Southern Sudan – 2004 Action Against Hunger–USA (ACF-USA) 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Christs of the Black Christs of by J. Penn De

The Black Christs of Africa A Bible of Poems By J. Penn de Ngong Above all, I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. Wilfred Owen, British Poet Poem 22 petition for partition We, the auto-government of the Republic of Ruralia, Voicing the will of the democratic public of Ruralia, Are writing to your Theocratic Union of Urbania. Our grievances are on the following discontentment: Firstly, your purely autocratic Government of Urbania, Has solely dishonoured and condemned the document That we all signed – and codenamed – “Bible of Peace”. You’ve violated its gospel, the cause of our fatal disagreement; Wealth: You’re feeding our autonomous nation with ration apiece. In your annual tour, compare our city – Metropollutant – of Ruralia With its posh sister city of Urbania, proudly dubbed Metropolitania. All our resources, on our watching, are consumed up in Urbania. Our intellectuals and workforce are abundant but redundant. Henceforth, right here, we demarcate to be independent! You are busy strategizing to turn Ruralia into Somalia: Yourselves landlords, creating warlords, tribal militia, And bribing our politicians to speak out your voice, And turning our villages into large ghettos of slum, And our own towns into large cities of Islam. With these experiences, we’ve no choice, But t’ ask, demand, fight... for our voice. They oft’ say the end justifies the means, We, Ruralians, must reform all our ruins; The first option: thru the ballot, Last action: bullet! J. Penn de Ngong (John Ngong Alwong Alith as known in his family) came into this world on a day nobody knows. -

Education in Emergencies, Food Security and Livelihoods And

D e c e m b e r 2 0 1 5 Needs Assessment Report Education in Emergencies, Food Security, Livelihoods & Protection Fangak County, Jonglei State, South Sudan Finn Church Aid By Finn Church Aid South Sudan Country Program P.O. Box 432, Juba Nabari Area, Bilpham Road, Juba, South Sudan www.finnchurchaid.fi In conjunction with Ideal Capacity Development Consulting Limited P.O Box 54497-00200, Kenbanco House, Moi Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected], [email protected] www.idealcapacitydevelopment.org 30th November to 10th December 2015 i Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... VII 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 FOOD SECURITY AND LIVELIHOOD, EDUCATION AND PROTECTION CONTEXT IN SOUTH SUDAN ............................... 1 1.2 ABOUT FIN CHURCH AID (FCA) ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT IN FANGAK COUNTY .................................................................................................. 2 1.4 PURPOSE, OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................... -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

South Sudan IDSR Bulletin

South Sudan Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) Epidemiological Update W11 2018 (Mar 12 - Mar 18) Major Epidemiological Developments W11 2018 • Completeness for IDSR reporting at county level was 70% . Completeness for EWARS reporting from IDP sites was 81% ________________________________________________________________________ • A total of 13 alerts were reported, of which 62% have been verified. 0 alerts were risK assessed and 0 required a response. ________________________________________________________________________ • Rift Valley Fever outbreaK - Yirol East with 40 suspect human cases including 6 confirmed; 3 probable; 19 non-cases; and 12 pending classification. Nine confirmed animal cases (cattle). _________________________________________________________________________ • Following the confirmation of a measles outbreaK in Aweil East [after four measles IgM positive cases were confirmed on 24 Feb 2018], a reactive measles campaign planned targeting children 6 months to 59 months. The campaign is slated for March 26-31, 2018. _________________________________________________________________________ • In Torit, suspect meningitis continued to decline with the weeKly attacK rate remaining below the alert threshold during weeKs 11 & 12. At least 173 suspect cases including 31 deaths have been reported. During the weeK, CSF samples arrived in Paris for testing. _____________________________________________________________________________2 Surveillance| IDSR surveillance indicators • Completeness for IDSR reporting -

