The Journal of William Morris Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'William Morris

B .-e~ -. : P R I C E T E N CENTS THE NEW ORDER SERIES: NUMBER ONE ‘William Morris CRAFTSMAN, WRITER AND SOCIAL RBFORM~R BP OSCAR LOVELL T :R I G G S PUBLISHED BY THE OSCAR L. TRIGGS PUBLISHING COMPANY, S58 DEARBORN STREET, CHICAGO, ILL. TRADE SUPPLIED BY THE WESTERN NRWS COMIPANY, CHICAGO TEN TEN LARGE VOLUMES The LARGE VOLUMES Library dl University Research RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY SOCIOLOGY, SCIENCE HISTORY IN ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS The Ideas That Have Influenced Civilization IN THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS Translated and Arranged in Chronological or Historical Order, so that Eoglish Students may read at First Hand for Themselves OLIVER J. THATCHER, Ph. D. Dcparfmmt of Hisfory, University of Chicago, Editor in Chid Assisted by mme than 125 University Yen, Specialists in their own fields AN OPINION I have purchased and examined the Documents of the ORIGINAL RESEARCH LIBRARY edited by Dr. Thatcher and am at once impressed with the work as an ex- ceedingly valuable publication, unique in kind and comprehensive in scope. ./ It must prove an acquisition to any library. ‘THOMAS JONATHAN BURRILL. Ph.D., LL.D., V&e-Pres. of the University of NZinois. This compilation is uniquely valuable for the accessi- bility it gives to the sources of knowledge through the use of these widely gathered, concisely stated, con- veniently arranged, handsomely printed and illustrated, and thoroughly indexed Documents. GRAHAM TAYLOR, LL.D., Director of The Institute of Social Science at fhe Universify of Chicago. SEND POST CARD FOR TABLE OF CONTENTS UNIVERSITY RESEARCH EXTENSION AUDITORIUM BUILDING, CHICAGO TRIGGS MAGAZINE A MAGAZIiVE OF THE NEW ORDER IN STATE, FAMILY AND SCHOOL Editor, _ OSCAR LOVELL TRIGGS Associates MABEL MACCOY IRWIN LEON ELBERT LANDONE ‘rHIS Magazine was founded to represent the New Spirit in literature, education and social reform. -

View 2019 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 Front Court, engraved by R B Harraden, 1824 VOL CI MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 The Master, Dame Fiona Reynolds, in the new portrait by Alastair Adams May Ball poster 1980 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2018–2019 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2020. News about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/members/keepintouch. College enquiries should be sent to [email protected] or addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. General correspondence concerning the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. Correspondence relating to obituaries should be addressed to the Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, with a special nod to the unstinting assistance of the College Archivist. -

Download File (Pdf)

2021 FORUM REPORT COVID-19 in Africa one year on: Impact and Prospects MO IBRAHIM FOUNDATION 2021 FORUM REPORT COVID-19 in Africa one year on: Impact and Prospects MO IBRAHIM FOUNDATION Foreword by Mo Ibrahim Notwithstanding these measures, on current projections Founder and Chair of the Mo Ibrahim Africa might not be adequately covered before 2023. Foundation (MIF) Vaccinating Africa is an urgent matter of global security and all the generous commitments made by Africa’s partners must now be delivered. Looking ahead - and inevitably there will be future pandemics - Africa needs to significantly enhance its Over a year ago, the emergence and the spread of COVID-19 homegrown vaccine manufacturing capacity. shook the world and changed life as we knew it. Planes were Africa’s progress towards its development agendas was off grounded, borders were closed, cities were shut down and course even before COVID-19 hit and recent events have people were told to stay at home. Other regions were hit created new setbacks for human development. With very earlier and harder, but Africa has not been spared from the limited access to remote learning, Africa’s youth missed out pandemic and its impact. on seven months of schooling. Women and girls especially The 2021 Ibrahim Forum Report provides a comprehensive are facing increased vulnerabilities, including rising gender- analysis of this impact from the perspectives of health, based violence. society, politics, and economics. Informed by the latest data, The strong economic and social impacts of the pandemic it sets out the challenges exposed by the pandemic and the are likely to create new triggers for instability and insecurity. -

