 1. Title. QA29.HsR4 1996 SIO'.92-dc20 [B] 96-33753 Manufactured in the United States of America. Printed on acid-free paper. 9 8 7 6 543 2 1 ISBN 978-0-387-94674-0 SPIN 10524543 Questions upon Rereading Hilbert By 1965 I had written several popular books, such as From liro to Infinity and A Long Way from Euclid, in which I had attempted to explain certain easily grasped, although often quite sophisticated, mathematical ideas for readers very much like myself-interested in mathematics but essentially untrained. At this point, with almost no mathematical training and never having done any bio graphical writing, I became determined to write the life of David Hilbert, whom many considered the profoundest mathematician of the early part of the 20th century. Now, thirty years later, rereading Hilbert, certain questions come to my mind. -

Early History of the Riemann Hypothesis in Positive Characteristic

The Legacy of Bernhard Riemann c Higher Education Press After One Hundred and Fifty Years and International Press ALM 35, pp. 595–631 Beijing–Boston Early History of the Riemann Hypothesis in Positive Characteristic Frans Oort∗ , Norbert Schappacher† Abstract The classical Riemann Hypothesis RH is among the most prominent unsolved prob- lems in modern mathematics. The development of Number Theory in the 19th century spawned an arithmetic theory of polynomials over finite fields in which an analogue of the Riemann Hypothesis suggested itself. We describe the history of this topic essentially between 1920 and 1940. This includes the proof of the ana- logue of the Riemann Hyothesis for elliptic curves over a finite field, and various ideas about how to generalize this to curves of higher genus. The 1930ies were also a period of conflicting views about the right method to approach this problem. The later history, from the proof by Weil of the Riemann Hypothesis in charac- teristic p for all algebraic curves over a finite field, to the Weil conjectures, proofs by Grothendieck, Deligne and many others, as well as developments up to now are described in the second part of this diptych: [44]. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: 14G15, 11M99, 14H52. Keywords and Phrases: Riemann Hypothesis, rational points over a finite field. Contents 1 From Richard Dedekind to Emil Artin 597 2 Some formulas for zeta functions. The Riemann Hypothesis in characteristic p 600 3 F.K. Schmidt 603 ∗Department of Mathematics, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC -

Transnational Mathematics and Movements: Shiing- Shen Chern, Hua Luogeng, and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study from World War II to the Cold War1

Chinese Annals of History of Science and Technology 3 (2), 118–165 (2019) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1461.2019.02118 Transnational Mathematics and Movements: Shiing- shen Chern, Hua Luogeng, and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study from World War II to the Cold War1 Zuoyue Wang 王作跃,2 Guo Jinhai 郭金海3 (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 91768, US; Institute for the History of Natural Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China) Abstract: This paper reconstructs, based on American and Chinese primary sources, the visits of Chinese mathematicians Shiing-shen Chern 陈省身 (Chen Xingshen) and Hua Luogeng 华罗庚 (Loo-Keng Hua)4 to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in the United States in the 1940s, especially their interactions with Oswald Veblen and Hermann Weyl, two leading mathematicians at the IAS. It argues that Chern’s and Hua’s motivations and choices in regard to their transnational movements between China and the US were more nuanced and multifaceted than what is presented in existing accounts, and that socio-political factors combined with professional-personal ones to shape their decisions. The paper further uses their experiences to demonstrate the importance of transnational scientific interactions for the development of science in China, the US, and elsewhere in the twentieth century. Keywords: Shiing-shen Chern, Chen Xingshen, Hua Luogeng, Loo-Keng Hua, Institute for 1 This article was copy-edited by Charlie Zaharoff. 2 Research interests: History of science and technology in the United States, China, and transnational contexts in the twentieth century. He is currently writing a book on the history of American-educated Chinese scientists and China-US scientific relations. -

Fuchs, Lazarus

UNIVERSITATS-¨ Heidelberger Texte zur BIBLIOTHEK HEIDELBERG Mathematikgeschichte Fuchs, Lazarus (5.5.1833 – 16.4.1902) Materialsammlung, zusammengestellt von Gabriele D¨orflinger Universit¨atsbibliothek Heidelberg 2016 Homo Heidelbergensis mathematicus Die Sammlung Homo Heidelbergensis mathematicus enth¨alt Materialien zu bekannten Mathematikern mit Bezug zu Heidelberg, d.h. Mathematiker, die in Heidelberg lebten, studierten oder lehrten oder Mitglieder der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften waren. (Immanuel) Lazarus Fuchs Dozent in Heidelberg 1875–1884 Lazarus Fuchs schrieb im Jahre 1886 aus Berlin an seinen Freund Leo Koenigsberger: Ich kann Dir die Versicherung geben, daß ich noch jetzt ” fast t¨aglich mit einem gewissen Heimweh an Heidelberg zuruckdenke.¨ Wo ist die sch¨one Zeit hin, wo ich noch in der Lage war, ruhig zu arbeiten, ruhig einen Gedan- kenfaden fur¨ l¨angere Zeit abzuspinnen! Wo soll ich jetzt meine Grillen lassen, die ich sonst in alle Winde zerstreu- en konnte, wenn ich die ersten 1000 Fuß H¨ohe passirt hatte!“ Quelle: Koenigsberger, Leo: Mein Leben. — Heidelberg, 1919. — 217 S. Auszug I Anhang A 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Lexika 4 Mathematiker-Lexikon . 4 Lexikon bedeutender Mathematiker . 4 Brockhaus . 4 Deutsche biographische Enzyklop¨adie . 4 Heidelberger Gelehrtenlexikon . 5 2 Biographische Informationen 6 2.1 WWW-Biographien . 6 2.2 Fotografien . 10 2.3 Hauptstr. 23 — Fuchs’ Domizil in Heidelberg . 11 2.4 Der Mathematiker Lazarus Fuchs in Berlin . 12 2.5 Print-Biographien . 16 3 Werk 17 3.1 Digitalisierte Publikationen . 17 3.1.1 G¨ottinger Digitalisierungs-Zentrum / Beitr¨age von Lazarus Fuchs 17 3.1.2 Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften . 20 3.1.3 Heidelberger Digitale Bibliothek Mathematik . -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