1 Covid-19 Weekly Situation

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH (MOH) PUBLIC HEALTHPUBLIC EMERGENCY HEALTH EMERGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATIONS CENTRE (PHEOC) CENTRE (PHEOC) COVID-19 WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Issue NO: 33 Reporting Period: 12-18 October 2020 (week 42) 36,740 2,655 CUMULATIVE SAMPLES TESTED CUMULATIVE RECOVERIES 2,847 CUMULATIVE CONFIRMED CASES 55 9,152 CUMULATIVE DEATHS CUMULATIVE CONTACTS LISTED FOR FOLLOW UP 1. KEY HIGHLIGHTS A cumulative total of 2,847 cases have been confirmed and 55 deaths have been recorded, with case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.9 percent including 196 imported cases as of 18 October 2020. 1 case is currently isolated in health facilities in the Country; and the National IDU has 99% percent bed occupancy available. 2,655 cases (0 new) have been discharged to date. 135 Health Care Workers have been infected since the beginning of the outbreak, with one death. 9,152cumulative contacts have been registered, of which 8,835 have completed the 14-day quarantine. Currently, 317 contacts are being followed, of these 92.1 percent (n=292) contacts were reached. 722 contacts have converted to cases to date; accounting for 25.3 percent of all confirmed cases. Cumulatively 36,740 laboratory tests have been performed with 7.7 percent positivity rate. There is cumulative total of 1,373 alerts of which 86.5 percent (n=1, 187) have been verified and sampled; Most alerts have come from Central Equatorial State (75.1 percent), Eastern Equatoria State (4.4 percent); Upper Nile State (3.2 percent) and the remaining 17.3 percent are from the other States and Administrative Areas. -

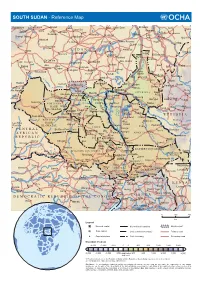

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map Kebkabiya El Fashir Abyad Bara Umm Dam El Kawa Ermil Nahl Doka Umm Bel Sennar Tawila Dirra Umm El Hilla Iyal Es Suki El Hawata Keddada Mahbub El Obeid Rabak Jebel Shangil Tobay Wad Banda Dud Singa Gallabat Wada`ah Umm Rawaba En Nahud El Rahad Higar Galegu El Jebelein Kas Taweisha S U D A N El Abbasiya Nyala Dilling Kortala Dangur El Odaiya Geigar Sharafa Delami Ed Damazin Rashad Renk e l El Barun Ed Da`ein i El Lagowa Abu Jibaiha Edd El Fursan N Babanusa e Heiban t Abu Abu i Bau Guba Ragag h Matariq Kulshabi Bikori Gabra W El Muglad Kadugli Kologi Keili Mumallah Umm Ulu Buram Keilak Talodi Barbit Wadega Belfodiyo Qardud Kaka Paloich Tungaru Junguls Asosa Radom Riangnom Sumeih El Melemm Oriny Kodok Mendi Boing Bambesi Hofrat Naam Fagwir Aboke en Nahas Malakal Nejo Abyei UPPER NILE Daga Bentiu Gimbi Bai War-awar Fangak Malwal Post Kafia Pan Nyal Mayom Kingi Malualkon Abwong Wang Kai Fagwir Kan Sobat Banyjiel Gidami Sadi Aweil Wun Rog Yubdo Gossinga UNITY Gumbiel Nasser NORTHERN Gogrial Nyerol Malek Thul Raga BAHR Akop Leer Mogogh Biel Bure Metu Wun Gambela EL GHAZAL WARRAP Ayod Waat Abay Gore Kwajok Shwai Adok Atiedo Warrap Fathai Faddoi Jonglei Canal Tor Deim Zubeir Madeir E T H I O P I A Bisellia Bir Di Duk Fadiat Akobo WESTERN Wau Gech`a Lol Mbili Duk Kongettit Les Trois BAHR Wakela Atum Faiwil Tepi Riviêres EL GHAZAL Tonj Shambe Peper Pochalla LAKES Kongor C E N T R A L Bo River Post Rafili Giamciar Teferi Rumbek Lau Akelo Palwal Jonglei JONGLEI Pibor A F R I C A N Ubori Akot Pibor Yirol Kantiere R E P U -

Aweil East County Executive Summary June 08 VF

South Sudan Preliminary Results Nutritional anthropometric and retrospective mortality surveys Children aged 6 – 59 months Aweil East County Northern Bahr El Ghazal State SOUTH SUDAN 13 th – 28 th of June 2008 Funded by: Common Humanitarian Fund (CHF) Transport Support: World Food Program (WFP) 2 INTRODUCTION Aweil East County is situated in Northern Bahr El Ghazal (NBeG) state, in Southern Sudan. It is under the Government of Southern Sudan, following the peace agreement signed in January 2005 between the government of Khartoum and the SPLM (Sudanese People Liberation Movement). NBeG is one of the smaller states of Southern Sudan but the most densely populated. It is a returnee/IDP entry point from Khartoum and Darfur. More than 40,000 returnees and 8,000 IDPs - including 27,000 returnees and 4,000 IDPs in Aweil East County 1- are reported to have arrived during the first half of 2008 alone. In 2007, 70,000 returnees were registered to have arrived in Northern Bahr el Ghazal State 2 . Aweil East County is inhabited by the Dinka ethnic group. It is composed of seven administrative payams, and each run from the north to the south, resulting in long and narrow areas. They are: Malualbai, Baac, Madhol, Mangartong, Mangok and Wunlang payams. In the rainy season, between April and September, roads are practically or completely impassable, especially in the lowlands. In January 2008, ACF-F3 took over Tearfund nutrition program in Aweil East County by keeping the Tearfund OTP 4 sites, opening a TFC 5 in Malualkon and conducting nutritional surveys. Nutritional and retrospective mortality surveys are undertaken every six months in order to estimate the malnutrition and the mortality rates. -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #2, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 December 7, 2018