Download Our Exhibition Catalogue

CONTENTS Published to accompany the exhibition at Foreword 04 Two Temple Place, London Dodo, by Gillian Clarke 06 31st january – 27th april 2014 Exhibition curated by Nicholas Thomas Discoveries: Art, Science & Exploration, by Nicholas Thomas 08 and Martin Caiger-Smith, with Lydia Hamlett Published in 2014 by Two Temple Place Kettle’s Yard: 2 Temple Place, Art and Life 18 London wc2r 3bd Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Copyright © Two Temple Place Encountering Objects, Encountering People 24 A catalogue record for this publication Museum of Classical Archaeology: is available from the British Library Physical Copies, Metaphysical Discoveries 30 isbn 978-0-9570628-3-2 Museum of Zoology: Designed and produced by NA Creative Discovering Diversity 36 www.na-creative.co.uk The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences: Cover Image: Detail of System According to the Holy Scriptures, Muggletonian print, Discovering the Earth 52 plate 7. Drawn by Isaac Frost. Printed in oil colours by George Baxter Engraved by Clubb & Son. Whipple Museum of the History of Science, The Fitzwilliam Museum: University of Cambridge. A Remarkable Repository 58 Inside Front/Back Cover: Detail of Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Komei bijin mitate The Polar Museum: Choshingura junimai tsuzuki (The Choshingura drama Exploration into Science 64 parodied by famous beauties: A set of twelve prints). The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge. Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Thinking about Discoveries 70 Object List 78 Two Temple Place 84 Acknowledgements 86 Cambridge Museums Map 87 FOREWORD Over eight centuries, the University of Cambridge has been a which were vital to the formation of modern understandings powerhouse of learning, invention, exploration and discovery of nature and natural history. -

TTP-Wedding-Brochure.Pdf

Weddings Contents 01 About Two Temple Place 02 Lower Gallery 03 Great Hall 04 Library 05 Upper Gallery 06 Capacities & Floorplans 07 Our Suppliers 08 Information 09 Contact Us 01 About Two Temple Place Exclusively yours for the most memorable day of your life. Two Temple Place is a hidden gem of Victorian architecture and design, and one of London’s best-kept secrets. Commissioned by William Waldorf Astor for his London office and pied-a-terre in 1895, this fully-licensed, riverside mansion is now one of London’s most intriguing and elegant wedding venues. Say `I do’ in one of our three licensed ceremony rooms and enjoy every aspect of your big day, from ceremony to wedding breakfast and dancing all under one roof. Sip champagne in Astor’s private Library; surprise your guests with a journey through our secret door; dine in splendour in the majestic Great Hall or dance the night away in the grand Lower Gallery. With a beautiful garden forecourt which acts as a suntrap in the summer months for celebratory drinks and canapés, whatever the time of year Two Temple Place is endlessly flexible and packed with individual charm and character. Let our dedicated Events team and our experienced approved suppliers guide you through every aspect of the planning process, ensuring an unforgettable day for you and your guests. All funds generated from the hire of Two Temple Place support the philanthropic mission of The Bulldog Trust, registered charity 1123081. 02 Lower Gallery Walk down the aisle in the Lower Gallery with its high ceilings and stunning wood panelling as sunlight streams through the large ornate windows. -

2019/20 Exhibitions

2020/21 EXHIBITIONS (list updated on 25 February) National Gallery, London Young Bomberg and the Old Masters (until 1 March) (Free) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/young-bomberg-and-the-old-masters Nicolaes Maes: Dutch Master of the Golden Age (until 31 May) (Free) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/nicolaes-maes-dutch-master-of-the-golden-age Titian: Love, Desire, Death (16 March – 14 June) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/titian-love-desire-death Artemisia Gentileschi (4 April – 26 July) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/artemisia Sin (15 April – 5 July) (Free) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/sin Raphael (3 October – 24 January 2021) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/the-credit-suisse-exhibition-raphael Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist (13 February 2021 – 16 May 2021) https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/durers-journeys-travels-of-a-renaissance-artist National Portrait Gallery, London (will be closed from June 2020 for three years for revamp!) Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things (12 March – 7 June) https://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions/2019/cecil-beatons-bright-young-things/ David Hockney: Drawing from Life (27 February – 28 June) https://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/exhibitions/2019/david-hockney-drawing-from-life/ BP Portrait Award (21 May – 28 June) https://www.npg.org.uk/whatson/bp-portrait-award-2020/exhibition/ Royal Academy Picasso and Paper (until 13 April) https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibition/picasso-and-paper Léon -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

