The History of the Abel Prize and the Honorary Abel Prize the History of the Abel Prize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differential Calculus and by Era Integral Calculus, Which Are Related by in Early Cultures in Classical Antiquity the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

History of calculus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1/1/10 5:02 PM History of calculus From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia History of science This is a sub-article to Calculus and History of mathematics. History of Calculus is part of the history of mathematics focused on limits, functions, derivatives, integrals, and infinite series. The subject, known Background historically as infinitesimal calculus, Theories/sociology constitutes a major part of modern Historiography mathematics education. It has two major Pseudoscience branches, differential calculus and By era integral calculus, which are related by In early cultures in Classical Antiquity the fundamental theorem of calculus. In the Middle Ages Calculus is the study of change, in the In the Renaissance same way that geometry is the study of Scientific Revolution shape and algebra is the study of By topic operations and their application to Natural sciences solving equations. A course in calculus Astronomy is a gateway to other, more advanced Biology courses in mathematics devoted to the Botany study of functions and limits, broadly Chemistry Ecology called mathematical analysis. Calculus Geography has widespread applications in science, Geology economics, and engineering and can Paleontology solve many problems for which algebra Physics alone is insufficient. Mathematics Algebra Calculus Combinatorics Contents Geometry Logic Statistics 1 Development of calculus Trigonometry 1.1 Integral calculus Social sciences 1.2 Differential calculus Anthropology 1.3 Mathematical analysis -

European Mathematical Society

CONTENTS EDITORIAL TEAM EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MARTIN RAUSSEN Department of Mathematical Sciences, Aalborg University Fredrik Bajers Vej 7G DK-9220 Aalborg, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS VASILE BERINDE Department of Mathematics, University of Baia Mare, Romania NEWSLETTER No. 52 e-mail: [email protected] KRZYSZTOF CIESIELSKI Mathematics Institute June 2004 Jagiellonian University Reymonta 4, 30-059 Kraków, Poland EMS Agenda ........................................................................................................... 2 e-mail: [email protected] STEEN MARKVORSEN Editorial by Ari Laptev ........................................................................................... 3 Department of Mathematics, Technical University of Denmark, Building 303 EMS Summer Schools.............................................................................................. 6 DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark EC Meeting in Helsinki ........................................................................................... 6 e-mail: [email protected] ROBIN WILSON On powers of 2 by Pawel Strzelecki ........................................................................ 7 Department of Pure Mathematics The Open University A forgotten mathematician by Robert Fokkink ..................................................... 9 Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK e-mail: [email protected] Quantum Cryptography by Nuno Crato ............................................................ 15 COPY EDITOR: KELLY -

Karen Uhlenbeck Awarded the 2019 Abel Prize

RESEARCH NEWS Karen Uhlenbeck While she was in Urbana-Champagne (Uni- versity of Illinois), Karen Uhlenbeck worked Awarded the 2019 Abel with a postdoctoral fellow, Jonathan Sacks, Prize∗ on singularities of harmonic maps on 2D sur- faces. This was the beginning of a long journey in geometric analysis. In gauge the- Rukmini Dey ory, Uhlenbeck, in her remarkable ‘removable singularity theorem’, proved the existence of smooth local solutions to Yang–Mills equa- tions. The Fields medallist Simon Donaldson was very much influenced by her work. Sem- inal results of Donaldson and Uhlenbeck–Yau (amongst others) helped in establishing gauge theory on a firm mathematical footing. Uhlen- beck’s work with Terng on integrable systems is also very influential in the field. Karen Uhlenbeck is a professor emeritus of mathematics at the University of Texas at Austin, where she holds Sid W. Richardson Foundation Chair (since 1988). She is cur- Karen Uhlenbeck (Source: Wikimedia) rently a visiting associate at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton and a visiting se- nior research scholar at Princeton University. The 2019 Abel prize for lifetime achievements She has enthused many young women to take in mathematics was awarded for the first time up mathematics and runs a mentorship pro- to a woman mathematician, Professor Karen gram for women in mathematics at Princeton. Uhlenbeck. She is famous for her work in ge- Karen loves gardening and nature hikes. Hav- ometry, analysis and gauge theory. She has ing known her personally, I found she is one of proved very important (and hard) theorems in the most kind-hearted mathematicians I have analysis and applied them to geometry and ever known. -