The History of the Abel Prize and the Honorary Abel Prize the History of the Abel Prize

The History of the Abel Prize and the Honorary Abel Prize The History of the Abel Prize Arild Stubhaug On the bicentennial of Niels Henrik Abel’s birth in 2002, the Norwegian Govern- ment decided to establish a memorial fund of NOK 200 million. The chief purpose of the fund was to lay the financial groundwork for an annual international prize of NOK 6 million to one or more mathematicians for outstanding scientific work. The prize was awarded for the first time in 2003. That is the history in brief of the Abel Prize as we know it today. Behind this government decision to commemorate and honor the country’s great mathematician, however, lies a more than hundred year old wish and a short and intense period of activity. Volumes of Abel’s collected works were published in 1839 and 1881. The first was edited by Bernt Michael Holmboe (Abel’s teacher), the second by Sophus Lie and Ludvig Sylow. Both editions were paid for with public funds and published to honor the famous scientist. The first time that there was a discussion in a broader context about honoring Niels Henrik Abel’s memory, was at the meeting of Scan- dinavian natural scientists in Norway’s capital in 1886. These meetings of natural scientists, which were held alternately in each of the Scandinavian capitals (with the exception of the very first meeting in 1839, which took place in Gothenburg, Swe- den), were the most important fora for Scandinavian natural scientists. The meeting in 1886 in Oslo (called Christiania at the time) was the 13th in the series. -

The Intellectual Journey of Hua Loo-Keng from China to the Institute for Advanced Study: His Correspondence with Hermann Weyl

ISSN 1923-8444 [Print] Studies in Mathematical Sciences ISSN 1923-8452 [Online] Vol. 6, No. 2, 2013, pp. [71{82] www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/j.sms.1923845220130602.907 www.cscanada.org The Intellectual Journey of Hua Loo-keng from China to the Institute for Advanced Study: His Correspondence with Hermann Weyl Jean W. Richard[a],* and Abdramane Serme[a] [a] Department of Mathematics, The City University of New York (CUNY/BMCC), USA. * Corresponding author. Address: Department of Mathematics, The City University of New York (CUN- Y/BMCC), 199 Chambers Street, N-599, New York, NY 10007-1097, USA; E- Mail: [email protected] Received: February 4, 2013/ Accepted: April 9, 2013/ Published: May 31, 2013 \The scientific knowledge grows by the thinking of the individual solitary scientist and the communication of ideas from man to man Hua has been of great value in this respect to our whole group, especially to the younger members, by the stimulus which he has provided." (Hermann Weyl in a letter about Hua Loo-keng, 1948).y Abstract: This paper explores the intellectual journey of the self-taught Chinese mathematician Hua Loo-keng (1910{1985) from Southwest Associ- ated University (Kunming, Yunnan, China)z to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. The paper seeks to show how during the Sino C Japanese war, a genuine cross-continental mentorship grew between the prolific Ger- man mathematician Hermann Weyl (1885{1955) and the gifted mathemati- cian Hua Loo-keng. Their correspondence offers a profound understanding of a solidarity-building effort that can exist in the scientific community. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 51/2011 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2011/51 Emigration of Mathematicians and Transmission of Mathematics: Historical Lessons and Consequences of the Third Reich Organised by June Barrow-Green, Milton-Keynes Della Fenster, Richmond Joachim Schwermer, Wien Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, Kristiansand October 30th – November 5th, 2011 Abstract. This conference provided a focused venue to explore the intellec- tual migration of mathematicians and mathematics spurred by the Nazis and still influential today. The week of talks and discussions (both formal and informal) created a rich opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas among almost 50 mathematicians, historians of mathematics, general historians, and curators. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A60. Introduction by the Organisers The talks at this conference tended to fall into the two categories of lists of sources and historical arguments built from collections of sources. This combi- nation yielded an unexpected richness as new archival materials and new angles of investigation of those archival materials came together to forge a deeper un- derstanding of the migration of mathematicians and mathematics during the Nazi era. The idea of measurement, for example, emerged as a critical idea of the confer- ence. The conference called attention to and, in fact, relied on, the seemingly stan- dard approach to measuring emigration and immigration by counting emigrants and/or immigrants and their host or departing countries. Looking further than this numerical approach, however, the conference participants learned the value of measuring emigration/immigration via other less obvious forms of measurement. 2892 Oberwolfach Report 51/2011 Forms completed by individuals on religious beliefs and other personal attributes provided an interesting cartography of Italian society in the 1930s and early 1940s.