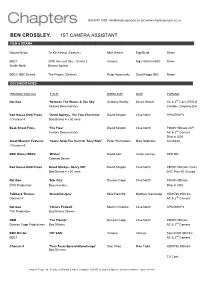

Ben Crossley. 1St Camera Assistant

020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk ! 020 8747 1203 | [email protected] | www.chapterspeople.co.uk ! BEN CROSSLEY. 1ST CAMERA ASSISTANT FILM & DRAMA Natural Nylon ‘To Kill A King’ (Feature) Mike Barker Eigil Bryld 35mm BBC1 ‘2000 Acres of Sky’ - Series 2 Various Nigel Walters BSC 16mm Zenith North (Drama Series) BBC1/ BBC Drama ‘The Project’ (Drama) Peter Kosminsky David Higgs BSC 16mm DOCUMENTARIES PRODUCTION CO. TITLE DIRECTOR DOP FORMAT Nat Geo ‘Between The Waves & The Sky’ Anthony Wonke Simon Niblett AC & 2nd Cam, RED MX, Feature Documentary Cineflex. Ongoing-Qata Red House DOX Prods ‘David Starkys- The Two Churchills’ David Sington Clive North HPX3700 P2 / Channel 4 Doc/Drama 4 x 50 mins Beak Street Films ‘The Flaw’ David Sington Clive North F900R HDCam 24P Feature Documentary AC & 2nd Camera Shot in USA Great Western Features ‘Comic Strip-The Hunt for Tony Blair’ Peter Richardson Mike Robinson Arri Alexa / Channel 4 BBC Wales/ BBC2 ‘Whites’ David Kerr Jamie Cairney RED MX Comedy Series Red House DOX Prods David Starkys- Henry VIII' David Sington Clive North F900R HDCam/ Varicam Doc/Drama 4 x 50 mins DVC Pro HD. Europe Nat Geo ‘Star City’ Duncan Copp Clive North F900R HDCam DOX Production Documentary Shot in USA Talkback Thames ‘Grand Designs’ Mike Ratcliffe Matthew Gammage HDW790 HDCam Channel 4 AC & 2nd Camera Nat Geo ‘Christs Fireball’ Martin O’Collins Clive North HPX3700 P2 TV6 Production Doc/Drama 50mins HBO ‘The Planets’ Duncan Copp Clive North F900R HDCam Duncan Copp Productions Doc 50mins AC & 2nd Camera BBC Bristol ‘DIY SOS’ Various Various Sony F800 XDCam BBC1 AC & 2nd Camera Channel 4 ‘Time Team Special-Stonehenge’ Sian Price Mike Todd HDW790 HDCam Doc 50 mins CV Cont…… Chapters People Ltd. -

E/2021/NGO/XX Economic and Social Council

United Nations E/2021/NGO/XX Economic and Social Distr.: General July 2021 Council Original: English and French 2021 session 13 July 2021 – 16 July 2021 Agenda item 5 ECOSOC High-level Segment Statement submitted by organizations in consultative status with the Economic and Social Council * The Secretary-General has received the following statements, which are being circulated in accordance with paragraphs 30 and 31 of Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. Table of Contents1 1. Abshar Atefeha Charity Institute, Chant du Guépard dans le Désert, Charitable Institute for Protecting Social Victims, The, Disability Association of Tavana, Ertegha Keyfiat Zendegi Iranian Charitable Institute, Iranian Thalassemia Society, Family Health Association of Iran, Iran Autism Association, Jameh Ehyagaran Teb Sonnati Va Salamat Iranian, Maryam Ghasemi Educational Charity Institute, Network of Women's Non-governmental Organizations in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Organization for Defending Victims of Violence,Peivande Gole Narges Organization, Rahbord Peimayesh Research & Educational Services Cooperative, Society for Protection of Street & Working Children, Society of Iranian Women Advocating Sustainable Development of Environment, The Association of Citizens Civil Rights Protection "Manshour-e Parseh" 2. ACT Alliance-Action by Churches Together, Anglican Consultative Council, Commission of the Churches on International Affairs of the World Council of Churches, Lutheran World Federation, Presbyterian Church (USA), United Methodist Church - General Board of Church and Society 3. Adolescent Health and Information Projects, European Health Psychology Society, Institute for Multicultural Counseling and Education Services, Inc., International Committee For Peace And Reconciliation, International Council of Psychologists, International Federation of Business * The present statements are issued without formal editing. -

