The Last Great Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pine Warbler Is Published Monthly, September Through May, by the Piney Woods Wildlife Society, Inc

Preferences Piney Woods Wildlife Society - April Program "Kemp's Ridleys - Then and Now" by Carole Allen, Al Barr & Carlos Hernandez Ridley's Sea Turtle Don’t miss the April program presented by PWWS’ very own three sea turtle pioneers. Al Barr, Carlos Hernandez and Carole Allen will show historic photos at Rancho Nuevo, Mexico, of nesters when there were only a few hundred Kemp’s ridleys left. Their photos gave Carole the pictures she needed to talk to children and begin HEART (Help Endangered Animals-Ridley Turtles) in schools. Their stories of staying in tents on the beach with none of the comforts of home will be interesting and fun too. Be prepared to laugh! See you for sea turtles! Please join us on Wednesday, April 17, 2019. (Social time with snacks provided is at 6:30 p.m. and the meeting starts at 7 p.m. at the Big Stone Lodge at Dennis Johnston Park located at 709 Riley Fuzzel Road in Spring, Texas. Ridley Sea Turtle Eggs The Real "Leafbird" by Claire Moore Golden-fronted Leafbird in India. Photo by Mike O'Brien Here is another one of those stories that only birders will understand... We all have them! This is a picture of a real "leafbird". It's the green bird, somewhat out of focus in the center of this picture. Various Leafbird species occur in Asia... Prior to birding in Cambodia a few years ago when I saw the Golden-fronted Leafbird, I used to often say, "Never mind. It was just a LEAF bird..." Now, I can't say that anymore without thinking back to this beauty that I saw in Cambodia. -

First Record of an Extinct Marabou Stork in the Neogene of South America

First record of an extinct marabou stork in the Neogene of South America JORGE IGNACIO NORIEGA and GERARDO CLADERA Noriega, J.I. and Cladera, G. 2008. First record of an extinct marabou stork in the Neogene of South America. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53 (4): 593–600. We describe a new large species of marabou stork, Leptoptilus patagonicus (Ciconiiformes, Ciconiidae, Leptoptilini), from the late Miocene Puerto Madryn Formation, Chubut Province, Argentina. The specimen consists mainly of wing and leg bones, pelvis, sternum, cervical vertebrae, and a few fragments of the skull. We provisionally adopt the traditional system− atic scheme of ciconiid tribes. The specimen is referred to the Leptoptilini on the basis of similarities in morphology and intramembral proportions with the extant genera Ephippiorhynchus, Jabiru,andLeptoptilos. The fossil specimen resembles in overall morphology and size the species of Leptoptilos, but also exhibits several exclusive characters of the sternum, hu− merus, carpometacarpus, tibiotarsus, and pelvis. Additionally, its wing proportions differ from those of any living taxon, providing support to erect a new species. This is the first record of the tribe Leptoptilini in the Tertiary of South America. Key words: Ciconiidae, Leptoptilos, Miocene, Argentina, South America. Jorge I. Noriega [[email protected]], Laboratorio de Paleontología de Vertebrados, CICYTTP−CONICET, Matteri y España, 3105 Diamante, Argentina; Gerardo Cladera [[email protected]], Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio, Avenida Fontana 140, 9100 Trelew, Argentina. Introduction Institutional abbreviations.—BMNH, Natural History Mu− seum, London, UK; CICYTTP, Centro de Investigaciones The stork family (Ciconiidae) is a well−defined group of Científicas y Transferencia de Tecnología a la Producción, waterbirds, traditionally divided into three tribes: the Myc− Diamante, Argentina; CNAR−KB3, collections of locality 3 of teriini, the Ciconiini, and the Leptoptilini (Kahl 1971, 1972, the Kossom Bougoudi area, Centre National d’Appui à la 1979). -

