Blairism and the Countryside: the Legacy of Modernisation in Rural Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

The Journal of William Morris Studies

The Journal of William Morris Studies volume xx, number 3, winter 2013 Editorial – Fears and Hopes Patrick O’Sullivan 3 William Morris and Robert Browning Peter Faulkner 13 Two Williams of one medieval mind: reading the Socialist William Morris through the lens of the Radical William Cobbett David A. Kopp 31 Making daily life ‘as useful and beautiful as possible’: Georgiana Burne-Jones and Rottingdean, 1880–1904 Stephen Williams 47 William Morris: An Annotated Bibliography 2010–2011 David and Sheila Latham 66 Reviews. Edited by Peter Faulkner Michael Rosen, ed, William Morris, Poems of Protest (David Goodway) 99 Ingrid Hanson, William Morris and the Uses of Violence, 1856–1890 (Tony Pinkney) 103 The Journal of Stained Glass, vol. XXXV, 2011, Burne-Jones Special Issue. (Peter Faulkner) 106 the journal of william morris studies . winter 2013 Rosie Miles, Victorian Poetry in Context (Peter Faulkner) 110 Talia SchaVer, Novel Craft (Phillippa Bennett) 112 Glen Adamson, The Invention of Craft (Jim Cheshire) 115 Alec Hamilton, Charles Spooner (1862–1938) Arts and Crafts Architect (John Purkis) 119 Clive Aslet, The Arts and Crafts Country House: from the archives of Country Life (John Purkis) 121 Amy Woodhouse-Boulton, Transformative Beauty. Art Museums in Industrial Britain; Katherine Haskins, The Art Journal and Fine Art Publishing in Vic- torian England, 1850–1880 (Peter Faulkner) 124 Jonathan Meades, Museum without walls (Martin Stott) 129 Erratum 133 Notes on Contributors 134 Guidelines for Contributors 136 issn: 1756–1353 Editor: Patrick O’Sullivan ([email protected]) Reviews Editor: Peter Faulkner ([email protected]) Designed by David Gorman ([email protected]) Printed by the Short Run Press, Exeter, UK (http://www.shortrunpress.co.uk/) All material printed (except where otherwise stated) copyright the William Morris Society. -

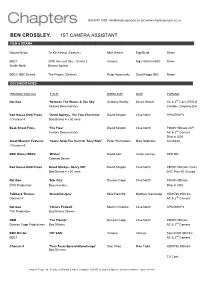

Ben Crossley. 1St Camera Assistant

020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk ! 020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk ! BEN CROSSLEY. 1ST CAMERA ASSISTANT FILM & DRAMA Natural Nylon ‘To Kill A King’ (Feature) Mike Barker Eigil Bryld 35mm BBC1 ‘2000 Acres of Sky’ - Series 2 Various Nigel Walters BSC 16mm Zenith North (Drama Series) BBC1/ BBC Drama ‘The Project’ (Drama) Peter Kosminsky David Higgs BSC 16mm DOCUMENTARIES PRODUCTION CO. TITLE DIRECTOR DOP FORMAT Nat Geo ‘Between The Waves & The Sky’ Anthony Wonke Simon Niblett AC & 2nd Cam, RED MX, Feature Documentary Cineflex. Ongoing-Qata Red House DOX Prods ‘David Starkys- The Two Churchills’ David Sington Clive North HPX3700 P2 / Channel 4 Doc/Drama 4 x 50 mins Beak Street Films ‘The Flaw’ David Sington Clive North F900R HDCam 24P Feature Documentary AC & 2nd Camera Shot in USA Great Western Features ‘Comic Strip-The Hunt for Tony Blair’ Peter Richardson Mike Robinson Arri Alexa / Channel 4 BBC Wales/ BBC2 ‘Whites’ David Kerr Jamie Cairney RED MX Comedy Series Red House DOX Prods David Starkys- Henry VIII' David Sington Clive North F900R HDCam/ Varicam Doc/Drama 4 x 50 mins DVC Pro HD. Europe Nat Geo ‘Star City’ Duncan Copp Clive North F900R HDCam DOX Production Documentary Shot in USA Talkback Thames ‘Grand Designs’ Mike Ratcliffe Matthew Gammage HDW790 HDCam Channel 4 AC & 2nd Camera Nat Geo ‘Christs Fireball’ Martin O’Collins Clive North HPX3700 P2 TV6 Production Doc/Drama 50mins HBO ‘The Planets’ Duncan Copp Clive North F900R HDCam Duncan Copp Productions Doc 50mins AC & 2nd Camera BBC Bristol ‘DIY SOS’ Various Various Sony F800 XDCam BBC1 AC & 2nd Camera Channel 4 ‘Time Team Special-Stonehenge’ Sian Price Mike Todd HDW790 HDCam Doc 50 mins CV Cont…… Chapters People Ltd. -