2018 Annual Report

2A018 nnual Report Details Trustees, staff and volunteers The William Morris Society PRESIDENT WMS VOLUNTEER ROLES Registered address: Jan Marsh (to 12 May 2018) Journal Editor: Owen Holland Kelmscott House Lord Sawyer of Darlington (from 12 May 2018) Magazine Editor: Susan Warlow 26 Upper Mall Librarian: Penny Lyndon Hammersmith TRUSTEES Journal Proofreader: Lauren McElroy London W6 9TA Martin Stott, Chair (to 12 May 2018) Stephen Bradley, Chair (from 12 May 2018) The William Morris Society is extremely Tel: 020 8741 3735 Rebecca Estrada-Pintel, Vice Chair fortunate to be able to draw on a wide range Email: [email protected] Andrew Gray, Treasurer of expertise and experience from our www.williammorrissociety.org Natalia Martynenko-Hunt, Secretary volunteers, who contribute many hundreds of Philip Boot (from 12 May 2018) hours of their time to help with welcoming TheWilliamMorrisSociety Jane Cohen visitors to the museum, delivering education @WmMorrisSocUK Serena Dyer (to 12 May 2018) sessions to schools and families, giving printing williammorrissocietyuk Michael Hall demonstrations, answering enquiries, Kathy Haslam (to 12 May 2018) cataloguing and caring for our collections, Registered Charity number 1159382 Jane Ibbunson (from 12 May 2018) office administration, serving refreshments and Fiona Rose maintaining our garden. John Stirling (from 12 May 2018) We are grateful to all who give up their time The Trustee Board operates through five to help with the work of the Society. committees. These are: Finance and General -

United Nations Private Sector Forum on the Millennium Development Goals

MEETING REPORT UNITED NATIONS PRIVATE SECTOR FORum on the Millennium Development Goals 22 SEPTEMBER 2010, NEW YORK 2 UN Private Sector Forum Organizing Committee Members: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Fund for Agricultural Develop- ment (IFAD), International Labour Organization (ILO), Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM, part of UN Women), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), United Nations Foundation (UNF), United Nations Global Compact Office, United Nations Office for Partnerships (UNOP), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), World Bank, World Food Programme (WFP). Photos: © UN Global Compact/Michael Dames 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 Commitments to Development 8 2010 Commitments 8 Tracking 2008 Commitments 9 Welcome and Opening Addresses 12 Luncheon Keynote Remarks 15 Thematic Discussions – Advancing Solutions through Business Innovation 16 Poverty and Hunger 18 Maternal and Child Health and HIV/AIDS 20 Access to Education through Innovative Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) 22 Innovations for Financial Inclusion 24 Empowering Women and Achieving Equality 26 Green Economy 28 Closing Addresses 30 Appendices 31 Accelerating Private Sector Action to Help Close MDG Gaps – Key Messages 31 Bilateral Donors’ Statement in Support of Private Sector Partnerships for Development 33 Agenda 35 Participant List 39 4 “ An investment in the MDGs is an investment in growth, prosperity and the markets of the future — a win-win proposition.” – H.E. -

E/ECA/CM/53/5 Economic and Social Council

United Nations E/ECA/CM/53/5 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 1 April 2021 Original: English Economic Commission for Africa Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development Fifty-third session Addis Ababa (hybrid), 22 and 23 March 2021 Report of the Conference of Ministers on the work of its fifty-third session Introduction 1. The fifty-third session of the Economic Commission for Africa Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development was held at the Economic Commission for Africa in Addis Ababa, in a hybrid format featuring both in-person and online participation, on 22 and 23 March 2021. I. Opening of the session [agenda item 1] A. Attendance 2. The meeting was attended by representatives of the following States: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia , Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe. 3. The following United Nations bodies and specialized agencies were represented: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; International Civil Aviation Organization; International Fund for Agricultural Development; International Labour Organization; International Organization