Botanical Name: LEAFY PLANT

LEAFY PLANT LIST Botanical Name: Common Name: Abelia 'Edward Goucher' Glossy Pink Abelia Abutilon palmeri Indian Mallow Acacia aneura Mulga Acacia constricta White-Thorn Acacia Acacia craspedocarpa Leatherleaf Acacia Acacia farnesiana (smallii) Sweet Acacia Acacia greggii Cat-Claw Acacia Acacia redolens Desert Carpet Acacia Acacia rigidula Blackbrush Acacia Acacia salicina Willow Acacia Acacia species Fern Acacia Acacia willardiana Palo Blanco Acacia Acalpha monostachya Raspberry Fuzzies Agastache pallidaflora Giant Pale Hyssop Ageratum corymbosum Blue Butterfly Mist Ageratum houstonianum Blue Floss Flower Ageratum species Blue Ageratum Aloysia gratissima Bee Bush Aloysia wrightii Wright's Bee Bush Ambrosia deltoidea Bursage Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa Anisacanthus quadrifidus Flame Bush Anisacanthus thurberi Desert Honeysuckle Antiginon leptopus Queen's Wreath Vine Aquilegia chrysantha Golden Colmbine Aristida purpurea Purple Three Awn Grass Artemisia filifolia Sand Sage Artemisia frigida Fringed Sage Artemisia X 'Powis Castle' Powis Castle Wormwood Asclepias angustifolia Arizona Milkweed Asclepias curassavica Blood Flower Asclepias curassavica X 'Sunshine' Yellow Bloodflower Asclepias linearis Pineleaf Milkweed Asclepias subulata Desert Milkweed Asclepias tuberosa Butterfly Weed Atriplex canescens Four Wing Saltbush Atriplex lentiformis Quailbush Baileya multiradiata Desert Marigold Bauhinia lunarioides Orchid Tree Berlandiera lyrata Chocolate Flower Bignonia capreolata Crossvine Bougainvillea Sp. Bougainvillea Bouteloua gracilis -

Valley Native Plants for Birds

Quinta Mazatlan WBC 1/19/17 SB 1 TOP VALLEY NATIVE FRUITING PLANTS FOR BIRDS TALL TREES, 30 FT OR GREATER: Common Name Botanical Name Height Width Full Shade/ Full Evergreen Bloom Bloom Fruit Notes (ft) (ft) Sun Sun Shade Color Period Color Anacua, Ehretia anacua 20-50 40-60 X X X White Summer- Yellow- Leaves feel like sandpaper; Sandpaper Tree, Fall Orange fragrant flowers. Mature trunk has Sugarberry characteristic outgrowth which resembles cylinders put together to form it. Edible fruit. Butterfly nectar plant. Sugar Hackberry, Celtis laevigata 30-50 50 X X X Greenish, Spring Red Fast-growing, short-lived tree, with Palo Blanco tiny an ornamental grey, warty bark. Shallow rooted and prone to fungus; should be planted away from structures. Caterpillar host plant. SMALL TREES (LESS THAN 30 FT): Common Name Botanical Name Height Width Full Shade/ Full Evergreen Bloom Bloom Fruit Notes (ft) (ft) Sun Sun Shade Color Period Color Brasil, Condalia hookeri 12-15 15 X X X Greenish- Spring- Black Branches end in thorns; shiny Capul Negro, yellow, Summer leaves. Capulín, Bluewood small Condalia Coma, Sideroxylon 15-30 15 X X X White Summer- Blue- Very fragrant flowers; sticky, edible Chicle, celastrinum Fall, after black fruit; thorny; glossy leaves. Saffron Plum rain Granjeno, Celtis pallida 10-20 12 X X X X Greenish, Spring Orange Edible fruit; spiny; bark is mottled Spiny tiny grey. Can be small tree or shrub. Hackberry Texas Diospyros 15-30 15 X X X X White Spring Black Mottled, peeling ornamental bark; Persimmon, texana great native choice instead of the Chapote Crape Myrtle. -

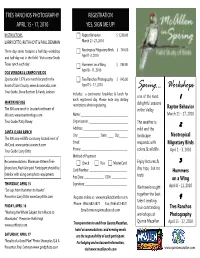

Spring... Workshops Tour Guide: Steve Bentsen & Hardy Jackson Includes a Continental Breakfast & Lunch for One of the Most Each Registered Day