Ugly Rumours: a Mockumentary Beyond the Simulated Reality

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 4, Issue 11, 2017, PP 22-29 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) Ugly Rumours: A Mockumentary beyond the Simulated Reality Kağan Kaya Faculty of Letters English Language and Literature, Cumhuriyet University, Turkey *Corresponding Author: Kağan Kaya, Faculty of Letters English Language and Literature, Cumhuriyet University, Turkey ABSTRACT Ugly Rumours was the name of a rock band which was co-founded by Tony Blair when he was a student at St John's College, Oxford. In the hands of two British dramatists, Howard Brenton and Tariq Ali, it transformed into a name of the satirical play against New Labour at the end of the last century. The play encapsulates the popular political struggle of former British leaders, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. However, this work aims at analysing some sociological messages of the play in which Brenton and Ali tell on media and reality in the frame of British politics and democracy. Through the analyses of this unfocussed local mock-epic, it precisely points out ideas reflecting the real which is manipulated for the sake of power in a democratic atmosphere. Thereof it takes some views on Simulation Theory of French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard as the basement of analyses. According to Baudrillard, our perception of things has become corrupted by a perception of reality that never existed. He believes that everything changes with the device of simulation. Hyper-reality puts an end to the real as referential by exalting it as model. (Baudrillard, 1983:21, 85) That is why, establishing a close relationship with the play, this work digs deeper into the play through the ‘Simulation Theory’ and analysing characters who are behind the unreal, tries to display the role of Brenton and Ali’s drama behind the fact. -

Blair's Political Reforms and the Question of Governance

The People‟s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Mentouri University, Constantine Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Blair’s Political Reforms and the Question of Governance A dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment for the Degree of Master in British and American studies By BENMECHERI Amina Supervised by: Pr. HAROUNI Brahim June 2010 1 CONTENTS Dedication………………………………………………………………………………..i Acknowledgement……………………………………………………………………….ii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….iii Introduction………………………………………………………………...……………vi INTRODUCTION CHAPTER ONE: Tony Blair and the New Labour Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……….1 1- A new style in politics……………………………………………………….………2 1.1-Prime Minister in power……………………………………………………………..4 1.2-The win of the Labour Party in the 1997 election……………………………………5 1.3-Blair‟s strategy……………………………………………………..………………6 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………..9 Endnotes…………………………………………………………………………………10 CHAPTER TWO: The Third Way Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..12 1-Modernising social democracy……………………………………….……………..13 1.1-Constructing the Third Way…………………………………………………13 1.2-Modernisation: putting the “New” into New Labour……………………….15 1.3-Modernising Governance……………………………………………………17 Conclusion………………………………………………………………..……………..21 Endnotes…………………………………………………………………..……………..22 CHAPTER THREE: Modernising Government Introduction………………………………………………………………..……………23 1-The politics of reforms…………………………………………….…………………24 -