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 DECEMBER 7, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Relief actor records at least 150 GBV cases in Bentiu during a 12-day period 5% 7% 20% UN records two aid worker deaths, 60 7 million 7% Estimated People in South humanitarian access incidents in October 10% Sudan Requiring Humanitarian USAID/FFP partner reaches 2.3 million Assistance 19% 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan – people with assistance in October December 2017 15% 17% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE 6.1 million Health (17%) Nutrition (15%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/FFP $402,253,743 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) September 2018 Shelter & Settlements (5%) 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $628,994,9784 2 million BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 Estimated IDPs in 84% 9% 5% South Sudan OCHA – November 8, 2018 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,760,121,951 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES 194,900 Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases KEY DEVELOPMENTS UNMISS – November 15, 2018 During a 12-day period in late November, non-governmental organization (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) recorded at least 150 gender-based violence (GBV) cases in Unity State’s Bentiu town, representing a significant increase from the approximately 2.2 million 100 GBV cases that MSF recorded in Bentiu between January and October. -

Humanitarian Response Plan South Sudan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

Interethnic Conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging Ethnic Hatred Between the Lou Nuer and the Murle

Interethnic conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging ethnic hatred between the Lou Nuer and the Murle Yuki Yoshida* Abstract This article analyses the escalation of interethnic confl icts between the Lou Nuer and the Murle in Jonglei State of South Sudan. Historically, interethnic confl icts in Jonglei were best described as environmental confl icts, in which multiple ethnic groups competed over scarce resources for cattle grazing. Cattle raiding was commonly committed. The global climate change exacerbated resource scarcity, which contributed to intensifying the confl icts and developing ethnic cleavage. The type of confl ict drastically shifted from resource-driven to identity-driven confl ict after the 2005 government-led civilian disarmament, which increased the existing security dilemma. In the recent confl icts, there have been clear demonstrations of ethnic hatred in both sides, and arguably the tactics used amounted to acts of genocide. The article ends with some implications drawn from the Jonglei case on post-confl ict reform of the security sector and management of multiple identities. * Yuki Yoshida is a graduate student studying peacebuilding and conflict resolution at the Center for Global Affairs, New York University. His research interests include UN peacekeeping, post-conflict peacebuilding, democratic governance, humanitarian intervention, and the responsibility to protect. He obtained his BA in Liberal Arts from Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, CA, in 2012. 39 Yuki Yoshida Introduction After decades of civil war, the Republic of South Sudan achieved independence in July 2011 and was recognised as the newest state by the international community. However, South Sudan has been plagued by the unresolved territorial dispute over the Abyei region with northern Sudan, to which the world has paid much attention. -

Viable Support to Transition and Stability (Vistas) Fy 2016 Annual Report October1, 2015 - September 30, 2016

VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) FY 2016 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER1, 2015 - SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 JUNE 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by AECOM. VIABLE SUPPORT TO TRANSITION AND STABILITY (VISTAS) FY 2016 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2015- SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 Contract No. AID-668-C-13-00004 Submitted to: USAID South Sudan Prepared by: AECOM International Development Prepared for: Office of Transition and Conflict Mitigation (OTCM) USAID South Sudan Mission American Embassy Juba, South Sudan DISCLAIMER: The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FY 2016 Annual Report/ Viable Support to Transition and Stability (VISTAS) i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 II. Political and security Landscape ............................................................................................ 2 National Political, Security, and Operational Landscape ........................................................................... 2 Political & Security Landscape in VISTAS Regional Offices ...................................................................... 4 III. Program Strategy.................................................................................................................... 7 IV. Program Highlights -

Tables from the 5Th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008

Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 CENSU OR S,S F TA RE T T IS N T E IC C S N A N A 123 D D β U E S V A N L R ∑σ µ U E A H T T I O U N O S S S C C S E Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 ii Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... x Foreword ....................................................................................................................... xiv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ xv Background and Mandate of the Southern Sudan Centre for Census, Statistics and Evaluation (SSCCSE) ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 History of Census-taking in Southern Sudan....................................................................... 2 Questionnaire Content, Sampling and Methodology ............................................................ 2 Implementation .............................................................................................................. 2