TRES RANCHOS PHOTOGRAPHY REGISTRATION APRIL 15 - 17, 2010 YES, SIGN ME UP! INSTRUCTORS Raptor Behavior $ 1,200.00 LARRY DITTO, RUTH HOYT & PAUL DENMAN March 21- 27, 2010 Three day series features a half-day workshop Neotropical Migratory Birds $ 749.00 April 1-3, 2010 and half-day out in the field. Visit a new South Texas ranch each day . Hummers on a Wing $ 749.00 April 8 - 11, 2010 DOS VENADAS & CAMPOS VIEJOS Spectacular 1,370 acre ranch located in the Tres Ranchos Photography $ 945.00 heart of Starr County. www.dosvenadas.com. April 15 - 17, 2010 Spring... Workshops Tour Guide: Steve Bentsen & Hardy Jackson Includes a continental breakfast & lunch for one of the most each registered day. Please note any dietary 1 MARTIN REFUGE delightful seasons restrictions when registering. Raptor Behavior The 300 acre ranch is located northwest of in the Valley. Name: __________________________________ March 21 - 27, 2010 Mission. www.martinrefuge.com Tour Guide: Patty Raney Organization: ____________________________ The weather is Address: ________________________________ mild and the 2 SANTA CLARA RANCH City: _______________ State: ____ Zip:______ landscape Neotropical The 300 acre wildlife sanctuary located west of Email: __________________________________ McCook. www.santaclararanch.com responds with Migratory Birds Tour Guide: Larry Ditto Phone: _________________________________ colors & wildlife. April 1 - 3, 2010 Method of Payment Recommendations: Minimum 400mm Tele- Check Visa MasterCard Enjoy lectures & 3 photo lens, flash & tripod. Participant -

December 2012 Number 1

Calochortiana December 2012 Number 1 December 2012 Number 1 CONTENTS Proceedings of the Fifth South- western Rare and Endangered Plant Conference Calochortiana, a new publication of the Utah Native Plant Society . 3 The Fifth Southwestern Rare and En- dangered Plant Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, March 2009 . 3 Abstracts of presentations and posters not submitted for the proceedings . 4 Southwestern cienegas: Rare habitats for endangered wetland plants. Robert Sivinski . 17 A new look at ranking plant rarity for conservation purposes, with an em- phasis on the flora of the American Southwest. John R. Spence . 25 The contribution of Cedar Breaks Na- tional Monument to the conservation of vascular plant diversity in Utah. Walter Fertig and Douglas N. Rey- nolds . 35 Studying the seed bank dynamics of rare plants. Susan Meyer . 46 East meets west: Rare desert Alliums in Arizona. John L. Anderson . 56 Calochortus nuttallii (Sego lily), Spatial patterns of endemic plant spe- state flower of Utah. By Kaye cies of the Colorado Plateau. Crystal Thorne. Krause . 63 Continued on page 2 Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights Reserved. Utah Native Plant Society Utah Native Plant Society, PO Box 520041, Salt Lake Copyright 2012 Utah Native Plant Society. All Rights City, Utah, 84152-0041. www.unps.org Reserved. Calochortiana is a publication of the Utah Native Plant Society, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organi- Editor: Walter Fertig ([email protected]), zation dedicated to conserving and promoting steward- Editorial Committee: Walter Fertig, Mindy Wheeler, ship of our native plants. Leila Shultz, and Susan Meyer CONTENTS, continued Biogeography of rare plants of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. -

Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO BOTANY 0 NCTMBER 52 Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae Harold Robinson, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, andJames F. Weedin SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1981 ABSTRACT Robinson, Harold, A. Michael Powell, Robert M. King, and James F. Weedin. Chromosome Numbers in Compositae, XII: Heliantheae. Smithsonian Contri- butions to Botany, number 52, 28 pages, 3 tables, 1981.-Chromosome reports are provided for 145 populations, including first reports for 33 species and three genera, Garcilassa, Riencourtia, and Helianthopsis. Chromosome numbers are arranged according to Robinson’s recently broadened concept of the Heliantheae, with citations for 212 of the ca. 265 genera and 32 of the 35 subtribes. Diverse elements, including the Ambrosieae, typical Heliantheae, most Helenieae, the Tegeteae, and genera such as Arnica from the Senecioneae, are seen to share a specialized cytological history involving polyploid ancestry. The authors disagree with one another regarding the point at which such polyploidy occurred and on whether subtribes lacking higher numbers, such as the Galinsoginae, share the polyploid ancestry. Numerous examples of aneuploid decrease, secondary polyploidy, and some secondary aneuploid decreases are cited. The Marshalliinae are considered remote from other subtribes and close to the Inuleae. Evidence from related tribes favors an ultimate base of X = 10 for the Heliantheae and at least the subfamily As teroideae. OFFICIALPUBLICATION DATE is handstamped in a limited number of initial copies and is recorded in the Institution’s annual report, Smithsonian Year. SERIESCOVER DESIGN: Leaf clearing from the katsura tree Cercidiphyllumjaponicum Siebold and Zuccarini. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Chromosome numbers in Compositae, XII. -

Coastal Plains Region the Coastal Plains Region Includes About One-Third of Texas