After the New Social Democracy Offers a Distinctive Contribution to Political Ideas

fitzpatrick cvr 8/8/03 11:10 AM Page 1 Social democracy has made a political comeback in recent years, After thenewsocialdemocracy especially under the influence of the Third Way. However, not everyone is convinced that this ‘new social democracy’ is the best means of reviving the Left’s social project. This book explains why and offers an alternative approach. Bringing together a range of social and political theories After the After the new new social democracy engages with some of the most important contemporary debates regarding the present direction and future of the Left. Drawing upon egalitarian, feminist and environmental social democracy ideas it proposes that the social democratic tradition can be renewed but only if the dominance of conservative ideas is challenged more effectively. It explores a number of issues with this aim in mind, including justice, the state, democracy, welfare reform, new technologies, future generations and the new genetics. Employing a lively and authoritative style After the new social democracy offers a distinctive contribution to political ideas. It will appeal to all of those interested in politics, philosophy, social policy and social studies. Social welfare for the Tony Fitzpatrick is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Sociology and Social twenty-first century Policy, University of Nottingham. FITZPATRICK TONY FITZPATRICK TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page i After the new social democracy TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page ii For my parents TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page iii After the new social democracy Social welfare for the twenty-first century TONY FITZPATRICK Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave TZPPR 4/25/2005 4:45 PM Page iv Copyright © Tony Fitzpatrick 2003 The right of Tony Fitzpatrick to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

In Churchill's Footsteps: How Blair Bombed Out

BRITISH POLITICAL LEADERSHIP FROM CHURCHILL TO BLAIR: In Churchill's Footsteps: How Blair Bombed Out MICHAEL DOBBS There is an old-fashioned view that a debate should attempt to have a beginning, a middle, and an end-and preferably in that order. I find that view both appealing and relevant since I have a strong suspicion that, no matter how hard we try to avoid it, the final resting place of our discussion today is preor- dained. That place is Iraq. But before we disappear into the mists and mirages of the deserts around Baghdad, let us begin by bending our knee to the formal sub- ject of this debate, which is the quality of leadership. First, we need a definition. What is political leadership? It's not the same as simply being a leader, a matter of occupying office. Ten men and one woman have sat in that famous chair before the fireplace in 10 Downing Street since the time of Churchill, yet today the majority of them lie buried in unmarked graves. Their greatest political success often is their arrival at Downing Street; most of them have left with heads low and sometimes in tears, their reputations either greatly diminished or in tatters. Furthermore, the quality of leadership should not be confused with the ability to win elections or to cling to office. Harold Wilson won three elections during this period, but was not great, while John Major sur- vived for seven years, leaving most people to wonder how. So let me offer a starting point for the discussion by suggesting that polit- ical leadership is about change and movement. -

Blair's Britain

Blair’s Britain: the social & cultural legacy Social and cultural trends in Britain 1997-2007 and what they mean for the future the social & cultural legacy Ben Marshall, Bobby Duffy, Julian Thompson, Sarah Castell and Suzanne Hall Blair’s Britain: 1 Blair’s Britain: the social & cultural legacy Social and cultural trends in Britain 1997-2007 and what they mean for the future Ben Marshall, Bobby Duffy, Julian Thompson, Sarah Castell and Suzanne Hall 2. The making of Blair’s Britain Contents Foreword 2 Summary 3 1. Introduction 8 Ipsos MORI’s evidence base 8 From data to insight 9 2. The making of Blair’s Britain 12 Before Blair 12 Blair, Labour and Britain 13 Brown takes over 15 3. Blair’s Britain, 1997-2007 18 Wealth, inequality and consumerism 18 Ethical consumerism, well-being and health 24 Public priorities, public services 31 People, communities and places 36 Crime, security and identity 43 ‘Spin’ and the trust deficit 48 Technology and media 51 Sport, celebrity and other pastimes 54 Summary: Britain then and now 56 4. Brown’s Britain: now and next 60 From understanding to action 60 Describing culture through opposites 60 Mapping oppositions 65 Summary: what next? 70 Endnotes 72 the social & cultural legacy Blair’s Britain: Foreword There are many voices and perspectives in Britain at the end of the Blair era. Some of these say the British glass is half full, others that it is half empty. Take the National Health Service as an example. By almost every indicator, ask any expert, there is no doubt things are very much better. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

Politicization and European Integration Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks

Crouch & Streeck Part 3 24/4/06 1:48 pm Page 205 8. The neo-functionalists were (almost) right: politicization and European integration Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks In a recent paper, Philippe Schmitter laments that ‘no theory of regional inte- gration has been as misunderstood, caricatured, pilloried, proven wrong and rejected as often as neo-functionalism’ (2002, p. 1). And he goes on to expli- cate, embrace and elaborate neo-functionalism in his inimitable way. Almost 50 years of neo-functionalism have taught us a thing or two about regional integration. Neo-functionalism identifies basic building blocks for any valid theory of the subject and, more generally, for any valid theory of jurisdictional architecture. Neo-functionalism argues that regional integration is shaped by its func- tional consequences – the Pareto gains accruing to integration – but that func- tional needs alone cannot explain integration. Regional integration gives rise to potent political tensions. It shakes up relative capabilities, creates new inequalities, and transforms preferences. Above all, it leads to politicization, a general term for the process by which the political conflicts unleashed by inte- gration come back to shape it. Neo-functionalists recognize that a decisive limitation of functionalism is that it does not engage the political conse- quences of its own potential success. What happens when the ‘objects’ of regional integration – citizens and political parties – wake up and became its arbiters? In this essay, we begin by taking a close look at how neo-functionalism and its precursor, functionalism, conceive the politics of regional integration. Then we turn to the evidence of the past two decades and ask how politicization has shaped the level, scope and character of European integration. -

Socialism 1111

Chap 11 6/5/03 3:13 pm Page 214 Socialism 1111 Here we explore socialism – an ideology that, uniquely, sprang from the industrial revolution and the experience of the class that was its product, the working class. Though a more coherent ideology than conservatism, socialism has several markedly different strands. In order to appreciate these, and the roots of socialism in a concrete historical experience, we explore its origins and devel- opment in the last two centuries in some depth, giving particular attention to the British Labour Party. We conclude with some reflections on ‘Blairism’ and the ‘Third Way’, and the possible future of socialism as an ideology. POINTS TO CONSIDER ➤ Does the assertion that socialism is the product of specific historical circumstances cast doubt on its claims to universal validity? ➤ Is utopian socialism mere daydreaming? ➤ Which is the more important of socialism’s claims: justice or efficiency? ➤ Does common ownership equate with state ownership? ➤ Do socialists mean more by equality than liberals do? ➤ Is socialism in Britain simply what the Labour Party does? ➤ Is there a future for socialism? Kevin Harrison and Tony Boyd - 9781526137951 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/27/2021 10:51:13AM via free access Chap 11 6/5/03 3:13 pm Page 215 Socialism 215 The general diffusion of manufacturers throughout a country generates a new character in its inhabitants; and as this character is formed upon a principle quite unfavourable to individual or general happiness, it will produce the most lamen- table and permanent evils, unless the tendency be counteracted by legislative interference and direction. -

The US Republicans: Lessons for the Conservatives?

2 Edward Ashbee The US Republicans The US Republicans: lessons for the Conservatives? Edward Ashbee Both Labour’s victory in the 1997 general election and the US Republicans’ loss of the White House in 1992 led to crises of confidence among conser- vatives. Although there were those in both countries who attributed these defeats to presentational errors or the campaigning skills of their Labour and Democrat opponents, others saw a need for far-reaching policy shifts and a restructuring of conservative politics. This chapter considers the character of US conservatism during the 1990s, the different strands of opinion that emerged in the wake of the 1992 defeat, the factors that shaped the victorious Bush campaign in 2000, and the implications of these events for the Conser- vative Party in Britain. George Bush’s 1992 defeat was a watershed, bringing twelve years of Republican rule in the White House to a close. Although constrained by Democratic opposition in Congress, the ‘Reagan revolution’ had, seemingly, ushered in a fundamental shift in the character of US politics. Tax rates had been reduced and there was growing confidence in US economic capabilities. Indeed, Reaganism appropriated a number of the long-term goals that had long been associated with liberalism. In particular, the supply-side policies with which the administration associated itself promised that unfettered mar- ket forces would not only increase overall economic growth but also alleviate poverty and address deprivation in the inner-city neighbourhoods. The USA had also, it was said, regained its place in the world through the arms build-up and military intervention in Grenada.