FIELDS MEDAL for Mathematical Efforts R

Recognizing the Real and the Potential: FIELDS MEDAL for Mathematical Efforts R Fields Medal recipients since inception Year Winners 1936 Lars Valerian Ahlfors (Harvard University) (April 18, 1907 – October 11, 1996) Jesse Douglas (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) (July 3, 1897 – September 7, 1965) 1950 Atle Selberg (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) (June 14, 1917 – August 6, 2007) 1954 Kunihiko Kodaira (Princeton University) (March 16, 1915 – July 26, 1997) 1962 John Willard Milnor (Princeton University) (born February 20, 1931) The Fields Medal 1966 Paul Joseph Cohen (Stanford University) (April 2, 1934 – March 23, 2007) Stephen Smale (University of California, Berkeley) (born July 15, 1930) is awarded 1970 Heisuke Hironaka (Harvard University) (born April 9, 1931) every four years 1974 David Bryant Mumford (Harvard University) (born June 11, 1937) 1978 Charles Louis Fefferman (Princeton University) (born April 18, 1949) on the occasion of the Daniel G. Quillen (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) (June 22, 1940 – April 30, 2011) International Congress 1982 William P. Thurston (Princeton University) (October 30, 1946 – August 21, 2012) Shing-Tung Yau (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) (born April 4, 1949) of Mathematicians 1986 Gerd Faltings (Princeton University) (born July 28, 1954) to recognize Michael Freedman (University of California, San Diego) (born April 21, 1951) 1990 Vaughan Jones (University of California, Berkeley) (born December 31, 1952) outstanding Edward Witten (Institute for Advanced Study, -

Algebraic Generality Vs Arithmetic Generality in the Controversy Between C

Algebraic generality vs arithmetic generality in the controversy between C. Jordan and L. Kronecker (1874). Frédéric Brechenmacher (1). Introduction. Throughout the whole year of 1874, Camille Jordan and Leopold Kronecker were quarrelling over two theorems. On the one hand, Jordan had stated in his 1870 Traité des substitutions et des équations algébriques a canonical form theorem for substitutions of linear groups; on the other hand, Karl Weierstrass had introduced in 1868 the elementary divisors of non singular pairs of bilinear forms (P,Q) in stating a complete set of polynomial invariants computed from the determinant |P+sQ| as a key theorem of the theory of bilinear and quadratic forms. Although they would be considered equivalent as regard to modern mathematics (2), not only had these two theorems been stated independently and for different purposes, they had also been lying within the distinct frameworks of two theories until some connections came to light in 1872-1873, breeding the 1874 quarrel and hence revealing an opposition over two practices relating to distinctive cultural features. As we will be focusing in this paper on how the 1874 controversy about Jordan’s algebraic practice of canonical reduction and Kronecker’s arithmetic practice of invariant computation sheds some light on two conflicting perspectives on polynomial generality we shall appeal to former publications which have already been dealing with some of the cultural issues highlighted by this controversy such as tacit knowledge, local ways of thinking, internal philosophies and disciplinary ideals peculiar to individuals or communities [Brechenmacher 200?a] as well as the different perceptions expressed by the two opponents of a long term history involving authors such as Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Augustin Cauchy and Charles Hermite [Brechenmacher 200?b]. -

The Wrangler3.2

Issue No. 3, Autumn 2004 Leicester The Maths Wrangler From the mathematicians at the University of Leicester http://www.math.le.ac.uk/ email: [email protected] WELCOME TO The Wrangler This is the third issue of our maths newsletter from the University of Leicester’s Department of Mathematics. You can pick it up on-line and all the back issues at our new web address http://www.math.le.ac.uk/WRANGLER. If you would like to be added to our mailing list or have suggestions, just drop us a line at [email protected], we’ll be flattered! What do we have here in this new issue? You may wonder what wallpaper and frying pans have to do with each other. We will tell you a fascinating story how they come up in new interdisciplinary research linking geometry and physics. We portrait our chancellor Sir Michael Atiyah, who recently has received the Abel prize, the maths equivalent of the Nobel prize. Sir Michael Atiyah will also open the new building of the MMC, which will be named after him, with a public maths lecture. Everyone is very welcome! More info at our new homepage http://www.math.le.ac.uk/ Contents Welcome to The Wrangler Wallpaper and Frying Pans - Linking Geometry and Physics K-Theory, Geometry and Physics - Sir Michael Atiyah gets Abel Prize The GooglePlexor The Mathematical Modelling Centre MMC The chancellor of the University of Leicester and world famous mathematician Sir Michael Atiyah (middle) receives the Abel Prize of the year 2004 together with colleague Isadore Singer (left) during the prize ceremony with King Harald of Norway. -