TXSE_1_03_p046-067 11/21/02 4:29 PM Page 52 Identifying the Why It Matters Now 2 The landforms, waterways, trees, and plants give each subregion Four Regions of Texas its unique character. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA subregion, Coastal Plains 1. Identify the location of each natural As you learned in Chapter 1, Texas region, escarpment, growing subregion of Texas. can be divided into four regions. season, North Central 2. Compare the regions and subregions Now you will see how the lands Plains region, steppe, Great of Texas. within each region can be further Plains region, aquifer, divided. By analyzing similarities Mountains and Basins and differences, we can further region classify Texas into 11 subregions. WHAT Would You Do? Imagine that you are a member of the Texas Film Commission. Your Write your response job is to persuade moviemakers to shoot their films in Texas. To do to Interact with History this, you must be able to direct them to a location that matches the in your Texas Notebook. setting of their story. Where in Texas might you send a film crew to shoot a horror movie about a mysterious forest creature? What if the movie were about rock climbers? What if it were about being stranded on an uninhabited planet? Explain your reasoning. Dividing Up Texas Natural regions are determined by physical geography features such as landforms, climate, and vegetation. Texas can be divided into four large natural regions: the Coastal Plains, North Central Plains, Great Plains, and Mountains and Basins regions. The first three natural regions subregion a smaller division can also be divided into smaller subregions. -

A Tale of Two Cacti –The Complex Relationship Between Peyote (Lophophora Williamsii) and Endangered Star Cactus (Astrophytum Asterias)

A Tale of Two Cacti –The Complex Relationship between Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and Endangered Star Cactus (Astrophytum asterias). 1 2 2 TERRY, M. , D. PRICE , AND J. POOLE. 1Sul Ross State University, Department of Biology, Alpine, Texas 79832. 2Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Wildlife Diversity Branch, 3000 S. IH-35, Suite 100, Austin, Texas 78704. ABSTRACT Astrophytum asterias, commonly called star cactus, is a federally listed endangered cactus endemic to the Tamaulipan thornscrub ecoregion of extreme southern Texas, USA, and Tamaulipas and Nuevo Leon, Mexico. Only three metapopulations totaling less than 4000 plants are presently known in Texas. Star cactus, known locally as “star peyote”, is highly sought by collectors. This small, dome-shaped, spineless, eight- ribbed cactus is sometimes mistaken for peyote (Lophophora williamsii), which grows in the same or adjacent habitats. Peyote is harvested from native thornscrub habitats in Texas by local Hispanic people and sold to peyoteros, licensed distributors who sell the peyote to Native American Church members. Annual peyote harvests in Texas approach 2,000,000 “buttons” (crowns). Although the peyoteros do not buy star cactus from harvesters, they cultivate star cactus in peyote gardens at their places of business and give star cacti to their customers as lagniappe. If even 0.1% of harvested “peyote” is actually star cactus, the annual take of this endangered cactus approaches the total number of wild specimens known in the U.S. This real but unquantifiable take, together with information from interviews with local residents, suggests the existence of many more star cactus populations than have been documented. ASTROPHYTUM AND LOPHOPHORA – Poole 1990). -

INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a Synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a Historical Sketch

ZOOLOGÍA-TAXONOMÍA www.unal.edu.co/icn/publicaciones/caldasia.htm Caldasia 31(2):407-440. 2009 HACIA UNA SÍNTESIS DE LOS PAPILIONOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a historical sketch JOSÉ LUIS SALINAS-GUTIÉRREZ El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] CLAUDIO MÉNDEZ Escuela de Biología, Universidad de San Carlos, Ciudad Universitaria, Campus Central USAC, Zona 12. Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] MERCEDES BARRIOS Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (CECON), Universidad de San Carlos, Avenida La Reforma 0-53, Zona 10, Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] CARMEN POZO El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] JORGE LLORENTE-BOUSQUETS Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Apartado Postal 70-399, México D.F. 04510; México. [email protected]. Autor responsable. RESUMEN La riqueza biológica de Mesoamérica es enorme. Dentro de esta gran área geográfi ca se encuentran algunos de los ecosistemas más diversos del planeta (selvas tropicales), así como varios de los principales centros de endemismo en el mundo (bosques nublados). Países como Guatemala, en esta gran área biogeográfi ca, tiene grandes zonas de bosque húmedo tropical y bosque mesófi lo, por esta razón es muy importante para analizar la diversidad en la región. Lamentablemente, la fauna de mariposas de Guatemala es poco conocida y por lo tanto, es necesario llevar a cabo un estudio y análisis de la composición y la diversidad de las mariposas (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) en Guatemala. -