EVARISTE GALOIS the Long Road to Galois CHAPTER 1 Babylon

A radical life EVARISTE GALOIS The long road to Galois CHAPTER 1 Babylon How many miles to Babylon? Three score miles and ten. Can I get there by candle-light? Yes, and back again. If your heels are nimble and light, You may get there by candle-light.[ Babylon was the capital of Babylonia, an ancient kingdom occupying the area of modern Iraq. Babylonian algebra B.M. Tablet 13901-front (From: The Babylonian Quadratic Equation, by A.E. Berryman, Math. Gazette, 40 (1956), 185-192) B.M. Tablet 13901-back Time Passes . Centuries and then millennia pass. In those years empires rose and fell. The Greeks invented mathematics as we know it, and in Alexandria produced the first scientific revolution. The Roman empire forgot almost all that the Greeks had done in math and science. Germanic tribes put an end to the Roman empire, Arabic tribes invaded Europe, and the Ottoman empire began forming in the east. Time passes . Wars, and wars, and wars. Christians against Arabs. Christians against Turks. Christians against Christians. The Roman empire crumbled, the Holy Roman Germanic empire appeared. Nations as we know them today started to form. And we approach the year 1500, and the Renaissance; but I want to mention two events preceding it. Al-Khwarismi (~790-850) Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Musa Al-Khwarizmi was born during the reign of the most famous of all Caliphs of the Arabic empire with capital in Baghdad: Harun al Rashid; the one mentioned in the 1001 Nights. He wrote a book that was to become very influential Hisab al-jabr w'al-muqabala in which he studies quadratic (and linear) equations. -

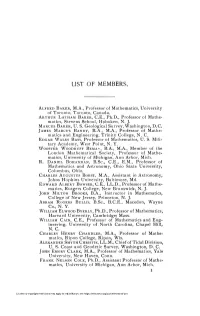

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Oslo 2004: the Abel Prize Celebrations

NEWS OsloOslo 2004:2004: TheThe AbelAbel PrizePrize celebrationscelebrations Nils Voje Johansen and Yngvar Reichelt (Oslo, Norway) On 25 March, the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters announced that the Abel Prize for 2004 was to be awarded to Sir Michael F. Atiyah of the University of Edinburgh and Isadore M. Singer of MIT. This is the second Abel Prize awarded following the Norwegian Government’s decision in 2001 to allocate NOK 200 million to the creation of the Abel Foundation, with the intention of award- ing an international prize for outstanding research in mathematics. The prize, amounting to NOK 6 million, was insti- tuted to make up for the fact that there is no Nobel Prize for mathematics. In addi- tion to awarding the international prize, the Foundation shall contribute part of its earnings to measures for increasing inter- est in, and stimulating recruitment to, Nils Voje Johansen Yngvar Reichelt mathematical and scientific fields. The first Abel Prize was awarded in machine – the brain and the computer, break those rules creatively, just like an 2003 to the French mathematician Jean- with the subtitle “Will a computer ever be artist or a musical composer. Pierre Serre for playing a key role in shap- awarded the Abel Prize?” Quentin After a brief interval, Quentin Cooper ing the modern form of many parts of Cooper, one of the BBC’s most popular invited questions from the audience and a mathematics. In 2004, the Abel radio presenters, chaired the meeting, in number of points were brought up that Committee decided that Michael F. which Sir Michael spoke for an hour to an Atiyah addressed thoroughly and profes- Atiyah and Isadore M. -

Formulation of the Group Concept Financial Mathematics and Economics, MA3343 Groups Artur Zduniak, ID: 14102797