Descriptions of Male and Female Genitalia of Kricognia Lyside (Lepidoptera: Pieridae: Coliadinae)

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository Descriptions of Male and Female Genitalia of Kricognia lyside (Lepidoptera: Pieridae: Coliadinae) Yamauchi, Takeo Setouchi Field Science Center, Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima Uniersity Yata, Osamu Biosystematics Laboratory, Faculty of Social and Cultural Studies, Kyushu University http://hdl.handle.net/2324/2697 出版情報:ESAKIA. 44, pp.217-224, 2004-03-31. 九州大学大学院農学研究院昆虫学教室 バージョン: 権利関係: ESAKIA, (44): 217-224. March 10, 2004 Descriptions of Male and Female Genitalia of Kricogonia lyside (Lepidoptera: Pieridae: CoIIadinae) Takeo Yamauchi Setouchi Field Science Center, Graduate School of Biosphere Science, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima, 739-8528 Japan and OsamuYata Biosystematics Laboratory, Faculty of Social and Cultural Studies, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, 8 10-8560 Japan Abstract. The male and female genitalia of Kricogonia lyside (Godart, 18 19), the type species of the genus Kricogonia Reakirt, 1863, are described and figured in detail, which is for the first time for female. The unique character states of female genitalia newly found in the family Pieridae are discussed. Key words: Kricogonia lyside, Coliadinae, Pieridae, male genitalia, female genitalia, description. Introduction The genus Kricogonia Reakirt, 1863 belonging to the sub family Coliadinae (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) is distributed from the southern United States to Venezuela, Cuba and the Antilles (Smith et al., 1994). According to Smith et al. (1994), two species are recognized from these areas: Kricogonia lyside (Godart, 1819), the type species of Kricogonia, and Kricogonia cabrerai Ramsden, 1920. Klots (1933) published an excellent generic revision of the family Pieridae in which he illustrated and described the male genitalia of K. lyside, but the relationship of Kricogonia to other pierid genera was not clearly shown. -

Texas Big Tree Registry a List of the Largest Trees in Texas Sponsored by Texas a & M Forest Service

Texas Big Tree Registry A list of the largest trees in Texas Sponsored by Texas A & M Forest Service Native and Naturalized Species of Texas: 320 ( D indicates species naturalized to Texas) Common Name (also known as) Latin Name Remarks Cir. Threshold acacia, Berlandier (guajillo) Senegalia berlandieri Considered a shrub by B. Simpson 18'' or 1.5 ' acacia, blackbrush Vachellia rigidula Considered a shrub by Simpson 12'' or 1.0 ' acacia, Gregg (catclaw acacia, Gregg catclaw) Senegalia greggii var. greggii Was named A. greggii 55'' or 4.6 ' acacia, Roemer (roundflower catclaw) Senegalia roemeriana 18'' or 1.5 ' acacia, sweet (huisache) Vachellia farnesiana 100'' or 8.3 ' acacia, twisted (huisachillo) Vachellia bravoensis Was named 'A. tortuosa' 9'' or 0.8 ' acacia, Wright (Wright catclaw) Senegalia greggii var. wrightii Was named 'A. wrightii' 70'' or 5.8 ' D ailanthus (tree-of-heaven) Ailanthus altissima 120'' or 10.0 ' alder, hazel Alnus serrulata 18'' or 1.5 ' allthorn (crown-of-thorns) Koeberlinia spinosa Considered a shrub by Simpson 18'' or 1.5 ' anacahuita (anacahuite, Mexican olive) Cordia boissieri 60'' or 5.0 ' anacua (anaqua, knockaway) Ehretia anacua 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, Carolina Fraxinus caroliniana 90'' or 7.5 ' ash, Chihuahuan Fraxinus papillosa 12'' or 1.0 ' ash, fragrant Fraxinus cuspidata 18'' or 1.5 ' ash, green Fraxinus pennsylvanica 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, Gregg (littleleaf ash) Fraxinus greggii 12'' or 1.0 ' ash, Mexican (Berlandier ash) Fraxinus berlandieriana Was named 'F. berlandierana' 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, Texas Fraxinus texensis 60'' or 5.0 ' ash, velvet (Arizona ash) Fraxinus velutina 120'' or 10.0 ' ash, white Fraxinus americana 100'' or 8.3 ' aspen, quaking Populus tremuloides 25'' or 2.1 ' baccharis, eastern (groundseltree) Baccharis halimifolia Considered a shrub by Simpson 12'' or 1.0 ' baldcypress (bald cypress) Taxodium distichum Was named 'T.