Formulation of the Group Concept Financial Mathematics and Economics, MA3343 Groups Artur Zduniak, ID: 14102797 Fathers of Group Theory Abstract This study consists on the group concepts and the four axioms that form the structure of the group. Provided below are exam- ples to show different mathematical opera- tions within the elements and how this form Otto Holder¨ Joseph Louis Lagrange Niels Henrik Abel Evariste´ Galois Felix Klein Camille Jordan the different characteristics of the group. Furthermore, a detailed study of the formu- lation of the group theory is performed where three major areas of modern group theory are discussed:The Number theory, Permutation and algebraic equations the- ory and geometry. Carl Friedrich Gauss Leonhard Euler Ernst Christian Schering Paolo Ruffini Augustin-Louis Cauchy Arthur Cayley What are Group Formulation of the group concept A group is an algebraic structure consist- The group theory is considered as an abstraction of ideas common to three major areas: ing of different elements which still holds Number theory, Algebraic equations theory and permutations. In 1761, a Swiss math- some common features. It is also known ematician and physicist, Leonhard Euler, looked at the remainders of power of a number as a set. All the elements of a group are modulo “n”. His work is considered as an example of the breakdown of an abelian group equipped with an algebraic operation such into co-sets of a subgroup. He also worked in the formulation of the divisor of the order of the as addition or multiplication. When two el- group. In 1801, Carl Friedrich Gauss, a German mathematician took Euler’s work further ements of a group are combined under an and contributed in the formulating the theory of abelian groups. -

Transnational Mathematics and Movements: Shiing- Shen Chern, Hua Luogeng, and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study from World War II to the Cold War1

Chinese Annals of History of Science and Technology 3 (2), 118–165 (2019) doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1461.2019.02118 Transnational Mathematics and Movements: Shiing- shen Chern, Hua Luogeng, and the Princeton Institute for Advanced Study from World War II to the Cold War1 Zuoyue Wang 王作跃,2 Guo Jinhai 郭金海3 (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 91768, US; Institute for the History of Natural Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China) Abstract: This paper reconstructs, based on American and Chinese primary sources, the visits of Chinese mathematicians Shiing-shen Chern 陈省身 (Chen Xingshen) and Hua Luogeng 华罗庚 (Loo-Keng Hua)4 to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in the United States in the 1940s, especially their interactions with Oswald Veblen and Hermann Weyl, two leading mathematicians at the IAS. It argues that Chern’s and Hua’s motivations and choices in regard to their transnational movements between China and the US were more nuanced and multifaceted than what is presented in existing accounts, and that socio-political factors combined with professional-personal ones to shape their decisions. The paper further uses their experiences to demonstrate the importance of transnational scientific interactions for the development of science in China, the US, and elsewhere in the twentieth century. Keywords: Shiing-shen Chern, Chen Xingshen, Hua Luogeng, Loo-Keng Hua, Institute for 1 This article was copy-edited by Charlie Zaharoff. 2 Research interests: History of science and technology in the United States, China, and transnational contexts in the twentieth century. He is currently writing a book on the history of American-educated Chinese scientists and China-US scientific relations. -

On the Origin and Early History of Functional Analysis

U.U.D.M. Project Report 2008:1 On the origin and early history of functional analysis Jens Lindström Examensarbete i matematik, 30 hp Handledare och examinator: Sten Kaijser Januari 2008 Department of Mathematics Uppsala University Abstract In this report we will study the origins and history of functional analysis up until 1918. We begin by studying ordinary and partial differential equations in the 18th and 19th century to see why there was a need to develop the concepts of functions and limits. We will see how a general theory of infinite systems of equations and determinants by Helge von Koch were used in Ivar Fredholm’s 1900 paper on the integral equation b Z ϕ(s) = f(s) + λ K(s, t)f(t)dt (1) a which resulted in a vast study of integral equations. One of the most enthusiastic followers of Fredholm and integral equation theory was David Hilbert, and we will see how he further developed the theory of integral equations and spectral theory. The concept introduced by Fredholm to study sets of transformations, or operators, made Maurice Fr´echet realize that the focus should be shifted from particular objects to sets of objects and the algebraic properties of these sets. This led him to introduce abstract spaces and we will see how he introduced the axioms that defines them. Finally, we will investigate how the Lebesgue theory of integration were used by Frigyes Riesz who was able to connect all theory of Fredholm, Fr´echet and Lebesgue to form a general theory, and a new discipline of mathematics, now known as functional analysis.